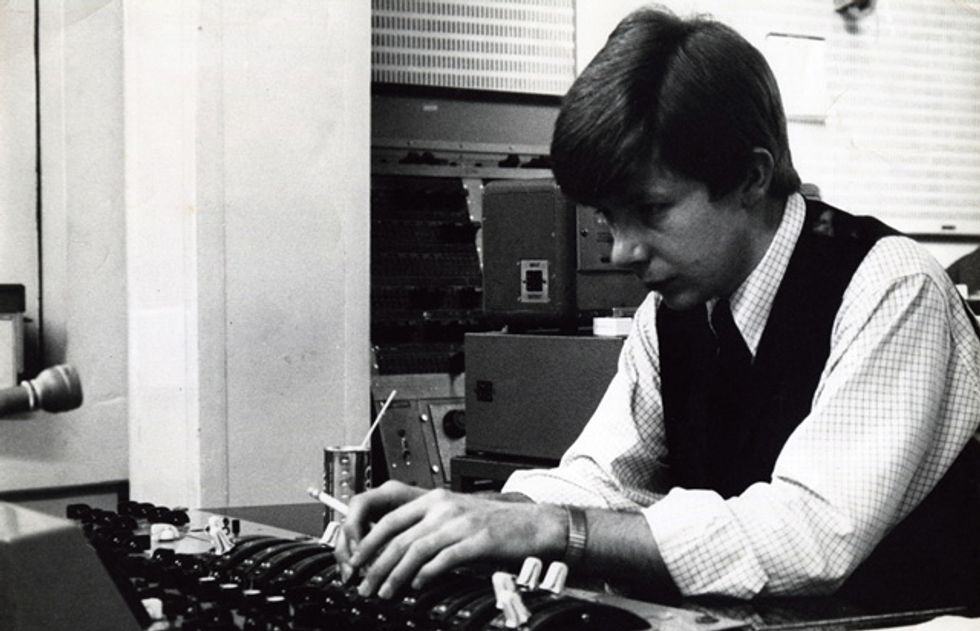

Producer Ken Scott works hard at the mixing board circa 1968 while working on the Beatles’ White

Album at Abbey Road Studios. Photo courtesy of Ken Scott

It almost sounds like a feel-good Hollywood movie: A young man gets hired by Abbey Road Studios at age 16. After moving up through the ranks, his first session as an assistant engineer is A Hard Day’s Night by an English group known as The Beatles. That same young man’s debut session as first engineer is Magical Mystery Tour. He then works on the White Album and subsequently goes on to record seminal albums with the biggest artists from the ’60s, ’70s, ‘80s, and beyond—Jeff Beck, Dixie Dregs, Supertramp, Elton John, Missing Persons, John Lennon, George Harrison, The Tubes, Stanley Clarke, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Pink Floyd, Devo, Lou Reed, Kansas, Billy Cobham, David Bowie, and many, many more. Definitely a dream career, yet also the true-life story of record producer/ recording engineer, Ken Scott.

Along the way, Scott worked with a who’s who of guitarists: Beck, Steve Morse, John McLaughlin, Tommy Bolin, Mick Ronson, David Gilmour, George Harrison, Eric Clapton, just to name a few, as well as legendary drummers (Rod Morgenstein, Ringo Starr, Terry Bozzio), and bass players (Clarke, Andy West, Patrick O’Hearn). Along the way he earned a CLIO Award for recording “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” and two Grammy nominations, but has yet to win a Grammy.

Scott remains a vital force in the industry today, recording and producing, as well as releasing a virtual drum library, Epik Drums—A Ken Scott Collection, featuring five stellar drummers from his past, as well as Epik Drums EDU, a DVD set documenting his approach to recording and mixing drums. His latest effort is his just-released autobiography, Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust. Ken generously gave Premier Guitar an extended interview in the middle of a long day of book promotion, discussing how he approaches making music as a producer, and, of course, his approach to recording all those killer guitarists.

You actually started your career at Abbey

Road Studios at age 16?

That is absolutely correct, yeah.

How did you land that job?

Someone upstairs was looking after me! I

got fed up with school. One Friday evening

I wrote letters to about 10 places.

All those letters were mailed on Saturday;

I heard back from EMI [parent company

of Abbey Road] on Tuesday, had an interview

on Wednesday, and was accepted on

Friday. I left school that day and started at

Abbey Road the following Monday. Like

I say, someone upstairs was looking after

me. [Laughs.]

What was your first job there?

Tape library—just getting tapes, checking

in tapes, and making sure they were in the

right cutting room or studio.

How did you move from that into the

engineering side of things?

Via second [assistant] engineering, doing

that for a few years. My very first session

as a second engineer was on side two of

A Hard Day’s Night and I carried on with

them [The Beatles] all the way through

to Rubber Soul. Then I was promoted to

mastering—disc cutting. EMI felt it was

better to learn the final product before you

worked on the “easy” side of it. So you

could never become an engineer without

knowing the problems that may ensue if

you don’t give the cutter a good tape. After

doing that for a few years, I got the phone

call to move downstairs as an engineer.

After sitting next to one of the other engineers

for two weeks—just watching what

was going on—I got to push up the faders

on my very own first session, which happened

to be Magical Mystery Tour.

Working with The Beatles had to be

tremendously exciting.

Are you kidding? They were the biggest

band in the world at that moment in time.

Nothing bigger … it was terrifying! To put

it bluntly, I was shitting myself the entire

session. [Laughs.]

Obviously it worked out okay.

Well, they’d been to an outside studio and

recorded a version of “Your Mother Should

Know,” and Paul wanted to try a new

arrangement on it. So we were re-recording

“Your Mother Should Know.” The arrangement

didn’t work, so luckily anything I did

mess up, it didn’t matter anyway.

Working with them as a training engineer was incredible because you couldn’t really do too much wrong with The Beatles. You had the perfect set up for experimenting to find mics you liked. It wasn’t a typical three-hour session where you had an orchestra and you had to do two songs in a three-hour session—where you had the pressure, so you had to get it right from the get-go. With The Beatles, they were spending ages. They loved experimentation, so that gave you the freedom to try things. And also, if I wanted to try mic X on piano, which no one ever used, and I wanted to try it in a totally different place from anywhere other people mic the piano, and I pulled up the fader and it sounded like crap—nothing like a piano—The Beatles would turn around and say, “Wow, that doesn’t sound anything like a piano, we love it, keep it!” They didn’t want things to sound normal, so it was a perfect learning experience for me.

Why did you become a producer?

It was a combination of two things:

Engineering was becoming too easy. I’d

almost reached the point where I’d seen

some of the other engineers at Abbey Road,

where they could literally set up the board,

all of the EQ and everything on the mics

before the musicians even came in or they

pulled up faders. You get into habits of how

you record things, what works for you. I

was reaching that point.

There was that, plus something that a lot of engineers eventually go through … you’ll be sitting there next to the producer and suddenly you’ll have this idea. You tell the producer. He looks at you and pushes the talkback button and tells the artist, “You know what, we’re going to try this.” And the artist says, “Yeah, okay.” Then, if it works, the producer takes the credit. If it doesn’t work, “Oh well, that was only Ken’s idea anyway. I didn’t think it would work, but I thought I’d give him a chance.”

That was happening more and more. I wanted more artistic say.

Ken Scott cutting acetate in the studio. Photo courtesy of EMI Archives

What is the difference between an engineer

and a producer?

If you look at it from the film sense,

the recording engineer is the director of

photography and the record producer is

the director. [The producer is] there to pull

the performances out of the artists. They’re

there to help with the arrangements. The

producer can be a shrink, he can be a dictator,

he can be your BFF. He has to be a

million different things. But ultimately, the

way I look at my gig, it’s to get the best

performance out of the artist in the way the

artist wants it put across. There are a lot of

producers out there that go in, “It’s my way

or the highway” kind of thing, and they finish

up with it being more of the producer’s

record than it is the artist’s.

Do you go into a project with an end in

mind? Do you know what it will sound

like before you even start?

To a point. Not wholly. I don’t like to do

too much pre-production. I’ve found that

if you go in with a set idea of how something

has to be, something can change in

the studio. You do the song fractionally

faster or the sound is slightly different

from when you were in pre-production,

and a guitar part suddenly won’t work.

If you’re fixated on that guitar part or

whatever it is, you’re going to waste a

lot of time trying to get back exactly

what you had in pre-production—and it

might never work. So as long as the basic

arrangement is there going into the studio,

that’s it for me. I have a certain idea of

what it’s going to be like … it’s probably

50/50. I know 50 percent of what we’re

heading for, but leave the other 50 percent

up for grabs once we’re in the studio.

Ken Scott's Top Recording Tips

Here’s a short list of Scott’s own tried-and-true guidelines for making better recordings:

Legendary recording engineer and producer Ken Scott recently put pen to paper for the biography, Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust.

1. Make decisions as you record. Don’t wait until mixdown. According to Scott, “No one likes to make a decision, and it’s not just in music—it’s in life it seems. Everyone is second-guessing themselves. How many times have you been to the supermarket and you’ll walk past a guy with a cell phone to his ear: ‘Yes, honey, I know, but there are 10 different kinds of baked beans. Which kind is it I’m supposed to get?’ It’s just baked beans, come on. So you make a mistake, she’s not going to kill you for it. Make a bloody decision!”

2. Listen to many different musical genres and try to learn as much as possible from each. Don’t be afraid to experiment. It’s nice to have a total picture of where you are headed, but leave the final destination open to improv and creative discretion.

3. Your idea of sound should be constantly changing. “That’s how you grow,” Scott says. “A band like The Beatles, they were changing constantly. As they learned more and more, they would make things change. They would take the audience with them, and that’s how they managed to come up with such incredible stuff—they were always learning and they always wanted something to be different.”

4. Make recordings with the gear you have. Great recordings can be made with any level of equipment if the sources and performances are great.

5. Invest in good monitors and learn how they sound. Everything starts with being able to hear your tracks accurately.

6. Play out live as much as possible and learn from the audiences’ response to your performance. You’re bound to benefit from being exposed to other perspectives.

7. Pare down performances to the essentials. Focus on making the best song, don’t fixate on the individual parts to the point of losing the forest for the trees.

8. Go into recording sessions with an end in mind. Don’t worry about having every detail mapped out, but a good arrangement and a vision for the final result will make for a much more productive and successful session.

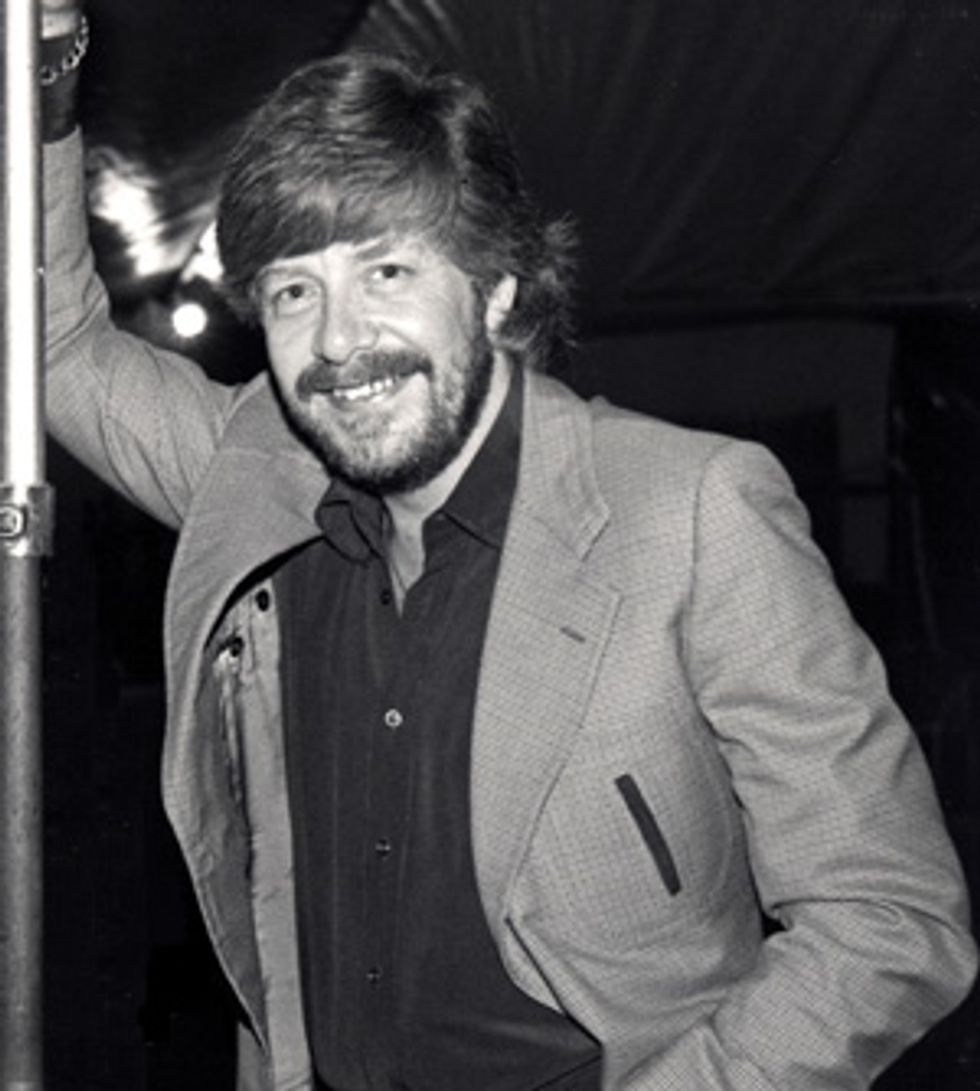

Ken Scott sports a managerial look, circa 1983. Photo courtesy of Ken Scott

Was that the same when you were

working with the Dixie Dregs? Steve

Morse composed all the parts in

advance, did he not?

Yeah, it was the same with the Dregs. The

first time I ever met them was in pre-production.

I walk in and they play their

first song, one called “Take It off the Top,”

and I stopped them in the middle and

immediately laid into the drummer [Rod

Morgenstein]. [Laughs.] He was just overplaying

so much, it was a constant battle

between him and everyone else. Steve was

trying to get as many notes in as possible,

the bass player was trying to get as many

notes in as possible, and Rod was trying

to get as many hits in as possible. We took

small sections of the song, and I just had

him pare it way down. He hated me. It’s a

great story between us, because he absolutely

detested me at that point because I was

stopping him from showing off. But once

he heard it starting to come together in the

studio, more as the song as opposed to their

individual pieces, then he suddenly realized

what I was getting at. He re-thought all of

his drum parts. He now says that thanks to

what I did that day, he still has a career.

I knew a little bit more about what had to happen—more than they did—right from that get-go. Once we’d laid down the basic tracks, then it was overdubbing. With Steve’s guitar, it was so sectionalized. One of the things that I loved working on with Supertramp was using as many different guitar sounds as we could get, and that’s what we did with Steve. It was, “Okay, we’ll take this verse … this part should be this kind of sound, this part should be this kind of sound.” We’d zero in on the sound, he’d play those parts, we’d double them or whatever, then we’d get the sound for the next part, and just patch it together like that. So, exactly what should the sounds be? I didn’t know up front. We had to find them.

It sounds like you need a well-developed

sense of psychology to work as a producer.

How do you read the musicians

and know how to handle them?

I have no idea! Take my history with Jeff

Beck. The first time I worked with Jeff,

it was to record the first Jeff Beck album,

Truth. It was a bunch of guys who weren’t

really known. Jeff had a bit of a reputation

from the Yardbirds, but certainly nowhere

near as big as Clapton was coming out of

that band. Little-known, generally regular

guys—they were a blast. They were really

fun to work with and they were really

good, obviously.

Then we complete the project. Album comes out, they tour the States, they come back to start on the next album. And the egos were through the roof! We couldn’t work together, it was obvious. I think we did one day and that was it—sessions got canceled because it just wasn’t working.

I don’t see Jeff for a while until I start to work with Stanley Clarke. Jeff comes in and plays on a couple of tracks on Stan’s albums, and he’s back to normal again—he’s a regular guy. It was really nice working with him again. No sign of that ego. Then I get to work with him again later on There and Back. It was the exact opposite of everything! He didn’t feel he was good enough to be playing with those musicians. On this occasion, I had to try and draw his performances out of him. I was sort of stroking his ego the whole time, “Jeff, you can do it, come on mate, this is easy for you.” That was very hard. I hadn’t had to deal with that before. That was a learning experience for me, trying to pull something out of an artist they didn’t think they were capable of. Generally, they go over the top. It’s easier to pare it down than it is to get it out of them.

You’ve done pop, glam, fusion, blues,

rock, new wave—all sorts of different

things. What drives you to work in new

musical styles?

I get bored. I used to drive my managers

crazy. Because they were getting a percentage,

they would like to book you up

as an engineer/producer for the next two,

three years, and know exactly what you’re

doing. I could never do that, I had to

wait until I finished a project and then

say, “Okay, bring me stuff.” Stuff would

come in, “No, no, I just did something

like that.” It was just trying to find

something I felt like doing. Although,

the weird thing is, I am a total creature

of habit. Recording drums, I can literally

set up the EQ before the kit is even in

there. With guitars, I always mic exactly

the same way. But musically, as a producer,

I need it to be different every time.

What is your approach to mic’ing an

electric guitar?

A Neumann U 87 about 18" away and

whatever you want for a distant mic.

How far away is the distant mic?

No specific distance.

Do you “tune” the placement by ear?

Yes.

Do you aim the close mic at the speaker

cone, the center of the speaker, or

another spot?

No. Actually, I just put it where it looks

right! [Laughs.]

Do you fine-tune it from there or just

set it and go?

Just set it and go, generally speaking.

Obviously, there are times that you try

different things. There was a track on the

Devo album, Duty Now for the Future,

where we wanted a very small, distorted

sound. We messed around trying to get

it, and we finished up taping some headphones

to a Neumann U 87. That gave

us a really small sound and it was exactly

what we were looking for.

So there are times that you modify it, of course. But generally, 90 percent of the time it would just be the U 87, set it in front, and that’s it.

Given your approach, it must be

essential to get the sound right at the

source—at the amp.

It’s always from the source, from the

performance to the sound. That’s one

of the things with the way we were back

in the day. Because we had so little EQ,

so few effects, the sound had to start in

the studio. I’m a firm proponent of the

performance has to come from the studio.

It really annoys me, all of the stories about

someone will do something and it’s, “Yeah,

that’s okay, we can just put it all together

in the computer.” No, get them to bloody

sing it right in the first place! Don’t use

Auto-Tune, don’t move everything around

so it’s on the grid. You’ve got to get the

performance. That’s the thing with Bowie’s

vocals. No, they’re not perfect. There are

places where they’re not quite in tune nor

in time. But they’re from his heart, they’re

from his soul. They’re performances. That’s

why, 40 years down the line, we’re still talking

about them.

Simple is Better

Left: Neumann U 87. Right: AKG C414.

Ken Scott calls himself a “creature of habit” when it comes to recording—he trusts specific techniques and gear. For electric guitar, he relies on a Neumann U 87 microphone, placed 18" in front of the speaker, plus a “distant” mic, placed farther away from the speaker. The type of microphone used for the distant mic isn’t critical, though the polar pattern will make a big difference. A cardioid mic will be more directional and pick up less room, a figure-8 mic will capture more room sound, and an omnidirectional mic will capture the most room.

Scott works to get the sound right at the source—at the amplifier—then captures it with his straight-ahead mic’ing techniques.

For acoustic guitar, a single condenser microphone—in Scott’s case, an AKG C414—is placed near the body, looking at the soundhole or bridge. The mic is adjusted by ear to find the ideal location.

If you don’t have access to these higher-end microphones (a basic Neumann U 87 costs approximately $3,200 and the AKG C414 is around $1,000), try using another largediaphragm cardioid condenser microphone. During his days recording The Beatles at Abbey Road, Scott often relied on an inexpensive AKG D19C condenser microphone for acoustic guitar, piano, drums, and many other sources. Today there are many large-diaphragm condensers on the market to choose from. Some affordable substitutes include the Behringer C-1 ($44), Samson C01 ($80), AKG Perception 120 ($99), Audio-Technica 2035 ($150), Studio Projects B3 ($160), Shure PG42 ($200), Rode NT1a ($230), and Mojave Audio MA-201 ($695).

Ken Scott recommends making recording decisions early in the studio, on the spot, rather than waiting until later. Photo courtesy of EMI Archives

How much do you feel that preamps

and other gear factor into the sound

that you get?

From my standpoint, very little. I’ve worked

in so many different studios and they’re

all different. For me, the most important

part of a studio—and the thing that has to

be right in the studio, there’s no two ways

about it—is the monitor system. Because if

the monitors aren’t right, then you have no

idea what you’re doing. You’re not listening

to the true sound. How do you work

with the sound if you don’t know that what

you’re listening to is right?

I put it that way—as being “right”— because we all like to hear things slightly differently. You get to know what you like to hear. You hear that inside the studio and outside the studio. Wherever you listen, you’re listening for a particular kind of sound.

How important is the actual recording

space that the amplifier or speaker is in?

It’s not. You work with what you’ve got.

As far as guitars go, I don’t think it makes

that much difference. There are times that

I’d love to have a guitarist in a big hall so

you can get all of that amazing reverb from

the distant mic. But generally speaking, it

doesn’t matter… [Pauses.]

I suddenly realized as I’m saying this, to a point I’m wrong! [Laughs.] There’s an example with Mahavishnu Orchestra where we started recording at Trident [Studios in England], and everything went great. This was Birds of Fire and we didn’t have enough time to do the entire album, so we came over to finish it off in the States. We were booked into Criteria, down in Florida. John [McLaughlin] immediately blew up two 100-watt Marshalls. What it was, the room was so dead. It was that time with the Bee Gees and disco, and the sound was very, very dead. John couldn’t get the sound out of his amp without blowing it up. Everything was turned full bore and it just sounded quiet. Everything was being sucked up. We finished up canceling the sessions and moving to [NYC studio] Electric Lady, which worked great. So that’s an example where, yeah, the room can affect everything.

What’s your recording process?

It depends on the musicians and the

music. With Missing Persons, because

Terry was one of the main writers, he

knew exactly what needed to happen

from the very beginning. Terry wanted

it to appear that the drums were pulling

everything along. He wanted to be ahead

of everyone the entire time. So the way

we worked with him was, it was just him

playing, no one else, no guide tracks or

anything. He just played the track. Once

we got a drum track that really swung,

that felt great, we knew we’d gotten the

basis for the track. Then we started to

overdub things. I felt so sorry for Patrick

O’Hearn, the bass player, because we’d

be doing a take and so often it was just

eighth-notes and Terry would be, “No,

no, no! You’ve got to hold back a bit. I’m

pushing, I’m pushing!” It was so minute

and Patrick was going through hell, but

it all worked in the end.

So in that instance, it was just drums. Other times, it’s bass and drums, just going for those. There are obviously times where I’ve gone for guitars, bass, and drums. And then I’ve overdubbed from there. It depends.

You’ve said that the best way to learn

to record is to limit yourself to 4-track

equipment.

Absolutely! It’s the thing of making decisions.

Because that’s something that, for

me, is missing these days. No one likes

to make a decision. That’s why albums

are taking three years now. They’ll record

something: “Tell you what, I don’t think

it will work, but let’s keep it until the

mix and make the decision then.” So

you finish up with 199 almost useless

tracks and you’re going to decide at the

end as to whether they work or not. It

makes mixing horrendous. Just make the

bloody decision up front. Have an idea

of the final product and make the decision

during the takes.

I always used to do it. We’d be going through, “No, that’s not the take,” and go back and erase it. I’d record over it and keep on doing it. The decision was made then and there: “Yes, that’s the take, we’ll keep it.” That’s why I would love engineers and producers to spend some time working on 4-track because obviously you have to make decisions.

Are you committing to compression

and EQ as it goes down?

Oh yeah, do it right. I like to hear the

record as we’re putting it together, the

final thing.

When it comes time to mix, you’re basically

able to push the faders up and then

just be creative with what you want to

do with the mix. You don’t have to worry

about making the tracks work.

Yes, absolutely. You already know it

works to 75-percent certainty, and it’s

just zeroing in on the other 25 percent

to make it magic.

Do you have a specific approach to

recording acoustic guitar?

My normal way of doing it would probably

be an AKG C414. I do it really

close, it’s angled at the hole or it’s angled

more toward the bridge end. I’ve found

that acoustic guitars are a little touchy.

You have to do more with the mic and

the mic placement with an acoustic guitar.

So I will experiment more with an

acoustic guitar, trying things.

Have you found any modern microphones

that are useful to you?

No—but there are always exceptions to

the rule. When I did Missing Persons,

the first set of recordings that I did with

them—which were originally supposed

to be demos, and they finished up being

amongst their most popular songs—we

went into Frank Zappa’s studio to record.

Frank had just had that studio built. He

was on the road and he wanted to come

straight back in and start working in the

studio. He knew my reputation for finding

every possible fault that there is in

a studio, so he allowed us to have it for

free knowing that I would find all the

faults and get them fixed before he came

back off the road. The problem was

that all of his best mics, which were the

ones that I would normally use, he had

on the road because he recorded every

single performance. So we had to work

with his sort of “B” mics. When you hear

the album, there’s a mix of some of those

tracks that we did there with the “B” mics

and the rest of the stuff I did at my regular

studio with the “A” mics and you can’t hear

the difference!

As I say, it’s down to the monitors,

because if you know what you’re listening

to, you can adjust to anything.

For someone who’s working at home

and they’re trying to do a professional sounding

recording, do you recommend

that they go rent some of those A-list

microphones or should they try to get the

sounds with microphones they can afford?

No, try and get the sounds with the microphones

they can afford. But make sure that

what they’re listening to is good.

So put the money in the monitors.

Yes, absolutely, every time.

How can an artist keep their creative

spark and be willing to take chances?

You have to make music for yourself, to

make you happy. You can’t make it to have

a hit. Too many acts these days, they’re

out there to get a record deal or to make

money or to become famous. The Beatles

never started that way, The Who never

started that way. Jeff Beck never started

that way. They started because they wanted

to make music. U2—the same. They

made music because they enjoyed making

music, and people started to like it. That’s

the way to do it.

If you’re doing it purely to make money, you’re never going to be happy. Because more often than not, you’re not going to make that money! If you’re making it to please yourself, at least you’ve always pleased yourself. If other people like it, that’s the icing on the cake.

The other thing is, play out live as much as possible. You learn your gig from the audience, from what they give back to you. You don’t learn your gig in the garage, rehearsing, rehearsing, and rehearsing. You don’t get to know what people think of what you’re trying to do.

Any other tips for capturing great guitar

recordings beyond what we’ve talked

about?

It needs to come from the guitarist in the

first place. If you take Mick Ronson, his

sounds were always unique. He’d get his

tone by going through a wah-wah, finding

the place where we all liked the sound and

then leaving the wah-wah there. You find

your own techniques to get what you want

across. It’s just a question of experimenting

and finding what works for you.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.