As a teen, I signed over my soul to the Columbia House mail-order mafia and bought the first few Led Zeppelin albums. I wore those albums out, dropping the needle in front of the “Heartbreaker” solo, “Black Dog,” and “Stairway” daily. Eventually I moved on to other obsessions and forgot how amazing this band was—until last night, when I watched Becoming Led Zeppelin, Bernard MacMahon’s 2025 documentary. The film, which earned a 10-minute ovation at the Venice Film Festival and grossed $13.2-million by May 2025, charts the explosive rise of Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham from their 1968 formation to 1970’s global dominance.

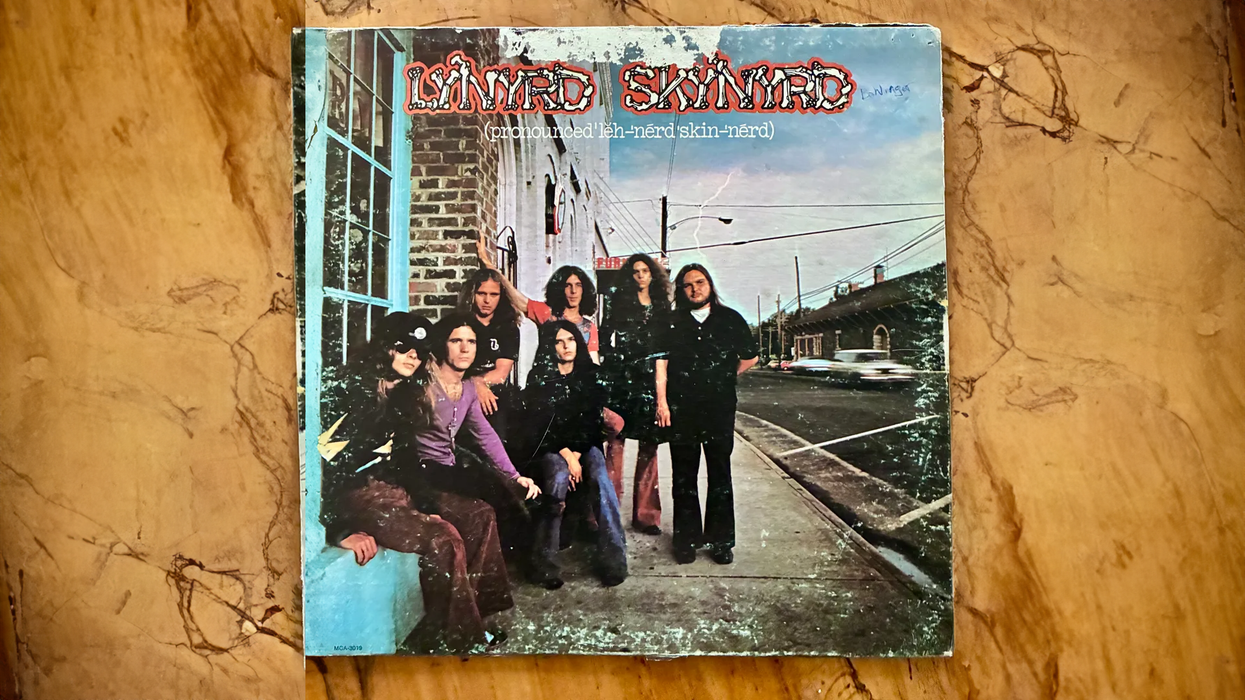

Although Page and Jones had worked together as session musicians, the first time the Zep lineup played music together was a jam in a tiny, rented rehearsal room in 1968. They tested their collective sound, starting with blues standards like “Train Kept A-Rollin’” and “Smokestack Lightning.” Forty-four days later, they were recording their first album, which they completed in 36 studio hours. This raw fusion of blues, rock, and psychedelic chaos, using a 4-track recorder and a shoestring budget of £1,800 (about $4,300, then), helped usher along a paradigm shift in music. Tracks like “Dazed and Confused” and “Good Times Bad Times” took wild risks, blending modal riffs, orchestral swells, and improvisational fire. Led Zeppelin was also incredibly diverse, with the heavy blues balanced by the acoustic “Black Mountain Side,” which was inspired by folk and Indian music. Zep II pushed further, from the primal riff of “Whole Lotta Love” to the semi-pastoral “Ramble On.” Page’s violin bow on guitar and Bonham’s heavier-than-heavy drumming defied norms, while Plant’s primal vocals careened between octaves.

Most of today’s modern music is polished to predictability, sterilized, and quantized. I bet that 99 percent of the sessions I’ve played on over the past two decades were all built on a grid with a stagnant click. Zep’s approach to tempos is more like classical music, where the tempo follows the emotion. “Dazed and Confused” starts with a slow, brooding tempo (around 60 to 70 bpm) driven by a descending bassline and Page’s eerie guitar. The middle section accelerates into a frenetic jam (around 120 to 140 bpm), with Bonham’s aggressive drumming and Page’s wild soloing, before slowing back down for the haunting violin-bow section and a final explosive ramp-up to 140 bpm. On “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You,” the transitions are so abrupt it feels like a car ran a red light and hit your passenger door. Zep would have been boring if they were constrained by a click.“If ‘Stairway to Heaven’ debuted today, would anybody hear it?”

Zeppelin’s tones and timbres also kept it unpredictable and endlessly interesting. Although John Paul Jones’ ’62 Jazz bass, Bonham’s Ludwig Super Classic, and Page’s guitars did most of the heavy lifting, Zep gave us vast sonic variety. Between the four members, they played 15 instruments on their first three albums and went to great lengths to make every song its own, unique sound. Yet, regardless of the instrumentation, Zeppelin always sounds like Zeppelin.

Rock ’n’ roll was built on experimentation and rebellion. It’s truly a DIY genre. So how did modern rock become so homogeneous and tame? Today’s unlimited digital tracks and AI tools (used in 60 percent of 2024’s Top 40, according to MusicTech.com) encourage overproduction, smoothing all quirks along the way. Radio and streaming exacerbate this as labels push 3-minute singles with hooks in 30 seconds to fit ad-heavy radio and prevent Spotify skips. Zeppelin’s era had FM stations playing 7-minute epics. Today, labels prioritize safe bets, favoring formulaic hits over risks. Social media and streaming reward conformity—songs must grab instantly, not unfold like a movie. If “Stairway to Heaven” debuted today, would anybody hear it?

By comparison, the 1960s were an incredibly open-minded time. Labels were looking for something to take a chance on because the outliers were paying off. The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and Hendrix successfully took chances, which enabled others like Zep to push the envelope farther, paving the way for yet more experimental artists like Bowie and Van Halen. The last boundary stretcher was probably Nirvana. That was 34 years ago.

There’s tons of amazing music being made today. But there’s also a whole lot of trend following rather than trend setting. Now that AI is writing/producing/creating music, that’s not going to diversify the mainstream. Becoming Led Zeppelin reminds us that music thrives on urgency and daring. Take chances.