Asking Iron Maiden guitarists Adrian Smith, Dave Murray, and Janick Gers to describe the differences in their playing styles creates something of a Rashomon effect, with each axeman offering a unique and sometimes contrarian view: “I think you can tell us apart very easily,” says Smith. “Dave and Janick’s styles are similar to each other, but they’re different from mine. They both have a strong Ritchie Blackmore influence. Dave plays more legato, whereas I do more muted stuff.”

“Personally, I like to try to be melodic but with a little fire and energy,” says Murray. “I think Janick’s the same actually—great melodies and spirit. Adrian is very methodical. He tends to work out some of his stuff, but he always sounds very spontaneous.”

Gers, for his part, sees Murray as the most melodic of the Maiden axe team. “Dave is very smooth—very rock ’n’ roll but with a beautiful tone,” he notes. As for Smith, Gers says, “He’s very rhythmic. Even when he’s soloing, you hear a certain kind of rhythm that’s different from what Dave and I do.” And for a self-assessment, he lets out a good-natured laugh and says, “I’m more of a ragged kind of player, rough around the edges but with a bit of a gymnastic edge.”

A fair amount of Maiden purists scoffed when the band expanded to the three-guitarist team of Murray, Smith, and Gers in 1999, fearing that the classic twin-axe interplay that all but defined the New Wave of British Heavy Metal sound in the early ’80s would be lost in an interminable sea of noodling one-upmanship. (Gers had replaced Smith after he left the group in 1990; when Smith returned to the fold, Gers stayed on.) But on a series of bracing releases—2000’s Brave New World, 2003’s Dance of Death, A Matter of Life and Death from 2006 and The Final Frontier from 2010—the trio pooled their individual strengths to form a potent metal guitar orchestra.

“I imagine you’d probably get three guitarists in other bands and it just wouldn’t work,” Murray says. “There’d be a lot of overindulgence and the songs would get lost. Somehow, we sidestep all of that. I think it’s like a bit of magic.” Smith agrees: “For the most part, our songs are quite long and maybe a bit indulgent anyway. There’s plenty of space for us to do our own thing and express ourselves without our egos getting in the way.”

Indulgence seems to be the very idea behind the recently released The Book of Souls: It’s the band’s first double record (clocking in at an ADD-busting 92 minutes), and all but four of its 11 tracks are nearly six minutes long—three, in fact, break the 10-minute barrier, with the album closer, singer Bruce Dickinson’s majestic “Empire of the Clouds,” about the 1930 R101 airship crash, ranking as the group’s longest cut ever at just over 18 minutes.

The elongated arrangements give the guitar team ample room to shine, but what’s remarkable about their performances—take the Thin Lizzy-sounding “Speed of Light” or the spitfire disc-opener “If Eternity Should Fail”—is the way they never seem to repeat a lick. There are no half-gestures or rote moves, and at times the fretwork even comes close to transcending the album’s material—no small feat considering this could be the band’s strongest set of songs in over a decade.

Premier Guitar sat down with Smith, Murray, and Gers to talk about the guitars and gear they used on the new album, how the blues figures into their playing lexicon, what it’s like to tackle an 18-minute bear of a song, and what steps they take to stay out of each other’s tonal space.

You’re all accomplished players, but do you spend any time at home woodshedding, working on your chops?

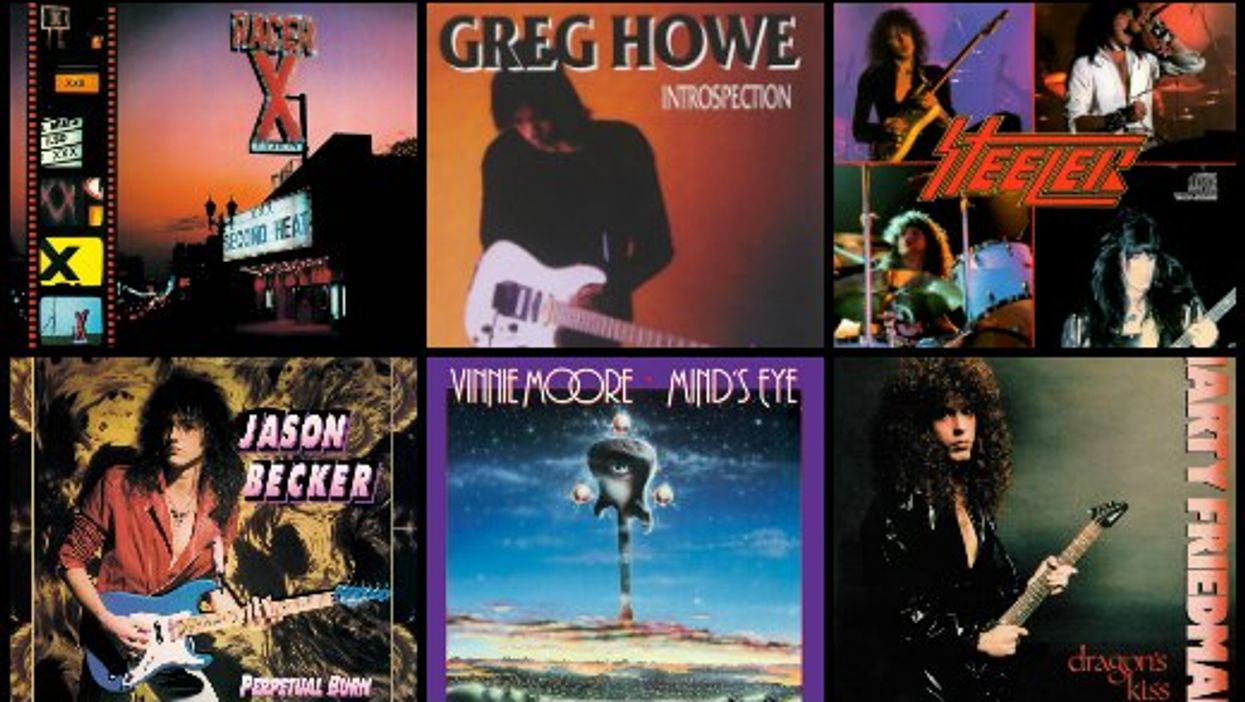

Smith: I definitely practice, especially before an album or a tour. I can’t do what some people do—you hear about Yngwie Malmsteen practicing for eight hours a day. That’s a long time to do just one thing. When I get time, I try to learn some new things and stay fresh. One thing I like to do is work new techniques into old material. Sometimes [bassist] Steve [Harris] will say to me, “Why are you changing that? What you had before is great, it’s melodic—it’s what people want to hear.” But you know, you have to try sometimes, especially with stuff you’ve played so much.

Murray: I think it’s like any profession. If you were an athlete, you’d exercise and warm up, and I think it’s the same with guitarists. If you just played guitar from tour to tour, it’d take a long time to catch up. But I like playing just for the fun of it—it doesn’t feel like work to me. When I’m at home, if I’m watching a movie or something, I’ll have a guitar on my lap, something with really heavy strings that’s hard to play, like an acoustic. That’s a good way of keeping my fingers limber.

Gers: I don’t consider playing practice—I’m just playing. I’ve got guitars all over the house. They’re all tuned differently, so wherever I’m walking I can just pick one up—standard tuning or whatever—and I’ll just play it acoustically. But you know, as far as practicing goes, I think you’ve got to experience life. You’ve got to experience everything in life, all the emotions, and put them into your guitar playing. If you sit in your room practicing all day, that certainly won’t happen.

So how do you go about channeling your emotions into your guitar?

Gers: You conjure up images and feelings. For the song “The Book of Souls,” for example, I thought back to being in Mexico and seeing the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon, just outside of Mexico City. All my songs and ideas will come from what I see or experience… a movie or some spiritual idea or whatever, somewhere I’ve been.

Do you ever come up with guitar parts you think are great, but they’re not quite “Iron Maiden” and don’t make the cut?

Murray: Absolutely. It’s happened a few times. Obviously, the band has an identity and a sound, so sometimes it’s “Yeah, that’s great, but it’s not right.” I’ve got a few things that never quite made it because they weren’t Maiden. I sit at home and put on a drum loop, and I’ll get an idea and stick it on my iPhone. Sometimes the idea fits, sometimes not. With Maiden, the quality of music is at such a high level that you have to reach high all the time. Anything below par isn’t really going to make it.

Gers: I think whatever we do sounds like us. Sometimes you’ll bring stuff in that doesn’t quite fit as well as something else, so you’ll go on to another idea. I don’t think I’ve ever brought something in that people said wasn’t Iron Maiden. Perhaps if it was totally blues it might not be Iron Maiden, but you could probably change it and it would work. What I love about Maiden is that there’s no restrictions. On this album, there’s so many different facets of music. I think “Empire of the Clouds” is almost like a Broadway musical. And you’ve got “The Red and the Black,” which has lots of classical connotations and Celtic riffs. “The Book of Souls” has an almost Eastern vibe to it.

Speaking of blues, it’s been said that the NWOBHM bands did away with blues structures. Do you agree with that notion? And if so, how do you fit bluesy guitar parts within arrangements and rhythms that aren’t bluesy?

Smith: Actually, my influences are very blues-rock—Pat Travers, Johnny Winter. I found it easy to pick up on what they were doing, whereas someone like Ritchie Blackmore, whom I love—you try to play “Highway Star” when you’re a kid, and it’s impossible. So you start off with the Stones, the Beatles, and then you go up to Johnny Winter.

Murray: I love the blues—Albert King, Albert Collins, Buddy Guy, B.B. King. With the sort of rhythmic things we do, you’d think it would be an impossible task to blend a little blues in, but you can do it. At times you kind of thrash around, but if you try to play nice melodic notes, you can cross over. If you listen to some of our stuff, obviously there’s heavy rock and metal, but there’s also classical melodies, jazz, blues—it all fits.

You’ve worked with producer Kevin Shirley before. He likes to get things in the can quickly.

Murray: Yeah, I love that about him, actually. I think he’s fantastic.

Smith: See, I’ve got mixed feelings. I give Kevin grief every once in a while because of that, working so fast. I’ve got a couple of amps in the studio, and I’ll be messing around and he’ll be like, “Come on. Let’s do it.” I want to see what the amps sound like—I want to be inspired. Kevin is very “plug in and I’ll record you.” There’s no smoke and mirrors. Quite often I’ll play a solo, and he’ll say, “That’s great. It sounds like you.” Then I’ll say, “I don’t want to sound like me. I want to sound better than me!” We clash a little bit, but I love him. He’s a strong personality.

Back in the day, you’d spend months overdubbing and layering. Is there pressure now to get the parts right the first time?

Murray: No, in fact it’s quite the opposite. I’ll tell you, I actually love working with Kevin, and I love how fast he works, all the Pro Tools and technology he uses. Back in the day, when you used reel-to-reel, everything took so long—it killed a lot of spontaneity. Now everything’s quick and almost on the fly. When we go in and record a track, we’re all playing together, Bruce is singing, and just like that we’ve got the foundation done. After that, when we go in to do the overdubs, I’ll go into the control room and sit next to Kevin, and we go through each of the songs bit by bit, changing things, playing solos or fixing chords. Kevin is fantastic: “This needs a punch-up. This bit, look at that.” And if you mess up, we can move something around and make it work. I’ll do three or four solos, and then Kevin will go, "Yeah, I’ve got enough.” So I’ll get a cup of tea, come back, and he’ll play me what he’s put together. Then I’ll go home and learn it for the next tour.

Smith: We’ve got three guitarists, so it’s hard for everybody to do all that tinkering. If Dave is sitting there doing a solo in 20 minutes, I’m not going to spend five hours working something out. You just can’t do that. Normally the first couple of takes are the best. If there’s anything I’m really unhappy with, I’ll fix it. Maybe I’d have spent more time redoing things in the past, but not now.

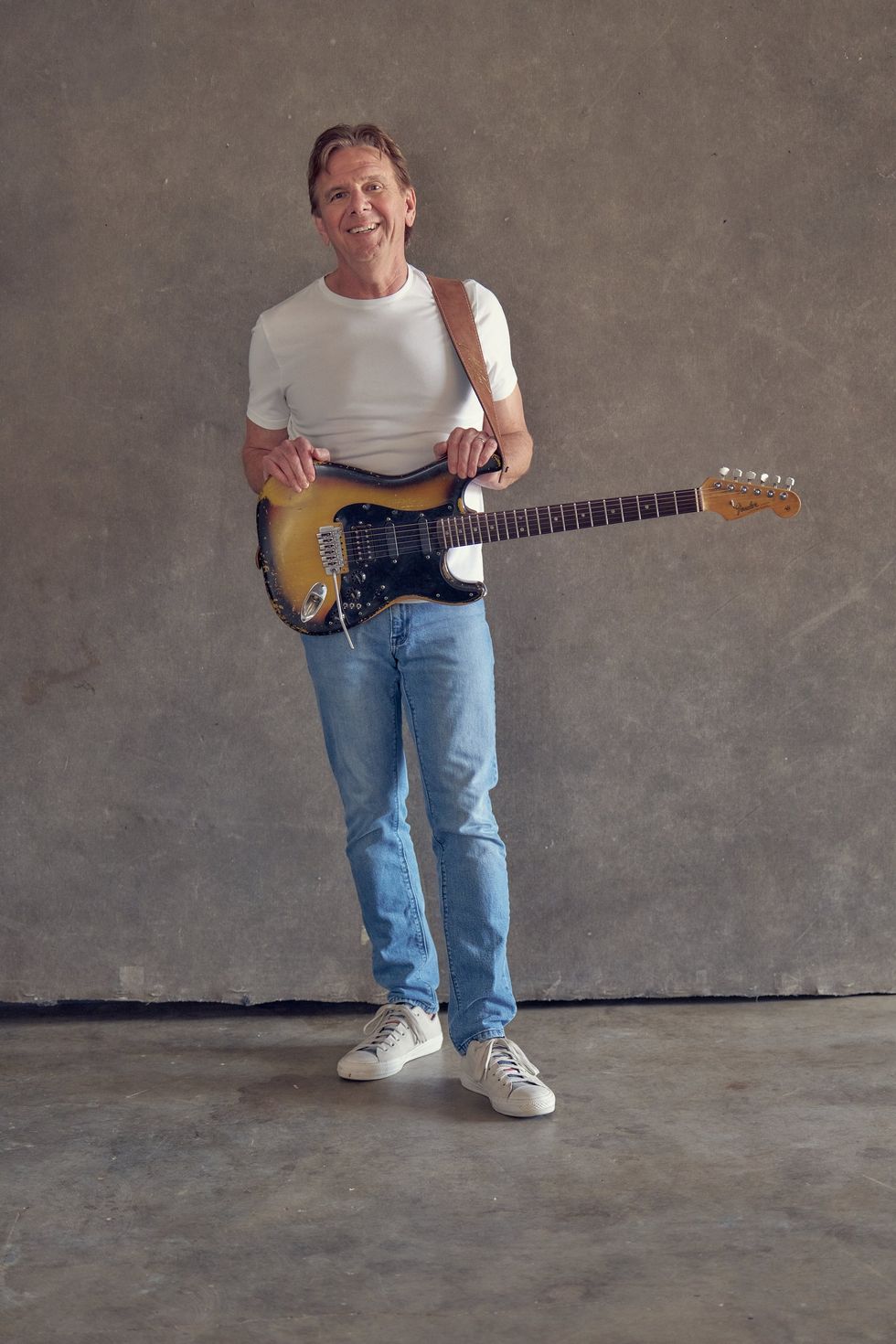

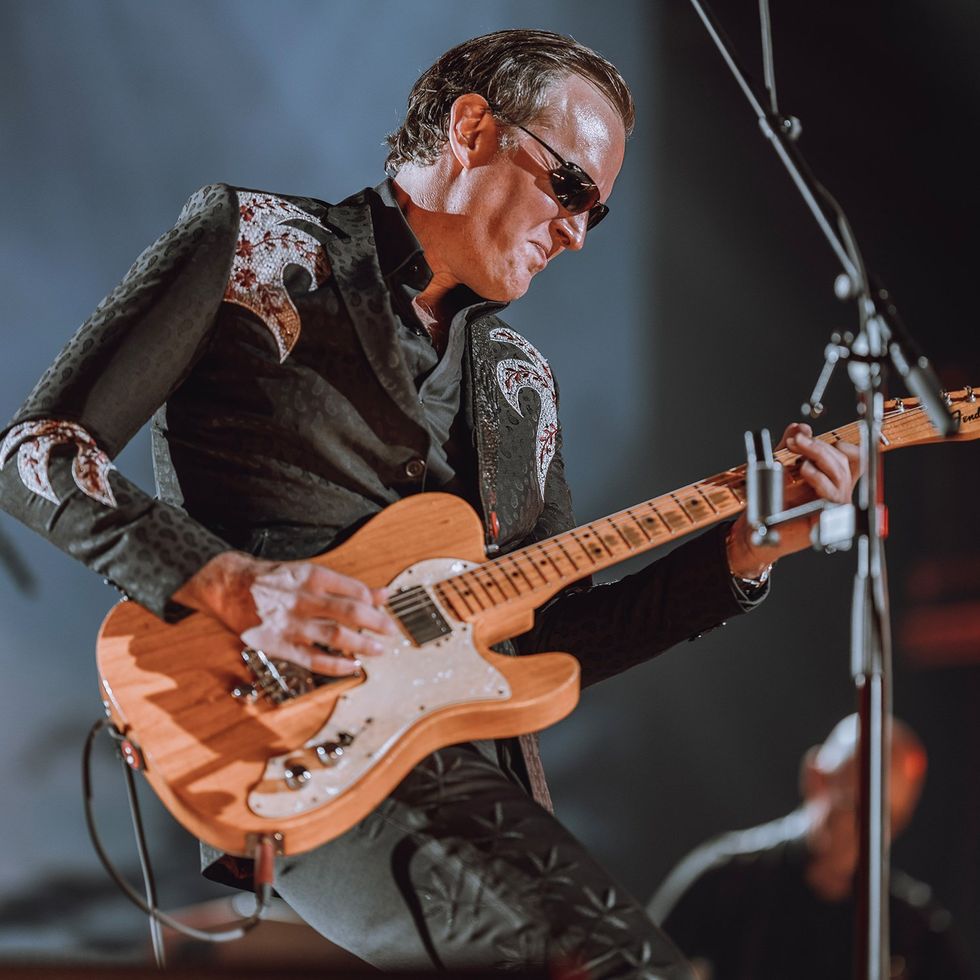

Photo by John McMurtrie

Do you have to get in a certain mood to do overdubs? It’s a little more scientific than playing in the room with the other guys, right?

Murray: Yeah, it is, but it’s not like you’re in a lab with a white coat on. I go in, I plug straight in, put on a Uni-Vibe or a Distortion +, maybe a flanger, and then I just feel it out. So no, you don’t have to sit down and cross your legs in a lotus position and go, "Ohmmmm.” [Laughs.] It was basically, have a couple of cups of coffee, get some adrenaline going, and then go for it.

Speaking of pedals, Janick, you’re not a big fan.

Gers: To me, they compress the guitar. And plus, it always feels a little bit too easy. I’d rather look for melodies and find other ways of making it interesting rather than just pressing a button. I’ve got no problems with that, although there are certain guitarists who will use pedals as opposed to trying something different. It’s just not for me. I’d rather turn the guitar down, let the amp scream, and change the sound that way. Kind of old fashioned, I suppose.

Smith: Yeah, but you still have racks—delays and all those things are in the racks. As for myself, I like to bring in one thing I haven’t used before per album. A few albums ago I went mad on the Whammy pedal. This time I brought in an Eric Clapton Crossroads pedal—a few settings on that sounded quite good. Sometimes it’s fun to let the sound take you somewhere. You spend a morning messing around with effects and you’ll probably get an idea for a song out of it. I know I do.

Adrian Smith’s Gear

Guitars

Gibson goldtop Les Paul

Jackson Adrian Smith Signature San Dimas DK (ebony and maple fretboard models)

Jackson King V

Amps

Marshall JVM410H

Blackstar Series One 104EL34, 1046J6, and H-T5

Effects

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

Boss CH-1 Super Chorus

Boss CS-3 Compression Sustainer

Ibanez TS808 Tube Screamer

DigiTech Eric Clapton Crossroads

Dunlop Cry Baby Wah

Duesenberg Channel 2 overdrive/distortion

Strings and Picks

Content

Dave Murray’s Gear

Guitars

Fender Dave Murray signature Stratocaster

1960s Fender Telecaster

1970 Fender Stratocaster (previously owned by Jethro Tull’s Martin Barre)

Gibson Les Paul Classic 1960 Reissue

Gibson Les Paul Axcess Standard with Floyd Rose

Gibson Memphis ES-Les Paul

Amps

Victory amps

Fender Super-Sonic 100-watt 2x12 combo

Effects

MXR Uni-Vibe Chorus

MXR Distortion +

TC Electronic Flashback Delay

TC Electronic Corona Chorus

Dunlop Cry Baby Wah

Dunlop JD-4S Rotovibe

Wampler Clarksdale Delta Overdrive

Phil Hilborne Fat Treble Booster

Janick Gers' Gear

Guitars

Fender Stratocasters, including a black Strat that was a gift from Deep Purple’s Ian Gillan

Amps

Marshall JMP-1 preamp

Marshall 9200 power amp

Effects

Marshall JFX-1 multi-effector

Did you use any new amps on the album?

Murray: Yeah. In fact, I started playing through a Fender Super-Sonic 100 2x12—you know, one of those tube amps that sounds absolutely amazing. Colin, my guitar tech, brought in a Victory amp—that was a new thing for me. I used one on the tail end of the album, and it was tremendous—very tubey, very old school.

Smith: I chop and change. When I rejoined the band, I was using an ADA with a power amp. Then I switched to the Marshall JMP-1s, which Janick and Dave were using. And then I thought I’d do something different and I went back to the Marshall heads. It’s a different sound.

Gers: I use Marshalls. The one I was using in the studio wasn’t a standard Marshall amp—it’s been picked around on by Mike Hill and a few other people at Marshall. It’s basically got two 100-watt slaves on it, and it’s got a front-loaded rack. I’m pretty much straight in there. That way, you’ve got more control over it, it doesn’t thin it out. I like to keep it live sounding and real. Then you can just turn your guitar up and down, whatever you want.

Dave, you said “tubey” before. Is that you doing the first solo on “Speed of Light”? That’s got a big tube vibe.

Murray: I think I do the first solo, and Adrian’s playing a lot of the melodies. I’m using the Super-Sonic on that, I think. I have to be honest: I got the album about a month ago, and I’ve played it several times, so I’m still hearing new things that I don’t even remember playing. [Laughs.]

Adrian, I read you were inspired by Eric Johnson for certain parts on “Speed of Light.” Also, you said that you rediscovered the pentatonic scale, which you use in the song.

Smith: Yeah, years ago I went through a phase where I was trying to figure out Eric Johnson, but I couldn’t even get close. He’s brilliant. Trying to say what I do sounds like Eric Johnson is a bit presumptuous, I think. Joe Bonamassa’s another one—the stuff that comes out of him, those pentatonic runs, is just incredible.

Janick, let me ask you about “Shadows of the Valley,” which you wrote with Steve Harris. There’s some beautiful guitar harmony parts toward the end. Is there a specific way you go about recording those parts?

Gers: When it comes to three-part harmonies, if Adrian is doing the song, he might put them all down himself. If it’s one of mine, I might do all the harmonies myself. Then later on when we come to do the song live, we work out the harmonies between the three of us. It’s whatever’s the simplest, whatever sounds best, really. Other times we might do a three-part harmony with all of us. You never quite know what’s going on.

It’s like the Stones: When you listen to what Keith is doing and what Ronnie’s doing, it doesn’t really matter about the individual parts, because it sounds brilliant. I love that when they ask Ronnie who’s the best guitar player, and he says, “I am.” Then they go and ask Keith and he says, “I bet Ronnie said he is. Well, he’s wrong. No one can beat us when we’re together.” And Keith’s right.

Adrian, the riff to “Death or Glory” is great. How do you know when a riff is just right?

Smith: Yeah, it’s interesting. There’s an intro and then a second main riff—I changed that a bit and made it double-time, because originally it was kind of Thin Lizzy. I made it sound more Maiden. I was just trying to write something that sounded immediate but with a big chorus.

Let’s talk about “Empire of the Clouds.” Guitar-wise, how did you guys wrap your heads around an 18-minute song?

Murray: When we went into the studio, Bruce was playing the melodies on the piano, and we started learning it, just by listening to him. He’d say, “Oh, yeah, I’ve got an idea for this bit and that bit.” So basically, when we sat down for the very first bit, I just wrote down a couple of chords and we jammed. It went from there—Bruce playing and us jamming live. We recorded it, because you should always document everything and keep it. You never know when you’ll have a keeper bit. We did the song in sections because, you know, it’s 18 minutes long! [Laughs.]

Smith: We did out parts in bits, and every so often Kevin and Bruce would say, “No, that’s too bluesy. Try it a bit more classical.” It evolved and turned into something pretty great. It was good fun to do.

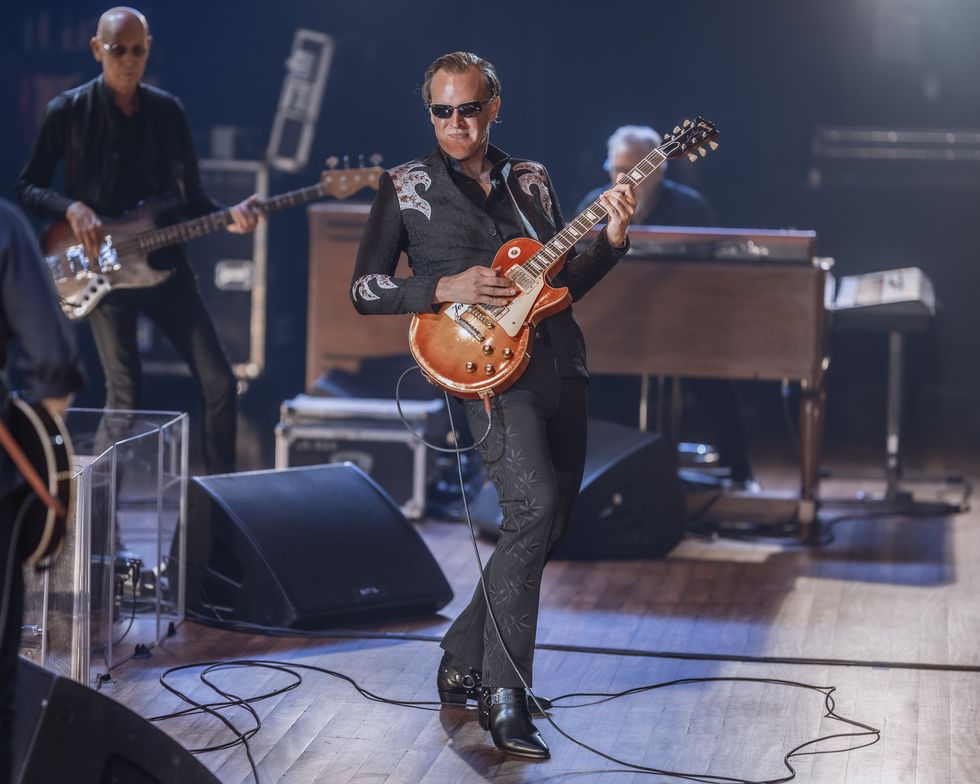

Photo by John McMurtrie

When you first heard it, did you immediately get an idea of which sounds to go for?

Murray: I did. I had a Les Paul plugged straight into the amp. I had the guitar set on the neck pickup and put the volume down low—it just seemed to fit. And I think the same with the other guys; we were just playing with the guitars kind of turned down quietly, and we felt our way through. As the song built, we increased the volume on the guitars, and eventually we got to the chord-heavy sequences. I’d say it was spontaneous, and that can make it hard to analyze.

Before we start the tour for next year, I’ll have to sit down and learn those solos. I’ll have to relearn all these songs myself. If you’re playing something in the studio, it’s not something you’ve necessarily spent a year working out. It just happened in the moment. But I think that’s where the magic is: It’s something that just comes out of thin air.

Dave, you’ve mentioned playing a Les Paul. I assume you played Strats, as well.

Murray: Oh, yes, I’ve got those. In fact, I used my signature model on every song. I’d swap guitars, play some melodies and rhythms on a Strat, and then maybe play something else on a Les Paul. I did use a Les Paul with a Floyd Rose on quite a lot of the songs. The signature Strat is a really nice, very playable guitar. A lot of guitars you get, they’re not playable. But they’ve made this one very comfortable to play, so I’m really pleased with that.

Janick, what about you?

Gers: There were three or four Strats—I’ve got a couple of custom Strats Fender built for me—and I was using them at different times. I couldn’t exactly tell you which ones, to be honest, it’s whatever felt right at the time.

And Adrian, you’re playing your signature Jacksons and a goldtop Les Paul?

Smith: That’s right, but I’ll tell you, the biggest thing, no matter which guitars we’re playing, is to pay attention to intonation. You get three guitarists on the same track, and you can get a bit of a sour sound.

I would think that might really come into play when you do harmony parts.

Smith: It’s not a problem with lead parts because you have vibrato, and because we have different vibrato styles, you can just blend everything in. It’s more with chords. If we’re all thrashing on the same chord in the same neck positions, you’re going to get intonation problems. I usually try to work it out in the writing, so we’re actually playing different things.

With harmonies, I’ll sometimes put a third in there, but that can sound a bit bland. Usually I’ll put in a low octave to beef up the bottom end. You’ve got three guitars but it’s not really a three-part harmony. Sometimes you double a part for a Celtic sound—it can sound like bagpipes.

Dave and Janick, because you both play Strats so much, how do you avoid occupying the same tonal space?

Murray: We put “No Entry” signs up. [Laughs.]

Gers: I think we have different sounds. Adrian has a much more compressed sound, Dave a little less so, and when I put my guitar in the middle, the tonal characteristics seem to work to make the band sound bigger. That’s how it feels to me. I constantly change the pickup selection and move the volume around, which can be troublesome when you’re trying to overdub. I’m never quite sure where it’s sitting, so I play it by ear. I might turn the guitar down to 2 or 3 at some point, and then whack it back up. I’m constantly changing things.

Murray: For some reason, the way we play makes the actual tones of each guitar completely different. I mean, you can hear Janick’s tone, Adrian’s tone, and my tone, and you know who’s who. All the sounds are different, but for some reason that’s hard to understand, they just fuse together. That’s the unknown known, where something just happens and you can’t analyze it.

YouTube It

There’s tons of triple-guitar goodness in this Iron Maiden concert from the 2014 Rock am Ring festival in Nuremberg, Germany.

When you’re playing live, do you watch one another’s hands? “He’s playing hard, so I’ll play softly”—that kind of thing?

Murray: It’s not a case of watching each other, it’s more about the dynamics of the song or section. So maybe one of the guys is playing a little heavy, but then the other guy might be playing something lighter or sweeter, and that adds a cool dynamic. Basically, we could be playing one section of a song, but we’ll be playing different parts and they all work together. We could play three-part harmonies if we want, or we could play one rhythm and two kinds of riffy things—it’s limitless, really.

Gers: The trick is to make the guitars sound like one powerful sound. We’re not trying to stick out. You ask, “Well, what did you do on this song or that?” Listen to it—you can hear it. Without one of those guitars in there, it won’t sound like it does.

Smith: I tend to be precise. It’s very easy to cheat onstage—you do windmills and whatever. Yeah, you watch what the other guys are doing, and you’re listening. Most of the time it works without a whole lot of effort.