Though they’ve been part of the electric guitar

scene for nearly half a century,

stompbox builders have always had

something of a reputation for being odd outsiders,

maybe even a little romantic—in that

garage-entrepreneur kind of way. Luthiers? It’s

easy to imagine them as crabby old cobblers

and cabinetmakers, clad in overalls, bifocals,

and tweed. But pedal makers—they’re a cross

between some Manhattan Project dropout and

a greaser chopping a ’49 Mercury on the front

lawn. A little bit weird, an affront to the status

quo, and most certainly up to no good.

Like any legend, it’s partly true (just have

a look at some of the oddities among the

30 pedal reviews elsewhere in this issue).

But for all its fringe tendencies, the world

of independent and boutique stompbox

builders is fast transforming into a brave

new world of refined craft, high technology,

creatively applied engineering, and

soundscapes yet unexplored. And, ultimately,

the transformation is a boon to

us, the players. Because whether a pedal

is designed to capture the unholy fuzz of

some all-germanium obscurity made for

three days in 1967 or help us make wholly

original sounds, boutique builders are

helping guitarists be more expressive and

creative than ever.

The five stompbox builders profiled here

are among the most inventive and respected

in the trade. They are certainly not the

only innovators in the pedal industry, but

they represent a cross section of the traditionalists

and the tweakers who continue

to make our artistic and tonal pursuits

an adventure.

Strymon

Red Witch

Mad Professor

Crowther Audio

Empress Effects

e

Strymon

|

Strymon effects is the brainchild of founder

Terry Burton, but the Westlake Village,

California, company runs on the collective

power of an engineering brain trust—a

gang of self-declared “left-brain artists”—

that, in some ways, represents a shift

toward acceptance of digital in the boutique

marketplace. Because, unlike many

boutique pedal houses, Strymon enthusiastically

embraces digital signal processing

(DSP) technology. While scorned by some

analog purists, DSP enables Strymon to

create some of the most authentic vintage

sounds available to guitarists.

Strymon’s DSP pedals—the Blue Sky

Reverberator, the Orbit Flanger, the Ola

Chorus & Vibrato, and the Brigadier Delay

(all reviewed in the July 2010 issue of PG)—

have drawn raves for their approximations

of analog sounds. And the company’s latest

pedal, the El Capistan (see the review on p.

182), may be the most refined realization of

Strymon’s aspirations—a processing powerhouse

in a pedal that can simulate the fuzzy

warmth, irregularities, and imperfections of

tape delay and transport the user to truly

bizarre sonic realms that only complex digital

processing makes possible.

Strymon’s Dave Fruehling holds the title of

Firmware Architect Genius.

Strymon’s analog engineer, Gregg Stock, explores old-school ways with a

heavily modified, Floyd Rose-equipped Gibson Explorer.

Strymon founder Terry Burton with an SG and a Brigadier delay (foreground).

|

Burton was just a teenager when he caught

the pedal bug. And like most builders, he

was blown away by the sound of the analog

classics—in his case, a Thomas Organ-built

Crybaby wah and an A/DA flanger that

would ultimately inspire the Strymon Orbit.

“My uncle let me borrow his A/DA

Flanger, Crybaby, and a Yamaha SPX90,

and I abused the privilege by taking

everything apart and reassembling it at

least 20 times in an attempt to find out

how things worked,” explains Burton. “I’m

currently still ‘borrowing’ the A/DA and

the Crybaby after many years.”

Burton’s abuse of the Yamaha SPX90 may

have opened his mind to the potential

of digital circuits as he was falling in

love with analog sounds, but he was also

inspired by some distinctly contemporary

sounds overlooked by many pedal

hounds: Andy Summers’ modulation and

delay on Police records, the modulation

sounds achieved by the Pretenders and

the Cure, and the aggressive guitar-straight-

into-amp tones of Fugazi. That

wide perspective on musical history—and

the open-mindedness about what defines

a great tone or great record—is a big

part of the Strymon design mindset.

“Obviously, delay, reverb and modulation

all existed before we started making our

own. Sometimes we try to take existing

effects into uncharted territory and sometimes

we are trying to solve a specific

set of problems that existed in analog circuits,”

says Burton.

“When we developed the Brigadier Delay,

we knew that the nicer, high-voltage analog

bucket-brigade chips were nearly impossible

to get and that all analog delays

suffered from certain problems like poor

signal-to-noise ratios, distortion, and limited

headroom. Of course, these ‘problems’ are

part of what make analog delays cool,”

Burton admits. “So we implemented discrete

bucket brigade stages in DSP and

added a control for ‘bucket loss.’ That

single control lets you have a cleaner analog

delay than has ever existed before or a

very dirty and noisy one. With El Capistan,

the goal was to capture all of the electrical

and mechanical nuances that make classic

tape delays sound the way they do—and

put that technology in a small form factor

without the maintenance nightmares that

plague traditional tape delays.”

Burton and his team understand why players

treasure analog sounds. But unlike many

players who have chosen sides along the

digital-analog divide, Burton sees digital

as a way to look backward and forward

simultaneously. “I think the analog fixation

that many players have is not unfounded,”

Burton says. “And there certainly have

been many digital products released over

the years that have failed to deliver the

goods. We are keenly aware of this when

undertaking our DSP designs. But if we’re

successful in achieving our design goals,

the technology becomes irrelevant. What

we know and love is making hardware, and

we want our hardware to be not only great

sounding, but also fun and satisfying to use.

Traditionalist or not, if someone sits down

in front of a pedal and that pedal inspires

them musically, then it’s a successful design.

My hope is that we’re always using the

authentic sounds as a foundation and building

from there. In addition to making things

that conjure the days of old, we also want

to create sounds that haven’t even existed

before. And, we’ve got lots of projects

cooking in our labs.”

Red Witch

|

The seeds for New Zealand’s Red Witch

pedals were sown when founder Ben

Fulton’s girlfriend bought him a Holden

50-watt amp head in need of work. The

repairs, as well as the need for some effects

to put in front of the amp when it was

healthy again, prompted a fascination with

preamp, amp-modulation, and pitch-modulation

circuits that led to his first effect—the

Moon Phaser. The project was originally

intended for Fulton’s personal use, but his

friends dug the little pedal and the requests

started coming in so fast that a business

was born.

Today, Red Witch’s line includes the Deluxe

Moon Phaser, the Pentavocal Trem, the

Empress Chorus, the Fuzz God II, the

Famulus Distortion, and the Titan Delay.

The motivation behind each of these pedals

is the same that guided the design of

the first Moon Phaser: “The boutique pedal

scene was much smaller eight or nine years

ago, and there were a lot of guys building

clones of classic, out-of-production pedals,”

says Fulton, recalling the early days

of Red Witch. “There were a lot less folks

doing new or innovative stuff. I’ve never

had any interest in copying or cloning other

people’s designs. Manufacturing anything—

your own idea or someone else’s—is a

huge amount of work. So I figured from the

outset that I’d prefer to put my time and

energy into something that was unique, different,

and, most importantly, my own.”

Though he was eager to carve out his own

niche, Fulton knew what sounds he liked on

record. Not surprisingly, Fulton’s list of sonic

influences was broad and varied, ranging

from experimental Japanese guitar expressionist

Keiji Haino to pioneers like Jimmy

Page and Mick Ronson—players that, as

Fulton put it, had “a purity of expression.”

“Page’s palate has had an influence,”

Fulton says. “The range of tones that he

got with guitar, amp, and pedal combinations

in the studio is staggering—layer

upon layer of guitar parts, each with a

slightly different treatment. Beautiful.”

Another Brit was also a huge influence on

Fulton’s sonic philosophy. “I loved Alvin

Lee’s guitar sound, that blistering playing

in the late ’60s—very clear and articulate.

I guess with our Fuzz God II and Famulus

distortion, I really strived to get that clear,

punchy sound happening. No additional

frequencies, nothing that would allow the

guitar to get muddy in the mix.”

Fulton’s interest in not just the specific

pedal tones but the overall playing

approach of the greats keeps him from

obsessing over emulation, which means

he can focus on the flavors that make

his pedals different. It also means he can

refine them to the point of being practical

rather than a gimmick. “I’ve designed

every device to offer guitar players

really useable flavors in the specific effect

genre—and then something totally new

that’s not available elsewhere, but that’s

also totally useable.

“There’s no point offering bells and whistles

that you’d never use,” he continues.

“For instance, our Moon Phaser offers

three different styles of phasing, as well

as a gentle tremolo setting. In addition,

it offers our unique Tremophase—where

the phase shift occurs at the same time as

the tremolo’s volume pulse. No one else

has done that before, and the Red Witch

Moon Phaser remains the only source of

this new, useable sound.”

For all his concerns with practicality, Fulton

also doesn’t mind tinkering with radical

sounds. Though even his pursuit of more

“out” sounds are in the name of musical

ends. “I’ve always loved contrast within a

piece of music,” he says, describing one

of his musical guidelines for design. “You

want to make a section of song seem really

loud? Play really quietly before it. And

vice versa. The Fuzz God can do really

subtle fuzz sounds—but then you can click

one footswitch and enter a world of sonic

insanity. It allows you to shift between two

extremes very easily.”

In the end, Fulton’s concern with musicality

reinforces his own primary directive—staying

creative as a pedal maker so that musicians

can be creative with his creations.

“I think our customers are the players out

there who really pay attention to their whole

approach—playing, tone, and gear,” Fulton

says. “They want the classic sounds but they

also want to push the boundaries. They

don’t just want to emulate their heroes, they

want to develop their own voice.

I try to design stuff to help folks do that. I’ve

never considered whether people use them

to the full extent of the box’s capabilities. As

long as the pedals are helping to open new

creative avenues for them, I’m happy. I think

that’s part of the appeal of our stuff: you can

use as few or as many of the features as you

like. Either way, offering something unique

opens new avenues of expression for them.

I like that idea a lot!”

Mad Professor

|

Finland’s Mad Professor company is just eight

years old, but in that time the company has

built one of the most extensive lines of pedals

offered by any small-scale, independent

stompbox maker. The company is effectively

a partnership between founder Harri Koski,

amplifier specialist Jukka Monkkonen, and

electronics genius Bjorn Juhl, who designs

the company’s pedals.

Koski started Mad Professor after his experience

operating Custom-Sounds, a company

he founded in 1996 to distribute highend

guitar gear in Finland. Custom-Sounds

was also one of the first online boutique

dealers in Europe, and had a web shop up

and running by 1996. But for all his love of

boutique and vintage gear, Koski was still

frustrated with the limitations of much of

the gear he was hearing. Meeting fellow

tone obsessive Juhl led to creating the Mad

Professor CS-40, the amplifier that put the

Mad Professor brand on many guitarists’

radar. Since then, Mad Professor has built

a roster of 12 stompboxes that includes

three flavors of overdrive, a phaser, a fuzz,

an analog delay, a tremolo, and even auto

wahs for guitar and bass.

Juhl still masterminds most of the pedal

designs. He’s self-taught in the ways of

effects building but has worked with musical

instruments since the age of 16 and studied

electronics for 30 years—ultimately drifting

away from his electronic service shop and

into design of his own effects pedals and

products for Mad Professor.

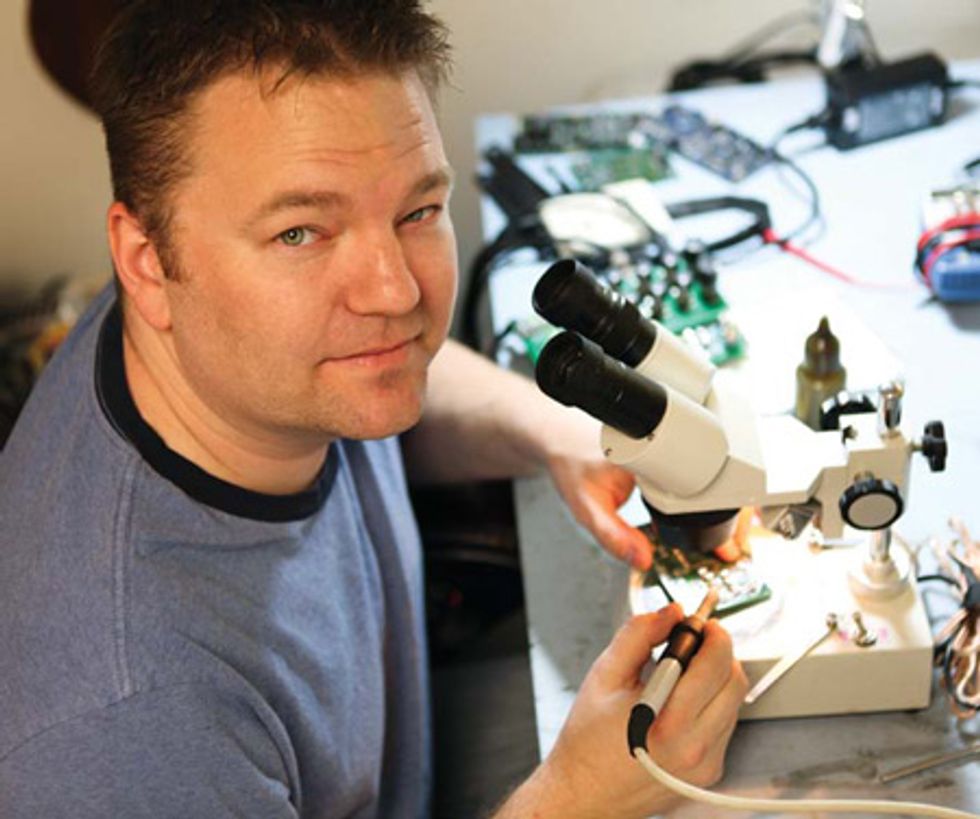

Bjorn Juhl is an electronics autodidact and the principal designer behind Mad Professor’s pedal line.

“If I could have gotten the sounds I wanted

to get at the time, I wouldn’t have bothered

trying to build stompboxes,” says

Juhl, recalling his earliest investigations of

effects. “Back in the late ’70s, I could look

at Electro-Harmonix, MXR, and Boss pedals,

which are all still very good today. And

I also read the excellent book Electronic

Projects for Musicians by Craig Anderton.

But I learned by process of elimination, too.

I built little models of amplifiers to investigate

exactly why certain things sounded

bad and removed everything that sounded

bad until just the good stuff remained.”

Like many of the builders profiled here, Juhl

rejects the notion that the best pedals have

been made—that the stompbox frontier

was conquered decades ago. Tones that

inspired him include Pete Townshend’s Live

at Leeds sounds, Billy Gibbons’ vast palate,

and the aggressive, monster grind of the

Sex Pistols. But he’s always on the lookout

for the ways in which existing pedals come

up short, and listening for sounds he can

imagine but doesn’t hear in the collective

soundscape. “I’d actually say that the

biggest inspirations for me are the most

uninspiring sounds,” Juhl says. “I’m always

trying to figure out why certain combinations

of guitar and amplifier work, why

some really don’t work, and some work just

fine. Because you can change those things

when you’re in the know.”

So far, Juhl, Koski, and the rest of the Mad

Professor team have been successful in

uncovering the little differences that pique

the interest of a sizable number of tonehounds.

Pete Anderson, Jerry Donahue,

Marc Ford, and Jim McCarty are just a

few of the players who have stocked their

quiver with Mad Professor pedals. And

the company remains committed to adding

new tools to their line, including a

forthcoming EQ pedal that found Juhl considering,

among other things, the impressive

bandwidth of Shadows guitarist Hank

Marvin’s tape echoes.

But just as Juhl and Mad Professor look

for inspiration in odd places, they look to

make their products inspirational so that

players will unlock their imagination when

they plug in a Mad Professor box. And

Juhl hopes that commitment will help players

push themselves instead of relying on

gear to solve problems. “Back in the ’70s,

stores had one fuzz pedal and they’d tell

you ‘Take this, son—this is just what you

need.’ Then you’d go home and read Tom

Wheeler’s book where he says there may

be a little more between you and Jimmy

Page than a fuzztone pedal.”

Crowther Audio

|

In the relatively young business of boutique

pedals, Paul Crowther could be fairly

regarded as a grizzled veteran. He built

the first version of his signature pedal,

the Hot Cake, in 1976 while laying drum

tracks with legendary New Zealand prog/punk/new wave unit Split Enz. Perhaps

it was the unique perspective of watching

guitarists struggle with tone from the

drum riser that ultimately drove Crowther

to build the now legendary and revered

Hot Cake. But his investigations were

founded on a fascination with the circuitry

of sound that predated his days as a professional

musician.

“After hearing the Rolling Stones’

‘Satisfaction’ on the radio, I just had to

make a fuzz box,” Crowther recalls. “I

built the first one from a magazine project,

using four germanium transistors. It

had a volume control but no gain control.

That was the first time I ever made a circuit

with solid-state parts. It had quite a

long sustain, but cut off abruptly, because

it used a ‘Schmitt trigger’ circuit—definitely

a one-note-at-a-time unit!”

But even then, Crowther was looking for

ways to address musical needs beyond

what a fuzz or wah could do. “I was playing

drums in a covers band, and we were

learning the Hollies’ ‘On a Carousel.’ I

made a box to give a guitar that resonant,

banjo-like sound in the intro. It had a

six-position switch for different resonant

frequencies, and it used a big radio-choke

inductor. It also had a control for adding

the low frequencies back in. It distorted

just a little bit, too, and our lead guitarist

used it for all sorts of things. I called it a

Herbert Box for some obscure reason.”

When Crowther finally got around to

building the Hot Cake, he’d worked on

tone circuits for everything from wah pedals

to organs. But Crowther ultimately

relied on his ears to perceive the needs

that the Hot Cake addressed—essentially

how to make a guitar signal hotter

and more distorted without sacrificing

the best and most essential parts of the

guitar-amplifier tone equation.

“The initial idea was to make a preamplifier

circuit where the undistorted component of

the sound has a flat response, but where the

distorted component has reduced high frequencies.

The overall effect of this is to make

the sound spectrum of the distortion similar

to the guitar sound. I think it has always been

popular because guitarists find that their tone

doesn’t radically change when they switch

in the Hot Cake. It also handles chords quite

well and has low self-generated noise.”

As the slow expansion of Crowther’s product

line illustrates, he pursues a new design

only when he’s interested or perceives

an opportunity to fill a hole that other

stompbox makers haven’t. Such are the

origins of the Prunes & Custard, a harmonic

generator-intermodulator (many mistake it

for an envelope filer) that has found many

fans among bass players and adventurous

guitarists like Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy.

“I wanted to make something that didn’t just

clip the waveform, but was more interesting,”

says Crowther. “With the P&C, which

I first made in 1994, the waveform doubles

back on itself, amplitude-wise, a few times. I

have since heard about a synthesizer module

called a wave multiplier, which does something

similar—although I did come up with

the P&C circuit quite independently.”

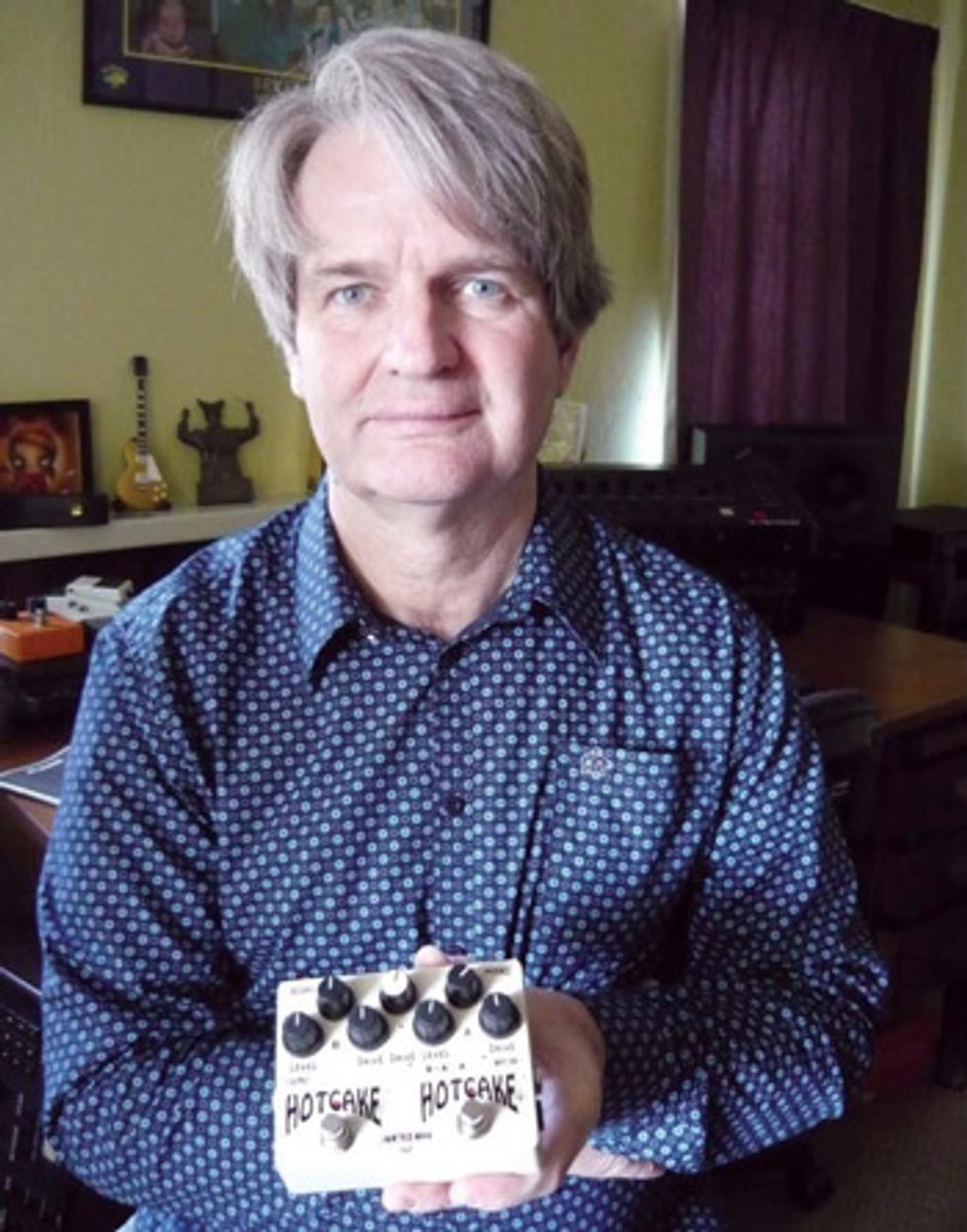

More recently, Crowther introduced the

Double Hot Cake to address the needs of

players that use multiple overdrives to expand

their tone palette onstage—particularly those

using two Hot Cakes. In typical Crowther

fashion, however, the Double Hot Cake adds

dimension that a simple two-overdrive setup

could not. “I finally came up with the idea

of an arrangement where, when both Hot

Cakes were switched on, Hot Cake A would

drive Hot Cake B, but Hot Cake A’s controls

would have no effect, and A’s Drive would be

controlled by an extra Drive pot. I also added

an extra clipping stage in between A and B, so

that it goes a little bit into fuzz world and adds

an extra mid boost. Hotcake A is the slightly

less edgy ‘bluesberry’ version, while B is the

normal old circuit.”

Like any good engineer (or drummer, for

that matter), Crowther doesn’t come off as

sentimental about a so-called Golden Age

of stompboxes. He likes what works, what’s

useful, and what makes more interesting

music. He does, however, see good analog

circuits as a ticket to achieving a more musical

signal chain. “There is something rather

appealing about a fuzz circuit that uses

germanium transistors. And there is also

something quite subtle in the nonlinearity of

a tube that makes for a less clinical sound.

I believe it produces a very subtle intermodulation

distortion that can help bring the

sound of an electronic instrument to life.”

One also gets the feeling that Crowther

may have a few surprises up is sleeve yet. “I

did try to make an electronic Leslie in 1973.

It was not too successful, but it sure made

for an interesting tremolo. There could be

something there. And there are a few other

ideas spinning around in my head.”

Empress Effects

Our interview with Steve Bragg of

Empress was made possible because

Bragg had just blown up a converter for

a new analog delay. Such is the life of a

stompbox builder pushing the envelope.

Empress Effects—which manufactures the

Superdelay (which won a Premier Gear

award in our November 2009 review), the

Vintage Modified Superdelay, and the Tap

Tremolo in Ottawa, Canada—is another company

that’s carving out new territory in the

high-end stompbox realm by wholeheartedly

embracing digital technology while maintaining

an appreciation for what made early analog

circuits sound so good.

Like scientists amalgamating the best of old and new technologies, the Empress gang—(left to right) Mike Stack, Jason Fee, Steve Bragg, and Dan Junkins—embrace digital processing to extend an effect’s potential in

ways analog circuitry alone cannot.

Unlike some builders, Bragg didn’t fall in

love with any particular pedal in his formative

years. He was more interested in

pedals as a means for learning the way

electronic circuits work, and he gravitated

toward making effects for keyboard players.

He did, however, love the way certain

songs and records sounded. And his first

pedal—a sort of syncopated tremolo that

ultimately found its way into the Empress

Tremolo—was inspired by the song “Vow”

by Garbage.

“I love the idea of combining electronic

and acoustic components, using drum triggers,

having one instrument affect another,

or having effects sync to tempo,” Bragg

says. “There’s a bunch of bands I listened

to growing up—like Archive, Radiohead,

Björk, My Bloody Valentine, and Garbage—

that do that kind of stuff really well. Jonny

Greenwood from Radiohead continues to

be a big inspiration.”

That contemporary frame of reference

may have released Bragg from the baggage

that keeps many analog devotees

unwaveringly in the anti-digital camp. He

readily embraced the possibilities afforded by

having analog circuits and digital processing

working in concert to enhance a guitarist’s

potential. “I really like the idea of having an

analog circuit controlled by a microprocessor.

This makes a bunch of interesting stuff

possible: tap tempo, presets, programmable

triggering, arbitrary waveforms, and completely

new effects that would be impossible

or really difficult with a purely analog design.”

Apparently, many forward-thinking guitarists

agreed with Bragg. “After releasing the

Superdelay, I got a lot of requests to add

mods so it could work with other gear,” he

explains. “Some people wanted to use CV

[control voltage] to control it. Some people

wanted to use relays to control the tempo

instead of the tap stomp switch. Some

wanted MIDI controllability. Unfortunately,

there’s not enough room on a pedal for a

lot of jacks. So we’ve been working for the

past two years on a control port that will

accept a bunch of different inputs: mechanical

switches for remote tapping, expression

and CV inputs, MIDI, and audio input. It’s

been a pain in the ass, but it’s finally all

working. Our first pedal with this control

port will be the Empress Phaser, which we’ll

be releasing sometime soon.”

Bragg and Empress’ open-minded stance

extends to the components that go into their

pedals, as well. They refuse to be constrained

by the emphasis on older components and

instead go with parts that last and sound

best. “We designed our pedals to be as clean

as possible,” Bragg says. “That means using

op-amps, for the most part, and staying away

from transistors that can create headroom,

noise, and impedance issues in the audio path.

I see a lot of funny hype in effects marketing

material, where Teflon wires, expensive capacitors,

gold-plated PCBs [printed circuit boards],

and carbon-composite resistors or 1 percent

resistors are touted as audiophile. I have

serious doubts as to whether these kinds of

things affect the sound in an appreciable way.”

The same emphasis on clarity and quality

makes Empress less concerned with emulating

revered stompboxes, even though they

regard many classic pedals as benchmarks.

“We’ve never been too concerned with

recreating what another pedal can do. But

if we make a pedal with a lot of features,

we want to make sure its basic sound is

as good as the standard go-to pedal. For

instance, when designing the phaser, we set

out to make a pedal that could do stuff no

other phaser could. But if it didn’t sound as

good as an MXR Phase 90, then we’d have

a problem.” Even so, Bragg says, “I think it’s

dangerous to design with someone else in

mind. Instead, I just pretend that I’m a really

creative musician—I know, it’s a stretch!—

and I ask myself what kind of stuff I would

need to make interesting sounds. So far, I

think we’ve only scratched the surface.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)