Professional guitarists in the ’80s and ’90s were as likely to recognize the name Bob Bradshaw as Eddie Van Halen. In that era of refrigerator-sized rack systems, awash with glittering LEDs, “Bradshaw Boards” reigned supreme. Attending a concert featuring Dokken, Aerosmith, Metallica, Megadeth, Journey, Motley Crüe, Def Leppard, Toto, Steve Vai or the aforementioned EVH meant seeing, or certainly hearing, the result of Bradshaw’s work as a gear systems designer.

Nor were his customers restricted to the hard rock/metal crowd. You were as likely to experience a Bradshaw rig at shows by Steve Miller, Lee Ritenour, Duran Duran, Steely Dan, or even Gloria Estefan and Madonna. Touring guitarists in all genres came to Bob to have their pedals, rack gear, and amps wired together in a reliable, roadworthy, system—a system that offered instant access to any sound required.

With his company Custom Audio Electronics, Bob Bradshaw is still constructing hand-built systems for the likes of Billie Joe Armstrong, Dweezil Zappa, and Trey Anastasio at his live/work space in the Los Angeles’ Brewery Artist Lofts, a converted Pabst Blue Ribbon plant. We spoke to him about the rise and fall of rack gear and the bad rap that buffers suffer.

Where did you grow up?

I was born and lived in Florida until I went

to electronics school in Atlanta, Georgia, in

the late ’70s. I didn’t have any electronics

knowledge, but I was the kid with the biggest

stereo—I just loved music.

Were you a guitar player?

No, I bought a guitar just so I could hold it

[laughs]. I bought a Tele Custom because I

loved Danny Kortchmar and he played one.

I bought an Acoustic 150 amplifier and

built a cabinet but I could barely play a lick.

I just wanted to be part of music somehow.

You say you built a cabinet. Were you

always handy in that way?

No, I bought a Dynaco Stereo 400 power amp

kit and it was too intimidating—I couldn’t do

it. I had a friend at work put it together.

After high school, I wanted to get into engineering but there weren’t many recording schools back then. I figured if I learned what was going on behind the knobs; that would give me a skill to help me get into audio engineering, so I went to DeVry Institute of Technology.

I did very well there. My math skills weren’t great, but luckily the pocket calculator came along around that time [laughs]. I graduated at the top of my class and got recruited to come to California to work for Hughes Aircraft. I figured the music industry was in California, so if I got out there maybe I would find something I could do.

I worked for Hughes for a year, and then saw an ad in a newspaper for Musical Service Center—a place that fixed instruments. I went in with no experience, but they hired me to be a bench technician. I got thrown into the fire, getting the crap shocked out of me working on Marshall amps. Fortunately some guys there helped me.

Was this the early ’80s?

It was around ’79 or ’80. It was all pedals in

those days—rackmounted pieces were just

starting to come along. I might occasionally

see an Eventide H910 Harmonizer, or an

early Roland rackmounted delay.

I hated seeing guys bending over to diddle with their pedalboards in performance. The pedals were different sizes and different shapes, some had lights some didn’t; I’m thinking, “You have to get that stuff off the floor. Why not have a separate bank of switches to control the pedals?”

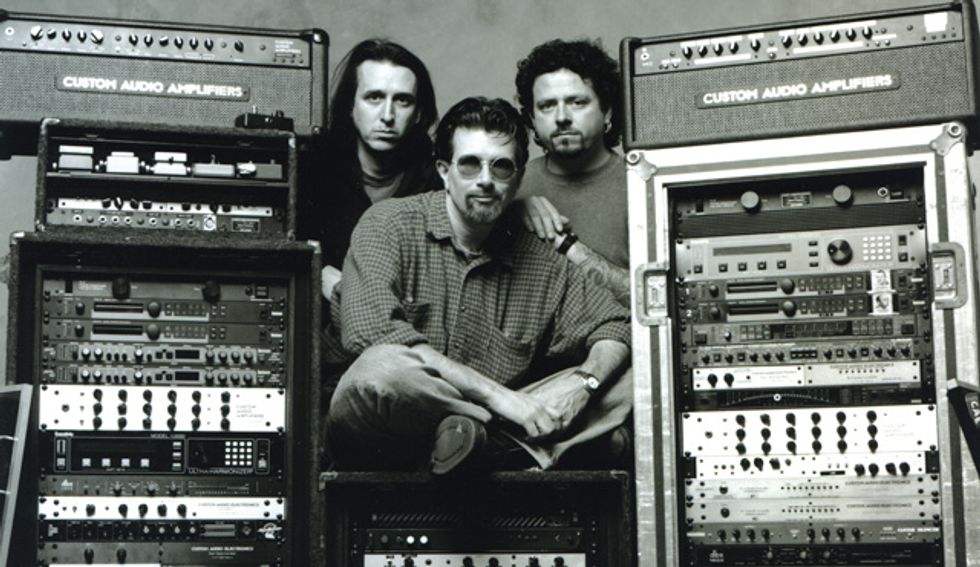

Custom Audio Electronics founder Bob Bradshaw

(center) with Michael Landau (left), Steve

Lukather (right), and the racks he set up for them

in the ‘90s.

My main inspiration was Craig Anderton and his technical articles in the back of Guitar Player magazine. In a series of articles, he mapped out an idea for an electronic switch, sparking in me the idea for a switching loop. I didn’t have any idea about Pete Cornish and what he had done in the ’70s—I just had this concept of a remote control switcher that could control all the pedals and rack stuff, so you are not running audio to and from the amp. Most of it would be back in a rack, neatly wired together, up off the ground, so you could adjust the pedals standing up. I wanted a patch bay arrangement with individual loops. I didn’t want to modify the effects; I just wanted them to work nicely together, so I developed various types of audio-routing circuits.

How did you get started selling this concept?

I built some custom pieces for a few players

around town. One of my favorites was

Buzzy Feiten. He had this crazy pedalboard,

and an Echoplex on a mic stand so he

could manipulate the delay time. He was

tap dancing on the pedals and bending over

to tweak them—it was distracting for the

player, as well as the people watching. I presented

to him the idea of building a floorboard

with labeled switches for each effect.

I didn’t know about professional racks or trays at the time so we mounted everything in a Technics home stereo rack. We cut slots into a piece of aluminum and mounted the pedals on the top: the Echoplex, a Boss EQ, and an MXR Dyna Comp. The rack stuff, like his Eventide H910 harmonizer, was mounted below. On that rig, the jacks for the loops were mounted on the top of the interface box; it didn’t occur to me to put them on the back. The front of the box had outputs for amplifiers, and a big, honkin’ multi-pin connector for the control pedal.

Buzzy is a tinkerer, always looking for better sound. I would learn new stuff and apply it to his rack. Through him I met Mike Landau, through Landau, Steve Lukather, through Lukather I met Eddie Van Halen, and through Eddie, Steve Vai. Then I met Andy Summers, Peter Frampton, and so many others— it was all through word of mouth.

How did you eventually connect with

John Suhr?

He came to me and wanted a switcher. He

is another one who is always looking for

the best way to do stuff. He was still working

at Rudy’s [Music Stop] in New York. I

persuaded him to come out here, gave him

a car and found him a place to live.

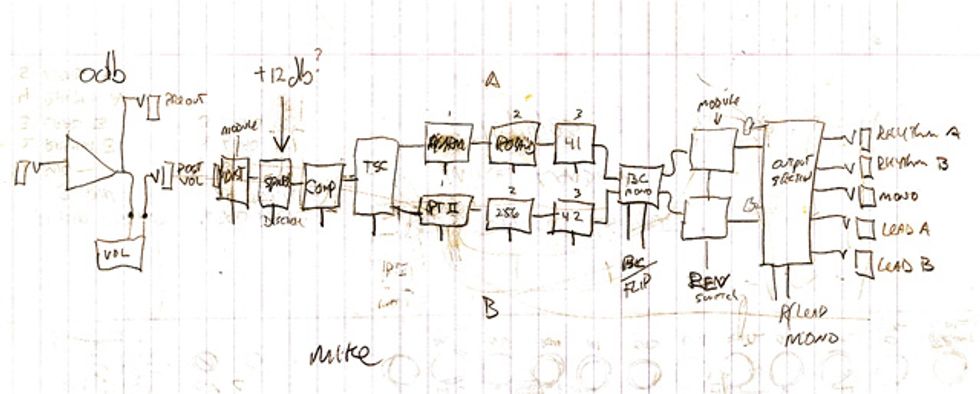

This 1982 sketch details the

first rig Bradshaw designed for Landau. Photo

by Glen LaFerman

Did he come out specifically to work

with you?

The story goes: I was working with Steve

Lukather, who wanted a switcher for his

multiple amp rig. We were using a Soldano

amp for the main solo sound, a Marshall for

crunch, and a Mesa/Boogie amp for clean.

It was really expensive to ship multiple amps

around, so I commissioned Mike Soldano to

build the first 3-channel preamp.

I gave Mike one of my switcher chassis and said, “I want totally independent channels with bass, middle, treble, gain and master for each channel. I want the first channel to be voiced like a Fender Twin, I want a Marshall crunch channel, and I want your SLO-100 preamp stage for the solo sound. And, I want to be able to remote control it from my switching system.”

He built it and that became the Soldano X88R preamp. It opened up a big new business for Soldano, who was charging $1,800 a pop for this preamp. But even though it was my concept, he was selling them to me for $1,700! And, there were things about the Soldano I didn’t like. There weren’t many guitar-voiced power amps at that time, so you would be shoving this preamp into a flat-sounding, solid-state amp or a sterile-sounding tube amp. I had to use an extra EQ stage to give them more life.

I started talking to John Suhr, who was doing Marshall mods by that time. John and I came up with some ideas for improving the three-stage preamp’s tone, and we added a tube-powered active EQ stage at the end of the chain that you could switch in and out of the circuit. John put the guitar thing away for a while and we started doing preamps and the OD-100 amplifier. I came up with the concepts and John designed the circuitry. We formed a company: Custom Audio Amplifier. When he left and went to Fender we dissolved the company.

Do you still manufacture the CAA amps?

John Suhr does that—I sold the rights

to him. I don’t make amps anymore.

I got into building hardware because

there wasn’t the hardware out there

to do what I wanted it to do. I never

wanted to be a big hardware manufacturer,

so I collaborate with other people.

I like building systems and working

with the end user.

So you are concentrating on

switching systems?

Absolutely, I have a new foot controller,

the RS-T, which is an evolution of

my old RS system.

Take us through the evolution.

When I started, the switches were what

you call direct access, or instant access;

there weren’t any presets. That’s why my

boards were so big: you had an individual

switch for each effect. The evolution

from there was being able to hit

one switch and make multiple things

happen. I came up with a scheme for

having programmable preset combinations

of these instant access switches.

There was no MIDI at the time, no

microprocessor involved, no code—it

was all static memory chips.

So you had one set of switches for

individual effects and a separate set

for presets?

Exactly, and it had switches to move up

and down banks. Rocktron came along

and wanted to come out with a system

based on mine. They added a character

display so you could name the presets. We

worked together through the ’80s and ’90s.

CAE custom switchers come in any size and configuration that will fit a player’s needs.

In the meantime I wanted a simpler system, so I developed the RS-10, with 10 direct access switches, four preset switches and two switches for bank up and bank down—16 total. You could expand that with an expander unit that had six more direct access and two more preset switches that would sit on the floor right next to the RS-10. It had just a three-digit display. The Rocktron thing ended, but I continued building RS-10 systems for hundreds of name players.

A few years ago I developed the RS-T. Based on the RS-10, it is MIDI, has a beautiful vacuum-fluorescent display for naming presets, inputs for four controller pedals, and is expandable from an eight-switch version to a 40-switch version. It is now assignable: You can decide what any one of those eight to 40 switches do.

In other words, you can decide

whether they are direct access to one

effect or a preset switch?

Or both—they are all direct access in

“direct mode.” In “preset mode” you

decide how many are preset switches.

Say you have 16 switches, you can set

it up so eight are direct access and eight

are presets, but in direct mode they are

all direct access. When you are in direct

mode the LEDs are red, in preset mode

they are blue. If they are programmed to

be momentary switches, they are yellow.

There are seven or eight colors, depending

on their function and 200 possible

presets. It is still evolving: We finally got

SysEx going so you can back up presets to

the computer, and we have USB ports on

them so we can develop editing software.

How have gear setups changed in

recent years?

It has gone more towards pedals. From

the beginning, for me, it has always

been about the interfacing of pedals

with rackmount pieces. It got very

rackmount heavy in the ’80s, now it has

come back around to mostly pedals these

days. Pedals are compact, and you can

spend a couple hundred bucks and have

a new sound.

The rack stuff got a bad rap over time, but that was just a format for the sounds. It is harder putting together systems with pedals— you have so many different voltages and connectors. Also, think about it: You are spending $300 for this pedal and then you are stomping on it. That is another reason I wanted to get the stuff up off of the floor.

Eddie Van Halen with his 5150-tour switching system—the first rig Bradshaw ever designed for him—in 1986.

How are you dealing with this trend

towards pedalboards?

That’s the thing I am most excited about

pursuing these days: a pedalboard-based

switching system. That’s why the RS-T

controller is long and thin: so it can fit on a

pedalboard. I don’t like pedalboard switchers

where the loops and controller is one unit,

where you are stomping on the audio router.

I prefer a controller that you step on, with your pedals sitting in between that and an audio loop router that you patch into on the perimeter of the board, or what I call the audience side. It is still a two-part system, it’s just that the audio router and pedals are no longer back at a rack.

Are you selling the pedalboard

controllers yet?

Oh yeah, there are dozens of them out

there. The controller is an off-the-shelf

piece, but the audio routers are custom

built. Everybody’s rig is different, that’s what

makes this still fun after 30-some years: One

guy’s system might be stereo, another mono;

one guy might need eight inputs, another

just four; one might want to use the effects

loop of an amp, and someone else might use

a preamp and a power amp.

My systems are based on a format of switchable functions. These functions might be a loop, or a switchable output— to send the signal to various amps. It might be a control function: maybe an isolated relay contact closer, for doing channel switching. Then there are subsets like A/B switches, A/B combiners, mixer circuits, and summing amps.

If you want something custom built, I am the guy who can do it. Sometimes it might take a while because it is labor intensive. I have an assistant or two, and an assembly house that puts together the RS-T units, but my hands are on everything before it goes out of here.

Do you just supply the system or do you

wire up the whole thing?

It is all built and wired by my assistant or

me. There is a science to laying all these

things out—it’s like a game of Tetris. You’ve

got all these pedals in all these different

sizes, and everybody wants it small, and

light, and that ain’t easy. That’s the biggest

trend, smaller and lighter.

How do you deal with things like fuzz

pedals that have to have the guitar coming

directly into the input?

They are in a loop but I don’t buffer

before them. I rarely have any active circuitry

in the first five to seven loops. I

only put a buffered circuit in the signal

path where it needs to be—where you

would hear a difference if it wasn’t there.

For example: if you are running multiple amplifiers, you have to transformer isolate them so you don’t get a common ground and a bunch of hum. A passive guitar signal won’t feed a transformer, so you have to add some active circuitry at the end of the chain Or, in the rackmounted systems, there might be three or four passive loops, but then I have to send the signal back to the floor—to a wah or volume pedal. At that point I would add a buffer but not before.

I am building a lot of two-board systems. The trend is to mount the controller on one board and the pedals on another board rather than a rack tray; those sliding rack trays don’t hold up. If you fly—and more people do these days— the racks get creamed by the monkeys loading them at the airport. So I mount everything on boards in a suitcase-type enclosure—suitcases come through the ramps better than a rack tumbling down.

With a two-board system, at your stage position you have a board with your controller and maybe a couple of pedals like a wah, or volume, and a tuner. The signal has to be sent to a second pedalboard offstage or back by the amps, where all the routing is taking place, so on the first board I put a little MC-401 boost/line driver I designed for Dunlop.

On a two-board system, the buffer is essential. Let’s say you have 10 feet of cable from your guitar to the first board, plus the loading from your wah and tuner, then 30 feet of cable connecting to your second board back by the amps. Now you have 40 feet of cable, and maybe some passive loops in the audio router. You need some sort of buffer or your tone is going to sound filtered. The buffer has a hardwire-bypass switch, so you can turn it off if you are switching on a fuzz that needs the signal to be completely passive. You will have some loading (or filtering) at that point, but you probably won’t notice, because this raunchy fuzz is on—it is all a compromise somewhere.

Do you have any advice for players who

can’t afford a custom system but want to

improve their rig?

The cleanest form of signal path you can

have is to put your stuff into some form

of looping system—as long as the looping

system is well designed, because not only

is it bypassing the pedal; it is bypassing the

cables connecting the pedal. And don’t get

me started on true-bypass pedals. If you

have 10 true-bypass pedals in your chain,

even with all of them off, you are going to

hear a difference.

Don’t be afraid of buffers. That term is so misconstrued. People say, “I don’t want a buffer in my signal path.” What does that mean? Chances are you already have one—a Boss Tuner is a buffer, even when it is off. A buffer is nothing more than an impedance converter. Theoretically it should have no coloration of its own, but driving the signal with it is going to color the signal, if only by restoring it to what it would be before being “colored” by all the cables and pedals in the path. If you were to plug a three-foot cord and nothing else between your guitar and amp, that would be the purest signal you could get. But who wants to stand three feet from their amp?

What other products, besides the buffer,

are you marketing with Dunlop?

I do some pedals and a power supply and

a wah wah with them. The thing is, you

come up with concepts, then you have to

build multiples of them—that is the part

that gets old for me. That’s why it is good

to partner with people like Rocktron and

Dunlop. Let them build the stuff—I am a

system designer.

Practical Pedaling

Bob Bradshaw's Advice

Pedals have come back from their initial popularity in the ’80s, says effects systems designer Bob Bradshaw. “They’re great because it’s a self-containing little thing,” he says. “There are tons of people out there making all kinds of different things so it’s wide open in terms of the choice you have in sounds.” When he first started his career in pedalboard engineering, there weren’t many rackmounted pieces—the ones he worked with were studio pieces like Eventide Harmonizers, for example. “I remember the first time I saw a rackmounted Roland delay that Buzzy Feiten had and I was like, ‘Wow! Look at that,’ because it was like a space echo.”

While rackmounted pedalboards are very common now with touring guitarists, Bradshaw’s innovation with two-board systems uses a controller mounted on one board and the pedals on another board rather than a rack tray, which Bradshaw says is easier on pedals and allows for for better upkeep and transport than rackmount trays.

Here he gives some general advice on what to consider when designing your own pedal setup, from streamlining your board to your specific needs as a player.

1 First things first:

How do you play?

When a player approaches

Bradshaw for

a custom-built product,

the first thing he asks

is, “What do you need?”

Rack or pedalboard?

That is the question.

Next he’ll ask you to

consider every effect

and element you want to

include, so that you can

consider order routings

of the effects. “Order is

subjective, “ Bradshaw

says, so it’s up to the

player to figure out what

order they are most comfortable

playing through.

2 Clean up

your signal.

Put your pedals into

some form of looping

system, Bradshaw

advises. This is optimal

“as long as the looping

system is well designed,

because not only is it

bypassing the pedal; it

is bypassing the cables

connecting the pedal.”

3 Follow your

instincts.

Bradshaw has just

about seen it all in his

decades of switching

system routing, and

through this he’s learned

that in the end, it’s all

about personal preference.

“Anything goes, it

doesn’t matter, as long

as it works for you.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)