Mastering Engineer Bob Ludwig of Gateway Mastering and DVD |

Outside of audiophiles and liner note junkies, your average music fan has paid little attention to mastering engineers and the important final process they’re involved with. Recently, however, people have noticed that recorded music is reproduced at much louder levels than ever before. Perhaps you’ve had your iPod on shuffle mode and noticed that newer songs are so loud that they can kill the overall vibe of what you’d prefer to be a steady, seamless presentation of your music stash. Legendary mastering engineer Bob Ludwig explained the trend at a South by Southwest presentation, breaking down the history of the problem, playing A/B’d comparisons for the audience and offering a glimmer of hope for music fans. Ludwig has mastered thousands of recordings in all genres. He’s worked with everyone from Led Zeppelin to Frank Sinatra. He’s the guy the Rolling Stones and Rush go to when they want their entire back catalogues remastered.

Ludwig breaks down the “Loudness Wars” at SXSW

Ludwig breaks down the “Loudness Wars” at SXSWBlame the A&R Guy

As Ludwig explains it, the loudness wars can be traced to A&R guys doing what they do best—whatever it takes to get their acts noticed. They started influencing their labels to pressure mastering engineers to make their acts’ cuts a little louder based on the idea that those songs would have more immediate appeal and attention-grabbing mojo when lost in a sea of other music. They envisioned radio station program directors sifting through piles of new music and industry-prepared compilations of music on the current charts and suddenly being wowed by their act’s song and its ability to stand out. Of course, this louder volume was also intended to have to same effect on listeners when unknowing disc jockeys would fire off the songs without adjusting the potentiometers on the board. Eventually, mastering engineers were making albums louder just to be able to keep up. Just like the musicians in your average band at a bar gig, someone’s attempt to bump their volume up to stand out results in someone else bumping their volume up just to be heard and before you know it, everything is way too loud.

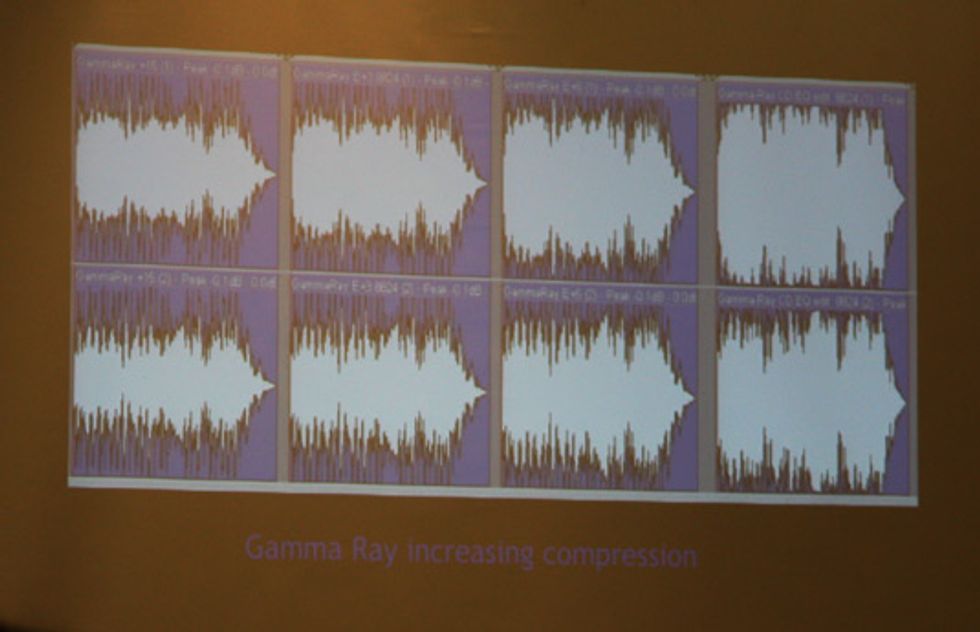

Among the many downsides of the creeping volume level on recordings is the fact that dynamic range has been lost. In order to master an album at a higher level, the difference between the peaks and the lows in a song’s waveform are basically eliminated. What should be a rich variety of levels that help a song develop character and have someplace to go ends up being double forte all the way through. This can be achieved via specific manipulation of various frequency ranges or simple compression.

A/Bing the Evidence

Ludwig’s presentation included the following two minute video clip by Matt Mayfield which demonstrates how this loud-for-loud’s sake process can turn a dynamic recording into a wimpy loud recording.

“We have a long to back off,” Ludwig told a room full of music industry types that included musicians, engineers and label execs. Ludwig played clips he was working on for a new Beck album that demonstrated where good dynamic levels should be at and where they’d have to be to follow the loudness trend. He also played clips of Gun N’ Roses’ Chinese Democracy, the long-anticipated album that is considered to be one of the most over-tweaked albums in history. When it was time for mastering, Axl Rose went to a number of mastering engineers and asked them to master the album. Rose picked Ludwig’s version in the end, to the surprise of everyone. Ludwig’s version is old-school—it isn’t overly artificially loud, over-compressed and squishy. It has dynamics and gives the album a chance to show its depth of emotion. However, it isn’t as dynamic as it could be. Ludwig’s mix backs off from the loudness trend but it is still louder than the records he used to make.

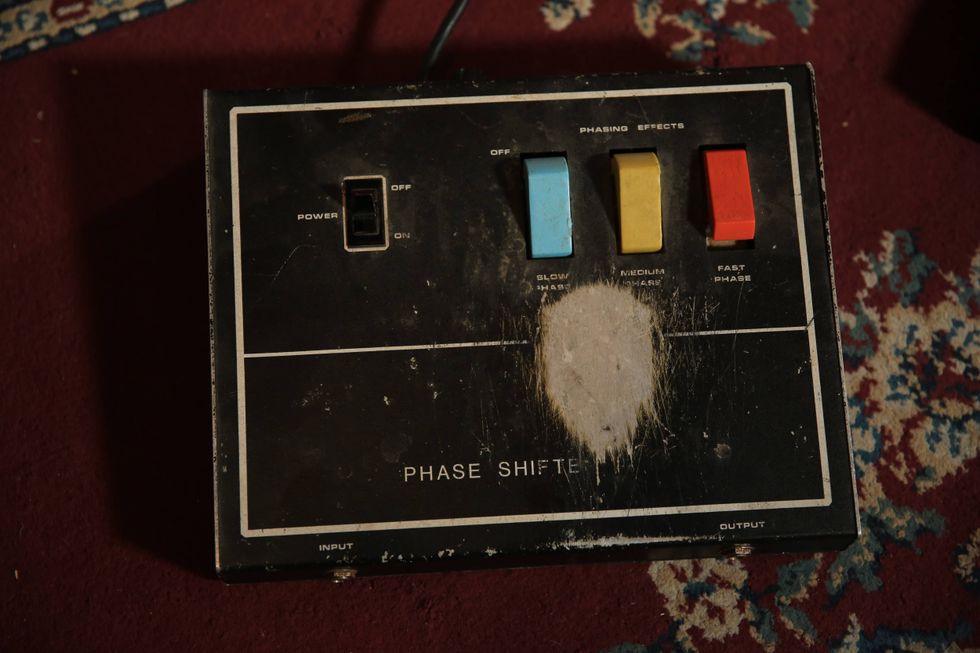

From left to right: original sound file and various versions with increased compression. Notice how the version on the far right, a mix that is typical for today’s loudness standards, is basically reduced to square waves.

The poster child of the loudness wars is Metallica’s Death Magnetic, the Rick Rubin-produced album that prompted 20,000 fans to petition for a remix. The fans actually got to A/B the album due to the release of remixed tracks produced for the Guitar Hero video game. They noticed that the Guitar Hero tracks weren’t over-compressed and let the band know they deserved better when buying CDs and downloading the album from the Internet.

To put the situation into perspective, Ludwig described the loudness wars from what he sees on his VU meters. “An average CD’s peaks are probably at +6dB to +6.5dB with the occasional 7dB peak," Ludwig said. "That Guns N’ Roses record [Chinese Democracy] averages +4dB. Death Magnetic is like +12dB or +13dB. The meter only goes up to +14dB.”

Good News

While acknowledging that the “forces that are out there are very strong forces,” Ludwig was pleased to report that the loudness wars may have peaked.

“Since this Death Magnetic record, I’ve actually for the first time in years had a couple of people ask me to redo something at a lower level with more dynamics,” Ludwig said. “…and that hasn’t happened to me in a long time. “ Ludwig mentioned Axl Rose’s take on the situation when they were working on Chinese Democracy: “I don’t have any issue with the radio stations paying attention to my record,” he paraphrased. “There’s no program director to impress. My record’s gonna get played.”

It’s important to note that Ludwig was very careful not to criticize other mastering engineers or their work. The discussion was focused on the loudness trend, to which he admitted being an unwilling participant. “It’s easy to go past the point of ‘still musical,’” he said as the session came to a close. “It’s easy to make a loud record.”