For guitarists, the name Dumble conjures awe, wonder, critique, devotion, myth, and plenty of conjecture—all of it understandable. The late Howard “Alexander” Dumble’s namesake amps are akin to the vaults of Fort Knox: We know they exist, we’ve heard tales of their unimaginable treasure, but few have, or ever will, experience them firsthand.

The mystery stems from how Mr. Dumble kept a tight-knit circle of friends he trusted with his amplifiers. That’s why, when he passed in 2022, many wondered what would become of his builds, designs, and company. Fortunately, Dumble had a plan and entrusted the keys to his kingdom to two of his closest friends: Drew Berlin and Matt Swanson.

Judging by Berlin’s résumé, the brand is in good hands. An early adopter of the amplifiers as a professional guitarist, he even helped Dumble voice many of them. But beyond the Dumble sphere, he is a titan of the vintage guitar gear community. As one half of the famed “Burst Brothers,” he was key in shaping Guitar Center’s early vintage program and still deals in some of history’s most priceless, sought-after, and collectible guitars and amps.

Berlin’s connection to Dumble was far more personal. From the day they first met until Dumble’s passing, their friendship centered on caring for each other, whether that meant amp modifications or healthcare. Berlin was a constant presence.

“I even had a deal with my wife where, if I wasn’t home by midnight, she’d call Mr. Dumble,” he said with a chuckle. “He was so charming. He’d sweet-talk her: ‘Oh yes, Diane. Drew’s here, and we’re getting a lot done. He’s really helping, so I’ll need him a bit longer.’ And she’d say, ‘Okay.’ [laughs] That went on for 20 years.”

Here’s “Woody,” a Dumble Special that was often used to “audition” potential customers. It’s a single-channel design that has beautiful, smooth compression. And like many of Dumble’s amp designs, there’s nowhere to hide.

At 74, Berlin’s love and devotion to Dumble and his amps remain unwavering. While many are lucky to glimpse one in person, he owns several, still gigging them regularly. More crucially, he and Swanson own the brand’s name and trademark, a job he takes very seriously setting up the Dumble Preservation Society to safeguard everything, service existing Dumble amplifiers, and, though he didn’t know it at the time, build new ones.

But before anyone questions his motives, it’s vital to understand where Berlin is coming from. His passion for the amps and profound devotion to his friend and the legacy he left was even visible over our video call from his California recording studio. Every decision he makes balances protecting the legacy with navigating the future, and is always guided by the question, “What would Mr. Dumble have wanted?”

Thankfully, if anyone can answer that, it’s Berlin. And he was generous enough to share why that is with us.

How did you and Mr. Dumble first meet?

I knew about Dumble and the tone in the early ’70s, and I started becoming more and more familiar with it, of course, through Jackson Browne, David Lindley, and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Because of that, and being that I was “the vintage guy,” a mutual friend, Jim Foote, thought that it would be interesting for Mr. Dumble to meet me.

He set up an appointment, and Dumble came in with a small Special called “Woody,” which we actually just displayed at NAMM. I plugged into the amp and started playing, and we started talking. Within an hour or so, I went and got one of my amps from home, and he modded it for me. And that started the relationship.

It began with gear, but it seems your friendship grew into something much deeper.

You know, it absolutely did. He was brilliant, and we had a lot in common beyond music. So, I started trying to be there for him as much as possible, sometimes like eight or 10 hours at a time, day after day after day.

Pretty soon, it was hard for him to get around, so I found a vehicle for him and was able to help him out. I felt really honored to be able to do that, because I was getting such great advice from him, and he was really intelligent on so many levels. My family even did a lot of outings together where we included him as part of the family. He loved my children, so they grew up knowing him as Uncle Alexander.

Given your close connection to both the man and his amplifiers, what would you say defines the “magic” of his amplifiers?

He liked to say that the frequencies were enhanced, and there were more highs, more lows, more mids. It was a blossoming of frequencies. Most of his amps were touch-sensitive, so if you dug in harder, it would change the tone. You could express more, and notes would do different things.

But as far as for me, it's more than just something that you hear. When you're playing it, the expression that you're able to create, it's something you feel in your chest, in your heart. And I like that they never hurt. Some amp tones are irritating and hurt your ears, especially if it's too loud. Dumbles never did. The louder, the better.

At first glance, this would appear to be a Special, but in 1989 Dumble modified it to be a 150-watt Steel String Singer for Stevie Ray Vaughan while his SSS was in for repairs.

Players often point to the Steel String Singer’s cleans and the Overdrive Special’s distortion. Did Dumble approach those as separate designs, or did he see a unifying thread in his creations?

It was very important for him to be really happy with the way the amp sounded in the clean, lush mode before you kick in the overdrive.

The way he explained it, it starts in the power section of an amplifier. It needs to be clean, powerful, and warm. Then you get a really warm, clean, lush sound and add the overdrive section to that. Getting that right is more challenging than the overdrive section. The overdrive was a balance of how much crunch you wanted and how much sustain. So that was secondary.

There are rumors of the incredible time he took building each amp and how particular he was about every detail. Are they true?

Yes. And he liked to do everything himself. He never let anyone even touch a build that he was working on. I understand now more than I did, as far as how difficult and how time-consuming that was.

He would change out 20, 30, 40, or 50 parts on an amp. It would take forever. And then after he finally came up with the right combination, the artists would come over and play it. If it wasn’t quite what they wanted, he’d go back to the drawing board. And it took several tries, in some cases, to get the amp exactly where the artist and Mr. Dumble both agreed was the right sound.

Then he’d have to make sure that it was roadworthy before he would send it out on the road.

“Some amp tones are irritating and hurt your ears, especially if it's too loud. Dumbles never did. The louder, the better.”

How did he sustain that level of commitment and detail throughout his career?

Well, the amps were so complex, there were so many stages, and there’s so many different variances that it did become overwhelming towards the end of his life. He stopped making Steel String Singers and Overdrive Reverbs a long time ago because they were too much work. There were 11 Steel String Singers, and I think 12 Overdrive Reverbs were made. But he stuck with the Overdrive Specials. He had some health issues on and off through the years, so he did the best he could.

Did you and Dumble ever discuss your role in the future of his brand?

Well, we talked about it. My partner, Matt Swanson, and I were left to protect Dumble, his legacy, and his intellectual property. And a lot of people showed interest in wanting to take the Dumble name. The trademark was expiring and we had to act.

That’s when we started the Dumble Preservation Society. We offer amp service with the right schematics and parts. We have two techs. One was a close friend of Dumble’s that he personally approved, and the other is incredibly passionate and skilled. Since Dumble passed, we’ve serviced over 50 of his amps.

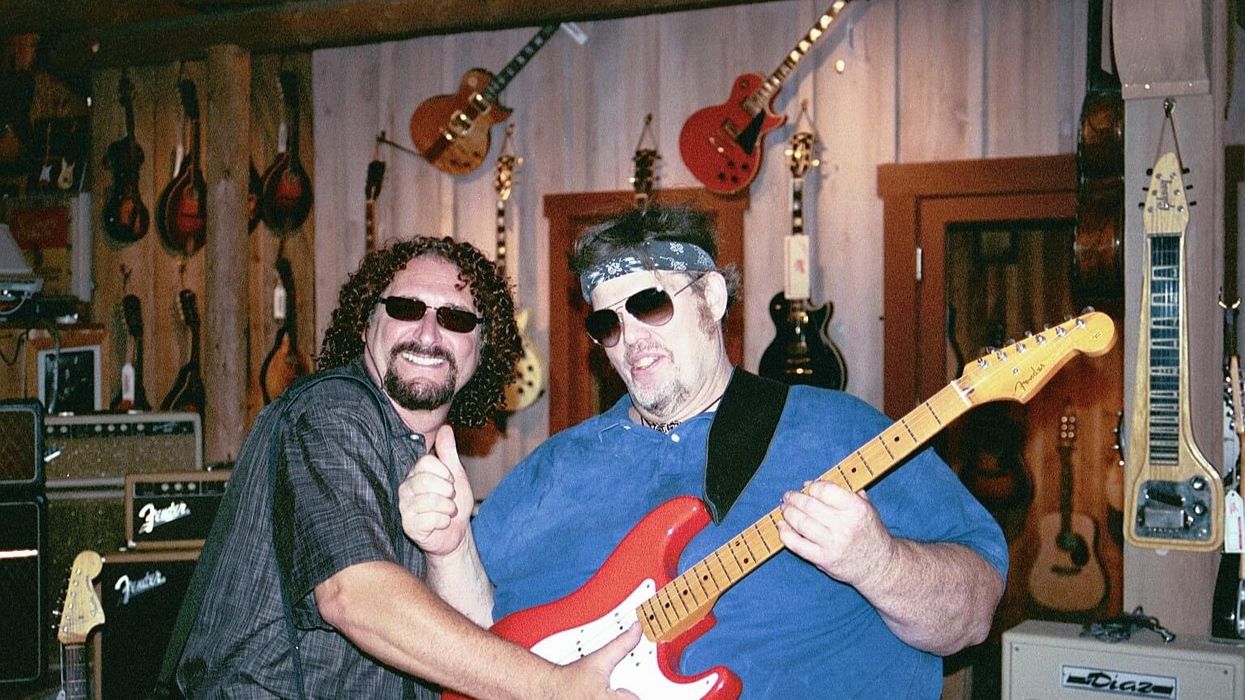

Matt Swanson (left) and Drew Berlin set up the Dumble Preservation Society to safeguard the brand, service existing Dumble amplifiers, and, though they didn’t know it at the time, build new ones.

Was your initial focus just to maintain the amps he’d already built?

That, and honoring his legacy. There’s so much he created that you hear all the time on records, in movies, on the radio. His sound is everywhere. It’s important for people to understand what he did. The Preservation Society stems from that: keeping awareness of his tone and his genius, servicing amps, and secondarily, building them.

What led you to start building new Dumble amps?About six to eight months into his passing, we found out that in order to keep the trademark, we had to actually manufacture and sell something. That’s when I made the decision. It wasn’t about profit. It was either do it ourselves or let someone else take it. He left us in charge for a reason, and he trusted our judgment.

Who’s building the new amps?

There are two guys, who don't want recognition. They don’t think it’s important, and I respect that. One is someone I’ve known and trusted for 35 years. He’s an incredible technician who was very close to Dumble. He told me he had promised Dumble he wouldn’t use any of the knowledge Dumble had shared with him to build amps. I said, “I understand that, but would you rather have people who didn’t know Dumble, weren’t connected to him, and aren’t trying to preserve his legacy do this? Or would you rather help us do what’s necessary?” He agreed.

Another is a friend who I’ve known for at least 20 to 25 years. He’s an amp repair tech who’s incredibly knowledgeable and passionate about Dumble amps. When things needed to be done and Dumble couldn’t do them himself, this was one of the only guys he ever trusted with anything.

You’ve mentioned several close associates deeply connected to and influenced by Dumble. It’s like he was building his company the whole time.

You’re right. He kind of was. I don’t think it was chance that he put us together.

I had been taking care of him for years, and he and Matt became great friends. One day, Dumble pulled him and me aside and said, “Drew, I really appreciate everything you’ve done, but I think moving forward, you’re going to need Matt’s help.”

I think he understood that we would need to work together to keep his legacy alive. I’m really grateful because I couldn’t have accomplished a lot without Matt. Together, we’ve kept the Dumble name alive and treasured, and that’s what we wanted to do.

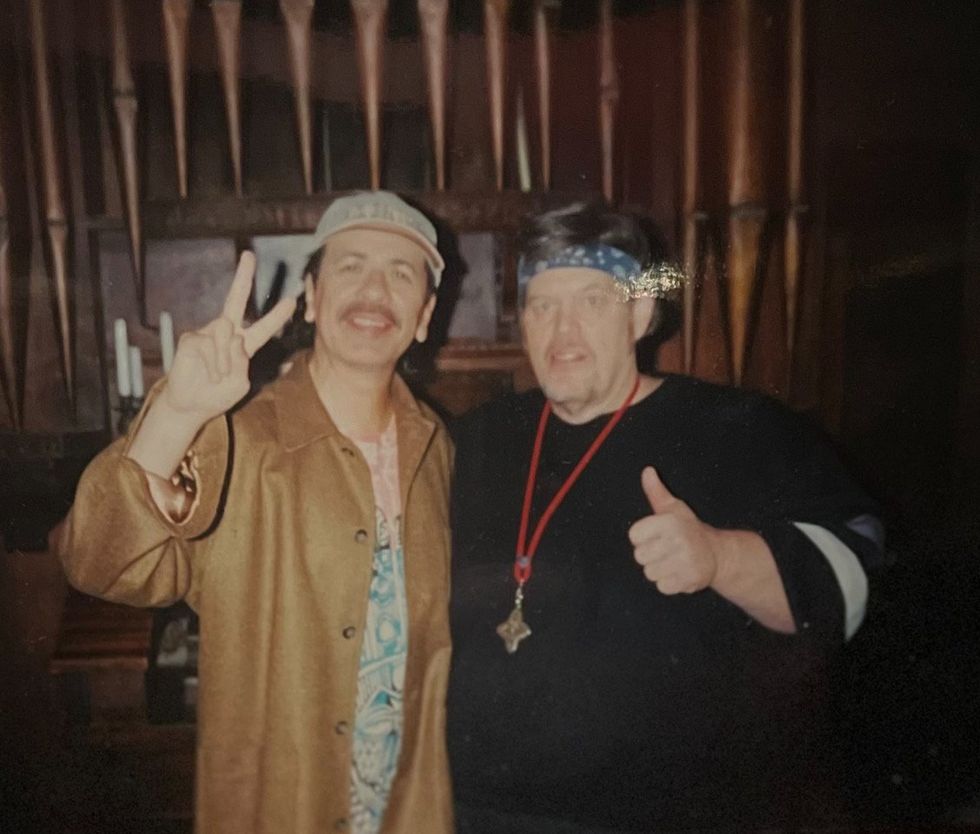

One of Dumble’s biggest supporters was Carlos Santana, who owned several Dumble amps over the years.

With the new amps now emerging, what can players anticipate from this next chapter?

I wish I could answer that, but I’m not sure where we’re going in the future or how we’re doing it. I can tell you, the few that we’ve made were very time consuming, as if Mr. Dumble did it himself: hand-cutting the boards, everything done by hand, the parts being as close as possible to what Mr. Dumble was using. We’re trying to get the sound as close as possible, to where you don’t just hear it, you feel it.

Right now, it’s just a handful of players, the Dumble family, in a way. I helped screen people for Mr. Dumble that I thought were great players and great people, people worthy of his amps. It’s still got to be like that. So, right now, we’re working with a few of Mr. Dumble’s favorite players, giving them some amplifiers and trying to tweak them the way he would have.

Are you adhering closely to Dumble’s original designs with these new builds?

We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel right now. We’re happy if we can get our amps sounding really close to what Mr. Dumble did. We're not trying to enhance or come up with new ideas for them, at least not at this point.

For those who’ve played the new amps, what’s been their reaction so far?

Well, the first one we did has already been on a couple of sessions. It went to a really talented pro player, and we’ve heard nothing but good things. And, a couple of weeks ago, I had a session where I brought one of the amps we had at NAMM. I have several Dumbles I use, and I kind of forgot that it wasn’t one of mine.

It’s exciting to have people playing them, wanting them, and wanting to take them on the road and record with them. Seeing guys I really respect, players, producers, and people making records really like it gives me confidence. The magic that Mr. Dumble had, his ears, his musical talent, his experience in electronics, I don’t see anyone else having that combination.

You stayed out of the design and building process during his lifetime. How do you think that shapes your perspective for what you’re doing now?

Now that we’ve done this, I feel like maybe it would have been better for him if I had pushed a little harder to let people help him when he was alive. He just wanted to do everything himself. I really appreciate that about him, but I never pushed him to say, “Let me help you.” I helped him in other ways, but I never got involved in building amps or letting others help him.

As both a fan and a friend, where do you hope to see the Dumble brand head in the future?

I wish I could give you an exact response, but I don’t know fully right now. This is still new for me, and I’m not sure where it’s going or how I’m going to feel about it.

I do know that as long as the brand is respected, I’ll be okay with it. If people could understand that Dumble did this from his heart. He had the magic to give people something to create with, and that’s what he lived for. He wanted to give artists a tool to help them become better musicians. As long as I can help carry that forward, I feel like I’m doing something useful.