Alf Binnie’s archtop features a rich antique burst finish and a pearloid pickguard.

April 26, 1942, was a day of anticipation and relief for the Allied prisoners of war at Stalag IX-C in the central German town of Bad Sulza. It was relatively early in World War II, and the POWs had no reason to believe they would be released anytime soon. They lived a squalid, crowded existence and were emaciated from meager rations of cabbage soup and hard bread.

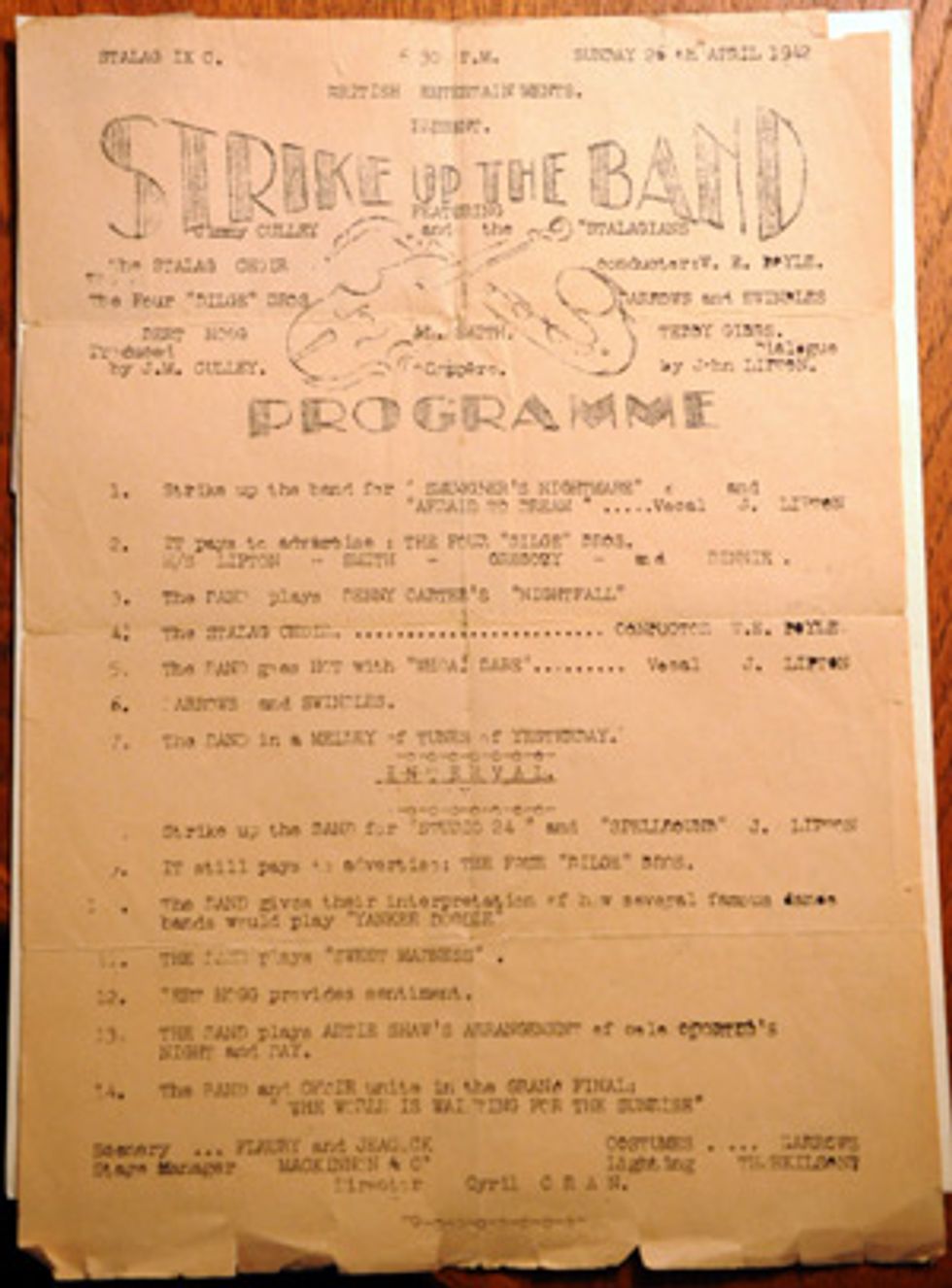

But that Sunday marked a rare occasion for smiles: The inmates—who came from many nations, including Poland, Belgium, and France—had been given permission to put on a concert, complete with a stage, sets, costumes, and lights. Dubbed Strike up the Band, the evening gala featured sets by a rag-tag orchestra by the name of Jimmy Culley and the Stalagians, and a smaller jazz quartet billed as the Four Bilge Brothers.

Though life in the Stalag IX-C Nazi POW camp was dismal, with plenty of hard labor and disease to go around, these men had reason to smile when they were allowed to perform the occasional concert. Alf Binnie is at middle right.

Alf in a photo taken of his POW camp band, Jimmy Culley and the Stalagians.

One of those “brothers” was Alf Binnie, a guitar-playing Canadian pilot serving in Britain’s Royal Air Force. He’d recently marked the one-year anniversary of being shot down over Holland, and just a few weeks before this rare performance, Binnie had miraculously acquired a new handmade archtop guitar from a music store in Weimar, Germany. Acquiring a good guitar is special for any guitarist, but for Binnie it was part and parcel of how he survived the most grueling trial of his life. Somehow, the guitar survived too.

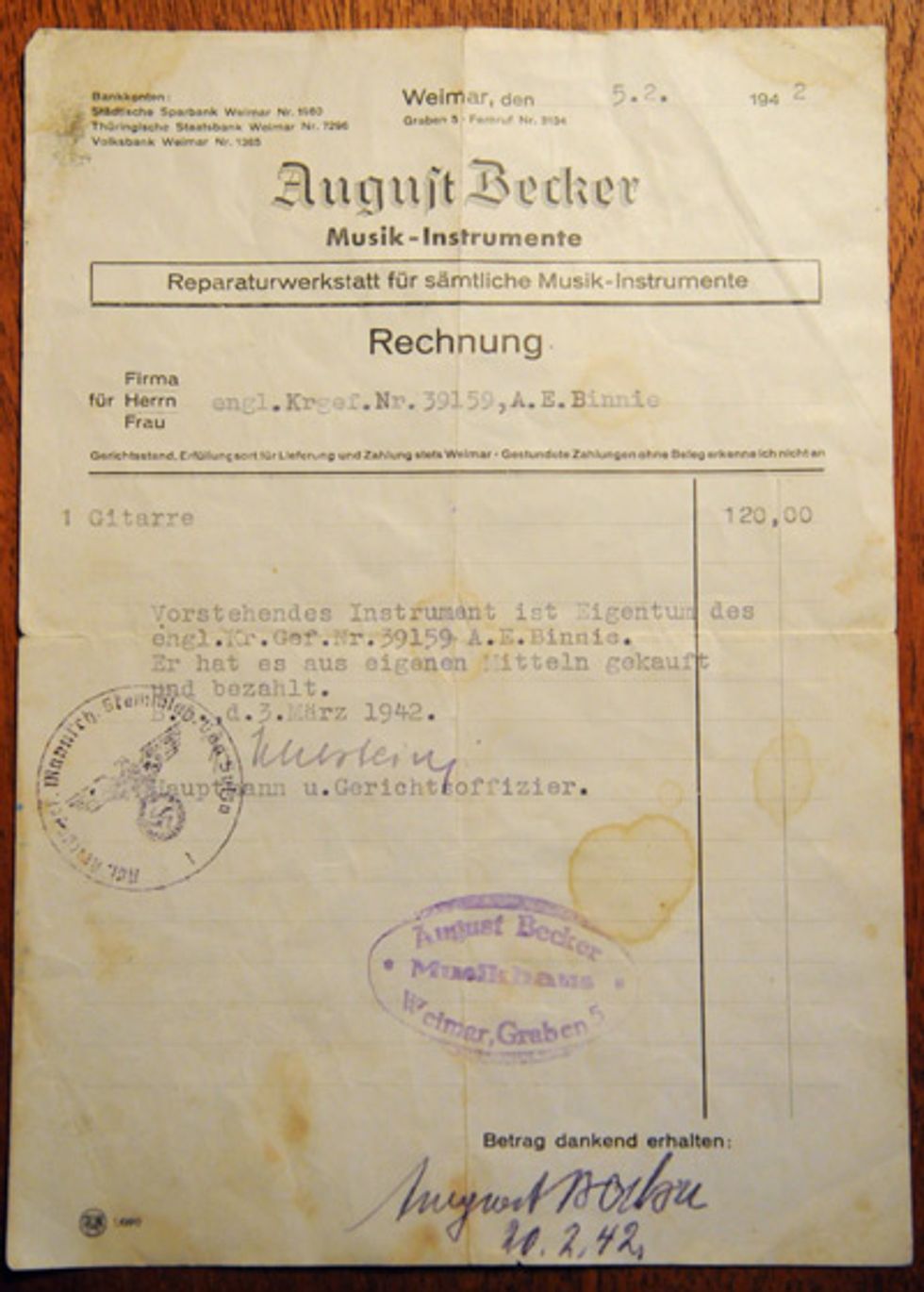

The story of Binnie’s POW guitar came to light earlier this year in the tiny Daily Inter Lake newspaper in Kalispell, Montana. An editor there became aware of Leslie Collins, a real estate agent in nearby Whitefish who had been helping Alf ’s widow, Joan, find the best home for Alf ’s small, precious collection of wartime belongings. The collection, now in the possession of the Canadian War Museum, includes a poster from the Strike up the Band concert at Stalag IX-C, a photo of one of Alf ’s prison-camp bands, the original bill of sale for the guitar, and, most remarkably, the guitar Alf acquired in February of 1942. It stayed with him through four more prison camps and “The March,” during which thousands of POWs were forced out of their camps and sent hundreds of miles on foot to flee from the invading Russian army. We recently spoke with Collins and Joan Binnie to find out more about this remarkable story about a man and his guitar.

The receipt for Alf’s guitar, which was purchased for him by guards on the condition that he play for them.

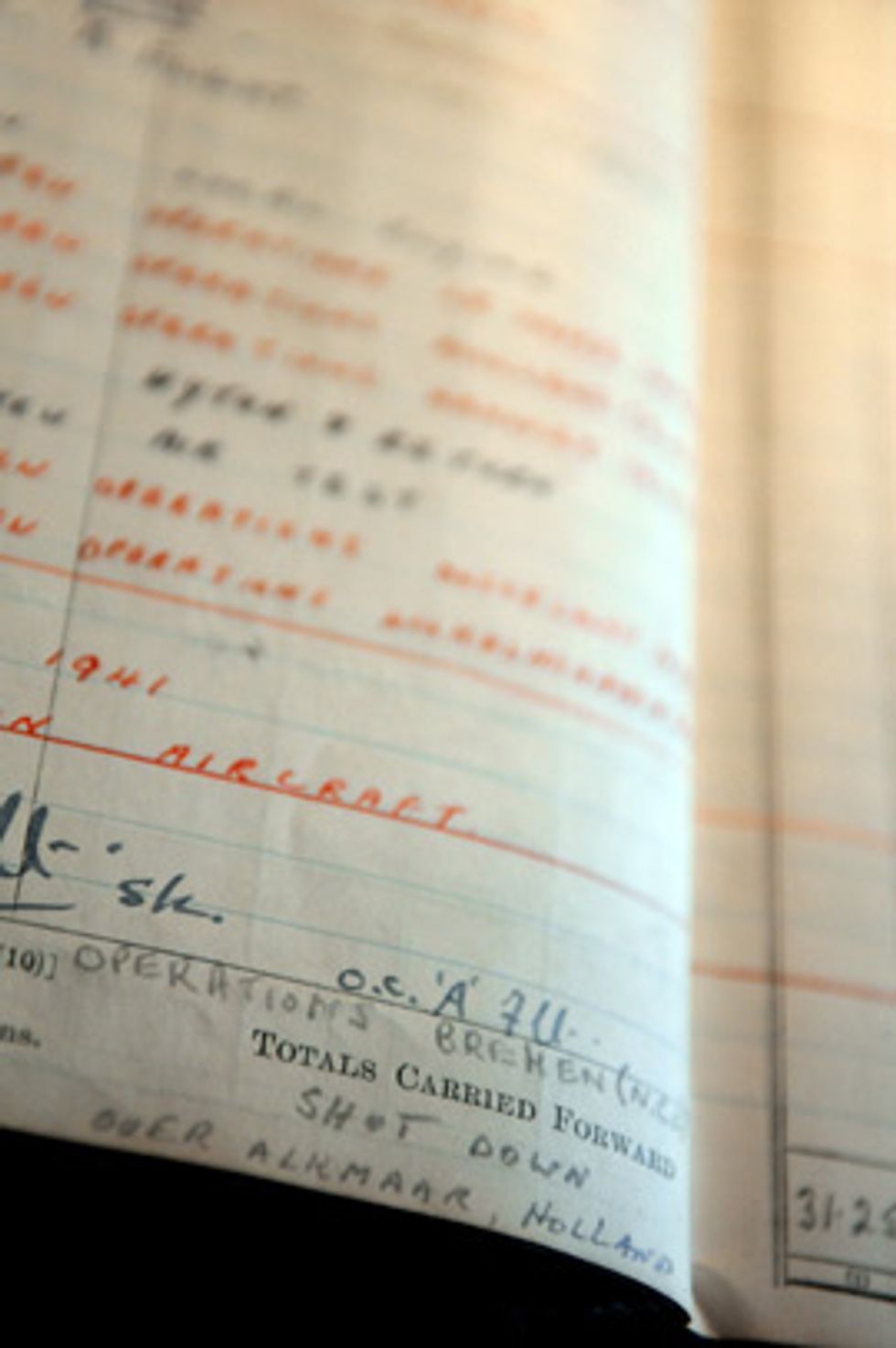

LEFT: The printed program from the April 26, 1942, Strike up the Band performance for the guards at Stalag IX-C. RIGHT: Alf’s pilot’s log indicates he was shot down on March 11, 1941, over Alkmaar, Holland. He was one of two survivors from his seven-man crew, but his leg was wounded badly and subsequently saved by German doctors.

More Adventure Than He Bargained For

Alfred E. Binnie was born in Montreal, Quebec, on January 6, 1920. His father, a reporter for the Montreal Star, was also the long-time organist and choirmaster for a large church. Joan believes Alf had a ukulele as a boy and perhaps a guitar, and he was an avid fan of Django Reinhardt and Louis Armstrong. Apparently Alf never harbored a desire to become a professional musician. When pressed to find work during his teenage years, he opted for adventure and a short-term commission in the Royal Air Force of Great Britain, an option open to Canadian citizens. By the time he got to England in 1939, the Germans were on the march across Europe, and in September, Britain and France formally declared war on the Nazi regime. Alf ’s program was suddenly eliminated, but with some persuading and patience, he was accepted into the RAF as an officer and pilot in training. By 1941, he was co-piloting missions in a Vickers Wellington Mk II bomber.

It’s unclear how many missions Alf flew before he was shot down, but it wasn’t many. On March 12, 1941, his plane took enemy fire and, with a badly wounded leg, he bailed out over Holland. Only one of his fellow crewmen survived. Alf managed to bury his parachute and walk to a farmhouse, where a family called a doctor. After looking at Alf ’s wounds, the doctor said there was no alternative but to call the German authorities, both to get access to a proper hospital and to ensure the family wasn’t called out for harboring an enemy combatant. Joan Binnie says the Nazis showed surprising respect and compassion for enemy officers and pilots. The next three months in the German-run hospital were agonizing, but several surgeries did manage to save Alf ’s leg. When he’d recuperated, he was processed in the German city of Oberursel and then sent to Stalag IX-C.

A British government public-domain photo of a Vickers Wellington Mk II bomber like the one Alf

began piloting for the Royal Air Force in 1941. He was shot down, captured, and given

medical treatment for his wounds in March of that year.

The prison camp was part of a complex that held as many as 47,000 inmates in horribly overcrowded conditions. Some reports say as many as 150 people lived and ate in 120' x 60' rooms. Prisoners were sent to work daily in nearby salt mines and stone quarries. Disease was rampant, and Joan Binnie says Alf felt fortunate to have never gotten dysentery, which was commonplace. Alf also avoided the hardest manual labor by virtue of being an officer. But he didn’t escape the prison’s ghastly dentistry, on one occasion having the wrong tooth pulled before passing out. “They (also) gave them very little to eat, which was very hard on them,” Joan says. “Mostly just soup and hard bread. I asked Alf how they managed to exist, and he said it was only because they were so young. Nineteen or 20. He said you could take a heck of a lot [at that age].”

Alf’s guitar features a bound headstock with a handsomely aged pearloid veneer that, unfortunately,

bears no labels or marks to indicate who made it. Note the well-worn tuning buttons and the zero fret.

A Light in the Dark

Alf ’s 6-string deliverance was made possible by a remarkably unusual circumstance—at least for a jazz musician: He didn’t smoke. Cigarettes were literally currency in the camp, and inmates could either smoke their meager tobacco rations or use them to buy personal effects. Somehow (Joan attributes it to a particularly compassionate camp commandant), Alf ’s desire to spend his saved-up cigarettes on a guitar moved up the chain of command and was approved. A prison guard apparently bought it on his behalf. The receipt from the August Becker Musical Instrument shop specifically notes that “The aforementioned instrument is the property of A.E. Binnie (inmate 39159). He has bought and paid for it out of his own means, or resources.”

When Alf got the guitar, says Joan, he “just about fainted. Because it was a beautiful thing and it was just handed to him. He was absolutely floored.” It was a copy of a Gibson L series, but nobody has been able to find a maker’s mark on it, so its provenance is unknown. A luthier who repaired its neck after the war said it is a very fine instrument. One can only imagine the solace and the relief from boredom such an instrument could afford. Not to mention the camaraderie that came from being able to form bands, which—according to accounts and photographs—was not uncommon. Performances, however, were rare, and life in camp was interrupted by lockdowns after escape attempts and outbreaks of disease. But it does seem that Alf was able to keep the guitar and play it basically when he felt like it. Joan relates that, at some point, Alf ran out of guitar strings and his father corresponded with one of the Dorsey Brothers (a popular jazz group from the 1920s and ’30s that was fronted by Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey), who helped arrange for delivery of a care package that included new strings.

At some point, Alf’s guitar—a copy of a Gibson L series archtop— was damaged and the neck needed to be rebuilt. According to his widow, Joan, the Canadian luthier who repaired it said it was a quality instrument.

LEFT: A detail shot of the supple carves on the back of Alf’s guitar. RIGHT: A close-up of a hairline crack that runs parallel to the strings all the way from the f-hole to the anchor of the trapeze tailpiece. Note the clean,

art-deco-like lines of the adjustable saddle piece.

The latter stages of the war should have meant the worst was over, but the opposite was true: Russian troops had purged the Nazis from their homeland and were marching west, liberating countries in eastern Europe as they went. This led to a frenzied evacuation of prison camps all over Poland, Czechoslovakia, and eastern Germany. About 80,000 prisoners were sent on foot across hundreds of miles in the dead of the coldest winter in decades. Thousands died, some from starvation or exposure, others to friendly fire incidents when Allied planes strafed the columns of men they mistook for retreating German troops. Alf saw friends and comrades die in such a manner.

All this time, Alf kept his guitar slung on his back, covered with some of the inadequate clothes still in his possession. Rations were literally scavenged from fields and farms en route, and it was never enough. As his group reached Gresse, east of Hamburg, their long-awaited deliverance arrived.

“They were on the road, and it was miserable because it was wet and raining,” she says, “but all of a sudden the guards all left, and then they heard that the war had ended. He and this friend went into this small town and took this soldier’s motorcycle. The Americans were coming towards them, and they [the prisoners] were waving at them. They had a white flag. They stopped that first night at a German farmhouse and took a ham [from it]. They stayed in the barn and they weren’t bothered. But those guys were something—they took the ham, but they left cigarettes [as payment]!”

LEFT: The crack in the top of Alf’s guitar widens a bit as it approaches the binding, but it’s not bad for a guitar that survived both a POW camp and “The March” at the end of the war. RIGHT: The binding appears to be separating from the body a bit, but it’s otherwise in remarkably good condition.

Lifelong Companions

Alf recuperated in England and returned home to Canada, where despite his wounded leg he went back to his passion for skiing. He bought a small hotel and became chief ski instructor at a larger resort called Jasper in Quebec. That’s where he met Joan. “I was working in Montreal,” she says. “I went up every Friday.”

Although many things that brought back memories of life in Stalag IX-C were repugnant to Alf throughout the remainder of his life—for instance, he couldn’t stand the smell of boiled cabbage—his guitar stayed with him as a source of joy till the end. He had the neck repaired when he was back home, and he often played for hotel guests, sometimes alone and sometimes sitting in on informal jam sessions with musicians who came up for breaks from New York or Montreal. “It was romantic,” Joan recalls. “I don’t think I appreciated it enough at the time.”

Around 1950, Joan and Alf moved to a more practical life in Long Beach, California, where he became a real-estate appraiser for a bank. Upon retirement, they moved back to snowy climes in the town of Whitefish, Montana—near the Canadian border and more great skiing. Alf continued to love jazz and some hillbilly country, becoming a fan of Chet Atkins and Glen Campbell. He played the guitar until nearly the end of his life. Sometimes it would sit unused for a while, but then, says Joan, “All of a sudden, something would come on the radio or TV or something and he’d go upstairs. He’d play quite often by himself up there. He would rush up there to get it. I used to love when he did that. The guitar was a big part of his life—all of his life.”

Alf’s widow, Joan, whom he met while working as a ski instructor in Quebec.

The two later ran a small hotel where he often jammed with guests.