|

Superficially, a Stick looks like a wider and longer version of an electric guitar’s fretboard and is home to eight, ten or twelve strings. Unlike the guitar, the Stick is played by tapping or fretting the strings rather than plucking them – both hands sound notes by striking the strings against the fingerboard just behind the appropriate frets. If you were inclined to play the Chapman Stick like a guitar, you would find insufficient string space for standard techniques like plucking. Additionally, because the strings lie so close to the fretboard, normal picking techniques – if possible – would be disproportionately loud.

Superficially, a Stick looks like a wider and longer version of an electric guitar’s fretboard and is home to eight, ten or twelve strings. Unlike the guitar, the Stick is played by tapping or fretting the strings rather than plucking them – both hands sound notes by striking the strings against the fingerboard just behind the appropriate frets. If you were inclined to play the Chapman Stick like a guitar, you would find insufficient string space for standard techniques like plucking. Additionally, because the strings lie so close to the fretboard, normal picking techniques – if possible – would be disproportionately loud. Instead, the intended playing position is with the left hand on the bass side and the right hand controlling the melody, similar to a piano or keyboard. However, either hand can play either side or both hands can play the same side. The instrument’s distinctive arrangement lends itself to playing multiple lines at once, and many Stick players have mastered performing bass lines, chords and melodies simultaneously to amazing effect.

The first production model of the Stick was shipped in 1974. The original sticks were handmade by Emmett himself and featured serial numbers between 0 and 2000. However, it is nearly impossible to tell how many were actually made. After the first 2000 the numbers started again at 0, making for duplicated numbers. To further complicate things, when a piece of wood wasn’t good enough, it was discarded with the serial number still on it, generating many “missing” serial numbers. Sticks are now cut electronically and serial numbers have been continuous for nearly a decade, currently numbering just over 5000.

Over the years, Emmett Chapman has experimented with a variety of materials for his unique instruments to attain the same quality with faster manufacturing and lower costs. The first models were made from “super hardwoods” – mostly ironwood – but Sticks made from ebony and other exotic woods emerged in the early eighties. The early nineties saw the introduction of injection-molded polycarbonate resin models, and today Sticks are made from a litany of materials, including various hardwoods, such as padauk, Indian rosewood, tarara, maple and mahogany; organic materials like bamboo, which is easily dyed for a wide choice of colors; and graphite epoxies and other high-tech composites.

The Chapman Stick finds itself in a constant state of evolution, both in the components of the Stick itself and the accessories. Recent developments include linear fret markers to help the player feel the frets and stainless steel Fret Rails, which impart a cleaner, faster attack. Stick players are also benefiting from improved pickups and amps, such as the GK3A MIDI pickup; the new StepAbout stompbox preamp, produced by BassLab; and the StickAmp, a dedicated amp with onboard mixer.

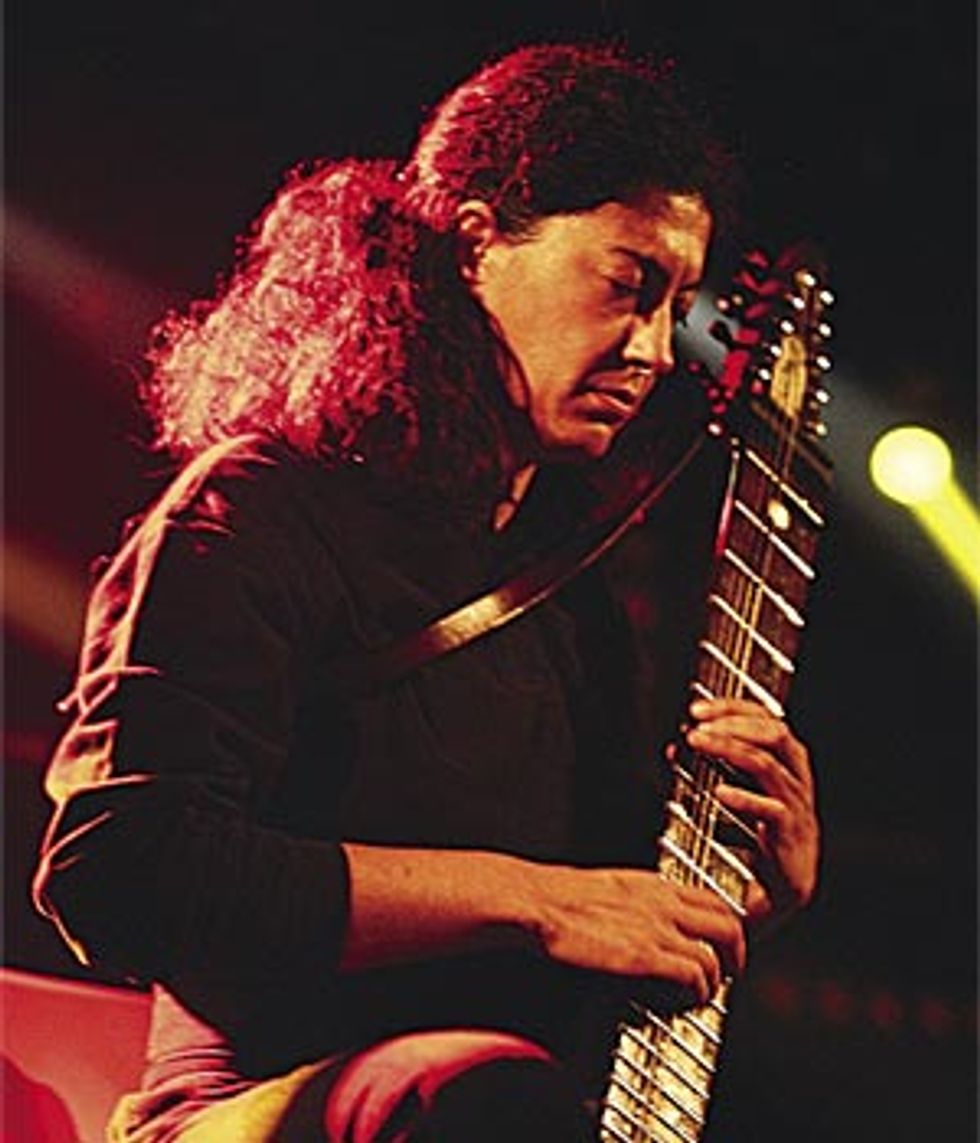

This uniquely-conceived contraption has always attracted guitarists, whether through genuine interest or out of sheer curiosity. We had the chance to talk to one of the best “stickistas” in the world, Italian player Virginia “Virna” Splendore.

Virna began playing the Chapman Stick more than two decades ago – only ten years after the Stick’s introduction to the music scene. She spent years playing the instrument as her passion and hobby while working for an Italian TV station. During this time, she became a premier Stick player in Italy and throughout the world, doing workshops and demonstrations in addition to performing and recording with her band, SplendoRe. In 2006 she dedicated herself full-time to the instrument and has since been actively touring and recording with multiple bands, as well as playing a significant role in developing products on the forefront of Stick technology.

When did you begin playing music? Did your musical career begin with other instruments before you found the Chapman Stick?

When did you begin playing music? Did your musical career begin with other instruments before you found the Chapman Stick? Well, when I was very young – like eight years old – I was a “lost wanderer” in the instrument world, looking for one that fit my approach to music. I took classical guitar, piano lessons and even clarinet lessons for a year. I also took lyrical singing, where I was a light soprano with a four octave range. Each of these instruments gave me something, but my real problem was studying – I don’t learn by reading an exercise and then playing it. I have a strong memory and musical ear, so I’m guided more by instinct than rules. If I get trapped into studying rules, I become like a tabula rasa, which means getting stuck on something. So, from age eight to 16, I understood that I wanted to play music but not in the way that I was being taught.

The one instrument that I really wanted to play was the bass. My mother said it was too masculine and encouraged me to pursue more feminine instruments, but when I was 19 I bought my first bass. When I discovered the Chapman Stick, I had to sell all of my other instruments to buy it – my clarinet, classical guitar and bass. Eight years later, I got another fretless bass – my first love – and realized that the techniques I had learned as a Stick player helped me learn more on bass.

What was your first instrument then?

My first instrument was a cheap classical guitar; I learned to play on that and sold it to buy my first Stick, which was a ten-string ironwood model with a passive pickup (now called the Stickup). It was the only model available at the time and I still own it; I rent it to those who’d like to try the instrument but have no idea where to find one.

How exactly did you come around to the Chapman Stick?

I met the Stick for the first time in September 1985 at the Milan SIM Trade Show. A friend of mine and I knew about the instrument from an Italian music magazine; when we saw that it would be exhibited at Italy’s biggest music trade show, we went to go see it live. My favorite Stick player at the time, and still my favorite, Jim Lampi, who has since become a great friend, was playing demos at Davoli’s booth, which was the distributor. His playing was amazing; the touch and the style were highly technical, but not intrusive. I felt he was playing from his emotions and I found myself with tears in my eyes! I said to myself, “That’s my instrument.” At the end of the show, I contacted the distributor and bought the Stick right there!

At the time there were really only a few Stick players in Italy: me, my friend who came with me and the late bass player, Stefano Cerri. So my friend and I started to learn together with a couple of Jim Lampi’s lessons on cassette tape, although I mostly just played it with the “Free Hands” manual from Emmett Champman. The next year, my friend and I went back to the trade show and did the demos at Davoli’s booth – it was my first trade show demonstration ever!

Did you set out to be a professional musician?

No, I actually started veterinary school but I never finished. Studying is not my cup of tea and I was stuck with too many books! I had gone to school in Milan, so I left for Rome where I worked with horses for very little money. At one point I had to decide to either become an instructor or leave the horses, and I decided to leave. I took some courses in camera operation and audio/video communications, another love of mine, and entered the real, working world with the national TV channel, RAI. I felt like Mowgli brought into the big city, bending to the "civilizations." I worked as a broadcast assistant for eleven years, all the while playing music in bands as a hobby and growing as a Stick player.

The TV work was month to month with no permanent position and I would sometimes go six months without a job or money. Finally in 2000 I decided to sue RAI for a permanent position and the suit took five years for a final decision. During this time I became the exclusive distributor of the Stick for Italy; I did seminars and taught the Stick, while producing music with SplendoRe and working on compositions and recordings on solo Stick, fretless bass and voice. I won the suit and got a cash settlement rather than the permanent position I had originally asked for, and decided to become a full-time musician. I don''t earn much and I struggle to find gigs, but I like what I do and the dimension of life is more human.

You''ve released a couple CDs under the band name SplendoRe. Tell us about that.

SplendoRe is the name of whatever project I start. The original duo was in 1994 with Roberto Fiorucci, a student of mine. We played together under the name SplendoRe, and made our first CD, Guilty, together. He quit playing for a couple of years for personal reasons in 2000, and the SplendoRe band formed with Raffaele Magrone on clarinet and Andrea Moneta on the drums and MIDI Stick. We recorded the CD, Different Things, with Roberto guesting on some songs. In 2004, Roberto came back to play and we either play as the SplendoRe duo or the SplendoRe band, depending on what is requested.

I recently formed the band Red Magma with Irene Orleansky, a Stick player and singer from Isreal, and Rodney Homes, an American drummer who has worked with Santana, Joe Zawinul and Randy Brecker.

Who have been your most important musical influences?

Who have been your most important musical influences? Well, I can say that a lot of people tell me they hear some Genesis influences in my music; others say Pat Metheny and some people say they can hear some Windham Hill [Records] influences. I''ve been listening to Seconds Out for ages, but never had any other Genesis records other than that. I''ve grown up with Pat Metheny, Lyle Mays and Michael Manring, and when I was very young, I used to listen for hours and hours to Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Dvorak, Mussorgsky, Ravel and Tchaikovsky. Then Elvis Presley came and I bought all of his LPs, and after that it was the Beatles, Yes, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Pink Floyd and the Police. I wore out the holes on those LPs!

Do you currently have any endorsements running?

I am an endorser for an Italian audio system manufacturer, SR Technology. They are great engineers who make really good amps. Around 15 years ago I stopped using amps for the Stick. I used to have a Carlsbro Stingray - a huge, 150-watt amp - a Fender, an Ampeg Gemini II tube amp and a Roland Jazz Chorus 55, which was the last amp I owned. But the Stick is a stereo instrument that needs to be amplified with more expensive amps and 600-watt speakers, which are too expensive and too big for me to transport. For years I''ve been playing live by going from my effect (at the time a ZOOM 9000) to a passive mixer and then directly into the PA system. I was still using the Roland at home.

When I heard SR Technology''s Jam 120, my ears were brought back to life! I said, "This is it, I want this amp." So after ten years without amps, I went back to them. The Stick has a large range, so the lows, mids and highs all need to be well-amplified and have a good response when playing bass and melody at the same time. It''s not easy with a bass or guitar amp unless you split the two sides to two separate amps. The sound on the Jam 120 was perfect - all of the frequencies were reproduced clearly and uncolored. It just sounded like the Stick. So I contacted SR Technology and became a beta tester of their prototypes, and I demo for them now at Musikmesse and the DISMA Music Trade Show in Italy.

I actually came up with an idea for a dedicated StickAmp, inspired by the Jam 120, and later the Jam 150 and Jam 150 Plus. These are combo amps with an onboard mixer that are very compact, with a powerful, punchy, clean, warm sound. I presented the Jam 150 to Emmett Champan, who liked it, and then Greg Howard, the great Stick player from Virginia. He tested the amp and suggested some changes. After two years, I tested the last prototype of the StickAmp. Emmett gave his approval and it is now with Greg for testing. Hopefully it will be in production by the middle of 2008.

What gear do you typically use?

Well, we''ve talked about amps. When it comes to effects, I hate big racks. I am well-known in Chapman Stick circles for my "Virna Sound," and it comes from a simple, small Korg Pandora PX3, designed for guitar. In the beginning I used to have a flanger, an overdrive, a reverb, a loop delay, and all of those little pedals from companies like Boss. When I got the Roland Jazz Chorus, I had all of my effects in the amp so I stopped using the pedals. I later upgraded to a Zoom 9000, which I used for ages. I use the Stick as a whole instrument more than splitting the sides, so a mono input with stereo output was perfect.

In 2000, I met [British pop musician] Nick Beggs at a seminar and he showed me the little blue box from Korg. I''ve tried the PX4 for bass and guitar, but the PX3 for guitar is the one that gave me my sound for five years. Now I''ve switched to a Boss GT-6B multi-effect pedal so I can change the sound whenever I need to during a song. I am also getting used to DigiTech''s JamMan loop station, which is helpful sometimes for solo playing. In the past year, I''ve introduced vocals to my performance, so I use a Proel wireless system.

How many instruments and amps do you have?

I have two old ironwood ten-string Sticks, a "middle-age" oak half-fretless Stick (only fretless on the bass side) with a Stickup, and my main Stick, a 34" laquered rosewood model with an active EMG pickup. I also have one of five prototypes of the XBL [Extended BassLab], which is a resin Stick produced by a German bass luthier named Heiko Hoepfinger. He''s a real genius who makes his instruments like a monocoque, hollow inside with any color you can imagine and unique designs. He received a license from Emmett to make the Stick with this material, which will hopefully be in production soon. I''ve had one of the prototypes since 2004; it sounds great and is very comfortable to play.

Last year I bought a used rosewood Grand Stick 7+5, which has seven melody strings and five bass strings. I''ve always wanted to try one of these models because the twelve strings have all the range of a ten string, plus the extra two low strings on the melody side. I composed a song on this Grand that should be on an upcoming CD I am recording with Red Magma.

I also have a black Yamaha BB350 fretless bass that I''ve had for ages and it still sounds great. I have a custom fretless bass that an Italian luthier named Makassar built for me. I liked his style and needed a fretless bass with a neck fit for my hands that was tuned for groovy riffs, so I asked for a bolt-on neck and four strings tuned BEAD, with a 34 1/2" scale and no high G for melodies. The Yamaha has the classic EADG tuning with a rosewood fretboard, alder body and maple neck, so the two sound very different. I like to call the Makassar bass "Arlequine," as it has so many different woods; spalted maple for the top, Italian alder for the body, a dark green Italian wood for the fretboard and maple and padauk for the neck. It''s a real beauty and the sound comes out deep and thick, depending on what pickup you use. I am also waiting on a fretted bass ordered from Makassar. It will be in standard tuning with an ebony top, mahogany body, maple thru-body neck and reddish cocobolo for the fretboard.

I also have a guitar that''s similar to a Telecaster, from the same luthier, which he calls the Telemaco model. It''s similar in shape to the Telecaster but has a totally non-electric sound - I must confess, I don''t love electric guitars. It sounds warm and the maple neck fits perfectly in my hand. I bought some instruments because I missed the ones I played before I started the Stick - this guitar was the last of those. Now I use them all; on my second CD, Different Things, I played one track using only this guitar.

Finally, I have a beautiful acoustic guitar handmade by Jacaranda, a luthier from Milan. The wood is traditional wood for a classical guitar, and it has RMC piezo pickups for each string. The guitar was designed for the guitar player Gabor Lesko. It has a wonderful rose with the Buddhist lotus design, as requested by Lesko, who is a Buddhist. The rose is positioned on the side of the top shoulder of the instrument, rather than in the center of the top. I got this Lotus guitar in time to use it on my last duet tour with Irene Orleansky; we toured Italy and Switzerland last November, playing all of our instruments and singing. The Lotus guitar was a pearl of sound during the performances.

Do you consider yourself a collector?

I wouldn''t define myself as a collector; I use most of my instruments live and in recordings. I do have love at first sight for certain instruments that I have only recently been able to afford, so they''re like a gift to myself. One is a violin that''s not really worth anything - I just bought it to study it. The other is a 34-string Celtic harp made of European and American cherry by a luthier friend of mine. He came to visit me and showed me his progress - I liked it so much I bought it. I try to play it a little bit and I would like to take lessons, but I just haven''t had the time. So those two instruments are mostly just for display.

How do you like your instruments set up?

How do you like your instruments set up? The Sticks need to have really low action by default to enable tapping. Three of them are in standard tuning - E A D G C F# B E A D - with light gauge strings. I don''t feel comfortable with medium or heavy gauges. My main laquered Stick has an active EMG pickup called the ACTV-2, while the Grand Stick is equipped with a standard pickup. After years of active sound, I needed to go back to a passive pickup for the typical stick sound - it sounds amazing on the lower strings. For the XBL, I am going to try tuning the melody side lower than the standard tuning and try different gauges. For the fretless Stick, I use a fourth tuning on the bass side, while the melody side is standard. Fortunately these tunings manage to stay in the range of a light gauge. Dedicated Stick strings sets are made by D''Addario and distributed by Emmett, and can be arranged in several kinds of tunings.

For the Yamaha bass I use a roundwound 40-95 R. Cocco strings with very low action, but for the Arlequine fretless I use an Elixir set with a big 130 as the B. I may bring the Arlequine back to standard tuning and have Makassar make a new five-string fretless bass, so I will have a low B and high G on one instrument. My fretted bass has 45-105 gauge R. Cocco strings and custom pickups from Mama. The Telemaco has low action as well as thin strings. I don''t tap or hammer on these instruments - I prefer picking on bass and guitar.

Can you share a moment from your career that has stuck with you?

I''ll always remember some magical moments that can only happen during rehearsal. Once I was rehearsing with a fellow Stick player, Roberto Fiorucci, and our drummer, and we just started to play some chords with a volume pedal. One by one we magically started to follow each other into a perfect interplay that seemed eternal. I have a recording of the session that I keep. It was all improvised, but I''ve tried to record it again doing all the parts myself. I played both Stick parts, but I got stuck on the drums - I''ll have to find another drummer who can play it.

What about your downtime - do you also play music at home?

It depends. I have my music room, and it happens that sometimes I pass most of the day inside there, just playing and recording. Sometimes I don''t even touch an instrument unless I have to rehearse for a gig. I have a very strange relation with music. I listen to music depending on my mood and it has to be in certain intimate moments. It''s difficult to explain!

Stick Stuff

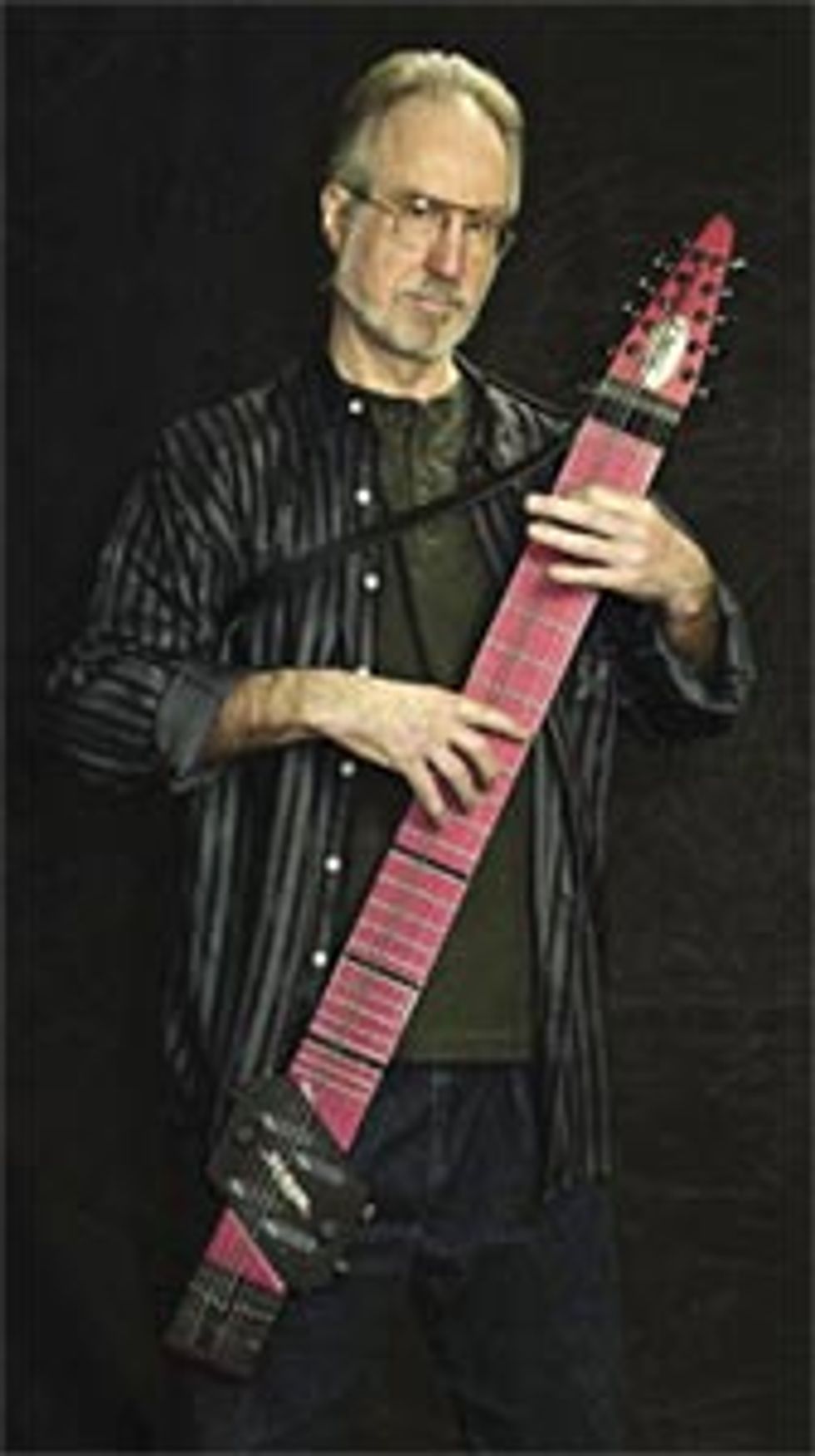

Unfortunately, the number of Chapman Sticks out in the wild is small, so the ability to check one out in person remains a long shot. In this case, YouTube is your friend, showcasing some amazing Stick work by such luminaries as Nick Beggs - former Kajagoogoo bassist and current Bass Guitar Magazine scribe - and Emmett Chapman himself.

As far as recorded works, Greg Howard contributed Stick to the Dave Matthews Band''s Before These Crowded Streets album, and Tony Levin spews Stick all over King Crimson''s early eighties output. Any of the three albums from this time period - Discipline, Beat and Three of a Perfect Pair - deliver amazing Stick rhythms and textures, as well as display the incredible interplay between Levin''s Stick machinations and Belew and Fripp''s idiosyncratic guitar work.

If none of the above sounds appealing, check out the Blue Man Group the next time they''re in town - they''ve been known to rely on the Stick for a portion of their act.

Virna’s Gearbox

|

Virna Spendore

myspace.com/virnasplendore

stickist.com/virna