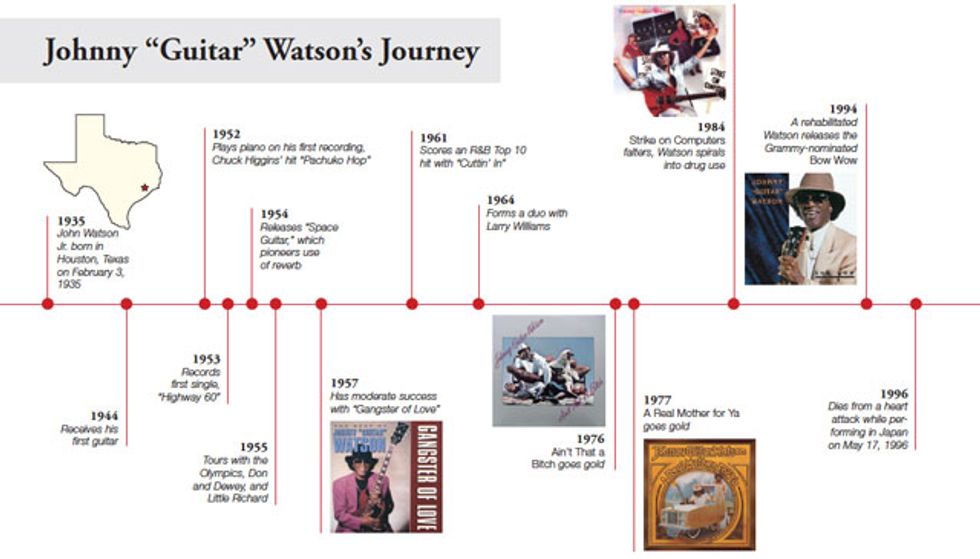

Born: February 3, 1935

Died: May 17, 1996

Best Known For: A pioneer and innovator of blues, R&B, and electric funk guitar, Watson influenced a wide range of players—from Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, and Stevie Ray Vaughan to vocal legends like Etta James.

It seems odd to call someone whose soulful guitar work and flamboyant showmanship influenced artists as diverse (and acclaimed) as Etta James, Frank Zappa, Prince, and Rick James a “forgotten hero.” But, unfortunately, Johnny “Guitar” Watson never achieved the level of fame that those he inspired did—a point that is painfully underscored by the fact that he’s occasionally confused with “Wah- Wah” Watson (also a wonderful player who deserves praise). Johnny “Guitar” Watson had a groundbreaking—if up-and-down— career that spanned five decades of American popular music. A career that included everything from a Grammy nomination to having his drug problem spotlighted on VH1’s Behind the Music.

T Is for Texas

On February 3, 1935, Wilma Watson

gave birth to John Watson Jr. in Houston,

Texas. His father, John Sr., played piano as

a part-time job, and ended up teaching the

instrument to his son. At age 11, Watson’s

gospel-playing grandfather offered him an

acoustic guitar if he promised he wouldn’t

play “the devil’s music”—meaning blues

and R&B. Whether or not he ever intended

to keep that promise, under the spell of fellow

Texans T-Bone Walker, Lowell Fulson,

and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Watson

soon broke it. In the liner notes for The

Very Best of Johnny “Guitar” Watson, David

Ritz quotes Watson as saying, “T-Bone had

all the flash and fire, which I wanted.”

Unsatisfied with the volume of his flattop, Watson claimed he stole an early DeArmond pickup and screwed it under the strings. The pickup’s cable screwed on to both pickup and amplifier, hampering his early performance style. Or, as he put it, “If you try to go anywhere, you better bring everything with you.”

By age 12, Watson secured a record contract, thanks to the help of DJ and R&B legend Johnny Otis. In what would become a pattern when it came to label relations, the tween musician bucked the higher-ups by refusing to record children’s songs, and was soon dropped. But Watson remained undiscouraged. By his teens, he was gigging with Texas bluesmen Albert Collins and Johnny Copeland.

In 1950, John Sr. and Wilma separated. Wilma took young John Jr. to Los Angeles, where he soon won several talent shows and was discovered by Amos Milburn and Chuck Higgins. Watson’s first recording experience came as a 17-year-old pianist playing on Higgins’ hit “Pachuko Hop.” On the single’s flip side, he made his vocal debut with “Motorhead Baby.” He would re-record the latter a year later, when he had his own record deal.

On January 20, 1953, two weeks before his 18th birthday, Young John Watson (as he was then billed) recorded his first single for Federal Records. He was backed by Amos Milburn’s band on a tune called “Highway 60.” The next year he recorded the seminal single “Space Guitar.” Often cited as pioneering the use of feedback and reverb, there is, in fact, no feedback on the record. However, the engineer did randomly crank the studio reverb settings on this Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown-style jump blues instrumental, giving it a unique, spaced-out feel. In 1996, Watson told Goldmine magazine: “Reverb had just come out. Everybody really didn’t understand what it was all about, man, and I was experimenting with it.” Though the record has become a classic and a collector’s item, the world was not yet ready for it. “Space Guitar” was just one more failed single for Federal, and the label soon dropped Watson’s contract.

“Guitar” Man

In the ’50s, Modern Records was home

to B.B. King and Etta James. In 1954, its

legendary A&R director, Joe Bihari, went

to the movies with Watson to catch Johnny

Guitar, a Nicholas Ray Western starring

Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden. The

movie inspired the Los Angeles guitarist to

modify his own stage name. “It sounded

like sort of an outlaw or gangster name, but

he was a good guy, like Lone Ranger, you

dig?” he told interviewer Jas Obrecht.

Modern had started a blues subsidiary in Los Angeles called RPM. Bihari and his brother signed the newly dubbed Johnny “Guitar” Watson to the label, and in 1955 he gave them a hit with his cover of Earl King’s “Those Lonely, Lonely Nights.” The E% tune opens with an unaccompanied B% guitar arpeggio, played at the first fret with a raw electric tone that must have been either a revelation or heresy in the mid ’50s. The solo consists almost entirely of one note: screaming E% triplets hammered home over the 12/8 ballad groove. It’s no wonder a 16-year-old Frank Zappa had his mind blown. “He worked that one note to death,” Zappa told Obrecht in 1982. “If you were playing the rhythm-and-blues circuit, you had to learn to play that solo note-for-note.”

Watson took off on tour with Eddie Jones, aka “Guitar Slim,” learning the art of showmanship from the man who inspired Jimi Hendrix. The two guitarists would ride on each other’s shoulders out into the audience, trailing 30-foot cords. On the Chitlin’ Circuit, playing behind your back and with your teeth was part of the two players’ performances a dozen years before Hendrix introduced these tricks to young white audiences.

Bihari’s experimentation with then-new double-tracking studio techniques allowed Watson to play both guitar and piano on sides like “Someone Cares for Me,” “Ruben,” and “Three Hours Past Midnight.” The latter is a stunning slow-blues guitar workout based on B.B. King’s 1951 interpretation of the Lowell Fulson tune “3 O’Clock Blues.” Watson’s use of his thumb instead of a pick gives the notes a snappier sound than King’s plectrum-driven style, while his “ice-pick” tone also lent the record a very different mood than the smoother King version. This side also enticed Zappa, who reportedly played the song three times a day on the jukebox at a local restaurant during his school lunch hour.

In 1955, once again without a record deal, Watson performed on package tours with all the stars of the day, including Sam Cooke, B.B. King, Louis Jordan, Little Richard, Jackie Wilson, the Shirelles, Ben E. King, and the Coasters.

A Gangster Is Born

In 1957, Watson went into the studio for

Keen Records to rework a piano-and-vocal

demo called “Love Bandit” that he had

recorded while at Modern Records. The

resulting full-band version became “Gangster

of Love.” Though sometimes touted as an

early “rap” record—not the least by Watson

himself—“Gangster” was more in the tradition

of talking R&B as practiced by Louis

Jordan and the Coasters. It was the beginning

of an image makeover that would in later

years evolve into early “gangsta,” decked out

in “bling” and “pimpin’ the hos.” Once again

Watson’s work proved more influential than

lucrative. Though the song was not a hit at

the time, it has been covered a lot since then.

A version appears on a pre-Columbia Records

Johnny Winter recording, but it was the one

on Steve Miller’s Sailor that finally earned the

struggling Texan some serious money.

As he engaged in more label-hopping for the next few years, Watson cut “Looking Back” in 1961 for Escort Records. That tune would be covered in England by both John Mayall—who credited Watson—and Spencer Davis, who didn’t. In 1961, thanks again to Johnny Otis, Watson ended up at Syd Nathan’s King Records, where he had an R&B Top 10 hit with a string-drenched slow blues tune called “Cuttin’ In.” His first and only full LP for King, Johnny “Guitar” Watson, packaged new material with remakes of tunes from earlier Watson records, including “Gangster of Love.” The failure of Johnny “Guitar” Watson to chart led the guitar slinger to Crown Records, where he briefly teamed up with blues legend Bobby “Blue” Bland for the rare recording 2 in Blues.

By 1963, the popularity of blues within the African American community was waning— and yet it still hadn’t fully caught on with the rock ’n’ roll generation. Watson attempted to revitalize his career in 1964 by teaming up with singer Larry Williams, who’d garnered fame with his cuts of “Bony Moronie” and “Dizzy Miss Lizzy.” They even formed a label—Jola Records (later Jowat)—whose moniker combined letters from their first names, but their first album was released in England on Decca.

Williams introduced the relatively unknown Watson to the British press and public as “Elvis Presley’s guitarist.” Having successfully sold that fairy tale, the duo implied that their joint effort, The Larry Williams Show featuring Johnny “Guitar” Watson with the Stormsville Shakers, was a live recording. It was, in fact, recorded in the studio. Veracity aside, the pair’s R&B/ rock ’n’ roll sound went over well in England, prompting the American label Okeh to sign them. Commercial success was their goal, and to that end they were determined to keep up with the times. In 1967, they added vocals to the Cannonball Adderly hit instrumental “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” which was written by Joe Zawinul and later became a hit for American pop band the Buckinghams. Williams and and Watson also recorded a cool cover of the Yardbirds’ hit “For Your Love,” and in 1968 joined with the Kaleidoscope (a band that, at one point, featured a young David Lindley) for a sitar-driven piece of soul/ psychedelia called “Nobody.”

The duo became a big hit on the British Northern Soul circuit with tunes like “Two for the Price of One” and “Too Late,” but unfortunately for 6-string fans, this style of music required putting Watson’s distinctive guitar playing on the back burner.

Finding the Funk

The early ’70s found Watson picking up

his guitar again, first as a session player for

artists like keyboardist George Duke and his

famous early idolizer Frank Zappa. Watson

also knew the Adderlys—Cannonball and

his brother Nat—because of “Mercy, Mercy,

Mercy,” and when the brothers formed their

own production company they helped their

friend get a deal with Fantasy Records in

Berkeley, California.

Left alone to produce himself, Watson began forging a sound that suited the times: a combination of blues and slow-jamstyle funk—think Barry White and Bill Withers, and you’ve got the idea. Fantasy released Listen and I Don’t Want to Be Alone, Stranger, later combining them on CD as Lone Ranger. Both albums featured a lot of great guitar playing, though it was wrapped in a veneer of smooth soul. While white audiences had by then discovered Buddy Guy and the three Kings of blues (B.B., Freddie, and Albert), and were lapping up British blues rock, Watson was trying to keep the blues relevant to African Americans by combining it with the soul and funk sounds being heard in their communities. “Just because [blues] has been presented in a way that they can’t grasp doesn’t mean the love of blues isn’t there—it is,” Watson told Rolling Stone in 1976.

At this stage of his career, the flamboyant picker’s tone shifted from switchblade sharp to a warmer, more liquid and vocallike sound. He had forsaken his ’50s Fender Stratocaster and ’60s Martin F-65 electric for Gibsons, including ES-125, Explorer, ES-335, ES-347, and (in the ’90s) SG models. He also owned Fender Telecasters and Jazzmasters, as well as a Vega acoustic.

Fantasy’s promotion of Listen left Watson wanting, leading him to hire his own independent promoter, who propelled a single from the record into the Top 20 of the R&B charts. The momentum helped his next release, I Don’t Want to Be Alone, Stranger, sell nearly half a million copies. While at Fantasy, Watson added guitar to records by trumpeters Nat Adderly and Freddie Hubbard, and used the studio time afforded him there to hone his production skills. He even got gigs producing records for Percy Mayfield and Betty Everett. By 1975, Watson was label-less again. But he was still productive, partnering with singer Lenny Williams to compose “Don’t Change Horses (In the Middle of the Stream)” for Tower of Power.

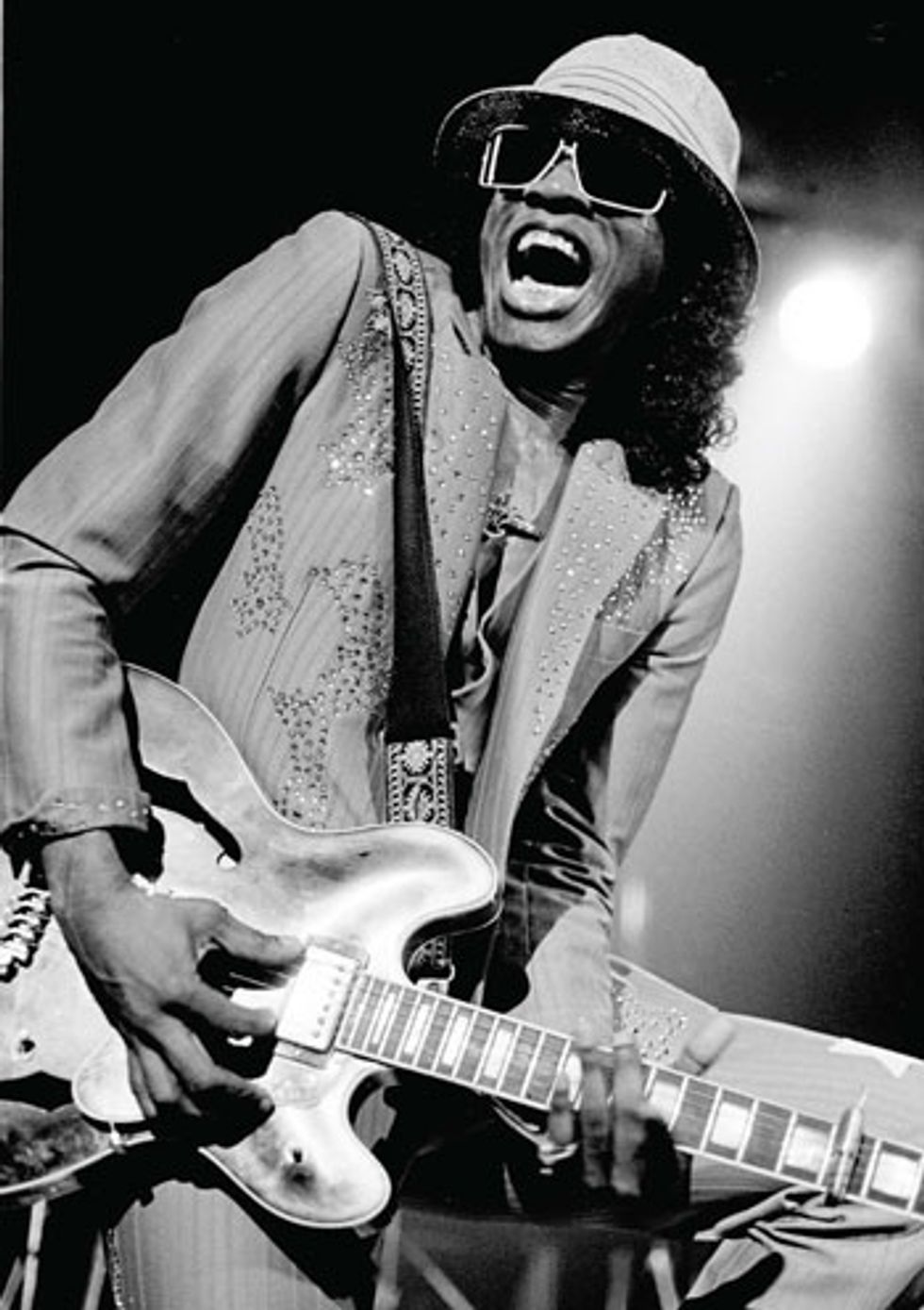

Known for flamboyant picking, Watson moved from his early ‘50s Fender Strat to playing Gibsons, including the ES-125, Explorer, ES-335, ES-347, and SGs. Photo by Klaus Hiltscher/Affendaddy

The James Gang

If English publisher Dick James’ name

sounds familiar, it is because his company,

DJM, handled copyrights for the Beatles

and Elton John in the ’60s. In 1976, legendary

British blues producer Mike Vernon

(Bluesbreakers, Fleetwood Mac) introduced

Watson to James, who promptly signed the

guitarist and gave him complete creative control.

For his DJM debut, Watson overdubbed

most of the instruments himself, save for

co-producer Emry Thomas’ drumming. The

result, Ain’t That a Bitch, went gold, and the

second stage of Watson’s career took off.

The title tune is essentially a blues number dressed up with some funk flourishes. The record also yielded “I Need It,” a dance hit on both sides of the Atlantic. At first, that tune sounds like Earth, Wind & Fire gone disco, but eventually Watson’s guitar enters to play the melody followed by a few tasteful riffs. At the time, this is how Watson explained his style to Blues and Soul Magazine: “I guess you would call it progressive R&B—almost a blues approach [to] pop music,” he said. “Superman Lover” also featured a rare wah-wah solo and became a staple of Watson’s live shows.

The 1977 follow-up, A Real Mother for Ya, also went gold. Once again, Watson played everything but drums and horns. The title tune is a real guitar workout over synth bass and drums, with just a taste of talk box thrown in. With back-to-back successes, the Watson finally put the lie to Tom Vickers’ 1977 assertion in Soul and Jazz Record magazine that he had “more gold in his teeth than on his wall.” The follow-up, Funk Beyond the Call of Duty, featured Watson wielding his Gibson Explorer on the cover. It sold respectably but failed to go gold despite solid tunes and a classic Watson solo on “Barn Door.” For “It’s a Damn Shame,” he even sang along with his solo—long before the world at large had heard of George Benson.

Next came Giant, which was ostensibly geared to the European market. It was all over the map: Disco tunes like “Tu Jours Amour” [sic] and “Guitar Disco” butt up against yet another rocking remake of “Gangster of Love” and a cover of War’s “Baby Face (She Said Do Do DoDo),” while “Miss Frisco (Queen of the Disco)” was a fantastic funk-guitar workout.

Love Jones from 1980 is remembered largely for “Telephone Bill,” a spoken-word tune that is considered to have “anticipated” rap. “Anticipated? I damn well invented it!” Watson claimed to interviewer David Ritz in a 1994 interview in the liner notes to The Funk Anthology. Guitarists may be less interested in that than in the terrific, bebop-infused licks in Watson’s outro solo—which includes a quote of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts.”

On his next effort, Johnny “Guitar” Watson and the Family Clone, the guitarist pays tribute to Sly Stone only in that he plays every instrument. The good news is that his tone is a warm and natural improvement over the previous two records, which were effects heavy, and “Rio Dreamin’” features a rare jazzy acoustic solo. The bad news is that DJM had run out of promotion money, so it was time for Watson to move on. A guest guitar spot on Herb Alpert’s Beyond record in 1980 led to a deal with Alpert’s A&M records, and the first release, That’s What Time It Is, was the first record in many years that Watson had not produced himself. The result was minimal guitar, and what there was reverted to the thin, direct sound of Love Jones.

After A&M rejected three self-produced efforts, Watson found himself without a label again. The disappointment, combined with the murders of his friends Larry Williams and Marvin Gaye, found the performer spending much of the ’80s in a downward spiral of drugs. (In his 1996 New York Times obituary on Watson’s life, Lawrence Van Gelder quoted the guitarist as saying: “I got up with the wrong people doing the wrong things.”) He managed to release the lessthan- stellar Strike on Computers for Valley Vue records in 1984, but it did little to revive his career—not to mention, the title tune was out of character for a man who had spent his life embracing new technology. Though he was still able to tour Europe, Watson virtually disappeared from the recording world for a decade. His flame was kept alive by the respect peers who covered many of his songs. Robert Cray recorded “Don’t Touch Me,” while Albert Collins and Gary Moore made “Too Tired” famous on the blues circuit. Even the French pop star Johnny Hallyday got in on the action, recording surprisingly soulful versions of “Cuttin’ In” and “Sweet Lovin’ Mama.”

The Final Bow

By 1994, Watson had gotten rid of the

“wrong people” referenced in Van Gelder’s

obit, and he cleaned himself up and started

writing again. The resulting record, Bow

Wow, was more than a return to form—

“My Funk” featured a heavily distorted

solo (a first for Watson) that was as good

as anything he ever recorded. The opening

track, “Johnny G. Is Back,” offers a killer

phased solo reminiscent of a hyper Eric

Gale, as well as the opening lyric, “Where

has he been?” Watson then answers the

question himself by name-checking Al Bell,

the famous Stax records executive. Wary of

record labels, Watson had started his own—

Wilma Records (which was named after his

mother)—and Bell had agreed to distribute

the first release, Bow Wow, through his

Bellmark imprint. Bell obviously made the

right decision: The record hit the R&B

charts and was nominated for a Grammy in

the Contemporary Blues category that year.

Recognition, and eventually money, started coming as well, including from hiphop artists who liberally sampled Watson’s music. Redman based his “Sooperman Luva” on Watson’s “Superman Lover,” and marquee artists such as Ice Cube, Eazy-E, Jay-Z, and Mary J. Blige all appropriated elements of the original gangster’s music. In classic postmodern fashion, Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre borrowed P-Funk’s adaptation of Watson’s catchphrase “Bow Wow Wow yippi-yo yippiyay” for Snoop’s hit “What’s My Name.”

The success of Bow Wow allowed the guitarist/singer/songwriter/producer to tour in style, mostly in Europe and Japan. It was on tour in Japan in May of 1996 that Johnny “Guitar” Watson died as he had lived—in performance. At the Ocean Boulevard Blues Café in Yokohama, Watson had begun singing “Superman Lover” when he collapsed with his hand to his chest. He was pronounced dead of a heart attack at 9:16 p.m. on May 17, 1996.

Watson lived to receive the prestigious Pioneer Award from the Rhythm & Blues Foundation in February of that year. It was justly deserved—John Watson Jr.’s take-no-prisoners style had indeed helped pioneer the role of electric guitar in modern pop music. But as impressive as that is, it would be unfair to his brilliance to limit his legacy to his earliest achievements. His playing continued developing until the end, and his unique take on funk still influences musicians every day.

Johnny “Guitar” Watson at a 1975 R&B festival in Frankfurt, Germany,

sharing the stage with Bo Diddley, James Booker, and Screamin’ Jay

Hawkins. Photo by Klaus Hiltscher/Affendaddy

Johnny “Guitar” Watson at a 1975 R&B festival in Frankfurt, Germany,

sharing the stage with Bo Diddley, James Booker, and Screamin’ Jay

Hawkins. Photo by Klaus Hiltscher/Affendaddy

Hallmarks of Watson's Style

One of Johnny “Guitar”

Watson’s biggest influences

on the 6-string was bluesman

Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown.

Like Brown, Watson played

with a capo (or “clamp,” as

Watson called it), moving

it up and down the neck to

change keys, allowing him

constant access to open strings.

Like B.B. King, Watson rarely

played chords in live performance,

sticking mostly to

single-note solos and fills.

Watson loved the stinging sound of Fender guitars, and when he switched to Gibsons he continued to seek that brightness. His first Gibson ES-335, nicknamed “Fred the First,” gave him some of the top end he sought, but it was the Gibson ES-347 that delivered a more Fender-like sound when he needed it. It is likely he owned the version with coil taps, as he talked about having the “filter” down for a clean sound. His later use of SGs rather than Les Pauls was doubtless due to their greater clarity and top end.

Johnny “Guitar” Watson’s style ran the gamut from sophisticated, jazz-influenced lines to blatant, crowd-pleasing showmanship. But whether smart or flashy, his playing never left the pocket. Plucking the strings with his fingers and using a capo, he generated a vocal sound in the tradition of Texas pickers like Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. The important thing to remember is to “make that guitar sing.”

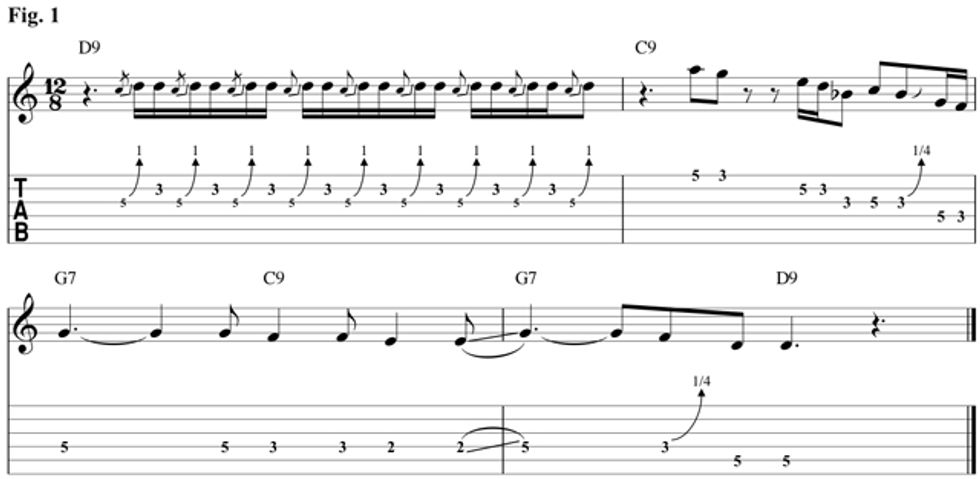

Fig. 1 shows how Watson would build tension and then release it over the turnaround in a slow blues in G. He begins with a classic Chuck Berry-esque series of 3rd-string bends before outlining all the notes of C9 in a syncopated, yet tasteful way. He finishes the last two measures with a descending line that comes to rest on the V chord, in this case D9.

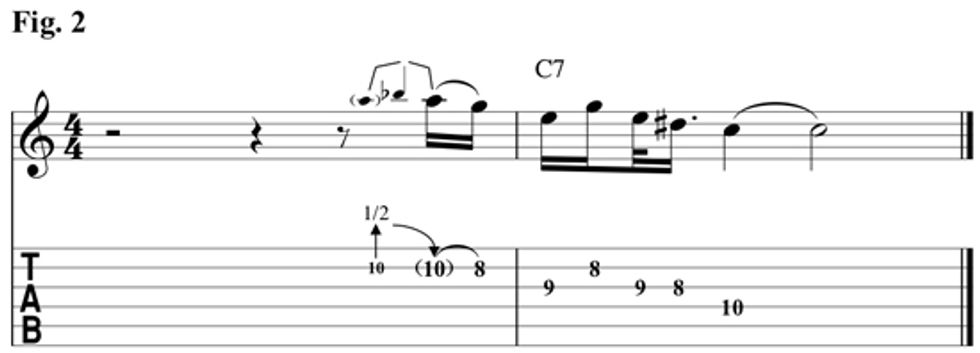

Though he could play down and dirty blues with the best of them, Watson’s phrasing often evidenced more rhythmic sophistication than the average straight shuffle licks. For the bluesy phrase in Fig. 2, Watson stays within the comfortable realms of the 8th position and emphasizes C7 chord tones (C–E–G–Bb). Playing fingerstyle makes it easier to quickly alternate between the 3rd and 2nd string in measure 2.

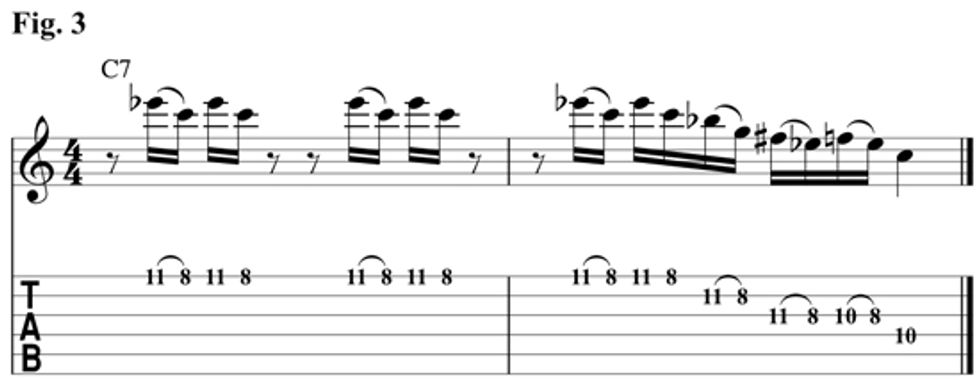

The lick in Fig. 3 stays in the C blues scale, but shifts over to a funk groove. To emulate the “snap” favored by some of the Gulf Coast players, try placing a capo at the 8th fret and playing all the 8th-fret notes as open strings. Even though the groove is fairly straight, pluck the 16th-notes with a little bit of swing to keep things moving.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.