Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Advanced

Lesson Overview:

• Understand the basic elements of “Rhythm” changes.

• Learn to comp through different variations of “Rhythm” changes.

• Develop chord substitution strategies that will make your progressions more interesting.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

I doubt George Gershwin could have imagined the impact "I Got Rhythm" would have on contemporary music when he penned the tune in 1930. Since then, there have been countless variations, permutations, and straight-up imitations.

For several years I've been compiling a list of songs that use the basic progression in "I Got Rhythm"-now known in the jazz world simply as the "Rhythm" changes-in one form or another. My list is up to 175 well-known songs, including 25 percent of Charlie Parker's compositions, dozens of doo-wop standards, and what seems to be just about half of the pop/rock hits of the last 15 years by such diverse groups as Coldplay and Green Day. Let's take a few minutes (hours, days, years) to explore the many possibilities found within what is essentially a very simple chord progression.

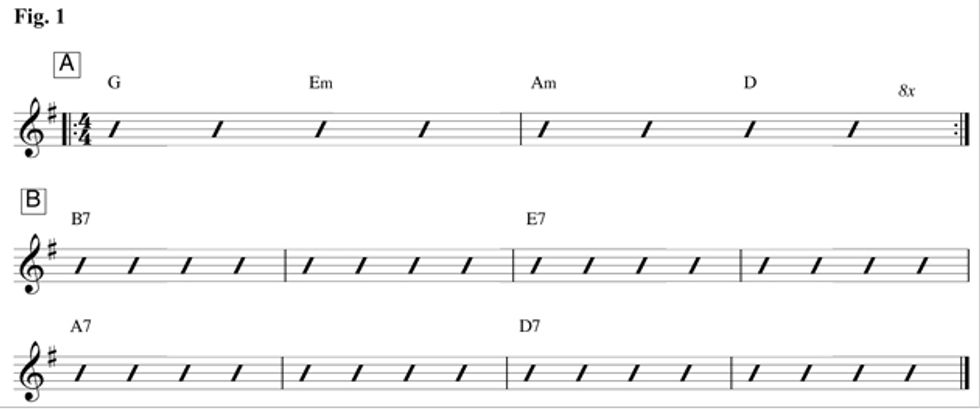

In Fig. 1, the changes for "I Got Rhythm" are stripped down to the most basic chords. The song's form is AABA-the A section twice (eight bars, two times), the B section once, and finally one more A section. Because this first example is simple and repetitive, I recommend singing through the song's lyrics to help you keep your place.

This progression offers an excellent opportunity to explore the art of chord substitution. Here's the basic principle: There are at least two chords that can be substituted for every original three-note chord, as long as the substitution shares at least two notes with the original chord.

For example, both Em (E-G-B) and Bm (B-D-F#) triads can be substituted for a G major (G-B-D) triad. For chords with four or more notes, there are as many as six logical substitutions.

For the most part, Fig. 2 modifies the chords from the previous example by adding the 7, 9, or 13 to create jazzier harmonies. So here, no chords are being substituted, just enhanced to add color.

Fig. 3 adds several diminished chords with C#dim (C#-E-G-A#) substituting for A7 (A-C#-E-G), which in turn can sub for the Am7 (A-C-E-G). We also add some hipper, bebop-style extensions-check out the 13th chords and the G7#5 in particular.

Finally Fig. 4 is a ridiculously busy and challenging Freddie Green-inspired variation that uses substitution, chord inversions (chords with non-root notes in the bass), and chromatic passing-tone chords to put a different chord on every downbeat.

I should point out that neither the late, great Freddie or any other experienced guitarist would ever play this many chords to accompany another guitarist, soloist, or singer. It's just too busy-but it sure sounds great in a music store!