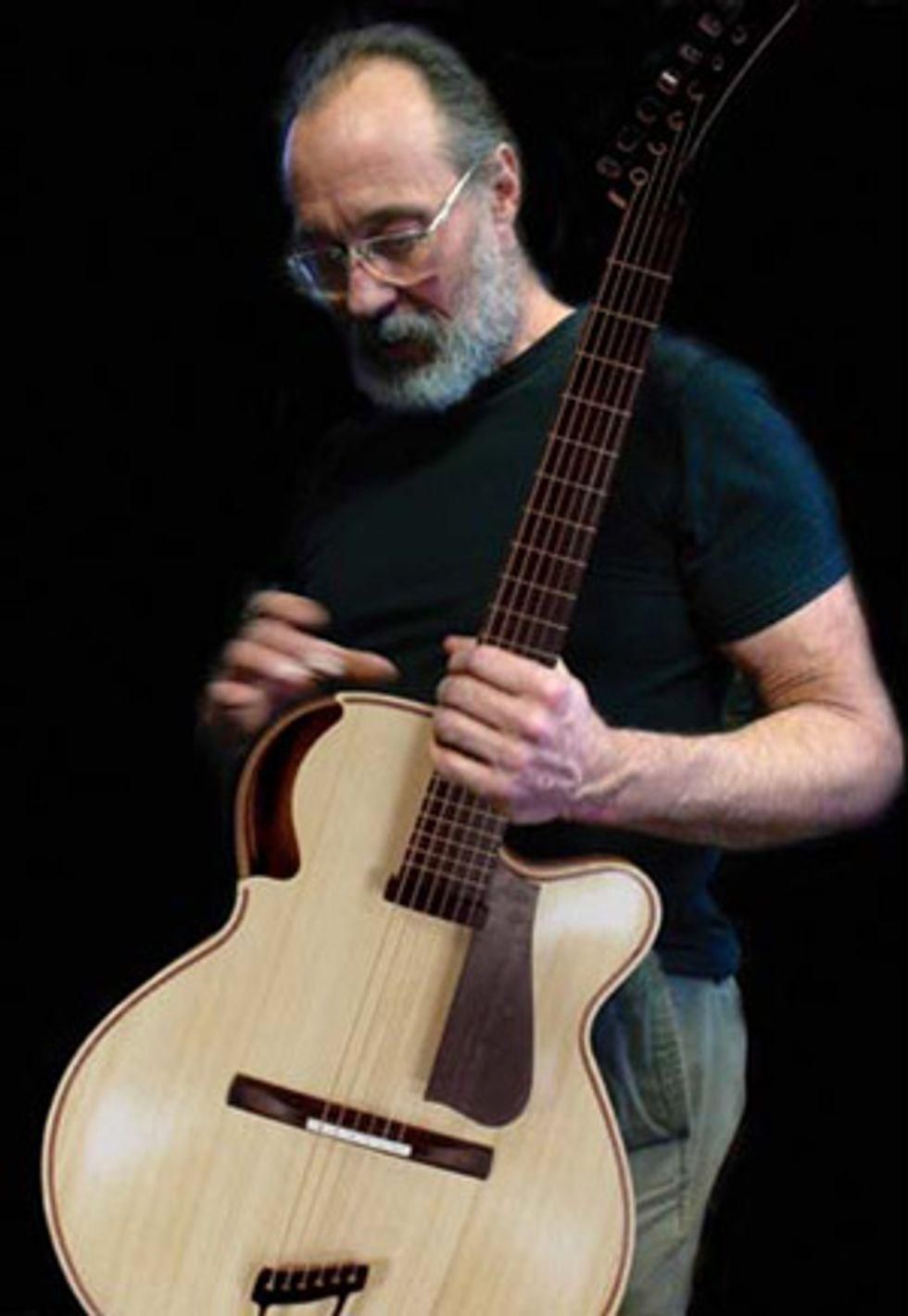

Though most players know Ken Parker because of the innovative guitar he and Larry Fishman designed and introduced under the Parker Guitars brand in 1993—the Fly—he has been obsessed with archtops for decades. Given the Fly’s striking ergonomics, composite-covered body, carbon-fiber fretboard, and proprietary, multifunction tremolo—all of which made it one of the most unique and successful new solidbody designs of the last 20 years—it should come as no surprise that Parker’s obsession is now advancing the art and science of archtop guitars. But that shouldn’t overshadow the fact that he does it all because he’s striving to inject the playing experience with real joy: “To me, if a guitar isn’t fun to play—if it doesn’t put a grin on your face and beckon you from the corner of the room—what is it for?”

To provide insight for this article, Parker sent a guitar for us to spend some time with and get the hands-on Parker archtop experience. The first touch is extraordinary. It’s featherlight and incredibly comfortable to hold. The neck is smooth, wide, easy to play, and devoid of anything that might create tension. When I played an Em chord, there was so much . . . everything—so much bass, so much liveliness, so much sustain. Everything we think the opposite of when we think archtop. And yet, it’s all archtop.

Though Ken Parker still uses the same headstock shape found on the Parker Fly, the simiarlities to his current archtop designs end there, and he no longer has a stake in Parker Guitars.

Clockwork

Parker trained as a toolmaker for a grandfather- clock making company before he started building guitars. “This beautiful guy kind of took me under his wing, because they didn’t have somebody to do all the tooling they needed—not the wooden parts, the metal parts. It was like going to grad school. I did four years worth of training in a year and a half.”

That training and facility for machining custom parts would play a vital role years later. Today, Parker handbuilds almost every piece of his archtops. “That is really a huge ingredient of who I am now—it was an incredible playground,” says Parker. “I was a sponge. It was just thrilling to me. I had dropped out of college, because I was studying philosophy and physics and I didn’t know what I was going to do with that. But I sure knew I liked to build things. I used my brain, my imagination, my body, my coordination, my balance, my eyes—all that stuff. It seemed so rich an endeavor—I just loved it.”

Parker also did serious repair work as a guitar tech in those early years. One of the first and most troubling things he learned on that job was the appalling state of fretwork on even guitars right off the shelf. “It’s better now than it was 30 years ago. I was doing refrets on brand-new, made-in-America guitars that were unplayable. I was offended. I felt that those companies weren’t taking musicians and their needs seriously, and it really bothered me.”

That eventually led to the now-legendary stainless-steel fretwork on the Parker Fly. “I had done thousands of fret jobs by the time I started that company. And one of the original design goals I told my partner, Larry Fishman, was “If I can’t build a guitar that doesn’t need fretwork, I don’t want to do it.”

Evolution of a Revolutionary

This Brownie model features a red

spruce top, curly mahogany (on

the back, sides, and neck), and a

European spruce neck core.

Parker got serious about playing jazz guitar

when he was 22, and he took group lessons

with a teacher named Dick Longale. One of

the most important things that happened in

those lessons was that they gave him his first

exposure to a good archtop—Longale’s Gibson

L12. “It was beautifully balanced, rich sounding,

complex . . . We were all trying to turn

the knobs on our guitars to try and sound like

Dick, but we couldn’t. So I was intrigued.”

The other significant development was

Parker’s realization that he wasn’t going

to be a player. “No matter how much I

practiced, I was still struggling after two or

three hours a night. So I said, ‘Well, maybe

I’ll just try and make one of these things.’

That was in 1974.”

Parker’s Brief Archtop Primer

Being in the New York area was a boon for

Parker and his aspiration, because it offered

him many opportunities to get his hands on

archtops. He quickly became an avid student.

“The archtop guitar is one of the very few

instruments on our planet that was not the

product of an intensive period of competition

by competent builders. You can count

on one hand the number of people who

built archtop guitars by hand before 1975.

And that’s just weird. The pianoforte came

from these little carry-around-in-a-suitcase

instruments, and it took 300 years to develop.

The violin went through a huge period

of development—we’re talking

centuries. And even the classical

guitar is still evolving. But the archtop

was basically stillborn.”

By that, Parker means that many of the earliest archtops left a lot to be desired. “They weighed a ton—they were made like packing crates. Then all these marketing geniuses got together with all these German craftsmen in Kalamazoo, and they made some pretty cool stuff—mandolins, flattop guitars, archtop guitars in the model of [Orville] Gibson . . . but they made them better. And then, in 1922 they hired this genius [named] Lloyd Loar. He was only at the company for about 26 months, and in that time he invented and perfected the F5 mandolin, the Mastertone banjo, and the L5 guitar. He is my hero.”

The L5 did get some improvements after Loar left Gibson in 1924. “The examples that are most highly prized by people who listen were made in ‘27, ‘28, and ‘29,” Parker continues. “You could make an argument that no one seriously built an acoustic archtop since 1929 except for two people, D’Angelico and Stromberg, because in 1938 Charlie Christian came along. He was like an evangelist— ‘Get a pickup guys!’ And everybody did!”

After that, archtops were built heavier to avoid feedback—but that made them less responsive and rich sounding. “They were really electric guitars with air inside,” Parker says. “I don’t mean to say there weren’t some brilliant guitars made by these guys—and hats off, because when they came out great, they were great. But a lot of them were pretty clunky, quiet instruments.”

Achieving “Knighthood”

Mrs. Natural has a red spruce top,

rift-cut Big Leaf maple (on

the back, sides, and neck), a bronze

tailpiece, and snakewood veneers on

the fretboard, headstock, strap

buttons, and bridge

In 1976, a young Parker tried to get an

apprenticeship in Jimmy D’Aquisto’s shop.

He took the first archtop he’d made to

show D’Aquisto that he was serious. He was

turned down, but D’Aquisto clearly saw

something magical in the

instrument Parker had made.

“He said, ‘This is the best first

guitar I ever saw,’ and on my way out

the door he said, ‘You’re crazy if you stop

building guitars.’ I walked out of there

going, ‘I guess I’m a guitar maker.’ He

shop in 1976.”

Thus began the obsession. “This is what I think about before I go to bed, what I think about in the shower. I’ve worked on thousands and thousands of guitars. I’ve seen all the good stuff and all the funny stuff, and I’m trying to make my contribution to the field and make a better guitar.”

One of Parker’s innovations is his bridge. “The majority of the response from any acoustic guitar comes from the top—not only the two pieces of wood that normally make the top, but also the braces and the bridge. For reasons I don’t understand, most people don’t think of the bridge as a transverse brace. But that is exactly what it is. On the classical and flattop, it’s bonded to the top, and on an archtop it’s forced down against the top. It’s well known that the material in the bridge, the size and weight of the bridge, and the configuration of the bridge impact the sound of the instrument. And not only is the bridge a transverse brace, it’s also a transducer that changes vibrational energy into sound energy by delivering the vibrations to the top. It’s a key part of the signal path from the strings to the top. So why are we taking this holy piece of material, cutting it in half, and putting a couple of hokey pieces of 6-32 brass rods and adjusters in there? It never made any sense to me.”

Parker makes most of his bridges out of ebony. They start out at 120 grams, but he hollows them until to 21–24 grams. “It would blow off a bench in a little breeze. It is no thicker than an eighth of an inch, and many places are much thinner than that. That’s partly what contributes to the low end of the dynamic range. You haven’t got string and it’s very happy to light up and make a sound.”

Since these miniscule bridges cannot be adjusted to change the action, Parker decided to make action height adjustable by the player, on the fly. The neck literally floats over the guitar’s top—the only thing touching the body, aside from the bridge and tailpiece, is a carbon-fiber neck pin that extends into a thin-walled receptacle of aluminum tubing bonded inside the neck block. On the back of the guitar is a small, round grommet through which a hex wrench can be used to move the neck up for ridiculously low action or down to, say, play slide.

“With [that design], I got all these other great features: incredible access to the second octave because there is no heel, de-mountability for repair or travel, lots of room for a neck-end-mounted electromagnetic pickup, and the ability to fit another neck to the guitar for a different scale, a different number of strings, or whatever.”

It took Parker nearly a year to perfect his neck system. “I start with a neck core out of my favorite stuff—beautiful-sounding, perfectly quartersawn Douglas fir or spruce. This one-piece core is only visible on the side of the headstock, but it goes all the way to the end of the neck. The back of the neck has a hardwood veneer that matches the sides. Between the veneer and the neck core there’s quite a bit of carbon fiber set in an aerospace resin that needs two hours at 275 degrees Fahrenheit to cure. Room-temperature resins just aren’t rigid enough to do that job. It’s kind of challenging—you have to make a metal mold, you have to get the resin pretty hot, and it’s kind of tough to control all those things and have them all come out looking gorgeous at the end. I can’t tell you how happy I am with the result. It works just beautifully.”

Hold Your Head(stock) High

Parker makes every single component of his archtops except the tuners and the strings. For the tuners’ home—the headstock—Parker machines a strop of aluminum that resembles the Parker Fly’s headstock, has it anodized, and then, unlike most archtops, positions the tuning pegs in a row. But he doesn’t use this arrangement for aesthetic or branding reasons. He says there are two things that can change the dynamic tension of a string: the angle over the bridge and the nut, and the after length—the distance between the bridge and the termination at the tailpiece, and between the nut and the tuning peg.

The Fig flaunts its incredibly figured

Big Leaf maple. Note

the hexwrench

port for adjusting neck

height and action.

“That’s why, in one man’s opinion, a three-and-three headstock is just plain-old physically wrong.” Parker reasons that it doesn’t make sense for the tension of the high-E and the B strings to be the same as the low-E and A strings. “I think it makes the strings feel wrong. You have to get everything right in order to create an extraordinary experience for the player, and I really try to get this balancing-the-string-tension thing right. It’s not my idea—this is a European idea from hundreds of years ago—but the only way to do it is to put all the strings in one line, so the top string is more supple than it would be otherwise, and there’s a nice, even progression in tension.”

He says that arrangement facilitates greater customization, too. “For example, if you primarily play rhythm guitar, and you don’t care so much about bending strings, I’m going to make you a left-handed headstock for your guitar so you can put huge strings on the bottom and they won’t feel too tight—and they’ll drive the pickup crazy.”

Parker says his headstock angle makes the instrument feel more playable, too. “Gibson’s is 14 degrees. Mine’s four and a quarter. It’s as low as you can get it and not [have the strings] come out of the nut slots and start behaving badly. And I know, because I’ve explored it!”

This view of the Fig reveals its

Douglas fir neck core, as well as the

Waverly

gears set into Parker’s custom-

made anodized aluminum strip.

Wooden Boxes

Arguably, one of the sexiest things about the Parker archtop is the way he’s cut the soundhole into the shoulder instead of putting f-holes on either side of the bridge—although he’s certainly not the first luthier to shift the soundhole or change its shape. “Now, I realize I said Lloyd Loar is my hero, and it was his idea to [put f-holes on the top] in the first place. Having said that, it still doesn’t look like the right place to me, because that’s valuable real estate—that’s part of my ‘speaker cone.’ I put the soundhole in what I call the least-worst place. It’s as far away from the bridge as I can get it, and it’s as close to the player as I can get it. It delivers this immediate sound that makes people feel so confident. A lot of low end is available to the player.

“I have been able to create a guitar that has very, very even output, note to note and string to string, and very, very good separation within chords. You can play a chord with consonant or dissonant notes, and you can hear all the notes. It doesn’t turn into a bunch of stirred-up warm ice cream. Note separation, clarity, and evenness— those are big targets for me.”

Parker’s optional pickup was designed by Scottish archtop builder Mike Vanden, who collaborated with Larry Fishman to create the Fishman Rare Earth soundhole pickup. For his archtops, Parker takes the pickup apart and puts the coils in an ebony-veneered box that rests unobtrusively at the end of the fretboard. He hides the batteries, 1/8" jack, and controls under the pickguard. it serves these guitars beautifully through a variety of amps. With an L.R. Baggs Core 1, it sounded stunningly clear, brilliant, and full. Plugged into a Vox AC15, it produced a wildly satisfying growl while retaining the richness that defines the guitar.

As for the main “box” on a Parker archtop, it’s gloriously empty. Look inside the soundhole, and you see nothing but hand-bent kerfing and an X-braced top with two delicate pieces of spruce. “When I brace a guitar, I put in two braces,” Parker explains. “They’re off-center, for nefarious reasons of my own, and they don’t touch. I glue one brace on first and tune it, and then I glue on another brace that hops over the first brace. They taper out to little tiny whiskers at the glue line. If you don’t do that, you won’t get a big, supple low end—period. The braces are there not to keep the top from collapsing, they’re there to unify the behavior of the top so that it doesn’t get out of phase with itself and create dead spots and wolf notes. If there’s a trick, if there’s a secret, it’s getting those five pieces of wood—the two sides of the top, two braces, and one bridge—to work together to be an efficient structure so that you can get some real dynamic range out of the guitar.”

The soundport offers a look at

Mrs. Natural’s immaculate interior.

As for the wonderfully natural-looking and satin-soft finish on his guitars, Parker says it’s clean, easy to apply, and environmentally safe. He first applies an epoxy sealer, wipes it off, and then applies an old-fashioned oil varnish that’s designed for gun stocks. “If you put on a few coats, it looks kind of satiny and dry, and if you put on twenty coats it looks glossy and wet. And it’s repairable in a way that other finishes simply aren’t. If you get a dent in the top but you haven’t busted any fibers, you can pretty much take the dent out with an iron and a wet cloth.”

The Goose Bump Dance

When all is said and done, it’s no exaggeration to say that Parker doesn’t just walk the line between artist and scientist, he dances along it. His archtops are handmade, utterly unique masterpieces—from the strap button to the tuning-gear strop. He sums up his motivation and mission statement by saying, “I want to build instruments that give people goose bumps—and I don’t really care that it takes me a long time. Because when people play my archtops they say, ‘This makes my Martin sound like there’s a blanket over it.’ And that’s what I want to hear!”