As we gather ’round the fire and stare at the ashes of what used to be the record business, I’m reminded of Nick Hornby’s 1995 novel (and later, movie) High Fidelity. In one iconic speech straight from the book, John Cusack says: “But the most important thing is … what you like, not what you’re like. Books, records, films—these things matter. Call me shallow, it’s the fuckin’ truth.”

Commercial record stores first appeared in the 1920s, but mass marketing did not kick in until 1948, when Columbia invented the 33 1/3 rpm long-playing (LP) record, and 1949, when RCA countered with the 45 rpm single.

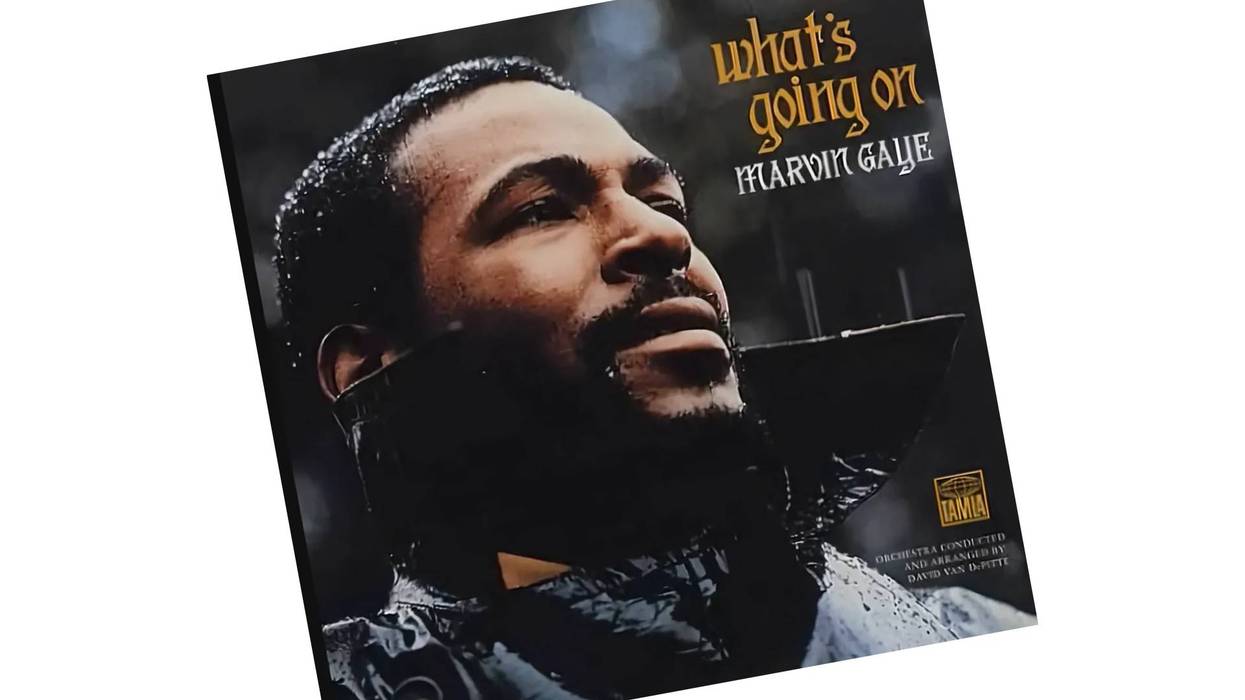

In the mid 1950s, rock ’n’ roll exploded with Elvis, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard, and records were everywhere. By the time I came along in the ’60s and ’70s, even in remote Montana, our grocery store, pharmacy, and gas station all had a record section. There were also several dedicated record stores around town where you could hang out, listen to music, and occasionally buy records, black light posters, rock ’n’ roll t-shirts, and even a bong, if you wanted. By 1999, global recorded-music revenue crested at roughly $40 billion, with CDs costing a stiff 18 bucks. We were buying the same albums we already owned on vinyl, just shinier. From the first commercial phonograph cylinders in the early 1900s to the absolute peak in 1999, the whole glorious scam ran 100 years; shorter than the Ottoman Empire, longer than MySpace. But not by much.

Then two things happened almost simultaneously: Shawn Fanning gave every dorm-room genius the power to copy anything, and Steve Jobs sold us the radical idea that maybe we didn’t need “Smells Like Teen Spirit” permanently welded to 12 other tracks. Napster lit the fuse; iTunes handed us the à la carte menu.

But the big bad record labels didn’t die. Rather, they molted. They stopped selling plastic and started renting you the same songs forever, ten bucks a month, please and thank you. Today, streaming constitutes 84 percent of U.S. recorded-music revenue. Your Spotify subscription gets carved up like a pizza: the platform keeps about 30 percent for servers and the like, the rights holders split the remaining 70 percent, and the label—owner of the master recording—walks away with roughly 55 percent of the total pool before the artist sees a dime. Same old middlemen, new religion.

Labels began to diversify like a hedge fund. Sync licensing is the golden ticket now—one 30-second needle-drop in a Netflix trailer can out-earn a billion streams. Performance royalties still trickle in every time your song plays in an Applebee’s. Weirdly, vinyl in 2024 finally outsold CDs in units. Labels press lavender-swirl limited editions for $300 a pop and the superfans line up like it’s 1973. The game isn’t dead; it just learned to stop relying on a single point of failure.

“One 30-second needle-drop in a Netflix trailer can out-earn a billion streams.”

Record labels today operate like venture capitalists: professional gamblers who bet other people’s money on startups that usually have no revenue, no profits, and a 70–90 percent chance of going to zero. The job is to find the one or two out of 100 that become Airbnb, Uber, or Jelly Roll. Write and record your songs, work social media, put money and time into promotion to get on playlists, play gigs, and, if you’re talented and lucky enough to stand out amongst the crowd of wannabes, a label will message you on Insta and maybe roll the dice on your project.

Will the major label disappear? Please. Labels survived Napster, survived the CD crash, survived having to pretend they like mumble rap, shoegaze, and Hillbilly Vanilli. They’ll just keep evolving into something that looks less like a record company and more like a private-equity firm. The next decade will be about superfans and algorithms. Exclusive fan clubs, direct-to-consumer box sets, virtual meet-and-greets where you pay 50 bucks to watch an artist unmute himself on Zoom—labels will own that if the indies don’t get there first. And AI? It’s already picking singles, buying ads, and probably writing half the choruses you hate but can’t stop humming.

Meanwhile the indies will keep carving out the weird corners—hyper-specific genres, local scenes, anything too prickly for the algorithmic blender. The pie is bigger, the slices are thinner, and nobody’s starving unless they’re lazy.

So yeah, the era of walking into Tower Records with a crumpled 20-dollar bill and walking out with physical proof you love something is deader than disco. But the labels? They just changed their wardrobe and learned to live on micro-transactions and attention.

For artists wanting to be stars, the music industry, like the rest of the world, has the mega rich, the struggling poor, and not a lot in the middle. But if you have talent and an instrument, you can always find a way to monetize it. You might survive by busking or living from a tip jar in a bar, but you will survive. Personally, if I have music and my basic needs met, I’m cool.