Long before boutique pedals took over the world, Robert Keeley was there. Growing up in a musical family with a long line of electrical engineers sparked a circuit-bending obsession with tone. It wasn’t long before young Keeley was modding existing pedals, adding switching options inspired by high-end car audio equipment. This unique approach laid the groundwork for what would become one of the most respected brands in guitar effects: Keeley Electronics.

Starting with celebrated platforms like the Boss Blues Driver and Ross Compressor, Keeley’s early mods—namely, the Super Phat Mod overdrive and his flagship Keeley Compressor—became icons. Nearly 25 years ago, his overdrive and compressor were seemingly everywhere, overnight. Even guitar royalty got in on the action.

“It didn’t take very long,” Keeley admits, explaining the ignition of his initial overdrive box. “One time, Dave Weiner [former Steve Vai rhythm guitarist] said, ‘Steve has some DS-1s he wants you to mod.’ I said, ‘Send them my way!’ I called it the Ultra Mod after his album, Alive in an Ultra World."

Unfortunately, success also brought challenges. For Keeley, the early years of the boutique boom were clouded by addiction, loss, and hard lessons that would sink most small builders. While competition was springing up everywhere, he was losing his marriage, his health, and his company’s momentum.

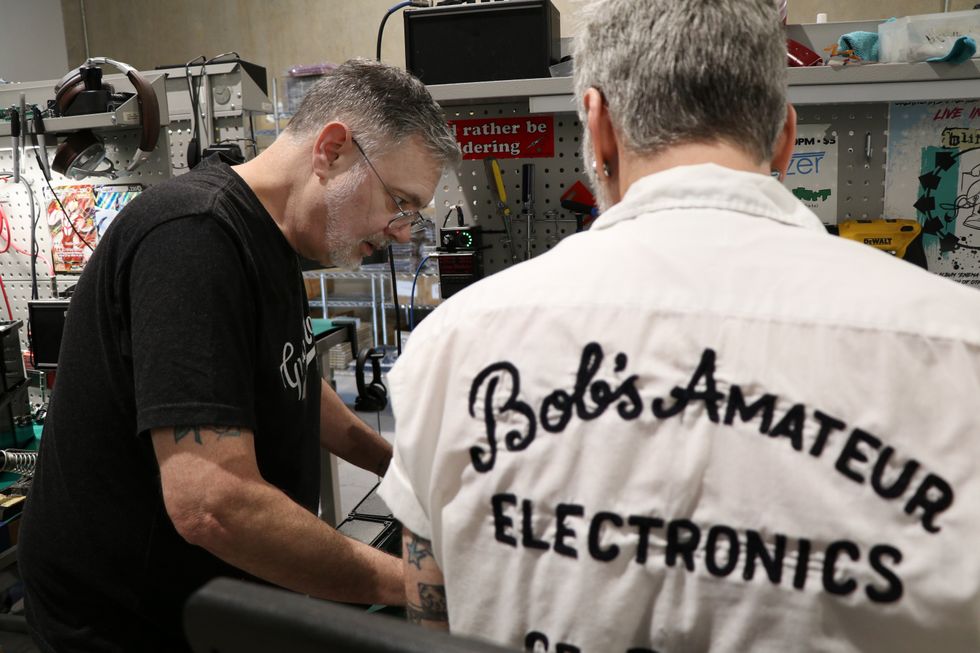

We’re not sure who Bob is, but there’s no room on the workbench for amateurs at Keeley.

Yet if there’s one thing this story makes clear, it’s that Keeley refuses to go quietly. What emerged from the darkness wasn’t just a revitalized company; it was a new era. Today, Keeley Electronics, which employs 35 people, is an industry leader. And through it all, Robert Keeley’s joyful and passionate outlook still permeates everything he says and does.

In this conversation, Keeley opens up about surviving life’s boom and bust cycles, the freedom of keeping everything in-house, and how Phish’s Trey Anastasio inspired both his first compressor and most recent Manis overdrive.

Your compressor seemed like an overnight success. What was it like rocketing from “I want to try modding pedals” to suddenly being the Compressor Guy?

It was a whirlwind. I was working at a stereo store repairing high-end audio gear when I found out Trey Anastasio used a thing called a Ross Compressor. I looked on eBay, and they were $400 each. There was no way I could afford that, so I bought the parts and made it myself.

“I think pedals will be around for a very long time. They’re the quickest, cheapest way to get inspiration between your guitar and amp.”

I was following [guitar electronics guru] R.G. Keen’s articles about the Ross Compressor. He’d explain circuits and offer little tips, like when Ross improved the power supply with an extra capacitor and resistor. I’d think, “What if I make it even better? If I use stronger transistors and tweak the circuit, I’d get a better compression sound.” Once I heard it, I thought, “This is amazing.” I put one up on eBay to sell and used that sale to buy more parts.

Your pedal mods, like those on the Blues Driver, were also massive hits. What got you into working with pre-existing pedals?

Well, I also wanted to capture the sounds of the Tube Screamer Trey was using. And for me, it’s always been, “What if I [swap components], combine them, and solve some tone problems at the same time?” So I looked at all the complaints on Harmony Central—“not enough bass, tone control doesn’t work, needs more gain, needs less gain”—and made mods that solved most of those complaints.

I was also like, “Man, I could do some mods like I see on car stereos, where they have a little switch for a bass boost.” And that’s how I did it in the beginning.

Robert Keeley says that the Manis Overdrive was inspired by Trey Anastasio’s unending quest for tone.

Those Blues Driver and Tube Screamer mods eventually became the Keeley Super Phat Mod and Red Dirt, but why did it take so long to release them as your own pedals?

I didn’t want to just copy something to make my own drives. I still had an ego. I didn’t want to just say, “Here’s my modded Tube Screamer.” But when you get in trouble with the IRS and have to pay $13,000 a month in alimony, you’ll do a lot for money, including putting out a pedal called the Red Dirt. [laughs]

I had to punch like a businessman. Besides, I couldn’t start a business with just one pedal, and people got tired of “the Compressor Guy.”

“Everyone told me, ‘Just declare bankruptcy.’ That was the last thing I was going to do.”

You’ve been very open about a lot of your early struggles. But while that can derail a lot of small businesses, you’ve always found a way to overcome. Why do you think that is?

I developed that during my divorce. I was so high on pills that I wasn’t paying taxes. My wife was embezzling $170,000 a year and not reporting it. Then she hired attorneys for an alimony case, so I had to pay back a quarter million to the IRS, and owed a million in alimony and child support.

Everyone told me, “Just declare bankruptcy.” That was the last thing I was going to do. When you’re dealt that kind of news—and won’t give up—you think, “I need to sell pedals by Friday to make payroll!” It was survival.

You definitely survived—and thrived. The 2000s through 2020 were huge years for pedal companies, and it seemed like every release you put out was a hit. What was that period like for you?

It was really fascinating because in those early years my sales doubled. It seemed like anything I made would sell itself. I was also bringing all the processes back in-house. My shop had burned in 2009, so all my cases were being drilled and powder-coated elsewhere, and then printed by another firm. I was bringing things back in-house and having to learn how to do everything again. But I get endless lucky breaks. [Keeley signature artist] Andy Timmons came on at the right time; that guy can move gear like nobody’s business. And we just got to the next level in our DSP.

“Trey Anastasio’s tech texted me and said, ‘It’s the perfect time to send Trey a bunch of your Klon ideas.”

Speaking of DSP [digital signal processing], you’ve grown far beyond compressors. What led you down the digital path?

It’s the people around me. My wife’s son, Craighton [Hale, Keeley Electronics engineer], was going to school for electrical engineering, so we had an electronics-minded person working with me. And our longest-running employee, Aaron Tackett, got tired of CNC work. I said, “How would you like to learn programming and help me with DSP?” He said, “Yeah, okay, I’ll do that.” And my god, did he take after it!

I love setting people up for things. I’ve been fortunate to have enough business coming in to pay these people well while they learn. Then they become superstars.

For greater design flexibility and control over supply, Keeley Electronics has brought enclosure building and other aspects of the manufacturing process in-house.

You share the spotlight with your team, have someone cooking for them, and give them a four-day workweek while still paying for 40 hours. That’s not something many employers offer.

I just like being nice. They thought free lunch was fine, so I went, “What if we make Thursdays the greatest day ever?” Also, I can't stand seeing my son-in-law paying over a grand monthly for health care, or employees being afraid of creating families because they can’t afford insurance. So I’m paying 60 percent of their health insurance. And I know how important it is to have three days off to feel human, get business done, and relax. I try to kill them with kindness. One day out of the year I might be demanding and yell, “Get that shit done!” Then I go back to being Santa Claus.

You’ve been through a lot over the years. How do you continue to take such pride in your team and the work you do together?

It seems like the only right way to do it. I’m always trying to say, “Why are you worrying? Let’s solve the problem so we don’t have to think about bad possibilities.” Besides, no one buys a downer story. But if you say, “I’m so proud of this pedal I designed,” people get interested.

Keeley Electronics seems to be entering a new era—your pedals have a fresh, more modern look, and you’re combining digital and analog in innovative ways. What’s inspiring this approach?

What started this wave was the freedom to expand our ideas and get out of the silly Chinese, prefab enclosures. Around 2020, I thought, “What machine can I buy to make them here?”

Now, having our own cases lets us design how we want. We developed this thing where I can put two circuit boards in there. The Noble Screamer was our first pedal like that. We could never have fit that in a standard box. Now I’ve got a prototype for next year—the Stereo Caverns—with delay, reverb, MIDI, expression pedal, stereo in and out, and presets. It’s all in there. That freedom started this wave.

“If I hadn’t had the success of the Octa Psi, I would be darn-near crying in my beer. But that’s the story of my life! I’m very fortunate.”

You do much more than just build enclosures. How did you evolve into a vertically integrated operation, managing so many parts of the production process in-house?

Every time the court system or the IRS would say I had to pay something else, I couldn’t get any credit with my suppliers. So, I would bring the whole procedure back in. I’d get a loan-shark-type loan for a powder coating thing or a CNC machine, and just sit down with my guys and ask them to figure it out.

It’d take, sometimes, a couple of years to figure out how to do a process, but eventually I built everything. Now we have four UV LED printers. We have four CNCs. I have a 3-kilowatt fiber laser. I have a CNC press brake. I have two powder coating booths, ovens, and spray booths. You just take it one piece at a time. You buy this equipment, and you know, “In about two years, I’ll pay it off, and I won’t be dependent on anyone anymore.”

Doing so much in-house probably insulates you to some extent, but how are tariffs and the changing market affecting the company?

I have to admit that last year things really slowed down for me during the summer. And if I hadn’t had the success of the Rotary pedal and our Zoma reverb, it would have been very, very scary. And then, as we rolled into this new year, the tariffs have been very expensive. If I hadn’t had the success of the Octa Psi, I would be darn near crying in my beer. But that’s the story of my life! I’m very fortunate.

Also, I put all my eggs into the DSP basket. It really paid off, because it’s very hard to do that stuff. I’ve got my spectrum analyzer looking at the smallest minutia of noise and frequency response details. By the time you get back to analog drive pedals, you’re dialed in.

Is that what happened with the new Manis overdrive?

I can actually tell you how the Manis happened. Justin Stabler, Trey Anastasio’s tech, texted me and said, “It’s the perfect time to send Trey a bunch of your Klon ideas. He wants to audition them.” I said, “I’ll have something in a couple days.”

I walked out of my office, went to Craighton, and said, “I want to try Russian germanium transistors and see if they have a different forward voltage than [Klon creator] Bill Finnegan’s germanium diodes.” Craighton had also been working on a bass boost that lets more bass into the clipping section. I said, “Great! Design it up.”

We sent two to Trey, and he messaged me saying, “Dang, I tried to go back to a Tube Screamer and I kept wanting the Manis.” Now he's saying, “I want my first custom signature pedal. I want Keeley to make me a new Boomerang [a popular looper pedal]. I don’t like the new Boomerangs, and the old ones are always breaking on me.” So I’ll spend the next couple years working on that. It’s fun.

Robert Keeley says the success of the Octa Psi, the Rotary, and the Manis have kept the company rolling smoothly during recent market challenges.

A couple years means you’re pretty confident in the pedal market, even with everything going on currently. Where do you think things are headed?

It’s still the golden age of pedals, but you’ll only have true success if you bring something new to the market. If you're just saying, “I’m doing the best Tube Screamer,” that ship has sailed.

I think pedals will be around for a very long time. They’re the quickest, cheapest way to get inspiration between your guitar and amp. And they’re malleable. You can put this one here, that one there, give it to your friend, get it back, find a video, and try something new.

What’s a pedal you've always wanted to make, but haven’t yet?

Number one is a MIDI “Klon” with digi-pots. It’d be an analog drive pedal with presets and MIDI control. Nobody’s doing that. I’d get to create a new category.