|  |

This month, we sat down with five small builders— Bill Crook, Chihoe Hahn, Rick Kelly, Ron Kirn and Jay Monterose—who all specialize in Tele-style guitars, and asked them about their approach to building and just what separates their guitars from the rest. And even though Tele-style guitars are fairly straightforward in nature, we found five different answers, each with their own dream of the ideal Tele-style guitar. So whether you’re looking for an “art-quality” instrument to call your number one, or you just need another Tele to fill out your closet, we’re betting you’ll find a builder here to call.

Hit Page 2 for the first of our five builders...

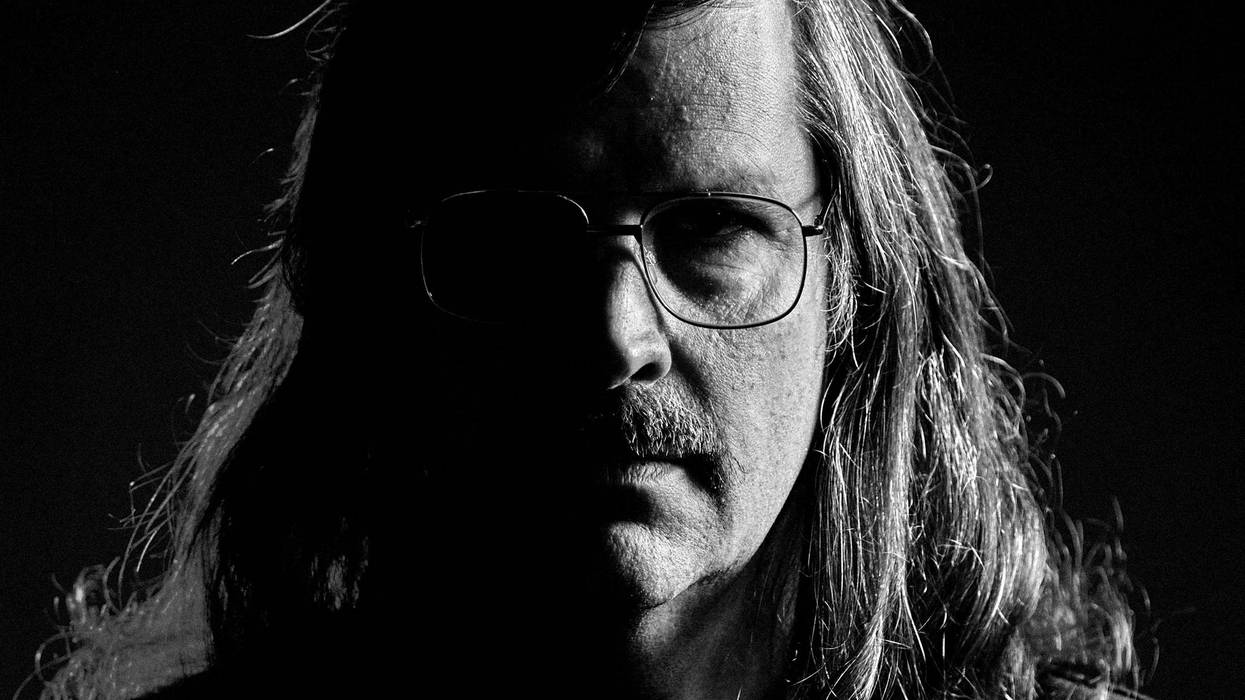

Ron Kirn

Ron Kirn Signature Guitars

| |

|

It really began back in the mid-sixties. I started as a teenager, and like everybody, fell in love with the guitar. This was back in the days of Elvis and the Ventures and the early Beatles, etc. Of course I wanted a guitar, so my father bought me an early Silvertone, which was a horrible guitar. And I’ve always had a mechanical aptitude, so I immediately attacked that thing, trying to rectify it. And I learned quite a bit about guitars from that.

Tell us a little bit about your philosophy.

I just build them the way I think they should be built. They’re either playable or not playable, to me. I just take it all the way through to the final end, and I play it—in fact, I’ve got two of them sitting here behind my desk right now that I finished a couple of days ago. What I’ll do is I’ll finish them, string them up and intonate them, and then I’ll let them sit there and just get used to being under tension, because the wood will shift. Then I’ll fine-tune them from there. For some reason, people seem to appreciate that type of thing—go figure.

What do you love about the Telecaster?

It’s really hard to say. To me, it’s kind of like you find a mutt and everybody puts it down because it’s not an American Kennel Club registered dog—but it turns out to be your best friend. And that’s kind of the way I felt about the Telecaster. The simplicity, the concept of less-is-more kind of slaps you in the face. You don’t need 14 pickups and a monster whammy bar and all of these controls.

Do you offer customers a set model or configuration?

No, I build custom guitars, and I tend not to dissuade potential clients from what they want. I understand the psychology behind a choice of a guitar.

Most people are led to a specific guitar by someone within their circle of influence who will persuade them of what they need to have. So if your best buddy walks up to you and says that you’ve got to have a Telecaster that’s Shell Pink with an alder body and a rosewood neck, and it’s gotta have Fralin pickups and a Callaham bridge and a fourway switch in it, that settles in your mind because it’s been reinforced by your association and the dependability of the source that suggested it to you.

If you walk up to a luthier and he says, “No, man, you don’t want Shell Pink or an alder body. What you need is swamp ash, oh, and Fralins suck—you need to use Owen Duff’s pickups. And that rosewood fingerboard looks like crap on there.” And you also appreciate this guy, because, one, you’ve chosen him, and two, he does this for a living, so you immediately assign value to his input and you allow him to persuade you from what you originally wanted from your guitar.

And you go out, and you now have a guitar, and you show it to your friend, and he says, “Well, that’s cool, but it would have sounded better with an alder body.” And you’re out gigging and playing your favorite song,

and in the back of your mind, you always have that thought, “Did I make the wrong choice?” Any kind of little thing like that will gnaw away at you until eventually it erodes your confidence in the instrument, and you make it your number two, you sell it, whatever. Whereas, on the other side of the coin, if you walk up to me and you tell me what you want to do, and I say, “No problem; let’s do it,” and you say, “What do you think about that sort of thing,” I’ll say, “It’s great.”

and in the back of your mind, you always have that thought, “Did I make the wrong choice?” Any kind of little thing like that will gnaw away at you until eventually it erodes your confidence in the instrument, and you make it your number two, you sell it, whatever. Whereas, on the other side of the coin, if you walk up to me and you tell me what you want to do, and I say, “No problem; let’s do it,” and you say, “What do you think about that sort of thing,” I’ll say, “It’s great.”I understand you build guitars with reclaimed lumber?

I try, people tend to like it. Let me tell you about this lumber—the buildings were built in 1600, but they used the lumber from previous buildings that were built roughly 100 years earlier, the historians say. Which means that they were built by the first French settlers to hit that area in 1500. So I’ve still got enough for about four or five of those guitars. It’s fascinating to work with that stuff; when you cut a piece off, you pick it up and ask yourself, “Is there anything else I can make with this?” It makes for an incredible sounding guitar. For somebody who’s not really into the tone psyche and that sort of thing… I don’t know if it’s my subconscious telling me that I need to hear a great sound out of this guitar, but the few guys that have bought these things tell me that they’re blown away by the sound. But it might just be working on their heads, too.

Why should someone buy a Ron Kirn guitar?

Well, for the cost, you can’t touch it. That’s it in a nutshell. It’s literally like being able to buy a Ferrari for what a Crown Vic costs.

Hit Page 3 for the second of our five builders...

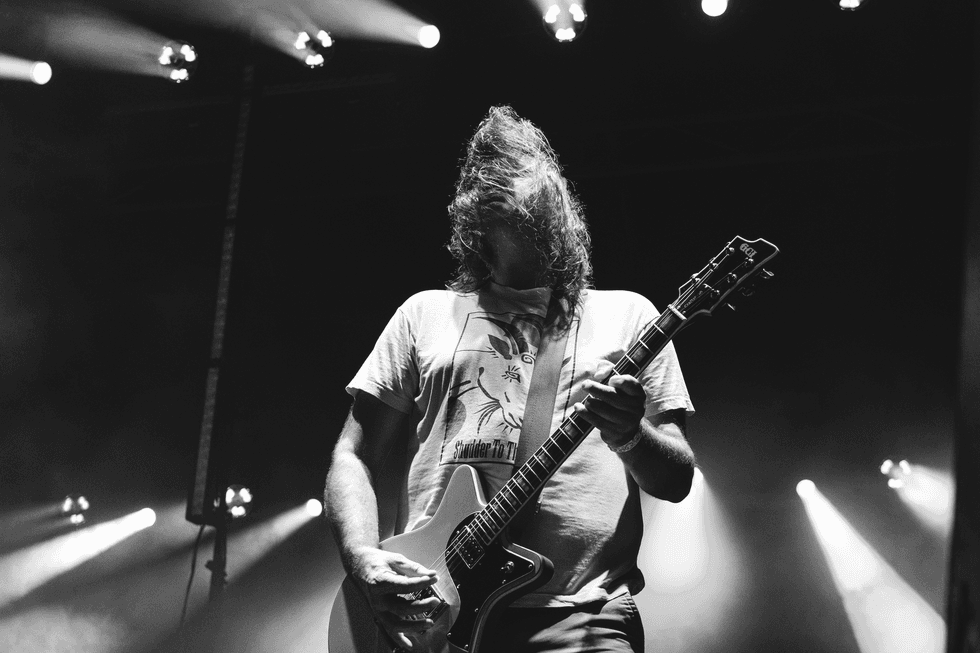

Chihoe Hahn

Hahn Guitars

| |

|

I got into it trying to get a guitar that I liked. I was searching for a tone that I just couldn’t find by buying new guitars and looking around at used guitars, so I just started making my own.

Has the Telecaster always been a favorite design of yours?

Yeah, I’ve played Teles since I was a kid, for no other reason than that’s what was around. [laughs] I’ve always loved that clean Fender tone, and that’s just sort of what I started with, and eventually I fell in love with.

Do you have a particular model of Tele or Esquire that you look to for inspiration?

It’s really early to late-fifties Tele-style—I’d say up to ’59. And that’s the inspiration; the one thing that I like to say is that I like to be as inspired in the execution as Leo was in the design. It’s probably the most basic design in a guitar that you can have. You can’t even break it down beyond how it has been broken down. So that is really what I try to stay true to: the absolute simplicity of the design. And I sort of stay away from anything that is either ornate or tone-sucking. I just keep it as plain as it can be.

That sounds like a very stripped down building philosophy.

When you buy something today, you sort of look at it and you inspect it for any imperfection, and if you find any imperfection, you sort of summarily reject it—I think that’s generally how things are today. And that gives people a sense of quality, perfection in the execution. And what I try to do in the guitars, my aesthetic goal, is to straddle the line between manufacturing perfection and “handmade.” So that the person can get the sense of superior quality, but it retains that human element.

What is your flagship model?

The model that I offer is called the 228. And it’s, again, inspired by a fifties Telecaster. There are variations on that that I do; I do swamp ash, alder, and I’m working on mahogany bodied guitars now. But it’s all built off the 228 platform.

You fabricate most of your hardware in-house, correct?

Yeah, the bridges, the saddles, all of the knobs, the neck plate and the control plate.

Does the fact that you’re making all of these components yourself give you a different perspective on the building of these guitars?

I don’t think so; they’re really just tools. A friend just showed me a Glendale bridge, and I was blown away by it, period. So I called up Dale and I’m talking to him about working to fabricate some stuff for me. Because, to me, the hardware is like the pickups—it’s a tone shaper, it allows you to achieve something with the guitar. So I talk to the customer, I usually ask for favorite guitars, for favorite songs, for audio clips to get inspiration from the customer. And from there, we talk about it and decide what the hardware and pickup choices are going to be. And that’s the starting point, but then you actually build the guitar, and then you’ve got something, usually an X factor that you couldn’t have anticipated, and you can even tweak it from there. So I do a lot of my own parts, but it’s just one choice that’s available for the customer.

Is there a go-to pickup that you use in your guitars?

I’d say there are go-to manufacturers that I’ve used, and I certainly don’t mean to say that some are superior, but I’ve worked a lot with Lollar, Fralin and Duncan.

What brings you back to those builders?

What brings you back to those builders?I like the way that Jason achieves specific things with specific pickups. They’re very dialed in to what it is he’s trying to achieve, and they do it really well. I think Fralin— they all sound amazing, but I love the flexibility, the versatility of his pickups. And I love the balance of the Duncan pickups. What makes your guitars unique? When you’re dealing with small builders, you could put all of the guitars up against each other, and they’re all going to be radically different. I think it’s just that there are 100 decisions to be made in making any guitar, and they all add up to more than the parts. I’d say if there’s one thing, it depends on the ear of the builder and the aesthetic of the builder which flows through every one of those 100 decisions.

Why should our readers consider buying a Hahn?

I think people will find it to be an extremely musical instrument. It’s made to be extremely dynamic and articulate, but primarily musical. The notes are articulate, but it’s a seamless blend between strings and as a whole. It’s as much a rhythm guitar as a lead guitar.

Hit Page 4 for the third of our five builders...

Rick Kelly

Kelly Custom Guitars

| |

|

Right after college—I majored in sculpture in college—I started with Appalachian dulcimers in the late sixties, early seventies, and then I converted over to guitars; I started electric guitars probably around 1972.

When did you first discover the Telecaster?

That was actually because of a guy down in Maryland named Dimitri Callas. He was an awful lot like Roy Buchanan—a family man. He was asked by the Stones if he would play with them, and he said, “No, I have to stay here with my family,” kind of like Roy did. He had a bunch of old fifties Teles, and he had me make him a couple of bodies. That was in about 1975, and so that’s when I started working with Teles.

What is your flagship model?

I’ve pretty much been making ‘52 Tele-style guitars since the early seventies, and I make them very much to Dimitri’s ‘53 Tele specs. So I make a very traditional Telecaster, but I have a new design now where the horn on one side is actually lopped off, and it follows the curves of Leo Fender’s custom Telecaster pickguard that had that short curve to it. I sort of made the horn match that curve—it’s very Leo Fender-esque. And I use the paddlehead stock on it, which also matches the Fender’s prototype.

What makes your guitars unique?

The thing I do differently is I use wood that’s over 100 years old. I’ve been collecting reclaimed lumber since the early seventies, when I lived down in Maryland. I was out every Sunday at farm auctions; I’d get greatgranddad’s wood that was in the barn that no one really bid on, and I wound up stockpiling a lot of old wood. Today it’s a lot easier to find old timber—there are a lot of reclaimed lumber businesses out there now that will just sell it to you. But there’s no reason to use new wood, which is inferior to old wood, when it comes to guitar building. You need to have the resins crystallize in the wood, so it becomes more resonant. That’s the main difference in my guitars—the age of the wood and the resonance of the guitar.

Lately I’ve been using wood from an old street here in the city that’s called the Bowery; it’s one of the oldest blocks in Manhattan, the early lower Manhattan. The buildings go back to the 1850s, and I just recently got a whole load of 1865 white pine from [filmmaker] Jim Jarmusch’s building, which was what the original Telecasters were made from. This is all oldgrowth Adirondack pine that has some amazing grain patterns—it’s so tight and extremely resonant. And it’s all roof rafters, which means that the wood was up there under black tar for 140 years, cooking all day and cooling at night, so it’s got this alchemy thing going on. It makes an amazing guitar.

How would you describe your building philosophy? You mentioned earlier that you kind of stick to a very traditional design.

Yeah, that’s really my whole thing. I spent many years building guitars that were unusual in design, and I think I have some pretty amazing designs, too, but that just kind of faded away—people don’t ask for those guitars anymore. They’re really looking for more traditional guitars, and I sort of found a niche in Fender-style guitars made from old wood. It’s what people want me to make them, and it’s what I seem to be most popular for.

What kind of hardware do you use?

That’s another thing I do differently from a lot of companies: I use individual makers. Take pickups, for instance; I use only people who just make pickups, not companies that make guitars as well. Right now I’ve been using a lot of Don Mare pickups; we’ve actually been doing some

trading of guitar parts.

trading of guitar parts.What do you like about the Don Mare pickups?

They’re handmade, and it’s one guy making them, and he really concentrates on using the best materials. And he captured something about that original fifties tone that no one seems to be able to have gotten. I use Lindy Fralins also—he and Lindy are very similar in that respect. They capture that fifties vibe.

What about the rest of the hardware on your instruments?

I try to stick with Klusons for tuning machines because they’re traditional. And there are guys that make amazing bridges for Telecasters—Glendale makes a great bridge and a beautiful set of saddles that interconnect. They’re amazing sounding and they perform perfectly. Leo made a perfect guitar, and it’s really hard to make it any better, but nowadays people have been coming up with individual components that really do make it a little bit better.

Why should our readers consider buying a Kelly?

Well, I think they’re going to get the individuality of a true custom guitar. What they call custom shops today aren’t really—they’re just pulling pieces off a factory line. This is a custom shop: one guy from start to finish.

Hit Page 5 for the fourth of our five builders...

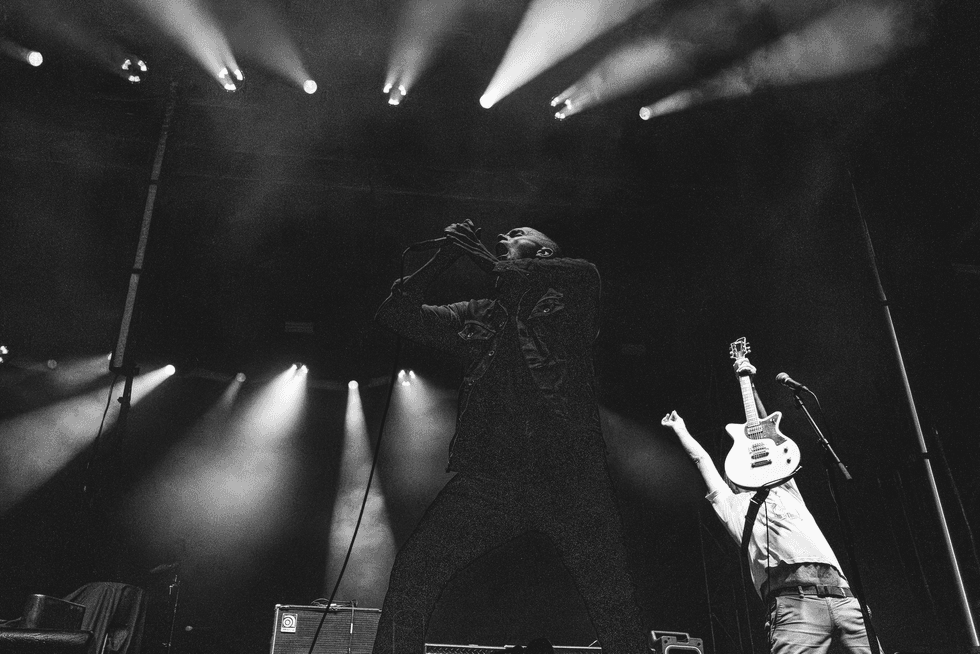

Bill Crook

Crook Custom Guitars

| |

|

Well, I’m 50 years old. Growing up around here as a kid, music stores were more worried about saxophones and violins than electric guitars. And my dad was one of those guys who, if your roof leaked, you climbed up there and fixed it; so when my guitar didn’t work, I figured out how to fix it. And I buggered up a bunch of them and went from there.

How do you approach the building of a Tele-style guitar? What’s your philosophy?

I love the looks of the past. It’s a timeless look and feel—and that tone! But for a lot of modern players there are some shortcomings that vintage instruments have. So I try to keep a lot of the looks and classic vibe, but I try to make them a little more user-friendly for modern players.

What do you mean by making them more user-friendly?

Some simple stuff, like compensated saddles and compound radiuses. Growing up, something that always drove me crazy with old Teles was trying to intonate them. And with a vintage radius, you were always hindered in how low you could get your high E string and bend it—of course, if you grew up on them, you didn’t know any better and you thought it was okay.

What would you call your flagship model?

Well, everything is built to order, so there really is no flagship model. But the basic model, if there was one, would be the 9.5 compound radius neck that I use a lot, with a very traditional bridge made by Callaham. I use those almost exclusively unless somebody’s looking for something different.

Who do you think is making the best Tele pickups right now?

You know, for the neck pickup, my favorite is the Adder Plus neck pickup; it’s a small company out of the Chicago, Illinois area, and I’ve used them for years, and they’re just a great pickup. My favorite bridge pickup is made by Peter Florance of Voodoo Pickups.

What do you hear in those pickups that you’re not hearing anywhere else?

There’s a richness in the midrange. It’ll be clean when it’s supposed to, but, like a good pickup should, when you dig in you’ll hear more harmonics and growl out of it. You know when you pick one up, and you’ve got an amp just sitting there on the edge, and you dig in and it gets big and fat? That’s what Peter’s pickup does for me in the bridge.

What makes your guitars unique?

A lot of it is the attention to detail. The final neck shaping I do by hand; I roll the edges of my necks because I want them to feel like a pair of shoes you’ve owned for years. I want it to be comfortable. The way I finish my necks is a little different, but again, it feels like old lacquer that you’ve played— it doesn’t feel sticky or glossy. I spend a lot of time on the fretwork, the nutwork, just going over the details.

My necks are held on with threaded steel inserts and machine bolts, as opposed to wood screws. I really like what it does for the sound of the guitar; it helps with the resonance and the sustain. And I build a lot of guitars that use string benders; guys are pushing down on that, and that’s anywhere from 16 to 22 foot pounds of pressure they’re applying. So besides the neck fitting in the pocket tight, it just keeps everything much more foolproof.

A lot of people know you for your paisley guitars; how did those come about?

A lot of people know you for your paisley guitars; how did those come about?It’s funny; I had never thought about doing them until Brad [Paisley] got his record deal—I’ve known him since he was a little kid. Myself and couple of friends of mine threw our money together, and I got the parts to build him a guitar as a congratulations present. He said that he really liked the [guitar] that I had previously built him, but he was wondering if I could do paisley. So I started researching it, and I knew that the originals had been done with a papertype covering, so I looked everywhere I could, on the internet, wallpaper stores. But even when I could find it, it looked like something from someone’s grandmother’s den. So this went on for a couple of years, and I ended up hooking up with a graphic artist. And we figured out how to do it, but it was an ongoing process of being able to get a print that looked like something— finding the right kinds of ink. Some of the first ones I sprayed—I didn’t know any better— I was using a lacquer-based sealer, and I watched the ink run right off when the lacquer hit it.

Who should be playing your guitars?

Ideally, a guitar player that wants to just play, and not fight the guitar, in terms of playability. Because ultimately you’re there to make music, and the guitar is just a tool to do that. And there’s nothing worse than trying to make music when you’ve got to worry about things like intonation.

Hit Page 6 for the last of our five builders...

Jay Monterose

Vintique

| |

|

Absolutely not. I did the same thing that Danny [Gatton] did; I was playing Gibsons for years before I got to the Telecaster thing. The Telecaster thing started in the D.C. area because Roy Buchanan was playing. And nobody had ever heard anybody do that with a Tele before, so it opened up a lot of our heads about what you could actually do with that guitar.

So we started playing those guitars, and then we discovered their shortcomings. There’s a lot of great attributes to the’ 53 Tele. It’s odd to think that the first production guitar would end up being the best platform all of these years out, but we didn’t like the fact that you couldn’t get the guitar to intonate. The bridge plate was floating on the guitar; there was enough space to slip your business card under the front of it, and with the bridge plate not making full contact with the body, it would oscillate, causing the pickup to feedback and squeal. So we knew that was kind of screwed up. Also, the necks would loosen and shift in the pocket, causing string misalignment.

What did you do to address problems with the neck pocket?

In the process of addressing this, and the other shortcomings, we ended up creating a new paradigm in solidbody guitar construction. We designed, engineered and produced high-quality hardware based on this theory of mechanical connection. With repeated removal of the neck for adjustments and service, the wood screw holes would strip out, allowing the neck to shift. We came up with a system where we drill and tap the hard rock maple and install carbon steel threaded anchors. We also replaced the wood screws with stainless steel machine threaded screws. Our choice of hardware allowed us to retain the vintage look, but without the neck shift. And with the neck drawn down under maximum compression, the result is unparalleled resonance and sustain.

How did you apply the concepts to the rest of the hardware?

The saddles are made of the best material—no cheap stuff here—and I actually invented the vintage-style barrels that intonate perfectly. With the bridge we started with a special alloy that enhances tonal characteristics and sits flat on the body, transferring maximum string energy and sustain. Because of the special alloy we use, our bridge does not affect the sensitive magnetic flux field of the pickups; the pickup sees only the vibrating strings.The hardware is machined, not stamped. I make every piece by hand personally—I consider it a real art. Others have tried and failed to match my quality of craft or tone, but it all starts in my hands.

Why aren’t more guys doing it your way?

Mass producers can’t do it my way. The handmade quality comes from being a true craftsman and artist. I have total command of my skills and tools. Most guitar guys don’t have the same expertise, knowledge and creative ideas. The ones that do can’t execute it in the same way. We’re all unique in our talents; I happen to be a player and a builder. I’ve never understood builders who can’t play on a professional level or push the envelope of their designs. Necessity is the mother of invention; Danny Gatton and I had to build our own Tele-style guitars because there wasn’t anything commercially available at the time that met the demands of our playing, and our pursuit of perfection.

What is your flagship model?

I make total art-style guitars called the DG5394 and 5394. I’ve spent years refining them to be the finest handmade Tele-style guitars available anywhere, handmade with premium old-growth wood completely by me. Other than the fretwire, tuners and stainless screws, we manufacture everything else—from an exact replica of a ’53 Tele body to handmade Charlie Christian pickups. All of the patterns, templates and fixtures are based on my Tadio Gomez ’53 Esquire and are dimensionally accurate to .020”. You can’t tweak them any further!

What kind of pickups are you using in the 5394?

The two basic options available are the “vintage- style” handwound single coils spun on Danny Gatton’s homemade pickup winding machine that he had wound on since 1967. He even showed Seymour Duncan how he wound flatpole Broadcaster pickups on this unit back in the day! This also includes the “Chuck Christian” models on the DG5394. For the hi-fi humbucking freaks, we incorporate the “rocket science” d

esigns of pickup giants Bill and Becky Lawrence.

esigns of pickup giants Bill and Becky Lawrence.Who are you guitars meant for?

Vintique guitars are for anyone who loves the fifties-style Teles, but requires a no-holds-barred platform to execute the highest order of functionality in this type of instrument. It’s as versatile as the artist playing it. Tele giants from James Burton to The Hellecasters use our hardware, and Danny Gatton, Bill Kirtchen and Jim Weider have played the guitars as well. Vintique is also currently building guitars for Vince Gill and jam band king Steve Kimock.

Some people have raked you over the coals for fulfillment problems and lengthy waits. Is that fair?

Thanks for asking that! The music business and industry as a whole can be tough. It’s not easy to be an artist making music or to achieve a high art in manufacturing. Unless you have a golden horseshoe buried where it counts, it’s a labor of love. I’ve been dragged about with promises and been taken advantage of, and unfortunately some of my clients have had to endure the lows with me. The good news is that this year my pal Steve at Angela Instruments will be distributing our hardware, and I’ll have guitars at Gothic City Guitars as well.

Carondelet Introduces OTB Ultimates Vintage-Style PAF Pickups

Carondelet Introduces OTB Ultimates Vintage-Style PAF Pickups