|

|

For fans of Gibson guitars, there are a few names in the company’s long history that are revered. The most obvious is Orville Gibson, the eccentric founder of the company, who, without any woodworking experience, designed and built some astonishing mandolins, guitars and lyre guitars around the end of the 19th century. There’s Lloyd Loar, who came to Gibson in the early 1920s with an engineering background and made some remarkable revisions to Gibson’s lines. In fact, Loar’s place in Gibson history is so significant that his signature in an instrument from his time period makes it worth tens of thousands of dollars more than the same instrument without his signature.

You’ve also likely heard of figures like Seth Lover, who invented the humbucking pickup in 1957, and Ted McCarty, whose direction in the early fifties led Gibson to its commercial pinnacle. And then there are the people who are known by a devoted minority who kept the Gibson name and reputation alive as the brand expanded and matured. James “Hutch” Hutchins was instrumental in keeping the sixties’ way of producing Gibson archtops alive in the seventies, eighties and nineties – his recent retirement has left a sizable void in Gibson’s archtop production world and has kept the fish in Lake Michigan trembling in fear.

Ren Ferguson falls into this latter category; while he keeps a low profile, he is primarily responsible for some of the most elaborate flattops to come out of Gibson’s Bozeman, Montana plant – officially titled “Gibson Guitar Montana Division” – and arguably for some of the most elaborate flattops in the world.

That may seem like hyperbole, but it’s not. Gibson dealer, Mike Fuller, of Fuller’s Vintage Guitar in Houston says of Ren, “He is simply one of the greatest luthiers of all time. His guitars will be sought after for a long time to come.” Likewise, Dick Boak of Martin Guitars in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, says of Ferguson, “Ren has been our friend for several decades and we have great respect for him as a luthier and as an individual. We have let him know on several occasions that there might be a position here for him, but he loves Montana too much to leave it.”

“I revere Ren as a superb craftsman,” says Mike McGuire, director of operations for Gibson’s Nashville plant. “Plus, he is just a great guy.” Comparisons between Ren Ferguson and Lloyd Loar are frequent and well deserved. Both Loar and Ferguson have taken big liberties with the design of Gibson instruments, and both men placed intense scrutiny on the physical structure of the instruments they revised. Loar changed the bracing inside the F-5 mandolin from a single cross brace in the round soundhole version to two vertical, parallel “tone bars” or braces in the the revised F-5.

Additionally, Loar changed the openings to F-holes on the F-5 mandolin, the K-5 mandocello, the H-5 mandola and the L-5 guitar. Ferguson, on the other hand, took LeRoy Parnell’s 1930s L-00 to a chiropractic office to have an X-ray taken of its bracings so he could understand just what made it so special of a guitar.

“I’m really flattered by the [Lloyd Loar] comparison,” says Ren. “Loar brought a engineering background to Gibson and I brought an experience background with me. We are both musicians, too.”

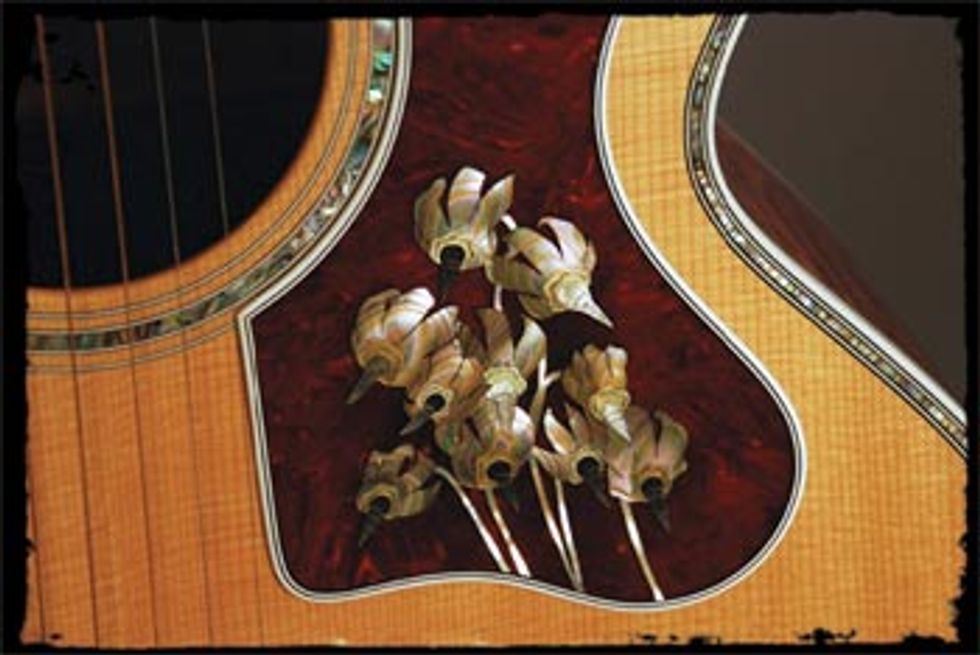

The praise for Ferguson’s work isn’t just limited to those within the guitar industry. Between 500 and 600 orders come into the Bozeman plant annually with a request for Ren’s signature on the label inside the soundhole. Ren is glad to oblige because his signature is now in such demand that it helps sell guitars from Gibson Montana. Perhaps modern day investors are speculating that the value of the Ren Ferguson period at Gibson Montana will equal or exceed the Lloyd Loar period of Gibson in the twenties, but what is certain is that guitar investors are betting on the future. In the years to come, the time to do the elaborate inlay Ren does, and the materials used for that inlay, will become more scarce. Solid abalone is hardly ever used anymore, so Ren’s involvement not withstanding, these “Master Museum” models, as Gibson calls them, will definitely appreciate in value for years to come.

The Beginnings

Ren was originally born Lawrence Ferguson on February 26, 1946, in Detroit, Michigan. As was family tradition on his father’s side, all first born males were to be named after their paternal grandfather – in this case, Ren’s grandfather, Lawrence. Not a big fan of the nickname “Larry,” Mrs. Ferguson intervened, instead giving him the nickname, “Ren,” after a favorite artist. “My mother, who had been an artist at Disney for a while, had a great admiration for an airbrush artist named Renwick,” he recalls.

Ren began his luthier career, as it were, in shop class at Westchester High School, in Westchester, California. By the early sixties Ren had a Harmony guitar and his brother had a banjo – both rather poor excuses for instruments. Ren decided he could make a banjo in shop class for his brother. “I had no idea how complicated instrument building was back then,” he says. “I soon found out how critical tolerances had to be for frets and bridges and the like.” Ren’s father had a furniture business with a spray booth in it, and he got to experiment with refinishing wood furniture that people would trade in – in addition to plenty of Nocasters and Telecasters. “I ruined a lot of potentially expensive guitars back then,” Ren recalls.

While arthritis in his left hand has made things more difficult, Ren continues to do much of the inlay work in Boseman.

Later in high school he took a job selling guitars at a local music store, Westchester Music, which is now part of the runway at LAX airport. Westchester Music was a big store with a large record department in those days; they offered lessons on piano, organ, guitar and most any other band instrument. The store had a large rental department, and Ren was kept busy. “I learned a lot about what it takes to keep band instruments in service,” he explains. “The airport would break about one guitar a day, and they would ask us to replace the instrument or repair it. Often the passenger would sell me his broken guitar or even give it to me after being reimbursed by the airport for the damage – I had a big stack of guitars from airport passengers. Back in those days it was easy enough to get a brace from Martin or a neck from Gibson.” Ren cut his luthier teeth learning how to rebuild these broken guitars before taking a brief hiatus from Westchester to sell Dobros for the Dopera family. “I would hustle Dobros on the street, in clubs or wherever there were musicians I could demo the instrument to. I even designed a thin profile Dobro we called the ‘Californian,’ which was going into production about the time that the company was bought up by Mosrite and Buck Owens and ultimately moved to Bakersfield,” he says. Eventually he set up classes teaching guitar and mandolin building in California before being drafted. While in the Navy he met two brothers, the Millers, who kept telling him how beautiful Montana was; soon after his discharge from the Navy in February of 1969, he traveled to Montana for his first Mountain Man Rendezvous, an event where men cavort as rugged outdoorsmen from days gone by.

“I still wonder what would have happened to me financially if I had stayed in California and built guitars, instead of coming up here to Montana to eat dirt and chew grass,” he says. Ren wonders if he would have had Bob Taylor’s place in history as the premier California guitar maker.

Montana and Mandolins

Ren eventually moved to the Bozeman area in the mid-seventies to make gunstocks for Shiloh Sharps and to do some trapping. He was playing music in a church band and was at his minister’s house when he got a call from Steve Carlson, the owner of the Flatiron Mandolin Company. Steve had already decided he wanted to hire him. Ren explained that he was pretty busy with other things when Steve said, “I’ll pay you $1800 a month,” to which Ren replied, “I’ll see you in the morning.” The Flatiron Mandolin Company made very good mandolins – as good or better mandolins than Gibson’s, in fact. The main difference between the two resided in the neck joints. While traditional Gibson mandolin neck joints had been dovetails, Flatiron changed them to a mortise and tennon neck joint, partly because of the ease of construction and partly because they had had success with the joint in other applications. They eventually got so good at making mandolins that they had more than they could sell. “We were completing about 12 instruments a week,” Ren recalls. Flatiron was also making a handful of banjos and bouzoukis, and was a fairly popular brand among knowledgeable players when Ren joined the company.

| |

|

The next morning, as Juszkiewicz toured the NAMM floor, he came upon Steve Carlson and the Flatiron Mandolin Company. Carlson handed Henry a brochure, when Henry informed him that he was working on behalf of the “new Gibson,” and that as CEO of the new company, he was being put in the unenviable position of being forced to protect the company’s designs. Carlson retrieved the brochure from Henry’s hands and said, “I guess you have to do that,” before walking away.

Three months after that fateful meeting, Carlson finally received a cease and desist order from Gibson’s lawyers, claiming that Flatiron had compromised the “silhouette” of the company’s F-5 mandolin. It was a stunning blow to the company; crippled by not being able to make F-5 mandolins, Flatiron quickly found itself in financial trouble.

Mandolin Brothers, located in Staten Island, New York and founded in 1971 by Stanley Jay and Hap Kuffner, was at that time beginning to deal in new mandolins and had been one of the first vintage instrument dealers to hang out a shingle, perhaps second only to George Gruhn in Nashville. Having been a Flatiron Mandolin dealer for ten years before Gibson’s cease and desist order, Jay became concerned about the future of the small company. At the following NAMM show in 1987, Carlson ran into Jay and they began talking about the situation. Carlson said, “What sense does it make for [Henry] to spend all that money on lawyers to try and put us out of business? He could buy our company for less than he would spend on legal fees.”

| |

|

Shortly after the acquisition of Flatiron, it was decided to move the acoustic production off the floor of the Nashville plant to facilitate Les Paul production. The machinery that was left from flattop production was shipped on semi trucks to the plant at Bozeman. There were only a few usable machines from Gibson Nashville; needing more resources, Carlson bought two flatbed trailers full of tennis racket making machines in Colorado for the paltry sum of $3200. “We basically melted down the aluminum and made a side bending machine from the tennis racket machines,” Ren says. Over time, Carlson was put in charge of building a new facility and Ren took over making fixtures and jigs to facilitate guitar making.

Early in Ren’s building career, he possessed a romantic idea about the guitars he and the Bozeman plant make. He believed there were “unwritten songs” inside each and every guitar.

The Mindset

Early in Ren’s building career, he possessed a romantic idea about the guitars he and the Bozeman plant make. He believed there were “unwritten songs” inside each and every guitar, whether it ended up with a teenage girl playing only for her cat, or in the hands of Emmylou Harris, playing in front of thousands nightly.

New ownership meant new changes. One of the most difficult mindsets for Ren to adopt came from a meeting with Henry. Henry told Ren, “Don’t over-romanticize the making of these guitars – they are just boxes, for crying out loud.” Ren took Henry’s words to heart and over a period of time finally understood that even if they were making apple crates, they needed to make the best, most durable apple crates they could. They also had to be made with the least amount of materials, in the quickest way possible and in a way that makes a profit for the company. Ren admits that this was eventually an epiphany for him. “Henry wants us to make the best sounding guitars that never come back,” he says. “We are all just sharecroppers of the Gibson tradition. We get to get up in the morning and come make the best guitars in the world.” And it seems that every employee in the Montana plant feels that same duty; when visitors tour the Bozeman plant they are frequently impressed at how “heads down” the entire staff is. They are focused on making guitars; their collective attention to detail and dedication might be compared to a colony of bees. “No one is lounging about here,” Ren says.

That dedication and singular focus has paid off. There are numerous buyers around the globe who are waiting in the wings for Ren Ferguson’s next “Master Museum” guitar, and they are willing to pay upwards of $50,000 just to own one. “They don’t sound any better than the standard J-200s,” Ren surmises, “but they sure don’t sound any worse.” When asked about how he felt the high prices his creations were fetching he replied, “They are a stone bargain. What if you paid a master plumber for the 200 hours of work he had done on your house?”

| |

|

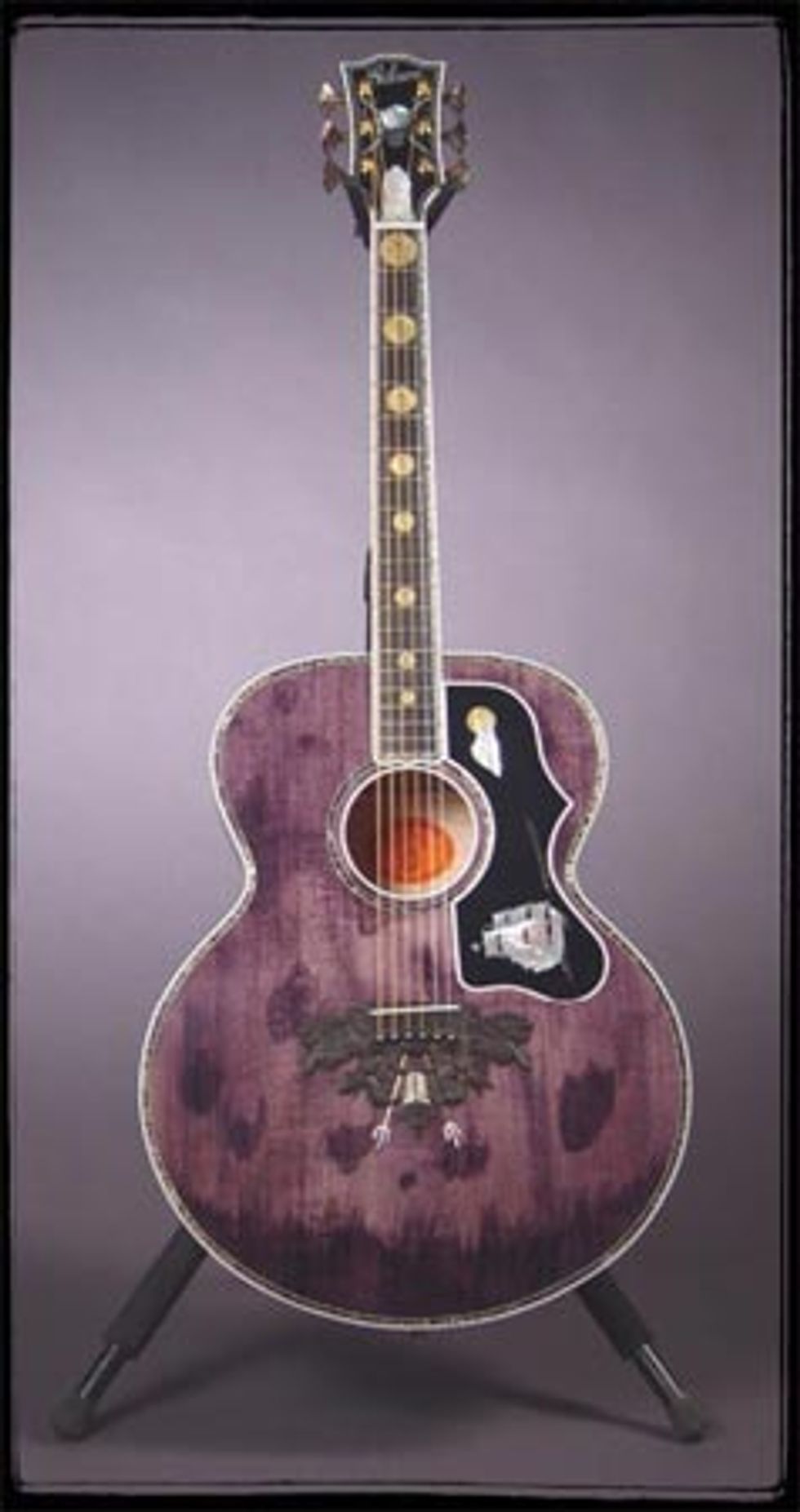

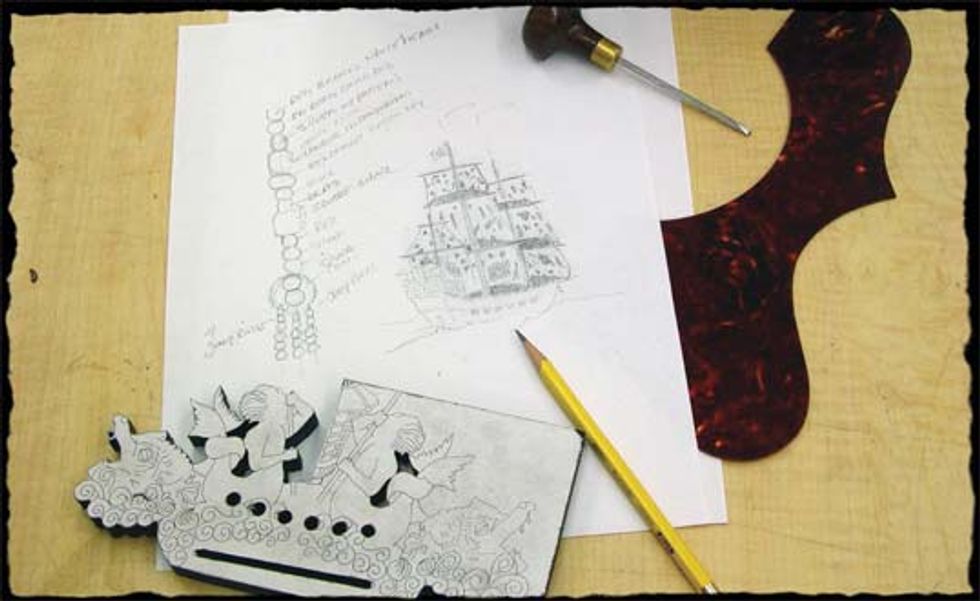

He recalls the intense labor he put into the “Pirates of the Caribbean” J-200, which was built for Johnny Depp in honor of the movie, which Ren admits he was slightly obsessed with. That obsession came about from a line in the movie, where Depp is marooned on an island and begins reminiscing about his ship. Depp says, “A ship is more than a keel, a hull, a deck and sails – what it is is freedom.” The line struck a chord with Ferguson, who believes that a guitar is more than just spruce, mahogany and some lacquer; it is also freedom.

Ren’s son, Matt, played a band with some folks from Disney and began talking about the guitar his dad was designing – this led to visits to the set of the movie for Ren. Photos of Depp on the fantail of the ship were supplied by Disney and were eventually carved into the guitar’s ebony bridge. Coins were procured for the fret inlays. The guitar was made from close-grained spruce and quilted maple and finished in a shade of purple that was transparent, but had veils of opacity as well. The finished guitar was purchased by Disney for an undisclosed sum – it is reportedly valued at $100,000.

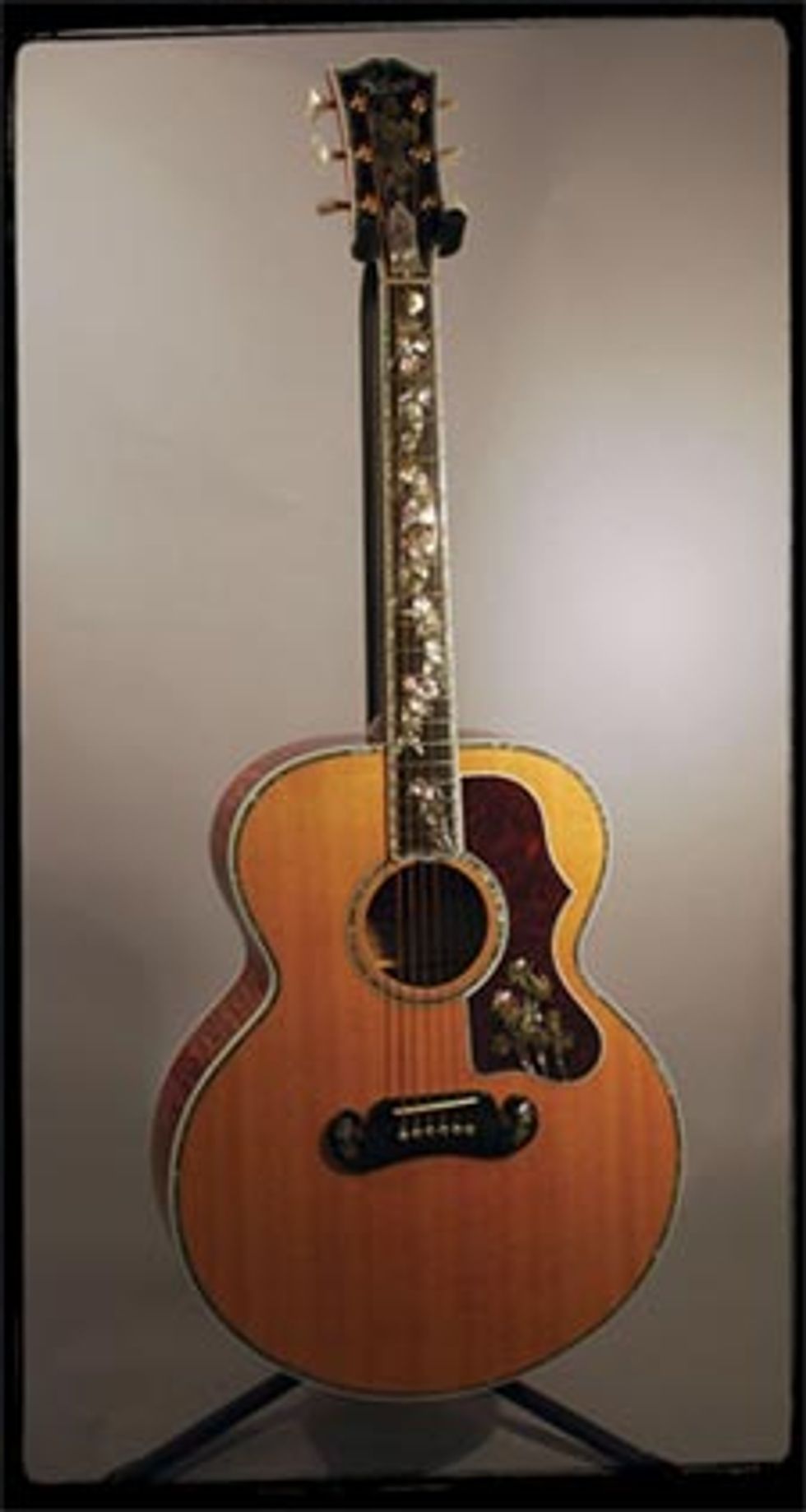

Most of the “Master Museum” collection – his most valuable and collectible creations – is comprised of J-200 body styles. It’s a model that has had a special place in Ferguson’s heart for a number of years, since he ordered a Gibson J-200 from the music store he worked at in Westchester, California. “It didn’t come in for over a year,” he recalls. “I ordered a sunburst and the guitar came in pasty white.”

The Plant

Ren Talks Wood We asked Ren about the woods he prefers building guitars with; he told us his ear prefers the sound of red spruce and Brazillian rosewood. However, considering there will be no more Brazillian rosewood guitars coming out of Gibson, due to the company’s new focus on preserving endangered woods, he has been forced to develop some good-sounding alternatives. We asked Ren to tell us how he approaches three of the most popular types of woods, and what he typically hears in guitars built with them. Mahogany “It’s friendly – it holds on to the chorus notes really well and gives you this back-filled sound. If you pick with your fingers, you can get great clarity. Ragtime and blues can be played on mahogany and sound perfect.” Rosewood “It seems to sound a little bit darker. Rosewood is harder to set in motion – the reflective sound and energy required to set it in motion are a little more substantial. Rosewood has a richer tone than mahogany, a more enduring sustain and a sweetness, but perhaps not excitement of a mahogany instrument.” Maple “Maple is clean and clear and holds the midrange incredibly well. It projects really well. Maple may not have the sustain of rosewood or the “party” sound of mahogany, but maple may project more or seem louder than any of the other woods. Eastern U.S. maple tends to be a bit denser or harder than its western counterpart; quilted maple is the softest of the lot. You will get more punch from the eastern flame woods, but more warmth from the western variety.” |

The Bozeman factory is located on a street conspicuously named Orville Way, and is nestled in a pristine valley situated between the Gallatin Range and the Bridger Range, named after mountain man, Jim Bridger. Bozeman is a relatively small town of approximately 30,000 inhabitants. According to Cindy Andrus of the Bozeman Convention and Visitors Bureau, “Bozeman is not easy to describe to someone who has never been here before. It is one of the most diverse small towns in the Western Rockies. It is blessed with an eclectic mix of ranchers, artists, professors, ski enthusiasts and entrepreneurs, all of whom are drawn here by world class recreation, Montana University and a slice of old fashioned Americana. There are hundreds of scenic vistas nearby and Bozeman is a mere 90 miles from Yellowstone; all in all, the area lures visitors from around the world.”

It’s definitely an environment that inspires creativity. Many, if not all, of the new models coming out of the Bozeman plant are Ren’s designs, including the Songwriter series, the Doves in Flight, the J-2000 and the Monarch; they all have their beginnings in his imagination. There’s really no limit to the lengths Ren will go to develop the perfect design. He went as far as packing several models of Gibsons, Martins and Taylors full with wheat to measure the volume of each instrument and to determine the best “recipe” for the production of each of the limited vintage reproduction Gibsons he was making. In his quest for the best sound he has determined that all Gibson flattops have had an inherent 28-foot radius, or parabolic convex shape, incorporated into the top. This keeps the pent-up energy countersprung so when the strings are plucked the sound is immediate and forceful.

When asked how he gets his ideas and inspiration for his gorgeous inlay work, he responds, “I am a great thief!” Having gotten ideas from coffee cups, wallpaper and clouds in the sky, he steals them all. He has always seen things that others have missed. He recalls waiting in the doctor’s office and seeing patterns in the linoleum, in the carpeting. As a kid he was always whittling a neckerchief slide or making a Jiminy Cricket out of oldstyle clothespins. “I have always seen things that weren’t there to be seen,” Ren says.

Although he does enjoy making fine, high-end instruments like the "Pirates of the Caribbean" guitar, he says his favorite guitar is the next one he is getting ready to build.

As time has passed, Henry Juszkiewicz has realized what a golden goose he has in Ferguson. Having consistently made good products out of something as variable as wood, Ren has been given the unprecedented opportunity to remake any and all models of the acoustic guitars produced at the Bozeman plant. A recent production of Hummingbirds made with fine quilted maple is just one example of the freedom afforded to Ren. When Gibson is considering a reissue, they will get numerous examples of a certain guitar and compare them extensively; they will then pick the instrument that has the best tone, feel or “mojo” of all the examples.

| |

|

The research has not simply revolved around finding ways to efficiently recreate Gibson’s past classics; the Bozeman crew is busy finding new ways to advance the acoustic. For instance, Gibson Montana has refined the tops on its new instruments with a counter tension to the strings – “pent up” tension, as Ren calls it – so when a note is struck, the top immediately comes alive. It’s not like bumping a table and having a book fall off the other end; it’s like bumping a table and having the book shoot off the other end. “I don’t have time to wait around for my guitars to sound good,” Ren states rather pragmatically.

When asked if he would prefer more or less automation in guitar building, Ren’s response was somewhat surprising – although not as much if you recall his epiphany from Henry. He would prefer to see more automation as long as the final product is unaffected. “If I can prevent my workers from getting a repetative injury from sanding wood all day long, then you bet I am for the automation,” he says. The plant has already automated some tasks that were considered hazardous or “life-threatening.”

The Future

You would think that Ren would be salivating over the opportunity to do some fancy inlay or carving at this point in his career – his skills have developed so impressively, and his work is commanding such a premium, that it would seem silly not to. Surprisingly enough, Ren says that while he enjoys inlay work – something he says he “has to do,” like an artistic compulsion – but he is more thrilled by the overall production of instruments. Although he does enjoy making fine, high-end instruments like the “Pirates of the Caribbean” guitar, he says his favorite guitar is the next one he is getting ready to build. He has no puffed up ego, no self-serving idea about his well earned reputation – he is, in fact, the ultimate team player. If you know any extraordinary plumbers, you know that at the end of the day they still have to clean their fingernails themselves; it is refreshing to know an extraordinary luthier with the similar attitude.

“We want each guitar to have that Gibson sound, that Gibson look and that Gibson feel. When the customer gets all of those at the initial purchase then we have done what we need to for Henry,” Ren says enthusiastically, using Henry’s name as shorthand for the corporation as a whole. So while he is without doubt a soldier marching to his own beat, he is keeping pace with the rest of the troops and very much moving to the same music, in the same direction, as the rest of his coworkers. He describes his co-workers like, “a bunch of star children in the olympics.”

How do you describe this symbiotic relationship between the Boseman plant and the whole of Gibson, between Ren and his crew? The best way is through history; had Louis Comfort Tiffany not had a large factory, we likely wouldn’t revere the name Tiffany as we do today. Had Stradivarius not lived to the ripe old age of 90 and had many sons and grandchildren building wonderful violins, chances are we wouldn’t have heard of him either. In short, an “arteest” will ultimately be dependent on a financially successful partnership to flourish and achieve the prominence in the marketplace they deserve. That’s not to say that Ren Ferguson would not be still making the fabulous guitars if he was working under his own name, but now they are museum-quality Gibsons.

| |

|

We may deduce that, at 62 years old, Ren’s clock is running, that there are a finite amount of Ferguson Gibsons to yet be had. By tenure alone, the Ren period at Gibson has already exceeded the Loar period. Fortunately, he remains dedicated as ever to his craft. While a touch of arthritis in his left hand has made some of his work more difficult, he continues to do most of his pearl cutting with a jewler’s saw by hand and without the aid of glasses (although he admits to needing a jeweler’s loupe for the engraving of pearl).

He’s also staying abreast of developments in luthiery and in building materials. Although he likes real abalone and mother-of-pearl for his inlays, he admits to having a fondness for abalam, a relatively new product that is essentially slivers of abalone layered in an epoxy-like resin and made into large sheets of material. However he doesn’t use abalam on the guitars that are in the Master Museum line or on any custom guitars that are made at Bozeman. “I can’t engrave abalam with any consistency. There are machines that can engrave it, but the texture is too irregular for me to do it by hand.” Ren doesn’t use a Dremel tool for inlay, but instead uses a Pencil Dye Grinder that is air driven and spins so fast that is has virtually no vibration. Ren has passed the guitar lifestyle down to his sons as well. His older son, Matthew, works for Gibson artist relations in California; his middle son, Tim, has shown a gift for doing inlay like his father, and is currently doing inlay for Gibson under Ren’s guidance. And although making guitars is largely an indoor activity, Ren’s soul longs for the skies, seas and mountains. Ren always wanted to be outside as a kid; he even made his own surfboards as a young man. He still considers himself an “outdoors man.” As a hobby, Ren raises pigeons and begrudges having to tote them water at “dark-thirty” in the morning, as he calls it.

When asked if he would like to retire, he admits he would like to drink a glass of orange juice off his front porch on the ocean and go out on his surfboard at morning’s first whisper, but he feels it may never be in the cards. So hopefully there will yet be a few more Master Museum guitars in the near future, and perhaps a few hundred more Gibson labels to be signed.

John Southern

Southern is a musician, songwriter, photographer, and guitar builder from Tulsa, Oklahoma. He is beginning a new TV Show called “Talkin’ Guitars.” He can be reached at johnsguitarshop@aol.com.