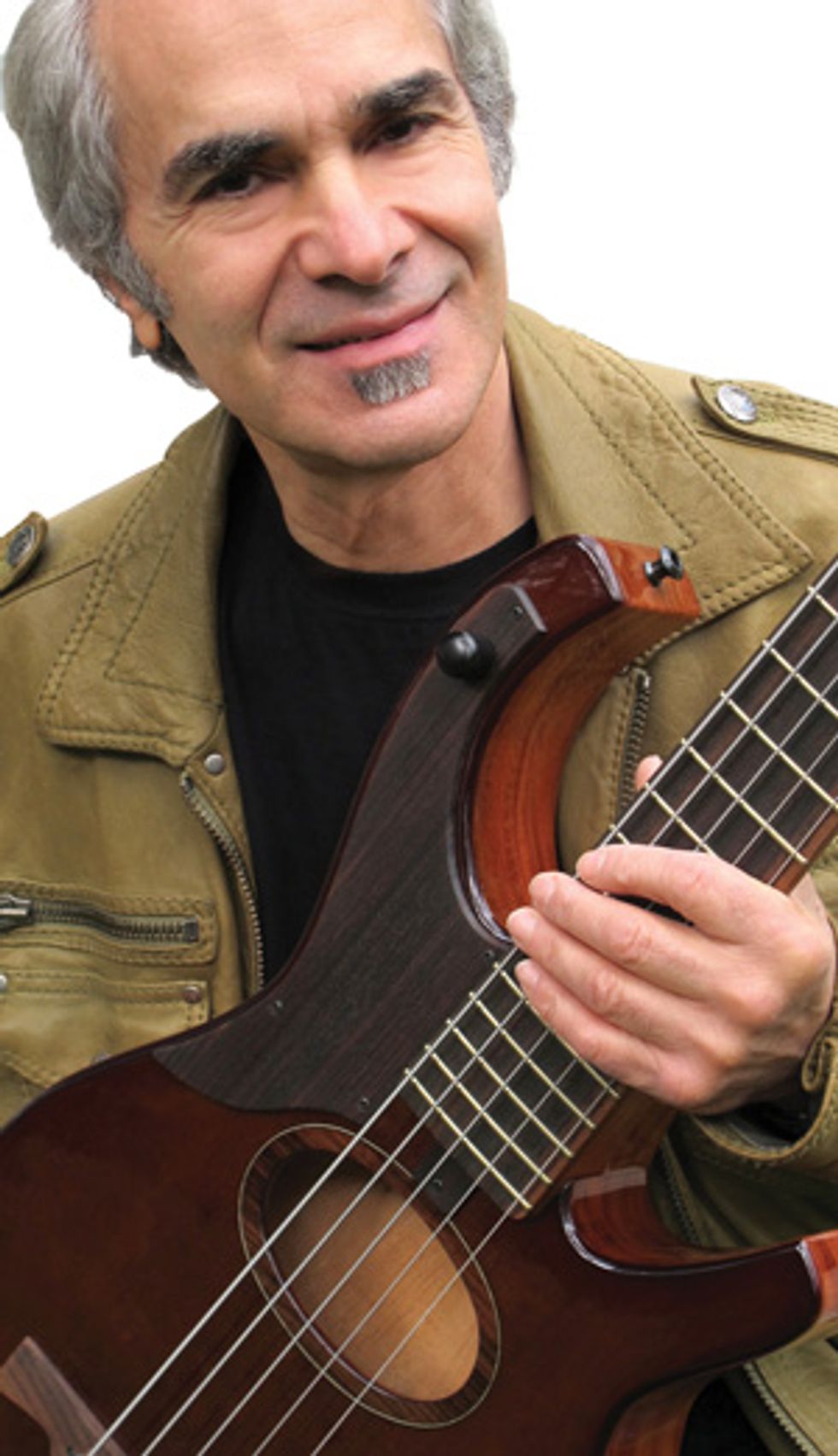

Working out of a oneman workshop in Woodstock, New York, Harvey Citron has been a respected member of the boutique luthier community for close to 40 years. Though best known for his hollowbody basses, Citron’s distinctively handcrafted instruments include solidbody basses, as well as a variety of guitars and baritones that have drawn the attention of artists across the genre spectrum, from Steve Swallow to John Sebastian to Doug Wimbish, among others.

With a background as both a guitarist and an architect, Citron is able to draw on his passion for both music and design when creating his absolutely unique offering of instruments. Aesthetically unique, yes. But he is also part of a very small group of guitar craftsmen with expertise in making their own pickups, and he winds, voices, and positions each one to complement the individual instrument. A true innovator, Citron’s distinctive, piezo-loaded and intonation-adjustable wooden bridge defines the combination of science and art.

Citron got his start as a luthier in 1974. Co-founding a partnership with Joe Veillette the following year, Veillette-Citron had an eight-year run during which a few hundred handcrafted guitars were produced. But eventually, Citron felt like a factory worker in his own business, putting in too many hours just to pay the bills. A desire to return to designing his instruments led him to set up shop as an independent luthier.

Premier Guitar recently caught up with Citron as he prepared to exhibit at the 2012 Montreal Guitar Show. Here he discusses his background and building philosophies, gives insights into modern lutherie trends, and even shares his thoughts on building a traditional acoustic guitar.

As a working musician and

former architect, which of the

two was the biggest inspiration

for your getting into

building guitars?

It’s actually very hard to separate

the two. I grew up being

interested in tools, working

with my hands, building things

since I was very little, playing

guitar by age 11, and loving

music completely. I attended

Brooklyn Technical High

School where I studied drafting

and engineering, and then studied

architectural design at City

College School of Architecture.

I was incredibly frustrated as I

started out working as an architect,

since I was not really doing

anything more than producing

working drawings of others’

designs. I was very young, but

had a fire burning inside to

create. I was creating through

my music—and my furniture

and interior design—but not

through my job. Then the

opportunity came to build a

guitar. Because of all my years

drafting and studying design, I

knew I could look at a guitar,

understand how it was built,

and could actually build it! I

could explore to my heart’s content.

So what better avenue for

a musician and a designer? I was

able to meld these two areas of

creativity that I loved.

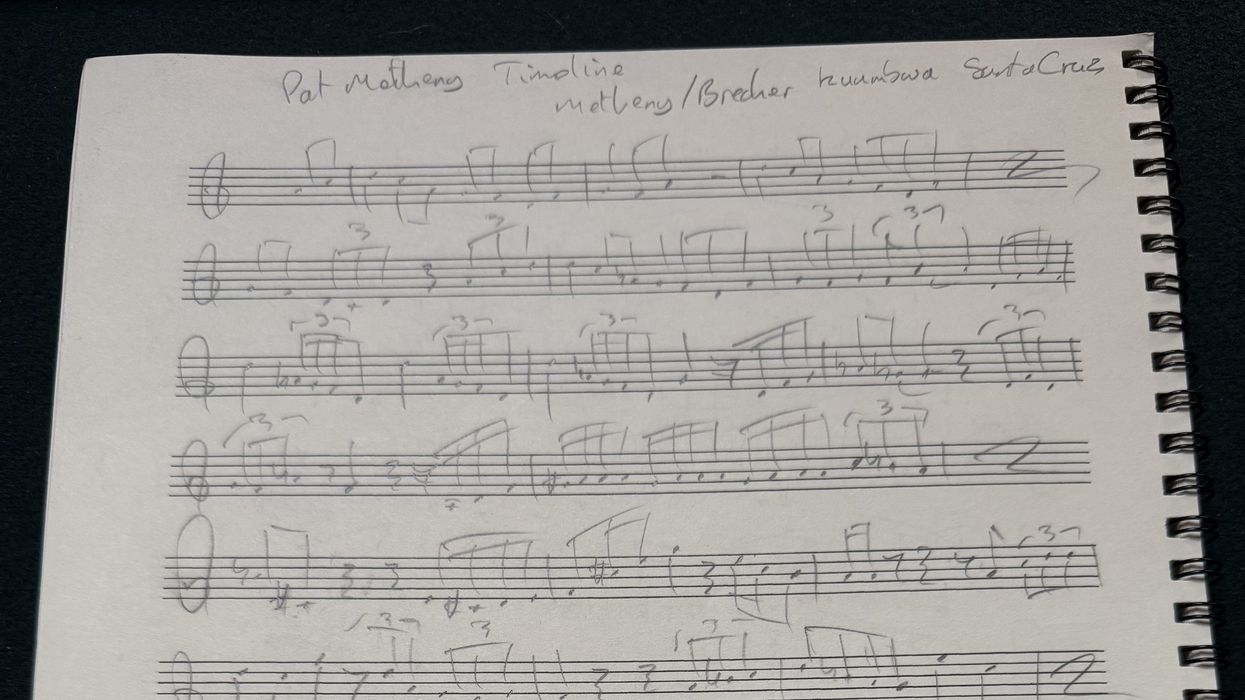

Built for renowned jazz bassist Steve Swallow, Harvey

Citron’s AE5 Swallow bass is an acoustic/electric

5-string with a 36" scale length using Honduras

mahogany for the body and neck, spruce for the top,

and rosewood for the fretboard and bridge.

Which has had the biggest

influence on your work?

Again, it’s very hard to say

which has been the larger influence.

As a designer, I have

always been seeking out what

hasn’t been done yet, or to solve

a problem. Each of my instrument

models sets about creating

something new sonically and/

or physically—they are not just

pretty boutique instruments.

Because I am a designer, I can

play with woods, construction,

electronics, and shapes. Because

I am a musician, I can use those

elements to explore new tone.

What were your formative

influences insofar as guitarists,

bands, and instruments?

I started playing guitar in the

1950s at a very early age and

was listening to people like Elvis

Presley and Chuck Berry. But

I only had an acoustic guitar

at the time. We were poor and

my mom bought the cheapest

Martin you could buy—a

00-17 with a mahogany top and

no binding. I did everything

with that guitar and amplified

it with a DeArmond pickup

and an Ampeg Rocket amplifier.

Even later on, I was using

that same guitar for soul music.

Developing my own style back

then, I was pretty much a

rhythm guitar player for a long

time, but later on became a lead

player, too.

Eventually you began building

basses as well. Was your

attraction to the rhythm side

of playing part of the reason

for that?

I just love instruments and

playing. Building basses for

me was always part of the deal

from the beginning somehow.

Veillette-Citron’s first prototypes

were a 6-string neckthrough

electric guitar and

4-string neck-through electric

bass. Our first batch of instruments

was also mixed, and

I’m sure we built more basses

than guitars over the years our

company existed from 1975 to

1983. With the exception of

Alembic, bass design had not

really been explored that extensively

in the mid-’70s. While in

process of building our first two

prototypes in 1974, I visited

the Alembic woodworking shop

in Cotati, California. It was a

mind blower. I was enamored of

their work, and followed their

lead somewhat in construction

at Veillette-Citron. I have

always noticed that bassists are a

little more open to new sounds,

and are already hi-fidelity minded.

So many guitarists are looking

for the sound that a hero

of theirs made some time ago,

and they are under the illusion

that it if they have the same

equipment, they can recreate

that tone. I never had the desire

to build what has been made

before. It also seemed like there

were more orders for basses.

Citron’s intonation-adjustable rosewood bridge on the AE4 Swallow features bone saddles and six EMG under-saddle piezos.

Why is that?

It’s always been my impression

that there are far fewer bassists

than guitarists. Therefore, the

chances of a bassist working

are much higher than that of a

guitarist. And the quality of the

bassist doesn’t even have to be

as good necessarily, because you

need them and there aren’t that

many around. [Laughs.]

Can you tell us about your

pickups and how you got

started making them? Was

it a matter of wanting to be

involved in all components

of building? Was it out of

necessity or just an interest in

electronics?

Pickup making and guitar

making came about

simultaneously for me. I

knew some pretty serious

players in the guitar electronics

field way back, found out how

to wire a guitar, and then how

to build pickups. It was very

exciting to build a pickup. The

person who taught me how to

build them was Sal Palazolla,

who worked with Bill Lawrence

making pickups downstairs in

Danny Armstrong’s shop on

LaGuardia Place in New York

City. This was in 1974. The

first guitar I built had some

pretty strange pickups, and

people started asking me to

modify their guitars with my

pickups and different switching

arrangements. Veillette-Citron

started building prototypes in

late 1975 and those instruments

included my humbucking

pickups. We liked the idea of

having a part in virtually every

piece of the instrument, from

making our own pickups to

the bridge hardware and strap

pins. Though when I started

Citron Guitars and Basses in

1994, I had no desire to build

my own pickups, except for one

very unique single-coil that I

began to make for some models.

As time went on, I felt that

my pickups would make my

instruments more unique, so I

currently build several kinds of

single-coil guitar pickups, guitar

humbuckers, bass humbuckers,

and J-bass-style

pickups. They are

extremely popular and are,

in fact, used in other luthier’s

instruments.

What makes your pickups

unique?

One of the unique aspects of

my pickups is the multiple

gauges of wire in each pickup

using my own recipe. Each

gauge of wire has its own intrinsic

tone and I call my pickups

“custom blended.” I also voice

each pickup for its placement.

Pickups closer to the neck

require less resistance as there

is so much string excursion.

Pickups closer to the bridge

require more resistance since

there is so much less string

movement in that position.

What do you consider to be one

of the coolest or most important

advances you’ve made with

Citron Guitars and Basses?

The greatest and coolest thing

I’ve done has been the development

of my hollow instruments.

They are unique in

construction, electronics, and

most importantly, in their tone.

They are huge sounding, spatial,

deep, and possess incredible

sustain.

Like the AE5, the

body of the AE4

Swallow bass is

hogged out from 3"

thick Honduras mahogany

and utilizes

x-bracing for its

spruce top.

Can you walk us through the

evolution of your hollowbody

instruments? What was your “I

gotta do this” moment, and how

long did it take to get there?

My inspiration actually had a

lot to do with the Unplugged

show on MTV and having a

number of different instruments

in my hands. I had this idea

that I was going to have a hollow

bass, and initially, I thought

I was going to bend the sides

on it and have to make it headless

so it wouldn’t be neck

heavy. As it turned out, I ended

up deciding to hog out a piece

of mahogany for the bodies

instead, but the first three

or four were headless. I then

came up with an intonation adjustable

wooden bridge using

saddles with brass shims. With

it, you could move the saddles

but it would still actually react

sonically like a wooden bridge

with bone saddle. But this

didn’t allow me to use any traditional

piezo elements, so I was

using an undertop transducer.

It sounded okay, but it fedback

a lot. Additionally, by building

the headless instruments, I

realized I was limited with the

hardware, string spacings, and

nut width. The body was actually

heavy enough that I didn’t

need it to be headless, so I

moved to putting the head back

on the instrument.

So here I am, going back to a traditional piezo. I called up an old friend who’s a wellknown specialist in the field and told him I wanted to build an intonation-adjustable wooden bridge with piezos in it. He told me: “It can’t be done and no one cares.” [Laughs.] He knows a lot about this stuff but I wasn’t willing to just put a single 1/8" bone saddle in the bridge. I made the saddle 5/16" and made the whole bridge able to move with the piezo in it. That was the least I could do as far as I was concerned, and I left it at that for a while.

Since this model’s inception, I had been thinking this bass was going to be great for Steve Swallow. Steve tried the one with the 5/16" bone saddle, loved the sound of it, said he had to have it, and that he’s always wanted a wooden bridge with piezo. But he also said that an intonation-adjustable bridge would be a great plus if I could do it, because he’s such a nut about intonation. For some reason or other, that was all the impetus I needed to get this new bridge together. And it was then I realized how close I was to making it work. The idea came to me that if I considered my 5/16" saddle a sub-saddle, I could put moving parts (bone saddles) on top of it with piezo underneath. This led to my first intonation-adjustable bridge and it had a single piezo under the leading edge of what I call the sub-saddle (made from ebony). I put slots in it and made bone saddles with little pins in them so the saddle could slide.

There have been improvements since then—the subsaddle is now 3/4" deep and the saddle pins have been replaced with brass tabs. Also, the underside of the sub-saddle is segmented so each string acts as if it has its own individual support. This provides less likelihood of problems with warpage of the sub-saddle, which would cause uneven string pressure.

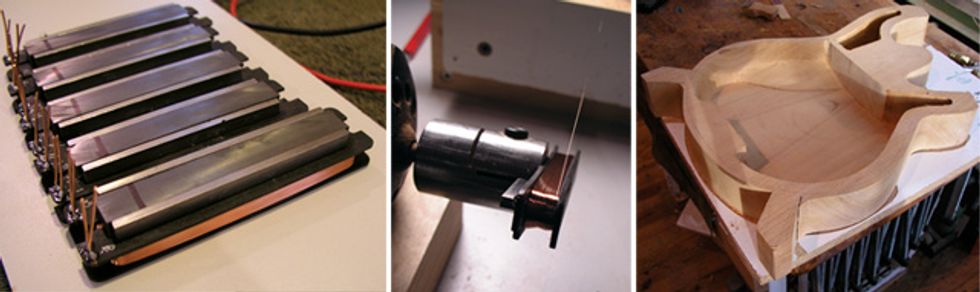

LEFT: 5-string bass pickups- the coils have been wound, and the pickups put together with their magnets, just before being placed in fully shielded covers

and potted in epoxy. CENTER: Pickup coil being wound. Photo by Janet Perr RIGHT: The interior of an AE5 Swallow bass.

Is there a particular current or

recent trend in lutherie that

you see going away in 15-20

years and is there one particular

current or recent trend in

lutherie that you see having a

major effect on guitar makers

in 15-20 years?

The unsustainability of many

of the beautiful hardwoods is

an ongoing problem in the

guitar business. I use Honduras

mahogany for my hollow instruments,

and also for the necks of

other models. Honduras mahogany

is the material that has been

used primarily and traditionally

for acoustic guitar bodies and

necks. It’s very stable, machines

easily, and has a wonderful tone

that’s sweet, warm, crisp, and

delicious. It has become harder

and harder to obtain, and the

quality I see has been going

down. The trees that are being

harvested are much younger,

and who knows how long the

supply will last. I think guitar

makers are going to have to start

using other woods. I have been

resisting the change, but I expect

it is inevitable.

In your 40 years of building,

what is one of the most

important advances you’ve

seen in lutherie or guitar

manufacturing?

I think one of the most

important advances in guitar

manufacturing is the widespread

use of CNC machines. These

machines make reproduction

very accurate and time efficient.

Also, polyester finishes are great

because they are extremely durable,

as opposed to nitrocellulose

lacquer and acrylic urethanes.

Do you utilize CNC?

No.

A number of boutique luthiers

are hesitant about using CNC,

feeling that it may take away

from the handcrafted aspect of

a build. Is that your reasoning

as well?

I’m open to having someone else

do particular things for me on

CNC and I don’t see any shortcoming

in that. The problem for

me is that I’m a small builder.

For instance, I’m building a

batch of five basses right now—

two of them are 34" scale, one

is a 35" scale, one is a 36" scale,

and the other is a prototype

for Steve Swallow. They’re all

different, both internally and

externally. How would I pay

for the tooling when the whole

mechanism of CNC is geared

towards production? That’s the

only thing that’s held me back as

far as that’s concerned.

LEFT: A top being glued on to an AE series bass. RIGHT: Harvey sanding one-piece Honduran mahogany AE5 Swallow necks. Photo by Janet Perr

There is one part of my hollowbody that is incredibly painstaking and there’s no advantage to how I do it. It’s just the only way I can, shy of using CNC. Imagine a hollowbody instrument that’s been hogged out a 3" piece of mahogany that has a waist cut. Trying to make that material on the inside parallel is a handcarving job for me. It’s time consuming, it’s not fun, and it’s not necessarily better. It’s just the way I have to do it [laughs]. That’s okay, I can do it, but CNC would be great for something like this.

What’s the ratio of guitars

to basses that you build? Is

it market driven or do you

build what’s inspiring you at

the time?

Except for a prototype that I’m

currently building for Steve

Swallow, everything is order driven.

As far as the ratio, it’s almost

all basses right now. What I’m

most known for are my hollow

basses and they require a lot of

time to build. Steve Swallow is out

there playing them, and while his

audience may be small, they are

loyal. People have been wanting

those instruments—either what he

plays, or what he plays modified

to be a hybrid between his bass

and my regular A-series basses.

How many instruments do

you produce in a year and

how can people find out more

about them?

My website has beautiful,

detailed photos of all of my

models, as well as a price list,

photos of the shop, upcoming

events, and videos. Many of the

guitars and basses I build are

customized to the preferences

of each musician. I will often

change the string spacing at the

bridge, the neck dimensions, and

tweak the electronics, among

other things to suit my customer’s

needs. I generally build

between 12 and 20 instruments

per year with the Swallow bass

being my most popular model.

An AE5 Swallow bass after it has been shaped on the pin router. “This one features Steve Swallow’s very narrow neck—it might be the last body I made for Steve,” says Citron. Photo by Janet Perr

Given your expertise with hollowbody

instruments, have you

ever had the desire to build a

traditional acoustic guitar?

Yes, yes I do [laughs]. I’ve been

thinking about it for a long time.

But as you get older, I think life

gets busier somehow and the

opportunities for messing around

get harder to squeeze in. What I

need to do is learn more before I

do it. Unlike many other builders,

all this stuff has never really

been about the craft of building

for me. The craft is my vehicle to

hear what I imagine. For some

reason, I don’t really have the

desire to build a Martin guitar.

That said, my favorites are the

Martin D-35s from the ’60s, the

dreadnought Guilds of that period,

and the huge Gibsons. But I

feel that before I build an acoustic

guitar, I want to really understand

what made those guitars sound

the way they do.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig