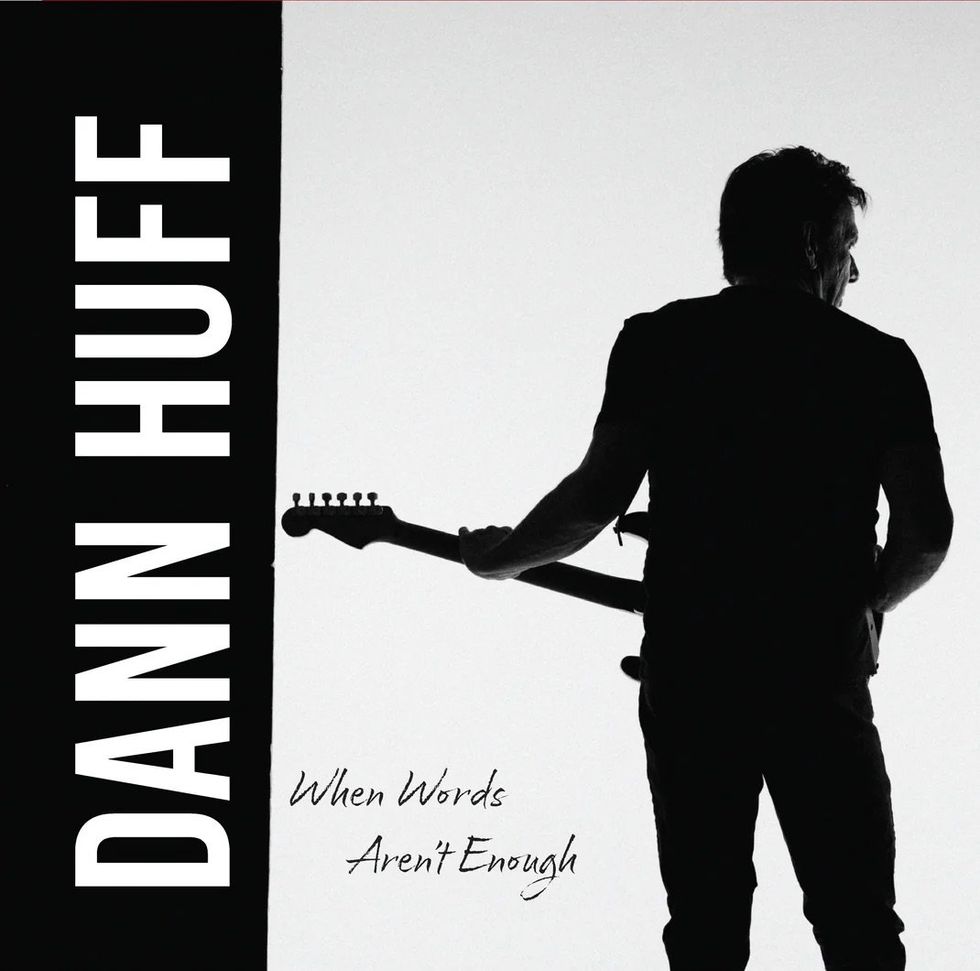

You wouldn’t expect Dann Huff, one of the most renowned studio guitarists, to feel nervous sharing his debut solo LP with a friend. But when that friend happens to be Toto’s Steve Lukather, a permanent fixture on the Mount Rushmore of L.A. session players, it’s easy to understand the butterflies.

“He said, ‘I want to hear your record,’” recalls Huff, 64, with a laugh, detailing the creation of the colorful and lovingly arranged When Words Aren’t Enough. “I said, ‘Sure, I’ll send it to you.’ Then as soon as I pressed send, I went into this almost-fetal position mentally. I thought, ‘I just sent it to one of the people I value so highly in my life.’ But it was great, the fact that I felt the fear.”

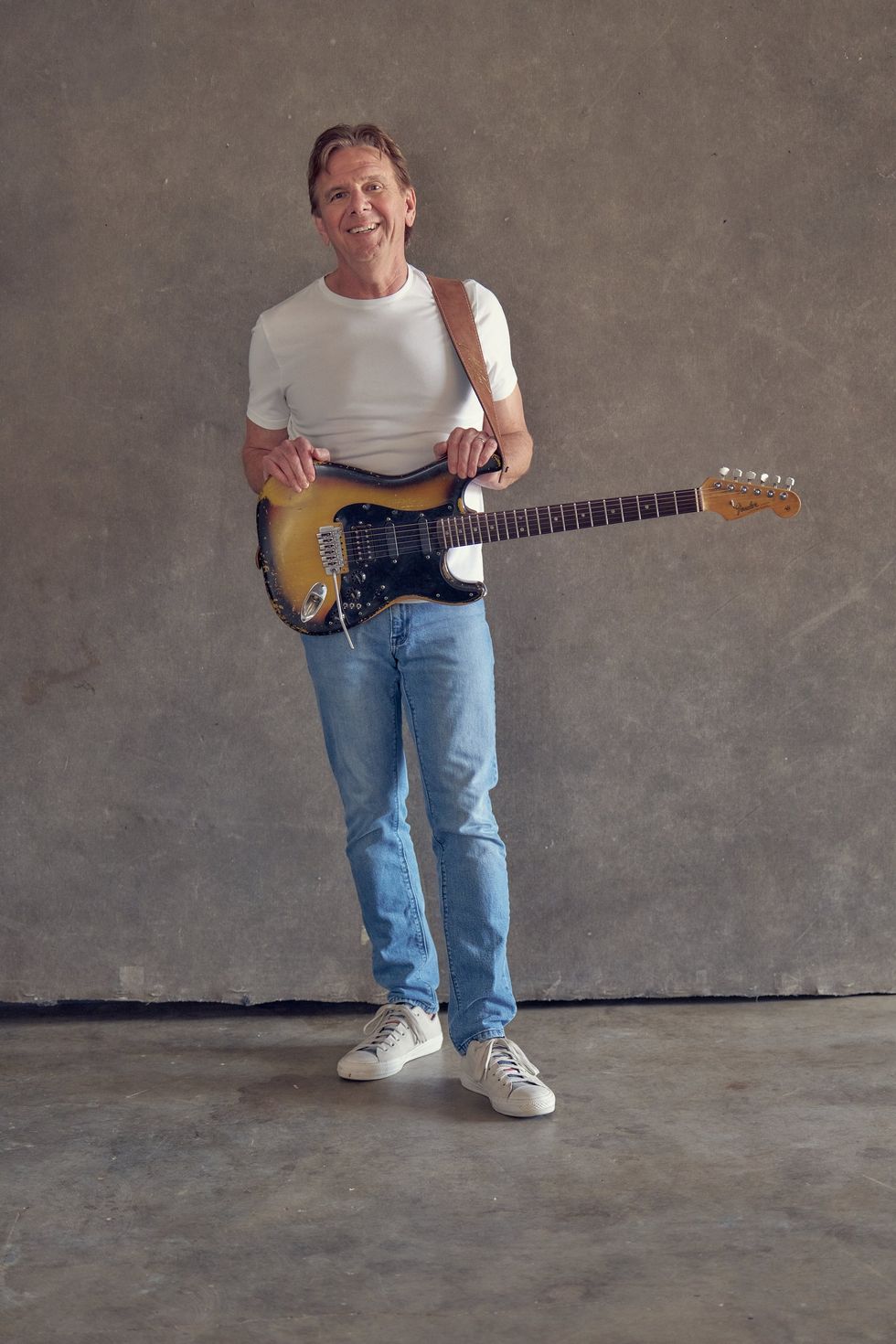

That story crystalizes the skills that propelled Huff to this moment: the confidence and curiosity it took to press that button, but also the humility it took to still feel those healthy nerves. After all, you have to be great—but also a flexible team player—to rack up the credits this guy has. And he’s had a career like few others in the business, both in the styles he’s explored and the roles he’s served: Huff rose up the ranks of the fertile ’80s session scene, where he recorded with everyone from Michael Jackson to Kenny Rogers, has played in both a contemporary Christian rock band (White Heart) and an AOR outfit (Giant), journeyed back to his hometown of Nashville and immersed himself in the pop-country world (Shania Twain, Faith Hill), ventured into marquee-level production work (most famously on Taylor Swift’s 2012 blockbuster, Red), and now—finally—released a fascinating album of his own.

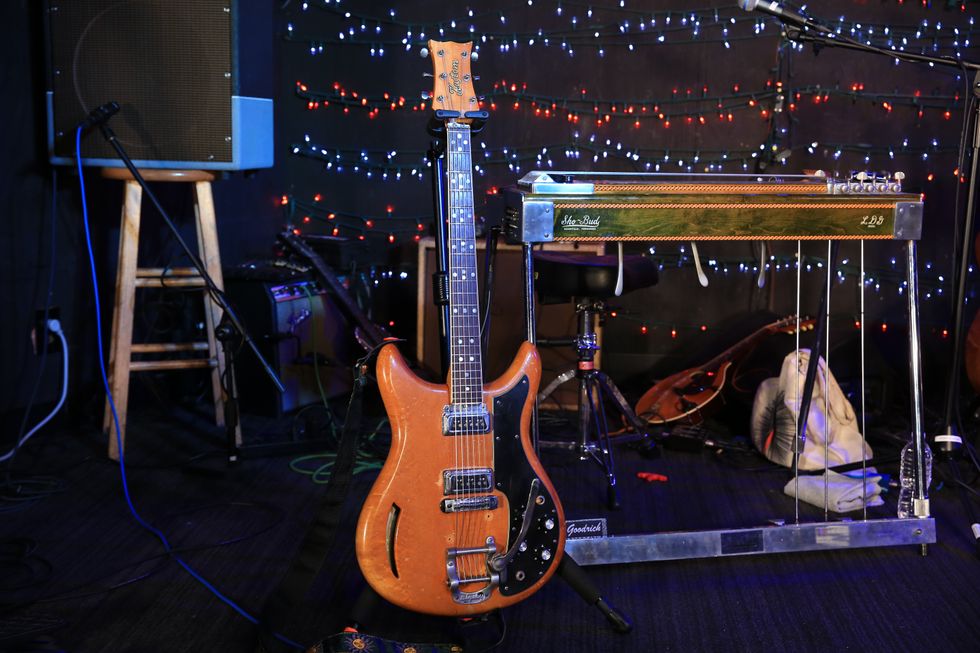

Dann Huff’s Gear

Guitars

James Tyler Dann Huff Classic

1964 Fender Stratocaster

1959 Fender Custom Shop Stratocaster Reissue

Yamaha Classical Guitar (gut string)

Amps & Cabinets

REVV Dynamis D40 (40-Watt Tube Amp Head)

Matchless amps

Little Walter 2x12 Open Back Cabinet

Effects

Boss OS-2

Mr. Black SuperMoon

JAM Pedals Wahcko

“As soon as I pressed send, I went into this almost-fetal position mentally. I thought, ‘I just sent it to one of the people I value so highly in my life.’ But it was great, the fact that I felt the fear.”

When Words Aren’t Enough nods to so much of that range, moving from simmering dixie funk to cinematic orchestral rock to atmospheric and artful Americana. It sounds like the work of an artist stretching every single muscle yet never straining in the flex—a series of clean and jerks that sound awfully clean. But you can’t talk about this ambitious endeavor without exploring its true roots. “This project for me is basically a love letter to my emerging years, which is the late ’70s,” Huff says. “It’s everything that I built upon, everything that I love in guitar playing.”

The groundwork was laid when Huff was a kid. When he was around 10, his parents moved from the Chicago area to Nashville—with three sons and a whopping $800 to their name—as Dann’s dad, Ronn, pursued a career in orchestration. (“Man, he had some big cojones to do that!” Dann says, accurately.) The elder Huff’s career took off, and he found work with the Nashville Symphony, as well as occasionally in recording studios with rhythm sections. The latter intrigued his son, whose interest in the guitar started to grow around age 12. Dann had felt a sense of culture shock in Tennessee, but music became his guiding light. The more he glimpsed of his father’s work life, the clearer his path became. “My dad had a friend who was a session guitar player in Nashville named John Darnell, and he asked if [John] would come over and spend maybe 30 minutes to an hour with his 13-year-old son,” he recalls. “He came over one night, and I’ll never forget it. He taught me some scales and a couple chords. He kind of lit the fuse, and that was it.”

As an aspiring guitarist, the young Huff had the perfect entry point. His dad would offer to let him sit in the back of the room at the studio, where he’d meet “the cream of the crop” session players in Nashville—guitarists like Reggie Young, Pete Wade, and Dale Sellers. “To me, those were the rock stars,” he says. “You could go into a dark-lit studio, hear music for the first time, and make something new. I just thought that was the coolest thing. Why? I have no idea. There was no illusion that I wanted to go and be a rock star. Not even in the slightest, when I was a kid.”

When Words Aren’t Enough is rooted in the music of the ’70s—Huff’s formative listening and learning years.

“This project is a love letter to my emerging years, which is the late ’70s. It’s everything that I built upon, everything that I love in guitar playing.”

As a high-schooler in the mid ’70s, after years of practicing his chops in the basement, that dream started to become real. He played on friends’ demos at the local Belmont University, and he soaked in torrents of incredible instrumental music of that era: Larry Carlton, Lee Ritenour, Jeff Beck’s Blow by Blow, and Al Di Meola’s Elegant Gypsy, as well as Steely Dan’s Aja. “The list could go on, but it was so diverse," he says. “I was inundated with all these different kinds of music, all the Motown stuff. Everything interested me. And all of the sudden I started seeing these West Coast session players.” After playing on an album by singer-songwriter Greg Guidry, he was directly connected to some of those musicians, including former Toto bassist David Hungate. He was eventually hired for an L.A. session with soul legend Lou Rawls, kicking off a period of frequent commuting.

“At the time, Steve Lukather had all but vacated his chokehold—he was simply just the very best—because he was becoming a rock star,” Huff says. “I started booking myself on sessions. Back in the early ’80s, they still used contractors for a lot of the pop sessions. I said, ‘Just book me like I live out here.’” He would go out for stretches at a time, making a name for himself in L.A., but realized that this process wasn’t sustainable: “I didn’t realize I could charge for my hotels, my rental cars,” he says. “I did my own cartage. If I booked a session, my expenses would usually surmount that by 100 percent. But I was smart enough to realize I was investing in something, and it became apparent over the course of a year that I couldn’t keep hopping on planes, playing on big records in L.A., and coming back to play on demos in Nashville.” Around age 21, he and his new wife hopped on a plane and headed west, starting the next chapter of his life.

The ’80s flew by in a stream of sessions: Michael Jackson’s Bad, Barbra Streisand’s Emotion, Chaka Khan’s I Feel for You, Bob Seger’s Like a Rock, Whitney Houston’s self-titled, Madonna’s True Blue—every situation was different, and the ever-curious Huff learned something from almost all of them. “It was one of those perfect storms,” he says of this prolific time. But after the unexpected success of Giant, his melodic rock band featuring his brother David on drums, following the release of their 1989 debut, Last of the Runaways, he decided to move his talents back to Nashville. “I felt I didn’t need to do my studio career anymore,” he recalls. “[My wife] and I had just had our first kid, a daughter, and we felt, ‘As long as I’m gonna be doing this rock thing,’ which I’d never dreamt of doing, ‘we might as well do it from the comfort of where the rest of our families are,’ so we moved back to Nashville and I left my studio career. We cut a second Giant record, and by that point, Nirvana and Pearl Jam were out, so say no more.” Rather than move back to Los Angeles, he quickly found a niche in the Nashville scene, particularly within the world of country-pop/rock, playing on a series of enormous records—including a pair of multi-platinum monsters by Shania Twain, 1995’s The Woman in Me and 1997’s Come on Over, both produced by the singer’s revered then-husband, Robert “Mutt” Lange.

Toto guitarist Steve Lukather was one of the first to hear Huff’s new collection. After Huff sent it, he was petrified—but the fear was invigorating.

Photo by Nathan Chapman

“I don’t have any illusions of what I can do on the guitar, so I have to dig deep into what I actually have roots in.”

Huff was once again ingrained in the session world—just a very different one—but Lange noticed his potential in another field. "I didn’t get into producing records because I wanted to," Huff admits. "I was lured into it, or encouraged into it, mainly by Mutt Lange. He sensed that the way I played studio guitar, I knew that it wasn’t about me. It’s about building something.” And that sense of songcraft, of having an eagle eye for arrangement and talent, served him well when he made that jump, working with artists like Swift, Rascal Flatts, and even Megadeth. It also wound up informing his first solo LP, When Words Aren’t Enough, which came about after some friendly prodding from fellow Nashville musicians Tom Bukovac and Mike Reid.

“Both challenged and embarrassed me: ‘Why don’t you play guitar anymore?’ ‘I play guitar on the records.’ ‘No, why don’t you play guitar?’” he says. “I didn’t have a good answer after saying no for dozens of years. I decided I would give it a rip. I wasn’t in tip-top form of guitar playing at this time, so it was humbling, but it felt right.” He gradually started putting together some demos, drawing on the pivotal period of teenage inspiration that first drew him to this wild life. “Runaway Gypsy” laces jazz-funk riffs with grooving Latin percussion and grand string parts—a cinematic stew that reflects the influence of Al Di Meola. The title of “Southern Synchronicity” is an overt nod to Police guitarist Andy Summers, but the song is way wilder than you’d expect, with shifting time signatures, funky drumming, and the fiery fiddle of Stuart Duncan. Meanwhile, the greasy “Colorado Creepin’” is a tightly coiled, wah-heavy highlight. (“You can probably hear a lot of my love of Jeff Beck,” notes Huff.) Every track—featuring the core of Huff, bassist Mark Hill, and drummer Jerry Roe—is virtuosic but tasteful, placing every show-stopping solo within the context of a hooky melody and satisfying musical arc.

Fellow sessions aces Tom Bukovac and Mike Reid prodded Huff into recording and releasing his own original music.

Photo by Nathan Chapman

Often utilizing large chunks of his demos, they knocked out the bulk of basic recording in a couple days—and that no-nonsense approach fits for a guy who spent decades as a quick-on-his-feet hired gun. The process made Huff “fall in love again” with his Stratocaster, which he hadn’t played for years, but the recording was intentionally bare-bones. “It wasn’t about amplifiers or all the equipment,” he says. “I used very little equipment on the record. When you’re trying to say something, just say it how you’re gonna say it.

“The gift of being older and not being, shall we say, in my ‘prime form’—my chops aren’t as fluid as they were when I was playing 10 hours a day—is that I had to define what I was interested in before I did this,” he says. “And what I’ve always been drawn to in music—and I saw a connection here—is composition. When the shape, the form, the melody, the dynamics, are correct, that allows you to improvise over it in a way that isn’t gratuitous or about you trying to prove yourself. I don’t have any illusions of what I can do on the guitar, so I have to dig deep into what I actually have roots in.”

He also wound up enormously proud of the record—but that’s not to say he didn’t feel anxious about it, illustrated by his exchange with the great Lukather.

“I went through a period after I finished this thing where I was absolutely terrified,” he admits. “I guess anybody would. It’s hard to hear yourself from another perspective. I can listen to other guitar players or musicians, and I just want to hear who they are. I’m critical, but with my music, it’s like, I know where the warts are, and I hear the limitations. It’s hard to hear it for what it is, but I thought, ‘If I don’t let go of this thing and stop trying to impress myself or everybody else, I’m never gonna do this.’ So I said, ‘Fuck it. I’m gonna put it out.’ So I let go, and that was the best decision I could have made.”

YouTube It

In this two-and-a-half-hour video courtesy of Vertex Effects, Dann Huff does a deep dive on his most recognizable guitar parts over the decades.

![Fontaines D.C. Rig Rundown [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/image.jpg?id=60290466&width=1245&height=700&quality=85&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Mustang Muscle

Mustang Muscle

![Rig Rundown: Umphrey’s McGee [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=60219771&width=1245&height=700&quality=85&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)