In Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed, the German filmmaker, opera director, actor, and author tells his colleague Paul Cronin, “Walk on foot, learn languages and a craft or trade that has nothing to do with cinema. Filmmaking—like great literature—must have experience of life as its foundation.” When applied to the story of Lloyd Baggs, founder and owner of the L.R. Baggs Corporation, who’s been a cellist, car mechanic, aspiring racecar driver, fine-art printmaker, photographer, and self-taught guitar builder and acoustic pickup engineer, Herzog’s sentiment grows legs.

“I had intended at some point to retire and head off into the sunset as a photographer,” Baggs tells me over a Zoom call, concluding that he’s become content with the other paths down which life has taken him. “Being out doing landscape photography helps me think and organize my thoughts for the business, and I get lots of inspiration while I’m out letting my imagination soar, thinking about anything but guitars. If you cut me, I’ll probably be bleeding ‘photographer’ before anything else.”

That approach has yielded not only a successful business, but one of the best in its league. And, on November 1, L.R. Baggs debuted the AEG-1—the acoustic pickup manufacturer’s first ever guitar—a high-quality acoustic-electric whose body is made of plywood. Ask anyone you know in the industry, and they’ll tell you it sounds amazing—and not just for a guitar that’s made of plywood.

Not only is its sound impressive, but, appearing alone on the roster in the year of its company’s 50th anniversary, it seems to have come out of nowhere. We know L.R. Baggs’ status within the acoustic pickup industry, yet suddenly, they’re spelling out a new name for themselves for acoustic-electric guitars. Why now?

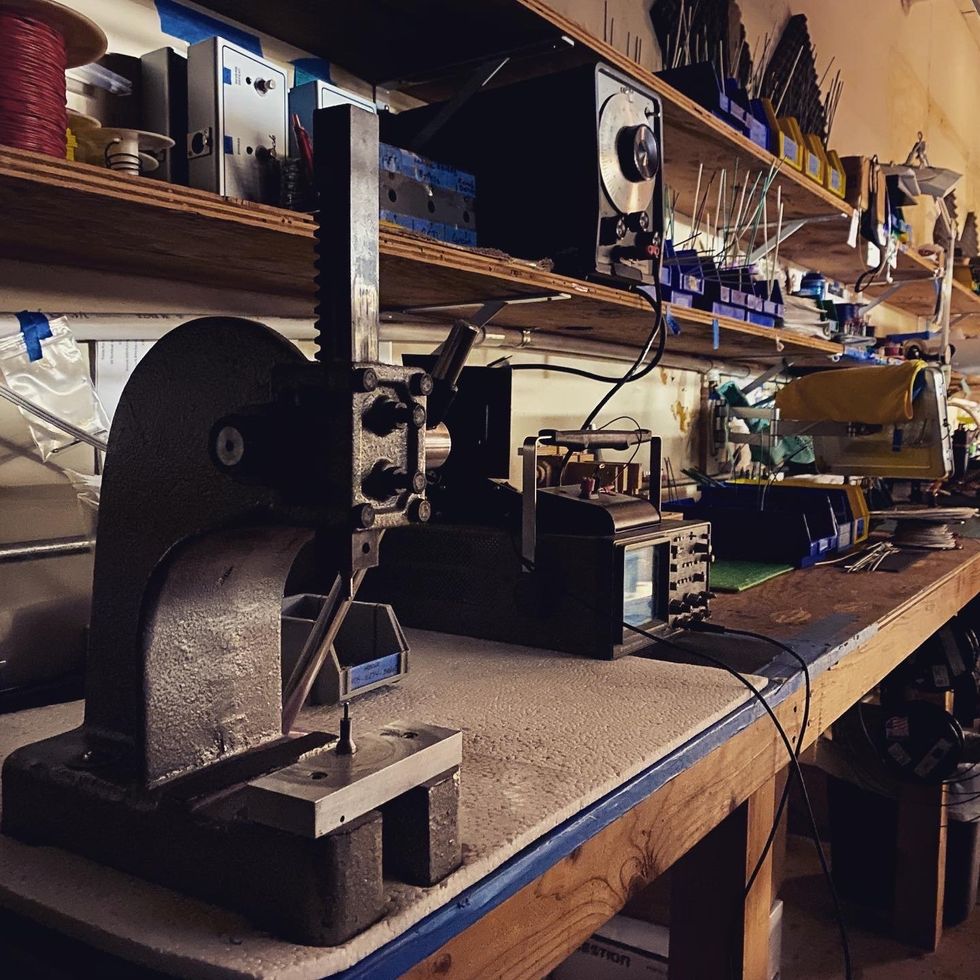

Baggs in the workshop, sanding the side of one of his AEG-1 models.

Baggs admits that he’s not a very good guitar player. He tried learning in college before he got into building, but what really started his career in music was cello, which he began playing in fourth grade. “I wouldn’t consider myself a prodigy, but I was close to one. By the time I was in high school, I was fourth chair in the UCLA Symphony,” he says. “My teacher was Joseph DiTullio, who was then the chief cellist with 20th Century Fox, but was the concert master of the L.A. [Philharmonic] before that. He said he was going to start subbing me on dates that he couldn’t take with 20th Century.”

Outside of his early accomplishments as a cellist, Baggs was a distracted student, more interested in surfing and working on cars than school. Despite his average grades, he ended up being accepted into Occidental College in Los Angeles on the invitation to join their budding cello department. Unfortunately, that plan had an untimely expiration date.

“Within about three months of being in college, I got in a fist fight with the halfback on the football team,” says Baggs, “and I broke my left hand very badly—to the point where I couldn’t even make a fist for almost a year.”

He shifted his studies to fine art and photography, and, after graduating in 1970, began working as a fine-art printmaker in the area. “I worked in a place that did Warhol, Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Sam Francis, [Frank] Stella, [Ellsworth]Kelly—all the big New York artists. At the time, one print would sell for $1,000.”

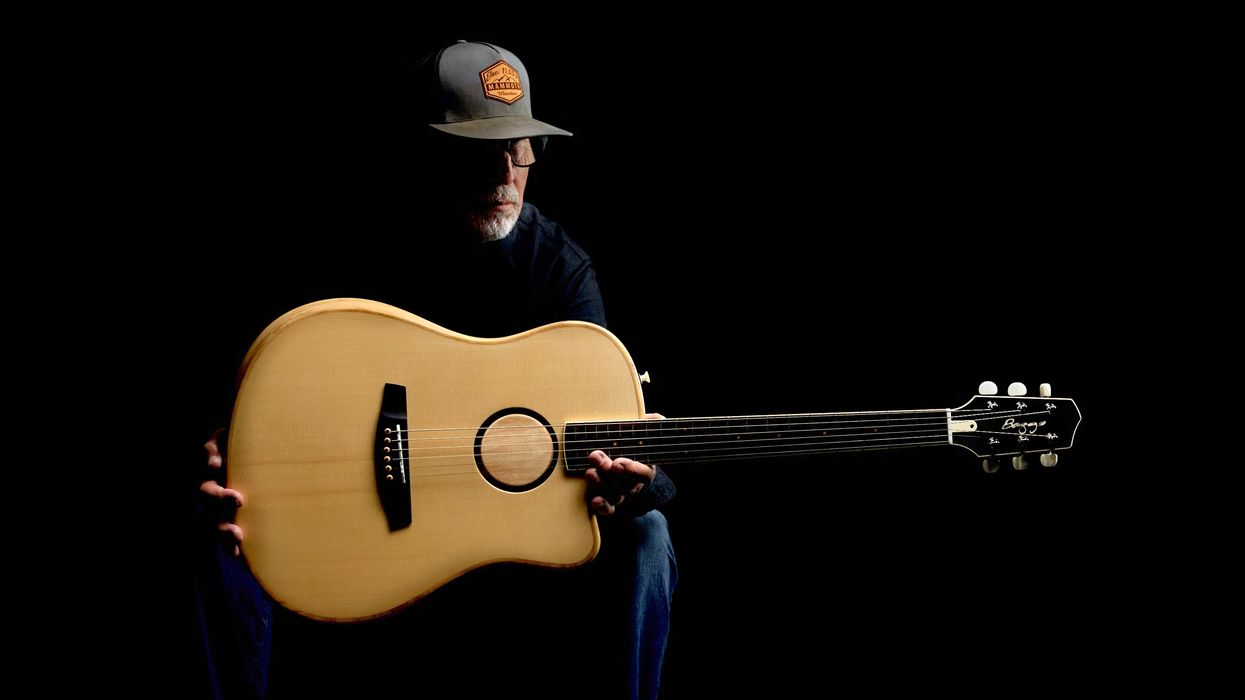

Baggs crafted this custom–built guitar in 1977, for the great Ry Cooder. When Baggs showed Cooder his first polished instrument, the roots-music master said, “I think it’s fantastic. Will you build me one?”

A couple years later, he accepted a master printer position at Editions Press in San Francisco, and would commute there from his place in Berkeley. It was in 1974 that he started building guitars as a hobby, beginning, rather unconventionally, with a copy of a ’30s Washburn archtop with an oval soundhole, thanks to his love for cello and jazz. Around that time—through his connections in the art world—he befriended Ry Cooder.

“Being out doing landscape photography helps me think and organize my thoughts for the business … letting my imagination soar, thinking about anything but guitars.”

“I brought [my first guitar] down to Ry,” Baggs shares, “and just said, ‘Hey, what do you think, man?’ ’Cause he was playing carved-tops and all kinds of crazy stuff. And Ry said, ‘I think it’s fantastic. Will you build me one?’ That launched my career.”

Not long after, Baggs was offered another, more-attractive printmaking job with a prestigious shop in L.A., and moved back, while also building a loft workshop in an old fire station downtown to continue developing his guitar business. After making about seven or eight models, he transitioned to flattops, and his clientele expanded to include Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Janis Ian, and “a bunch of the jazz-heads and flamenco players around L.A. I was getting $3,000 dollars for my guitar, just unadorned, and I had a waiting list of a year or two,” he says.

Meanwhile, Baggs and Cooder had been collaborating on finding the best way to amplify the acoustic Baggs had built for the guitarist. “We’d put all kinds of crazy stuff in there—we mostly landed on a magnetic pickup and a microphone. And hehad this refrigerator-rack-sized gear that he used to swear at and try to make it all work together. I mean, it was brutal! Then, in 1978, he calls me and says, ‘Hey Lloyd, I’m working on an album down at Warner Brothers; you want to come down? There’s something I want you to hear.’”

Here’s a close-up of the simple but highly effective control set on the Baggs AEG-1.

When Baggs made it to the studio, Cooder, who was recording his 1979 album, Bop Till You Drop, surprised Baggs with an acoustic-electric guitar equipped with the best-sounding pickup either of them had heard at the time. The only issue was, the instrument was a Takamine that the Japanese company had designed to mimic Baggs’ exact model, from headstock to strap button.

“I thanked him for showing it to me, left, and I sat out in my car on the street for about a half an hour alternately fuming and excited,” Baggs says, “and that was the moment at which I said to myself, ‘This is where I need to be. This is the future of acoustic guitars.’”

❦

“I still shudder to think about this: I’m driving down the freeway from Santa Monica, in this beat-to-crap old ’59 Chevy pickup truck that I had, with Ry—a national treasure!—sittin’ in the passenger seat; no seatbelts,” Baggs reflects. The two were on the way to NAMM to meet with Mass Hirade, Takamine’s president at the time, to discuss the copy of Baggs’ model.

“I broke my left hand very badly—to the point where I couldn’t even make a fist for almost a year.”

“I complimented him on the guitar,” Baggs says, describing the meeting, “and said, ‘You know, you’ve done a really nice job. But I’m kinda hurt that you didn’t involve me in this in some way, and it does feel like you’ve taken something from me. Don’t you feel like you owe me something?’ And he lowers his head and says, ‘Yeah, we do. What do you want?’

“I said, ‘Well, I build 10 guitars a year. I need to amplify my guitars; will you sell me 10 systems a year? And he said, ‘“Sell” you? Ten systems a year—that’s all you want?’ I said, ‘Yep, that’s what I want. I know you don’t sell that system to anybody, but I’d like to be the guy.’”

A photo of the guitar’s inside reveals its key structural component: a piece of poplar plywood made up of a circular frame of the soundhole, suspended slightly under it by one top section that attaches to the neck joint and two diagonal sidebars that extend to the sides at the guitar’s waist.

Hirade accepted the agreement and, shortly after, sent Baggs two of the Takamine pickup systems to start. With earnest curiosity, Baggs immediately set about reverse-engineering it, approaching the task with his knowledge of car mechanics but with no background in electronics. What he found inspired him to develop something a bit savvier, and soon the LB6 unitary saddle pickup was born.

Baggs’ pickup, which, rather than an undersaddle design, also functions as the saddle, caught on quickly. Several country artists, along with Leo Kottke, were early adopters; Baggs jokes that they could tell where Kottke was on tour by which stores they would hear from when he was visiting. Then, one day, Baggs received a call from guitar manufacturer Robert Godin, who asked if he could use the LB6 in his models. Baggs had to develop a preamp first—at the time, he didn’t know what that was—and his next step was to design a new guitar.

Baggs elaborates, “I was trying to figure out how to sell more pickups, and I thought, ‘I’ll just make an acoustic-electric guitar and put a pickup in it.’ So I bought a Telecaster body from a kit, hollowed the body out on my barbecue with a router, and put an acoustic top on it.”

He also installed some kalimba-like metal rods inside, which, tuned to the main resonating frequencies of a Martin dreadnought, worked with the LB6 to simulate a heightened acoustic quality. The build—Baggs’ second ever acoustic-electric—became Godin’s Acousticaster.

L.R. Baggs AEG-1 Demo

Zach Wish demos the LR Baggs AEG-1. He explores its sonic options and talks about his experience with the guitar on the road with Seal.

But, back to the topic of the AEG-1, and the question posed at the beginning of this article: Why now?

“The word ‘should’ is a very interesting word,” says Baggs, threatening to wax philosophical. “On one hand, ‘should’ should be a four-letter word. Because, it sort of denies reality, and people say, ‘Oh, you should be this,’ or ‘You should be that.’ That’s bullshit. But on the other hand, ‘should’ has this beautiful potential.

“Over the years since the Acousticaster, I’ve kept building,” he continues. “Not building guitars for commercial absorption, but about every couple of years, I would build another acoustic-electric, trying to figure out how to make it sound like a nice guitar.”

It would take a very thorough, deep dive down the rabbit hole to explain everything behind Baggs’ approach to building guitars, but, in short, he’s a devoted fanatic of acoustic physics. “When I built my first guitar, there was one book on building guitars, and the chapter on tone was three paragraphs long,” he prefaces, laughing. In time, he took inspiration from his life as a cellist to pursue what has become a lifelong source of intrigue: studying violin Chladni patterns. His goal has been to harness the information from the symmetrical patterns, which show how a rigid surface vibrates, fluidly, when it's resonating, to improve acoustic guitar resonance. “I would say it’s a fair statement that I was the first builder to start looking into Chladni patterns on a steel-string acoustic guitar,” says Baggs. Now, builders like Andy Powers, Bryan Galloup, Giuliano Nicoletti, and others from around the world attend conferences on the subject, and acoustic physics in general.

The three variations on the AEG-1 in Baggs’ catalog.

Since, Baggs says, “I’ve continued to investigate guitar physics, I’ve continued to investigate Chladni patterns. I’ve gotten more scientific equipment on this thing now [holds up iPhone] than I had when I started looking at building. So, I’ve been trying to figure out how to make an acoustic-electric guitar that sounds really nice acoustically to begin with [before adding a pickup].”

When Covid hit, Baggs found himself with ample free time, and was encouraged by his staff to try building another guitar—for the first time since the late ’80s. His first attempt was to make somewhat of a redo of the Acousticaster, but the results were subpar—at least by his own standards. Thinking the problem might be the air volume inside the shallower body, he took an old acoustic-electric, cut a big hole in the back of the body, and epoxied a “big ol’ kitchen pot” to add air volume. “Didn’t change the sound at all,” he says.

To figure out where to go from there, Baggs drew inspiration from his earlier years as a builder. “I had this conversation with José Ramírez III in Germany in around 1990,” he explains. “He told me that on his top models, he made his sides a quarter-inch thick, like the rim of a drum. He said the more rigid your sides are, the better the guitar’s gonna sound.” Baggs states that’s because of one key fact: An acoustic guitar’s back is an anchor for the neck, holding it straight in place. When the sides are more rigid, the back is freer to resonate.

He decided to experiment with that idea on “a little old China-made 000 guitar,” reducing its depth by cutting it in half, adding wood around the inside of the rim “to make the edges totally rigid,” and gluing it back together. “And son of a gun, if it didn’t sound really good! That’s what led to this guitar.”

A rear view of this natural finish AEG-1 reveals its bolt-on neck base and access panel.

On the AEG-1 product page on the L.R. Baggs website, a photo of the guitar’s inside reveals its key structural component: a piece of poplar plywood made up of a circular frame of the soundhole, suspended slightly under it by one top section that attaches to the neck joint and two diagonal sidebars that extend to the sides at the guitar’s waist. “It’s all cut on a CNC machine; it’s machined out like a bicycle part,” Baggs explains. “So, the neck is actually anchored to the sides of the guitar.” (If you were wondering, that’s why it doesn’t matter that it’s made of plywood. Poplar plywood for the structural component was also chosen for sustainability reasons.)

“You know the second skin on the kick drum, the one that has the hole?” Baggs continues. “It’s very important how you tune that. And we discovered that most people like to tune the kick slightly below that of the main head, so it enhances the low frequencies.

“Then, ‘aha!’ Because the back wasn’t holding the neck anymore, we could do whatever we wanted with it. It was no longer a structural part of the guitar. It was the second skin on a kick drum. So, we just went nuts. That was it.”

I tell Baggs, towards the end of our conversation, that his career trajectory reminds me a lot of the concept of divergent thinking: essentially, about drawing connections between ideas that seem disparate to other people. He says he relates to that idea.

“And that was the moment at which I said to myself, ‘This is where I need to be. This is the future of acoustic guitars.’”

“If it hasn’t been by inspiration, we just simply won’t do it,” he says, “because it has no power; it has no meaning; it has no heart. If it’s just something to fill out a line item in the business … it does not have any authenticity because it doesn’t have any need. And I think that one of the reasons our company’s done so well is that we’ve surrounded ourselves with really talented people. Honestly, I feel a lot like the village idiot most of the time,” he says, laughing.

“I had one of the guys from my L.A. posse visit me yesterday,” he shares. “We were talking about creativity, and I remember saying to him that just about anything that anybody does that’s great doesn’t make any sense. It’s not contrived for a purpose like making money. It’s just something you have to do … like absorbing oxygen in your body. People that paint, people who do music—we’re kind of freaks! People say, ‘Oh, you’re so courageous to have started the business.’ Nah-ah,” he says, emphatically. “I was not cut out for anything else! I would suffocate in a suit!”

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)