“Be your own artist, and always be confident in what you’re doing. If you’re not going to be confident, you might as well not be doing it.” —Aretha Franklin

Many, if not most, musicians I know suffer from something I call music dysmorphia. As people who suffer from body dysmorphic disorder torture themselves with an overwhelming preoccupation of their perceived flaws, be they real or imaginary, musicians often listen back to their musical performances and only hear what they don’t like. (Timing is rushed, tone’s too thin or too bassy, note choice too cliché or too weird; it’s never quite right to their ears). I know a ton of players who are way better musicians than I will ever be, yet they genuinely don’t like the way they play. It’s not false modesty, it’s the inability to process reality accurately.

I see it come up often during Rig Rundowns. Usually, players begin the interview by playing a 15- to 45-second improvised introduction. Often, they’ll be playing, it all sounds great, then they hit something they don’t really like. They get a frustrated look on their face and ask to take it again. But now they are in their heads. The second take usually feels a bit self-conscious, not as free and flowing as the first take. You can almost hear their thoughts: “This will be online forever, evidence of my poor playing.” You rarely hear a second take that has the magic of the first one because they’re thinking about being judged.

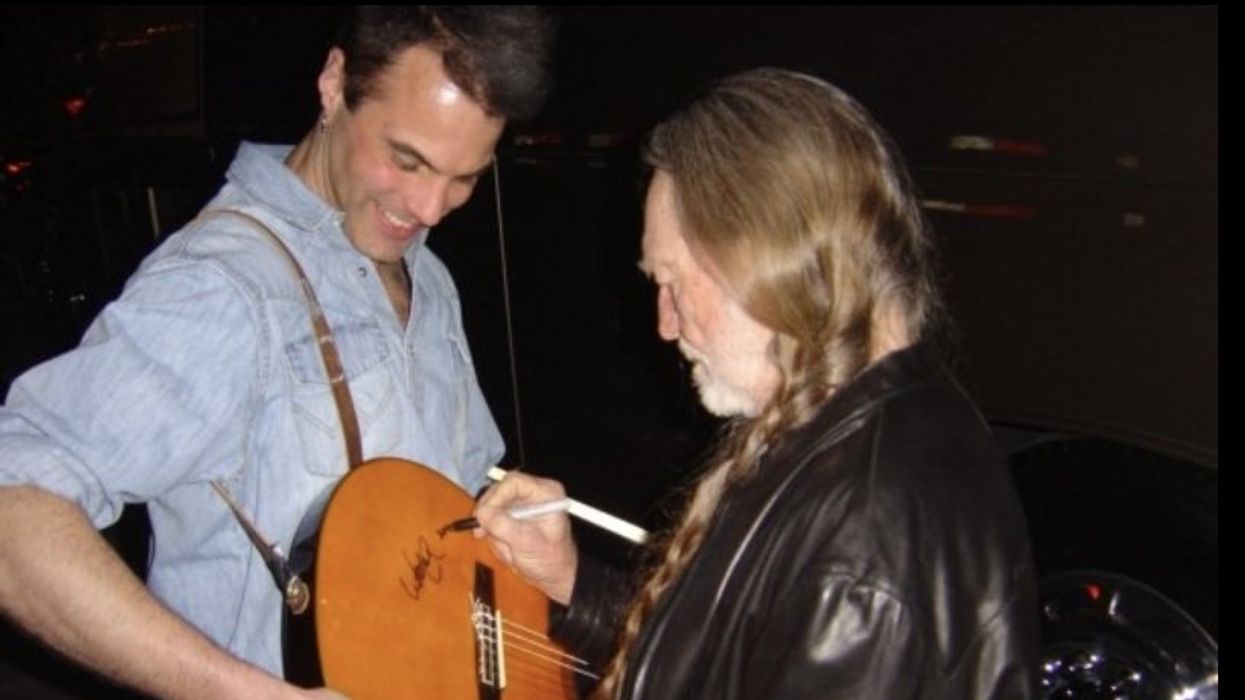

The author with one of Nashville’s finest, Tom Bukovac.

Photo by Chris Kies

I know there’s a disparity between the music that I hear in my head when I’m playing and the music I’m actually playing. I often phone-record songs on my gig to gather some evidence of what I actually sound like: check the tone, timing, note choice. There are gigs where I feel ashamed of what’s coming out of my amp, but when I listen back, it’s fine, sometimes even good. Other times, I think I’m killing it, but when I hear the recording, I feel a crushing pain of disappointment combined with deep shame.

I suspect we all sound the best when nobody is listening. When you have an audience, then you judge yourself because you think you are being judged. Why should we care? Music is not a contest, it’s art.

“People respond to reckless abandon in art.”

There is no agreed definition of what constitutes art. Art is subjective. There are no wrong decisions with art, so we should be cool with whatever we play. Sadly, that’s not the case. I suspect that’s because music means so much to us. Playing music is not just something we do, it’s who we are. When I was younger, I worked a wide variety of jobs, but I never felt bad about being a terrible roofer, waiter, factory worker, or teacher, because this was just something I had to do for money—it was not my life’s goal. But being a musician is not only my passion and my job, it is how I am wired. Music is my identity. So when I play and it sounds like I can’t play, my sense of self is called into question: What am I doing with my life? Who am I? Performing for others means putting our tiny, naked heart in our hands, and offering it to God and everybody to be judged. That’s a scary, vulnerable position.

I was jamming with Austin Mercuri, a great bass-player buddy of mine, and I asked him if he thinks music dysmorphia is a thing. He agreed that it totally is a thing, and he gave an interesting insight. Austin said, “Ever notice when you record something comedic, like a parody, it turns out so great musically? Because it’s tongue-in-cheek, any mistakes or oversteps just make it better, so you go for stuff beyond what you’ve done before, take crazy chances fearlessly, and they work.” That’s the trick: Don’t care, then you can explore without any second guessing or fear of judgment, because you’re just goofing off. People respond to reckless abandon in art.

As a musician, you’re probably not going to find happiness by comparing your playing to others, which is pretty much impossible. For example, my friend Tom Bukovac and I moved to Nashville around the same time. I’ve watched his career take off and felt the sting of envy for years. But now, I listen to Buk play and the only thing I feel is inspiration and awe. With innate talent and an obsessive work ethic, Buk developed this ability to tap into music, where it flows through him, unhindered by doubt or self-consciousness. Why should Buk’s brilliance, or anybody else’s, make me feel bad about my thing? Get back to why you started playing in the first place. Stop thinking, just play.