Whenever you hear country blues-inflected guitar played through an amp with tremolo, you’re hearing a sound descended from singer/composer/guitarist Pops Staples. Best known as the leader of a family gospel group, the Staple Singers, his guitar style influenced and inspired John Fogerty, Bonnie Raitt, Ry Cooder, and countless others. The dark mystery of his instrument’s wavy sound has become part of the fabric of American music.

Roebuck Staples, known as “Pops,” was born to Warren and Florence Staples on December 28, 1914, on a cotton plantation near Winona, Mississippi. Roebuck and his older brother Sears were named after the Chicago mail-order company that supplied millions of rural Americans with everything from washing machines to musical instruments.

The Staples soon moved to a plot on the Dockery plantation near Drew, Mississippi. As a teenager, Staples would make money participating in local boxing contests, but other interests had already begun. Though secular music was forbidden in his family, his brother David played blues guitar. By age 14 Staples was paying fifty cents a week towards a Stella he saw hanging in a store window. Like many blues artists of the time he picked cotton during the day, but when work was done he’d commune with the guitar, taking it to bed and playing under the covers as long as his father would allow.

—Leroy Crume

In Drew, he heard blues legend Charley Patton, who played at a local hardware store in the evenings. The sight of Patton, Howlin’ Wolf, and others making a living playing music inspired the young Staples to practice. By age 16 his diligence paid off with party gigs on the plantation circuit. The house manager collected contributions from the attendees, sometimes paying the guitarist $5 a night—a fortune by sharecropper standards.

Despite his love of the blues, Staples remained involved in the religious community, singing in church and later touring with a gospel quartet, the Golden Trumpets. At the time the guitar was associated with “the Devil’s music” and forbidden in churches, though Staples never saw the contradiction—he felt the blues were just telling a different story.

Citified

At 18, Staples married 16-year-old Oceola Ware. A daughter, Cleotha, and a son, Pervis, soon followed. Seeing no future for his family in the South, he journeyed to Chicago. There, Staples put the guitar down for a dozen years while working in a slaughterhouse and a series of other jobs. Oceola worked as well, and gave birth to two more daughters: Yvonne and Mavis.

The Staple Singers pose with Don Cornelius (right) on the set of Soul Train. This publicity photo was taken during production of the June 8, 1974 episode.

Chicago in the ’40s was a hotbed of R&B, blues, and bebop. The Staples family lived in the neighborhood that spawned such talents as Lou Rawls, Sam Cooke, and Johnny Taylor. Gospel was also on the rise, with guitar-based male quartets and piano-accompanied female soloists working a circuit of churches around the nation.

For a while, Staples joined the Trumpet Jubilees as a vocalist, but in 1948 he decided to form a group closer to home. He pulled out an old guitar and taught Mavis, Cleotha, Pervis, and Yvonne harmony parts to “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” The family’s debut at an aunt’s church brought seven dollars and promises of more gigs. The Staples warm Southern sound quickly caught on, and soon they were branching out to other cities and states.

In 1950 Staples bought his first electric guitar, an amp, and the tremolo effect that would help define his sound. Pops played a variety of mostly Fender guitars throughout his career: Telecasters, Jazzmasters, Jaguars, and Stratocasters. In Greg Kot’s book, I'll Take You There: Mavis Staples, the Staple Singers and the March Up Freedom's Highway, Sam Cooke’s guitarist Leroy Crume recalled: “When Pops came on the scene, he brought this little gadget you put on an amplifier—at the time they weren’t making amps with tremolos … People used to call it ‘Pop Staples and his nervous guitar.’” The effect was most likely a DeArmond 601 Tremolo unit, which became available in 1948.

Though Pops Staples never left the church, he’d spent his fair share of time in juke joints playing the blues. With his family band committed to gospel, he now joined a Baptist church and was “born again,” giving up secular music for the moment.

In 1953, Pops had the newly named Staple Singers record a single to sell at shows. A Chicago label, United Records, soon signed them, but their first label record, “Won’t You Sit Down (Sit Down Servant),” failed to hit. An early version of “This May Be the Last Time” (later covered by The Rolling Stones as “The Last Time”) was cut but not released until years later, and on another label. United wanted the band to move in a more rock ’n’ roll direction, and for Mavis to sing the blues. Pops refused to agree.

It was back to the factory for a while, but the Staple Singers’ singular sound—14-year-old Mavis’ low voice, Pops’ falsetto, and country soul in an urban environment—couldn’t be denied. Another part of their unique appeal was Staples’ guitar. Though artists like Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Pops’ favorite, Blind Willie Johnson, had incorporated guitar into gospel, the Staple Singers were one of the first Chicago gospel groups to employ this previously shunned instrument. They were allowed to enter local churches that had previously permitted only keyboard accompaniment.

Vee-Jay Days

In 1955, the Staple Singers’ worth was recognized by Vee-Jay records (who later recognized the Beatles’ talent, distributing their records in America when Capitol initially refused). After a couple of false starts, they released the haunting “Uncloudy Day.” It became the Staple Singers’ first hit (at least by gospel standards) and allowed them to begin touring nationally.

Part of the Staples’ appeal lay in a down-home sound and attitude that reminded Northern urban churchgoers of their rural Southern roots. The Staples’ stripped-down performances—just Pops’ guitar and their voices—stood in stark contrast to the more flamboyant gospel acts of the day.

Pops’ playing is the foundation of the tracks the Staple Singers cut for Vee-Jay between 1955 and 1961. As Greg Kot describes it in his Staples book: “His style created an atmosphere that was immediately distinctive, a hypnotic swirl of reverb, repetition, and riff. Chords were implied as much as articulated, notes were blurred, tones and overtones were carefully layered like the bricks Pops used to cement into place at his construction jobs.”

While the Staple Singers’ repertoire wasn’t strictly gospel, identifying themselves with that genre gave them an advantage over R&B groups: They could play hundreds of small churches across the country, sometimes doing two or three services a day at a single church. Like many R&B artists, though, Staples carried a gun in his briefcase to ensure payment by crooked promoters and to protect the money afterwards.

In the 1960s, the Staple Singers moved to Orrin Keepnews’ jazz and folk label, Riverside Records. Keepnews added more prominent bass and drums to their recordings, helping them extend their audience beyond the church while remaining true to their homespun roots.

The group managed to fit into the “folk” music revolution of the ’60s, often crossing paths with Bob Dylan on TV shows and at festivals. The fledgling legend was a huge fan—to the point of asking Mavis to marry him. The group recorded “Blowing in the Wind” for Riverside before Dylan’s own version hit the streets.

Pops often found folk music’s message to be in tune with his family’s ideology. Dylan’s music, and a meeting with Martin Luther King, Jr., inspired him to record songs reflecting the civil rights and anti-war movements for their record This Land.

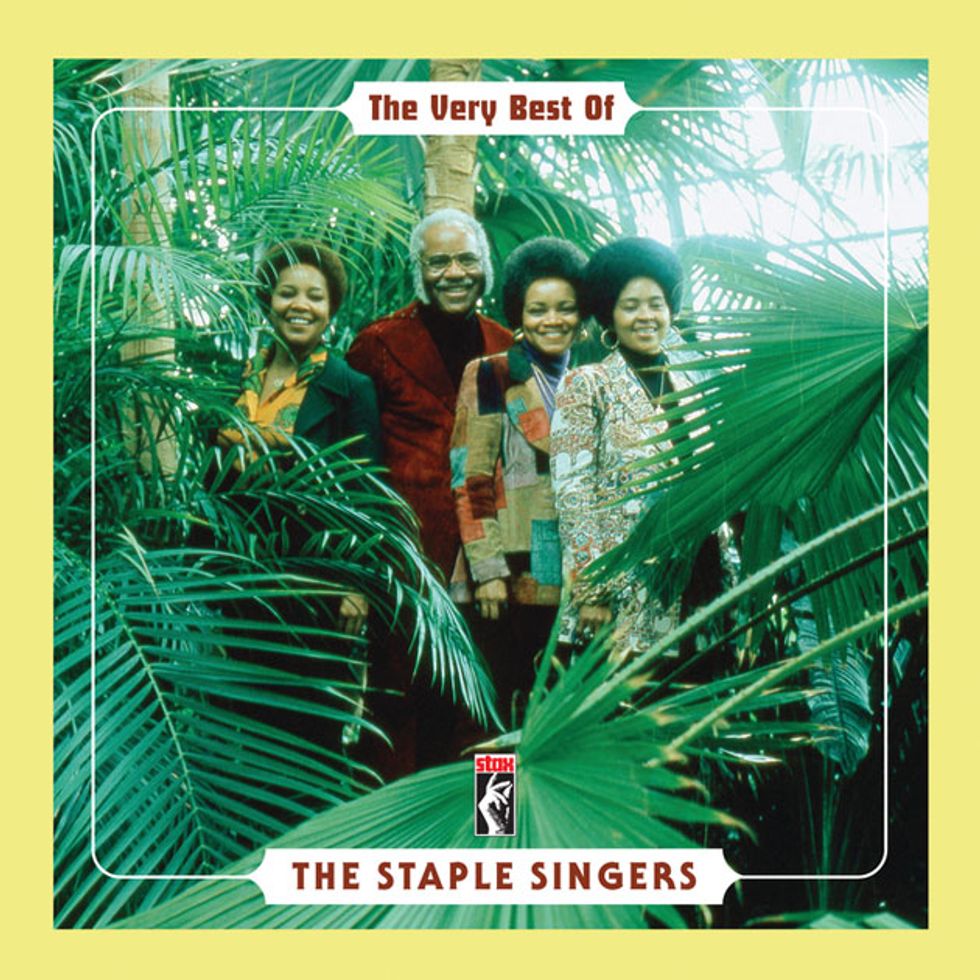

Cleotha, Yvonne, and Mavis Staples (left to right) are the female vocalists of the Staples Singers. The first song their father, Pops Staples, taught them to sing harmony on was “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”

Freedom Highway

In 1965, the Staples signed with Epic and recorded with producer Billy Sherrill. Sherrill was known for creating the “countrypolitan” sound of artists like George Jones and Tammy Wynette, but had started in music playing the blues.

That year also brought the famous Selma to Montgomery civil rights march. Pops Staples, upset by the images of clubs, dogs, and tear gas, was moved to write his iconic song “Freedom Highway.” The group performed it for the first time at Chicago’s New Nazareth Church, where Sherrill recorded the entire performance for the live Freedom Highway record. Al Duncan on drums and Phil Upchurch on bass add admirable support, but Pops’ guitar anchors the recording, from the country blues licks of “When I’m Gone,” to the rockabilly rhythm/lead combo of “He’s All Right.” By the concert’s end, the Staple Singers had defined the meeting place of the African-American church and the American civil rights movement.

The Staples were devastated by the death of their friend and hero Martin Luther King in April 1968, but by July they’d recovered enough to sign with Stax Records, where Al Bell and Steve Cropper helped them continue on their path toward gospel-infused pop music.

Bell also wanted to produce solo records for Pops and Mavis. He and drummer Al Jackson, Jr., had the idea of making a record featuring three Stax guitarists: Pops, Cropper, and Albert King. Though Pops’ tremolo guitar is overdubbed on a number of Jammed Together’s tunes, its full low-tuned mystery is reserved for the one Pops feature, “Tupelo.”

Guitarless in Muscle Shoals It wasn’t until Bell produced the Staple Singers in Muscle Shoals that the group had their first crossover hit, “Heavy Makes You Happy (Sha-Na-Boom Boom).” But it was their next one, “Respect Yourself,” that solidified the Staple Singers as crossover stars, hitting the pop charts at number 12.

For the follow-up, “I’ll Take You There,” Bell played a Jamaican record, “The Liquidator,” by the Harry J Allstars, for the Muscle Shoals crew. They lifted the intro practically intact and put their own spin on Aston and Carlton Barrett’s reggae rhythm. Though Mavis breathes, “Play, Daddy” before the guitar solo, Muscle Shoals guitarist Eddie Hinton performs it.

In Muscle Shoals Pops was not permitted to play guitar. Though the “Swampers” had utmost respect for his sound, his style was too idiosyncratic to fit into their well-oiled music machine, though the spirit of Pops’ sound remains in Barry Beckett’s spooky electric piano and the soulful guitars of Jimmie Johnson and Eddie Hinton. Pops wasn’t happy about not playing on the sessions, but his feathers were smoothed when “I’ll Take You There” became a number one pop and R&B single.

These secular successes brought some expected backlash from the gospel community, who took the Staples’ political and pop songs as a sign they were turning their backs on the church. Pops felt the group was still doing the Lord’s work by bringing messages of hope, pride, and unity to the black community. The group played a prominent role in Stax’s celebration of black pride, the 1972 Wattstax concert, and was featured on the best-selling recorded documentary that followed.

Staples’ guitar was absent on the next round of Muscle Shoals sessions as well. Despite being a retread of “I’ll Take You There,” “If You’re Ready (Come Go with Me)” gave them another top 10 hit in 1973. “Touch a Hand (Make a Friend)” followed it up the charts later that year. The album, Be What You Are, also contained a track called “Heaven,” featuring acoustic and electric guitar (and a solo) from another Staples fan: Jimmy Page.

The Weight Part II The Staples left a failing Stax Records in 1975, but were quickly signed by Warner Brothers, who paired the group with Curtis Mayfield as producer. Mayfield was working on a soundtrack for Let’s Do It Again, a movie featuring Bill Cosby and Sidney Poitier, and wanted the Staples to sing the title song. Initially put off by its sexual innuendo, Pops was brought around by his respect for Mayfield and his daughters’ enthusiasm, leading to yet another huge hit.

In 1976 Martin Scorsese convened a special shooting session of the Staple Singers and the Band singing “The Weight.” The Staples had covered the song back in 1968, weeks after the Band’s first album, Music from Big Pink, was released. The group had been unable to play the concert filmed for the Last Waltz, but the Band considered the Staples’ vocal sound a huge influence on their own vocals and harmonies, and wanted them in the movie.

The late ’70s saw many bands struggling with the rise of disco, and the Staple Singers—now simply known as the Staples—were likewise caught in the conundrum. Chasing trends with tunes like “Let’s Go to the Disco” was no answer. They returned to Muscle Shoals in 1978 in hopes of recapturing some of their original magic, but cutting a bunch of dance tracks, even with the Swampers, was no help.

Working in Allen Toussaint’s studio with Meters bassist George Porter and arranger Wardell Quezergue also failed to reignite the Staples’ success. In 1984, on yet another label, the Staples had a new flirtation with the R&B charts thanks to a recording of the Talking Heads tune “Slippery People.” This led to Pops acting in Talking Heads frontman David Byrne’s movie True Stories. Other acting jobs followed: Barry Levinson’s film Wag the Dog and the Chicago production of Bob Telson’s gospel-based musical, The Gospel at Colonus. Finally, Mavis left the group for a solo career, and Pops began his own solo flight.

The Staple Singers with Stax label mates Booker T. & the MG’s in a late 1960s rehearsal.

Solo Staples Virgin Records subsidiary Point Blank was signing a spate of blues artists in the late ’80s, including Albert Collins and John Lee Hooker. At the behest of Hooker’s booking agent, they signed Pops.

Peace to the Neighborhood let Staples bring his guitar to the fore once more on tunes like “I Shall Not be Moved,” “Miss Cocaine,” “Down in Mississippi,” and “World in Motion.” With guest artists Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, and Ry Cooder helping out, the record earned a Grammy nomination in 1992. Pops’ tremoloed guitar appears on about half the Point Blank follow-up, Father Father, which, despite a lack of blues tunes, won the 1994 Best Contemporary Blues Album Grammy.

Pops’ career slowed, but the awards continued. In 1998 Staples was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and in 1999 the Staple Singers were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The following year, on December 19, 2000, Pops Staples died after suffering a concussion in a fall near his home in Dalton, Illinois, just nine days before his 86th birthday.

Despite failing health, in 1998 Pops had begun sessions for another solo record. Shortly before he died, the ailing musician asked Mavis to play him the unfinished tracks. When they were done, he pleaded to his daughter, “Don’t lose this.” That became the album’s title when it was finally released in 2015. Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, who has produced acclaimed records for Mavis, reworked the music, stripping away most of the original session tracks, leaving Pops’ signature guitar, vocals from Pops, Cleotha, and Mavis, and a few tasteful overdubs.

Don’t Lose This serves as a fitting finale for Roebuck “Pops” Staples, the man who brought the sound of electrified country blues guitar to the church, the city, and the world.

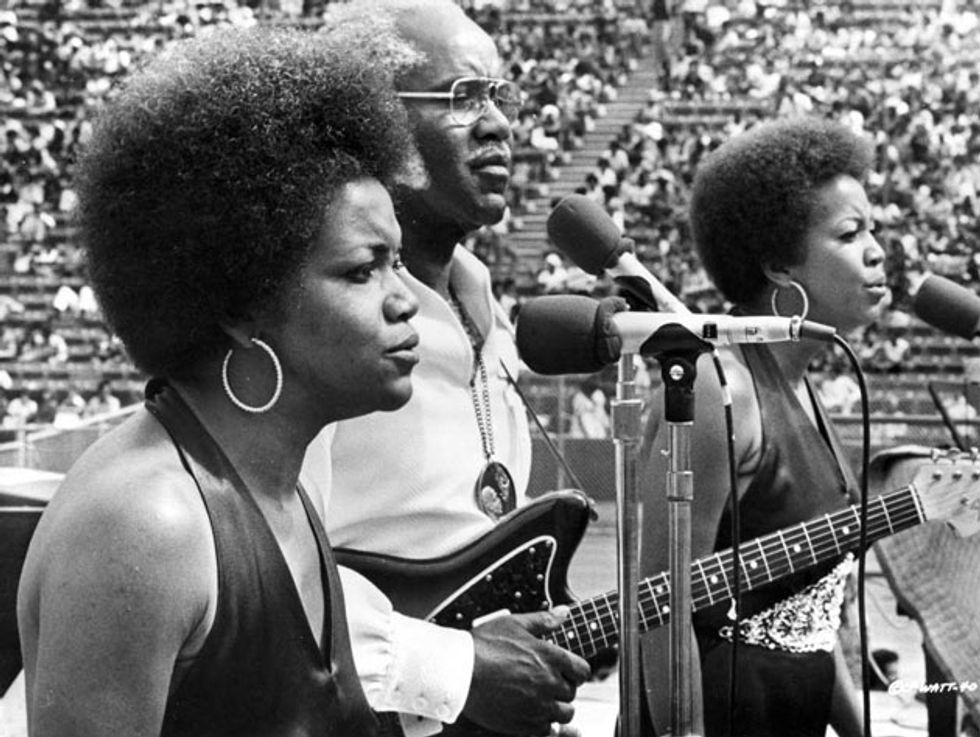

Pops Staples plays his Jazzmaster onstage with the Staple Singers circa July 1971.

Hallmarks of Style: Pops Staples’ Guitar

Pops Staples’ deceptively simple guitar style seamlessly combined strumming with bass lines and picked melody notes, all rendered with a vibe-heavy groove.When bluesman Rick Holmstrom took the job as Mavis Staples’ guitarist, he brought the spirit of Pops’ without feeling the need to be a carbon copy. Mavis was onboard with that, deriving new inspiration from his personal approach. Nevertheless, Holmstrom has studied the gospel patriarch’s style in great detail.

“Watch him on videos, where he’s playing E7 in root or ‘cowboy’ position,” says Holmstrom. “He may be tuned down to D and capoed up to Eb, depending on the time period, so I took one of my Teles and tuned it down a whole step—it gets the spookiness down there. Pops would take that first position E chord and pick out little melodies with his pinky on the high E and B strings He might also be doing a hammer-on on the D string from D to E,or from Ato B on the A string. Sometimes he would slide up to the root on the A string. He might have had an alternating thumb bass going on the low strings, but it was not strict like with country guitar.

“You can hear Charlie Patton, Son House, and Big Bill Broonzy in his playing. People have laughed at me when I say he reminds me a little bit of Scotty Moore, but he was not all blues. On ‘Suzie Q,’ James Burton plays that E7 chord with a little lick, and it sounds like something Pops would’ve done. Pops wasn’t any kind of great technician, but he had this great vibe.”

For Marty Stuart, seeing Pops Staples play in The Last Waltz was revelatory. “After that, I became enamored of the Vee-Jay recordings,” he says. “I have always been a fan of a guitarist who can take two notes and wreck you.”

Stuart met Staples when working with the Staple Singers on the Rhythm Country and Blues record, and was quickly adopted by the family. When Pops died, Mavis and Yvonne gave the country star the rosewood Fender Telecaster Pops played in The Last Waltz. Stuart has compared it to being handed Excalibur.

“It’s an instrument of light and truth,” says Stuart. “When I put that guitar on, there is a responsibility that falls around my neck. I left it tuned down to Eb, the way Pops played it.”

The guitar started off with standard Telecaster pickups but, according to Stuart’s co-guitarist, Kenny Vaughan, was later modified with a Fender Wide Range Humbucker and 6-way brass saddles.

“It’s real heavy—one of the solid ones,” says Stuart. “I’ve tried to play country and rock on that guitar, and it won’t come out. But as soon as I play gospel, it comes to life.”

Stuart recalls one time when Pops visited Nashville. “Pops called and said, ‘Marty, I need two things: a Fender ’65 with a shake on it and a stretch-out car.’ I said, ‘No problem,’ and then I called Mavis and asked, ‘What is a Fender ’65 with shake on it and a stretch-out car?’ She said, ‘Oh Marty, that’s a Fender amp with tremolo and a limousine.’ [Laughs.]”

Stuart beautifully summarizes the elusive magic of Pops’ playing: “It’s like trying to tell somebody about the Grand Canyon if they’ve never been there, or explain a dream you had last night. Sometimes when you can’t analyze something, the best thing to do is to shut up and let it entertain and inspire you.”

YouTube It

In this rare clip from 1968, Pops accompanies his daughters on the gospel classic “Wade in the Water” with only a Fender Jaguar. The song is associated with the Underground Railroad.

The Staples Singers “I’ll Take You There” was the number one hit in 1972 when this TV performance was filmed.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.