In the pantheon of popular country music artists, Marty Stuart has always been both an anomaly in Nashville and one of the genre’s biggest champions. How else to define the man who scored a 1992 hit with “Now That’s Country,” a twangy paean to the virtues of a simple rural life, while the same year humorously eschewing the Nashville signifier of the day, the cowboy hat, on his No Hats Tour with Travis Tritt?

Meanwhile, behind the scenes he was quietly amassing the largest known private collection of country music memorabilia in the world—which, of course, includes more than a few cowboy hats alongside rhinestone-studded Nudie suits, handwritten song lyrics, classic musical instruments, and a century’s worth of ephemera.

And despite earning bulletproof bonafides by serving as a sideman to country-music pillars Lester Flatt and Johnny Cash, tours of duty that occupied more than a dozen years and turned him from a teenage prodigy to a touted major-label artist, his interests outside of Nashville have become a large part of his musical life.

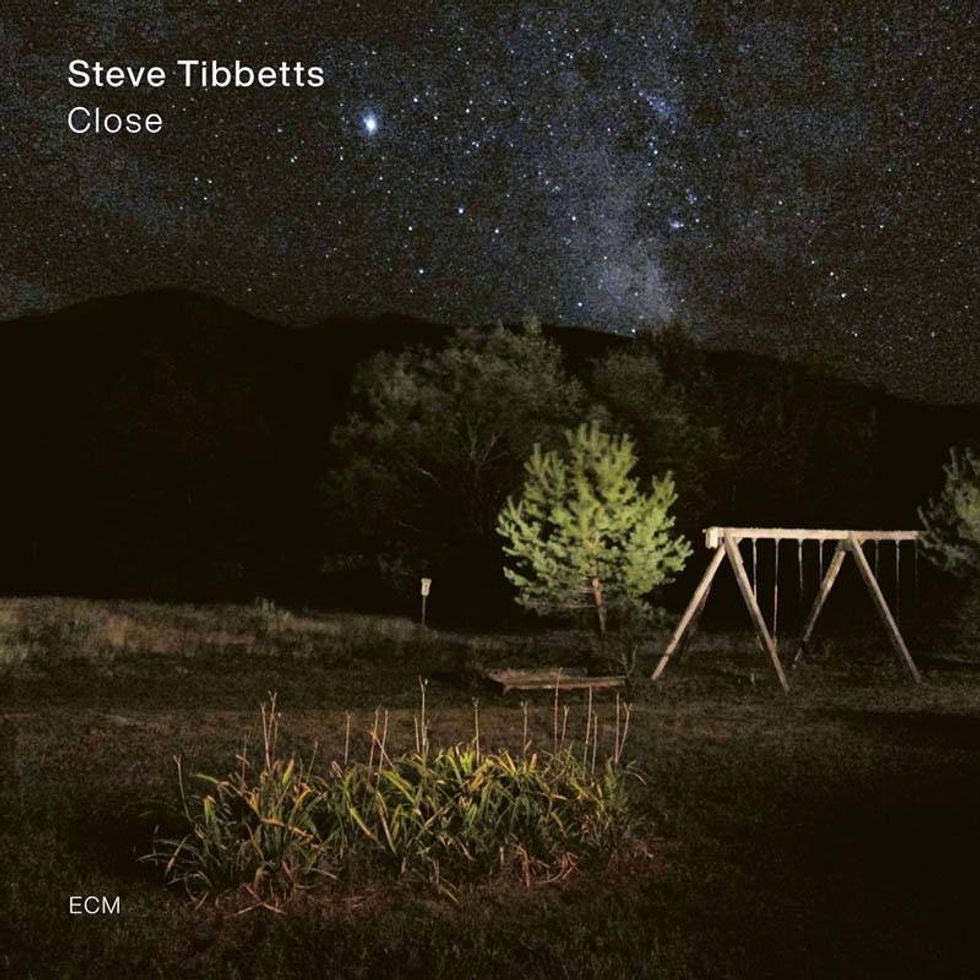

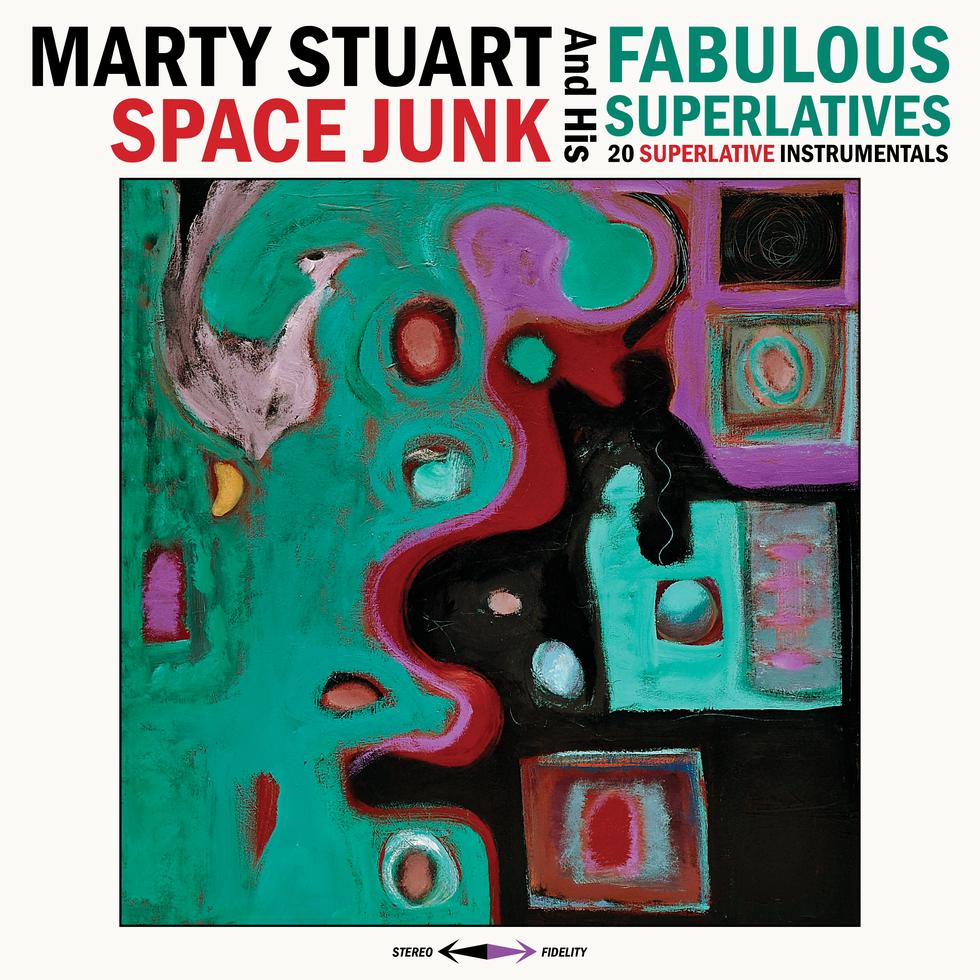

On his first full album of instrumental songs, the new 20-tune collection Space Junk, recorded with his longtime co-conspirators the Fabulous Superlatives, Stuart shows exactly why he was never fully Nashville’s guy in the first place. “In my original record collection, there were several records by the Ventures and Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass,” Stuart says of his adventurous early musical loves, both of which left a sizable sonic imprint on Space Junk.

In the ’60s, instrumental groups were common on the charts, and Floyd Cramer’s wordless 1960 hit, “Last Date” was a mainstay in Stuart’s childhood home in Philadelphia, Mississippi, alongside the bluegrass he was devouring and quickly mastering. “Instrumentals were just part of the language that I grew up listening to,” he says.

Marty Stuart’s Gear

Guitars

1954 Fender Telecaster with B-bender (“Clarence”)

1956 Gretsch 6120

1967 Fender Kingman (Nashville tuning)

1939 Martin D-45

Amps

Fender Deluxe with power boost mod

Strings and Picks

D’Addario NYXL or Nickel Wound, various gauges (electric)

D’Addario Phosphor Bronze, various gauges (acoustic)

Fender medium tortoise shell picks

Marty Stuart and his Fabulous Superlatives: (left to right) Kenny Vaughan, Chris Scruggs, Harry Stinson, and Stuart.

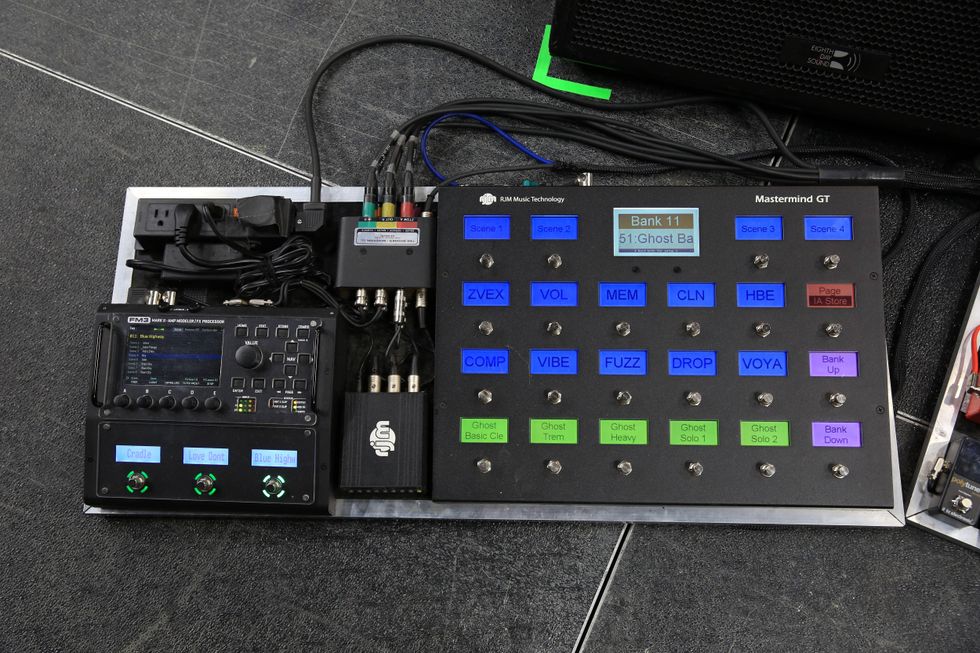

Kenny Vaughan’s Gear

Guitars

RS Guitarworks Kenny Vaughan model

Fender Mike Campbell Red Dog Telecaster

1961 Fender Jazzmaster

1999 Martin HD-28

1983 Fender Squire Stratocaster

1993 Rickenbacker 360/12V64

Amps

Fender Princeton

Marshall JMP PA20

“The minute I stepped out of chasing one record or one style of record down two streets in Nashville and got back into being a world-class musical citizen rather than just being a hit-chasing hillbilly, it opened up the sky.”

With a lifetime’s worth of musical range already percolating, Stuart entered the trade himself at age 12 as a mandolinist in the employ of bluegrass pioneer Flatt. Instrumental flair was part of the set in those days, encouraged by the marquee names themselves. “Everybody knew that Johnny Cash was a star and Lester was a star, but there was a turn every night where everybody had their moment,” Stuart says. He took the experience as training, and the Superlatives—guitarist Kenny Vaughan, multi-instrumentalist Chris Scruggs and drummer Harry Stinson—have carried on the tradition from day one. “Everybody can step up and run the show without breaking a sweat, and it spoils me to pieces to have people like that around me.”

Stuart has made a habit of being an enthusiastic collaborator. When his solo recording career took off with his 1989 album, Hillbilly Rock, the first in a three-album run of Gold-certified records, he followed it by co-writing the Grammy-winning “The Whiskey Ain’t Workin,’” which he and Tritt recorded together in 1991. The duo repeated the trick on “This One’s Gonna Hurt You (For a Long, Long Time)” the next year.

But after pursuing hits, Stuart aimed for another level of expression and storytelling with The Pilgrim, an ambitious concept album built around a love-triangle narrative. While the project was one of his least commercially successful endeavors, it marked the arrival of a new regimen for Stuart. “The minute I stepped out of chasing one record or one style of record down two streets in Nashville [a reference to the city’s home of industry, Music Row] and got back into being a world-class musical citizen rather than just being a hit-chasing hillbilly, it opened up the sky,” he says.

What pulled him out of the morass was scoring All the Pretty Horses, the 2000 film adaptation of the Cormac McCarthy novel, which he credits with teaching him about painting without words. “The visual and the sonic worlds have to dance together,” he says. “It all comes down to whether it moves somebody or it doesn’t. It comes from the heart or it doesn't.”

“The visual and the sonic world have to dance together,” Stuart says. “It all comes down to whether it either moves somebody or it doesn’t. It comes from the heart or it doesn’t.”

When Stuart assembled the Fabulous Superlatives to back him on the 2003 album Country Music, he found the band that could fully express his vision of a boundless group rooted in country but willing to explore the outer limits of their sonic tapestry. To wit, Space Junk wasn’t conceived in a conventional series of studio sessions. Rather, it shows how deeply down the rabbit hole the band members were willing to go from the jump.

“We really didn’t set out to write an instrumental record,” Stuart explains. “We just kept making up songs that made us smile and we enjoyed playing on stage. It turned us back into kids with our first Fender guitars, and that’s the truth.”

The songs on Space Junk predate both 2023’s cosmic country-rock Altitude—recorded after backing the Sweetheart of the Rodeo 50th anniversary tour with the Byrds’ Chris Hillman and Roger McGuinn—and 2017’s trippy, high-desert hallucination Way Out West. Informed by his childhood influences, many of which he shares with his bandmates in the Fabulous Superlatives, Space Junk cracks open the cinematic sweep of Stuart’s musical universe.

Opening the album with a reverb-rattled surf lick, “The Graveyard” begins the immersion into the group’s interplanetary soundscape. Stuart gets out further with the mindbending leads on “Bat Patrol” and pulls high drama into the wide-open Western skies of “All the Pretty Horses.”

“I get up and see what [the guitar] has to say that day, and it’s always wonderful to learn a new lick or a new chord that actually works somewhere,” he says. “Songs are what bring those things about easily for me.”

“We just kept making up songs that made us smile and we enjoyed playing on stage. It turned us back into kids with our first Fender guitars.”

All the members of the Fabulous Superlatives contributed to the compositions on Space Junk.

The Vaughan-penned tunes “The Surfing Cowboy” and “The Ballad of the Lonely Surfer” are opposite sides of the same coin. Although both are rooted in Ventures-style surf music, the latter is built around a tremulous chord progression and melody while the former is an upbeat tune with bright, Byrdsian passages bookending leads by Vaughan and Stuart, who played a 1967 Fender Kingman in Nashville tuning. Stinson and Scruggs also contributed songs to the project, with Scruggs playing the prominent pedal steel on closer “Waltz of the Waves” and lead guitar on “Slipnote Serenade,” both of which he wrote, and Stinson writing and arranging strings on the title track.

“The thing I admire about this record is that it’s really melodic in a world where there’s a thousand notes a minute flying at you from the hottest guitar players in the world,” Stuart says. “And trust me, everybody on this bandstand can slay you with 1,000 notes a minute. But something that shows a lot of wisdom and a lot of maturity as a player is air, and there’s a lot of air on this record, and the melodies are hummable.”

Irony is a certified guitar slinger who owns a vast collection of country-music artifacts but only keeps “a couple of acoustics” at his home, like the pre-war Martin D-28 with “a real skinny neck that sounds like a cannon” that Stuart often picks up. His only amplified rig around the house isn’t even for a guitar. It’s a Buck Trent electric banjo and Sho-Bud amplifier.

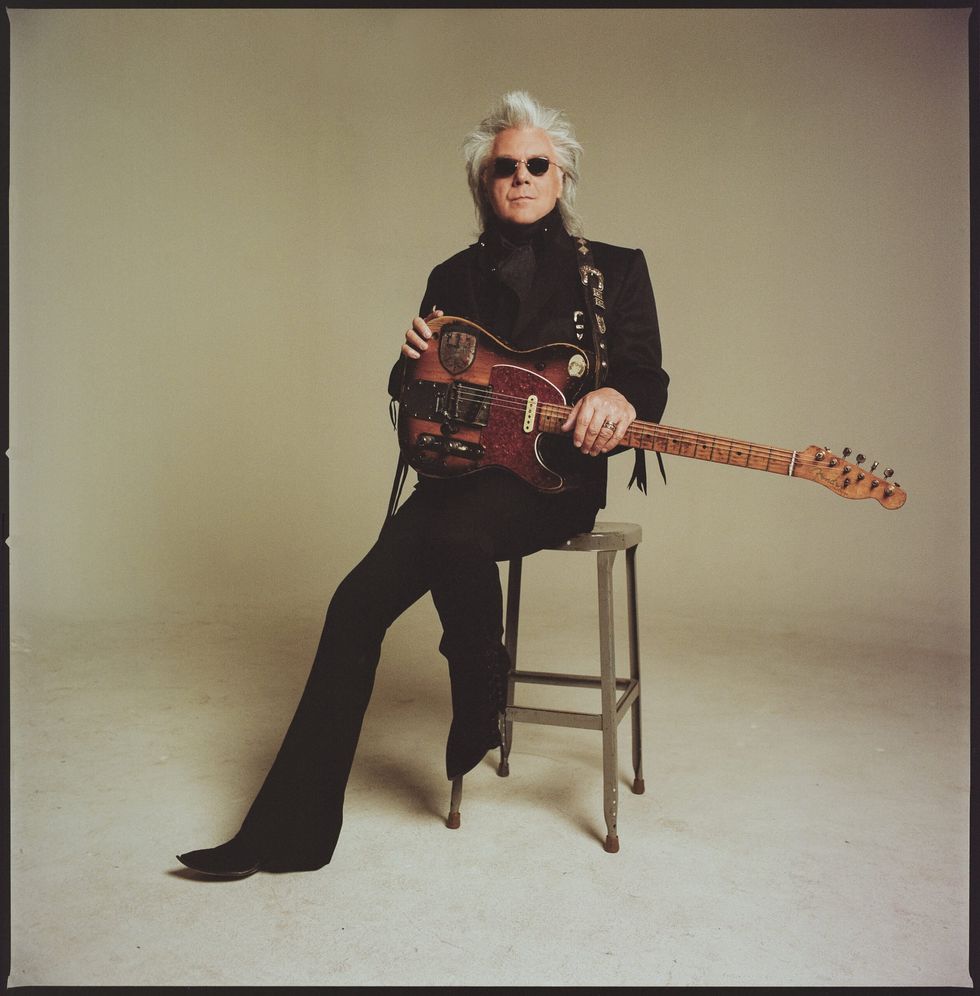

Among his storied collection are Johnny Cash’s personal gloss-black Martin D-35, A.P. Carter’s 1936 Martin 000-28, a rosewood Fender Telecaster owned by Pops Staples and given to Stuart by daughters Mavis and Yvonne Staples, and guitars that once belonged to Carl Perkins, Charley Pride, and Merle Haggard. But while Stuart, one of Nashville’s great sidemen-turned-stars, may own an army of guitars, he only used a handful of his workhorses to make Space Junk. Arguably, the most historic guitar he owns is the one most associated with him now, the 1954 Fender Telecaster modified by Gene Parsons and Clarence White with the first B-bender.

“Every time I pick it up, there’s something to learn,” he says, “and that guitar still knows a hell of a lot more about me than I know about it. But I love playing it; I love the sound of it. I love the way it feels. But to tell you the truth, every time I think I’ve really got something going on, I hear some tape or some record that Clarence played on. Then, ‘No, back to the woodshed.’ It’s amazing to think that he died when he was 29 years old and he really had it on the run.”

Stuart also used a 1958 Gretsch 6120 hollowbody and a 1939 Martin D-45 to complement Vaughan’s RS Guitarworks signature model, a 1983 Squier Strat, a ’61 Jazzmaster, and a Mike Campbell signature model Telecaster.

“My rig is as straight ahead as Willie Nelson’s rig or Bill Monroe’s mandolin,” Stuart says. “I have a silverface Deluxe amp, and it has a power boost on it and an EQ that I couldn’t operate if my life depended on it.” For Stuart, the magic is in the guitars themselves. “If you plug that Clarence White guitar into any amp on planet Earth, it’s still gonna sound great. If you plug that Gretsch 6120 into any amp on planet Earth, it’s still gonna sound great. My sound is those guitars.”

Now in his sixth decade as a professional musician, his formerly black mane a shock of textured grays, Stuart is still reliably inclined to zag when the industry zigs. Having a band of virtuoso players on his side helps when he’s ready to make his next move.

“Being a part of this band, there’s nowhere they can’t go, legitimately,” he says. “If you can think it up, it can get played here. It makes the world a whole lot more interesting.”

YouTube It

Marty Stuart and Kenny Vaughan tear it up in a vintage appearance on Late Night with David Letterman.

Kenny Vaughan—Stuart’s 6-String Foil

Stuart and his guitar foil, the highly respected and versatile Kenny Vaughan.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

Longtime Superlative sideman Kenny Vaughan isn’t your typical country guy who geeked on the Nashville sound as a kid. But on exploratory records like Space Junk, where versatility and imagination are part of the gig, his background has been a boon.

“I grew up listening to jazz [and took lessons from Bill Frisell], and then I got into Frank Zappa records and all kinds of stuff that has nothing to do with country music,” he says. Yet, Vaughan developed a soft spot for honky-tonk tunes during his childhood in the late ’50s and early ’60s. “I’ll never forget the first time I heard Ernest Tubb. My head exploded. I was like, ‘This guy is from outer space.’”

By the time he picked up a guitar, the AM radio airwaves were awash in instrumental music. “They would always play an instrumental right before the news report at the top of the hour, so you’d hear ‘Rumble’ by Link Wray or ‘Walk Don’t Run’ by the Ventures,” he says. His first performance was a neighborhood recitation of surf tunes with other local kids, and later, when he formed a band of his own, they would open shows with the Ventures’ “Cruel Sea.”

Vaughan took his own circuitous route to Nashville, arriving in 1990 just as the hat acts—superstars like Garth Brooks and Alan Jackson—rose to prominence. He eventually found his place in the rowdier rooms of Lower Broadway and toured with Lucinda Williams before hooking up with Stuart in 2002. For more than two decades now, Vaughan and his Fabulous Superlatives bandmates have built up a mutual trust working within Stuart’s expansive musical landscape.

“Everybody in the band brings a lifetime of in-the-studio experience to the table, so when we work up tunes it’s pretty easy to fall into playing the right parts,” he says. “Every song is different, and rarely will we use the same starting point.”

The songs on Space Junk are a case study in how the group functions. All four musicians contributed songs and collaborated across its 20 tracks, and no one was uptight about taking cues from the others. On a few occasions, when Vaughan dialed up the “stratosphere tuning” made famous by Jimmy Bryant—a 12-string-specific configuration in which the doubling strings are tuned up a third instead of an octave—Stuart, with his encyclopedic knowledge of country-music instrumentation, was there to help guide his parts.

“Marty helped me work out the solos, because none of the notes were where they’re supposed to be,” he says. “When you play that tuning, you have to relearn the neck and compose your solo. I’d sit in the control room, and he’s sitting right next to me and saying, ‘No, play this.’ It was done on the fly, but he kind of produced me.”

Challenges sometimes came from his own tunes, like “Malibu Dawn,” which uses polychords. “I heard it in my head,” he says, “and I took a couple of days to work it out to where I could present it to the guys and walk them through the whole idea.” The band learned and mastered the tune, then put it on tape. “Some tracks play themselves, and boom, it’s done,” he says. “Others take a lot of work.”