| Exclusive Video! Click here to watch an exclusive video interview with Jake. |

The video, “Ukulele weeps by Jake Shimabukuro,” had nearly seven million hits as of press time, and it features Shimabukuro playing an incredible interpretation of the Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” in the Strawberry Fields memorial section of New York’s Central Park (an area of the park near where John Lennon was assassinated). It was filmed in a single take and originally aired on the cable access show Midnight Ukulele Disco.

Shimabukuro’s fame spread rapidly. He was soon featured on Late Night with Conan O’Brien, and some began calling him the Jimi Hendrix of the ukulele. Now 34, Shimabukuro is one of the world’s greatest ukulele virtuosos, with an awe-inspiring technique that is especially apparent on his unaccompanied arrangements and excursions. And his repertoire is remarkably wide-reaching, too: He’s equally comfortable playing everything from pop to classical and reggae, and he’s done so alongside such notables as Yo-Yo Ma, Jimmy Buffet, and Ziggy Marley.

Peace Love Ukulele, Shimabukuro’s new album, features 10 tracks full of impressive playing. But the two biggest highlights are the stirring original, “Go for Broke”—a tribute to World War II veterans— and an orchestral-like solo rendition of Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” We chatted with Shimabukuro about the new album, how he managed to channel both Brian May and Freddie Mercury with his diminutive little axe, and how he’s transformed the light and simple ukulele into a seriously heavy instrument.

When did you start playing the uke?

|

When did you get serious about it?

When I was a teenager I started branching out, listening to a little bit of everything—rock ’n’ roll, jazz, classical, and blues—and I would try to mimic it all on the ukulele. That’s what led me to developing a different technique and approach to the instrument altogether. In the beginning, it was all by ear. But when I got into high school, I started getting some formal music training, learning about sight reading, theory, and composition.

How important was that training to your musicianship?

It has played a really huge role in my musical life. While the training helped me better understand what I was doing on the instrument, it made me not just a stronger ukulele player but a complete musician. And I’m still always trying to expand and challenge myself by discovering new things about music. The great thing about it is that, the more you learn, the more you realize how little you know. That’s the beauty of it—you can never know everything you want to know about music in a lifetime.

Your music is remarkably diverse. Who were some of your biggest influences?

I’m influenced by the guitar greats of all styles—Eddie Van Halen, Yngwie Malmsteen, Pat Metheny, Michael Hedges, Andrés Segovia. I’m also inspired by consummate musicians like [cellist] Yo-Yo Ma, [bassist and composer] Edgar Meyer, [banjoist] Béla Fleck, and [vocalist] Bobby McFerrin. But it’s actually not just music that informs my arranging, composing, and performing: Bruce Lee is a huge influence. His philosophy and approach to martial arts are valid in any art form—and even in life in general. Bill Cosby is also an influence, because of his ability to just be himself, to seem so natural and sincere in his performances. And Michael Jordan, whose vehicle was of course basketball, expressed himself in a way on the court that was just truly magical and that I find musically inspiring.

Let’s talk about technique. Do you use a pick, or do you play fingerstyle exclusively?

I got into picks for a while, because I listened to a lot of Al Di Meola and was so blown away with what he did with a pick—such fast lines and such clean, precise runs. But, to me, fingers really give music a lot more character and uniqueness. Think about it: Anyone can run out and buy the same pick as you, but no one can go out and buy your hand in a music store. So, I believe that using your fingers really brings something special to the table.

What type of ukuleles and tunings do you prefer?

I play with a traditional tenor ukulele tuning in which the two outer strings are higher than the two middle strings. The notes [1st string through 4th] are A, E, C, G, the lowest one being middle C.

What brand and model do you play, and what kind of strings are on it?

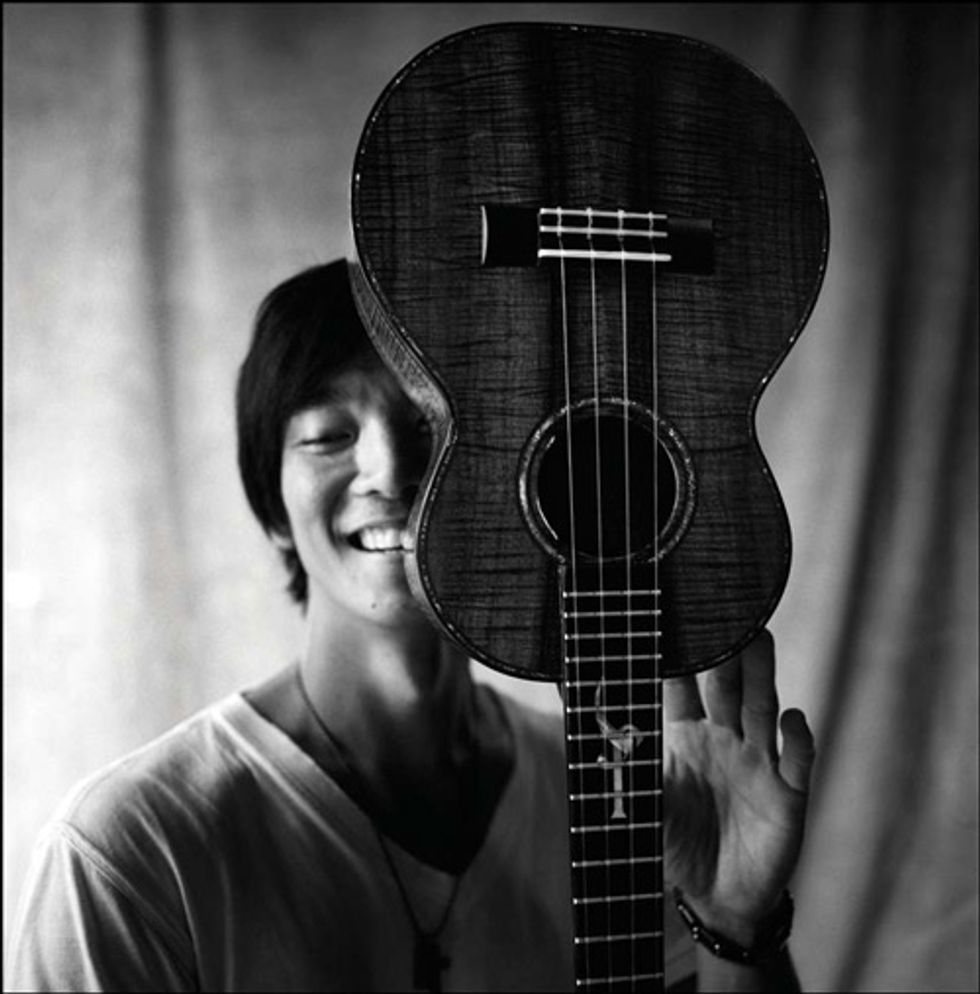

I play custom-made Kamaka ukuleles. It’s funny, because people are always wondering what specs I ask for in the instruments. But I know nothing about making instruments—that’s Kamaka’s area of expertise, so whenever they ask me what I want for my next ukulele, I just let them surprise me. And every time they make a new instrument, it’s truly amazing and exceeds my wildest expectations. It’s important to me to have a working relationship with a luthier, because there’s a certain kind of energy that goes into building an instrument. If that energy is intended for a specific player, then he or she will have a special bond with the instrument, and the music that comes out of it will be enhanced.

For strings, I use D’Addario’s J71 tenor uke set, the clear nylons with normal tension. I love those— they sound fantastic every time. They’re so consistent and very expressive, great for playing really soft or strumming hard. They are very sensitive, and that’s a really big deal because if I’m going for more of a piano sound, I need the strings to respond to the subtle things that I’m doing to shape the tone.

In 2006, Kamaka began making the limited-run Jake Shimabukuro Signature Model ukulele, which features a curly koa body, rosewood binding, and ebony fretboard and bridge. Each instrument sells for $5500 and takes 18 months to complete. All 100 have already been sold. Photo by Sencame

There are some great original tunes on Peace Love Ukulele. Can you describe your compositional process?

I’m a very simple person and I play a very simple instrument, so I normally start with one simple idea and turn that into several minute, even just one-minute expressions. The idea could be something I experienced in childhood, or it could be something that inspired me recently, or maybe even a chord voicing that I just discovered. Then, I’ll work around that one idea. I know it sounds so basic, but there have been instances when I’ve had a handful of ideas and tried to cram them all into one song. That’s tended to not work for me.

The covers are remarkable, too. How do you approach arranging?

I don’t just pick up my ukulele and arrange a tune. It would be easy enough to put together a melody line and some chords, but whenever I do an arrangement it’s not just about making a tune recognizable—it’s about doing something that makes it unique to the ukulele. It wouldn’t make sense for me to make an arrangement that could be replicated on any other instrument. A lot of my arranging strategy has to do with using the high 4th string—perhaps making an unusual cluster chord or playing the melody by bouncing back and forth between the 1st and 4th strings so they kind of ring over each other. Basically, in arranging I try to find the least obvious way to do the most obvious thing.

Arranging “Bohemian Rhapsody” must have been quite difficult due to its complexity.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is such an epic tune. It was really tough, because it’s multilayered— and, with the ukulele, I’ve only got four strings and two octaves to work with. There are certain sections where the harmony gets very complicated, and there’s a lot of contrary motion going on. So trying to scale everything down to four strings was definitely an undertaking. In making the arrangement, there were many moments when I wished I had a couple more strings. But then I realized that, since the ukulele is such a simple instrument, I just needed to take the song and strip it down to its bones. So, I started by thinking about how the song might be played from beginning to end on a monophonic instrument, like a saxophone or trumpet. That was actually tricky, because there are a lot of areas in the song where it’s hard to separate the melody from the harmony. Once I had the bones in place, I fleshed out the arrangement by adding what I thought was essential. A lot of trial and error was involved. Luckily, since “Bohemian Rhapsody” is such a well-known song, I discovered that some of the more obvious parts could just be implied in the arrangement, as I sensed that listeners would fill in what was missing in their minds.

While your version of “Bohemian Rhapsody” is a solo interpretation, you’re playing with a band on most of the record. How do you approach those two contexts differently?

When I’m performing solo, I don’t always know exactly what’s going to happen but I know I can just go with whatever I’m feeling. But when I’m playing with my band, it’s like I’m in a relationship— I have to give and take and be sensitive to others’ needs. I have to remember that there are other musicians up there onstage with me who also want the same outcome: to create something beautiful that everyone can walk away from feeling like they’re in a better place than before the music started.

One of the other amazing things about playing in a band is that we hardly spend any time together and don’t know each other that well on a personal level, but because we share these moments that are so personal, so deep and heartfelt, we connect on a level that’s strangely deep. There’s nothing I wouldn’t do for those guys. They could call me up at three in the morning and say, “Hey, my car broke down,” and I’d be right there.

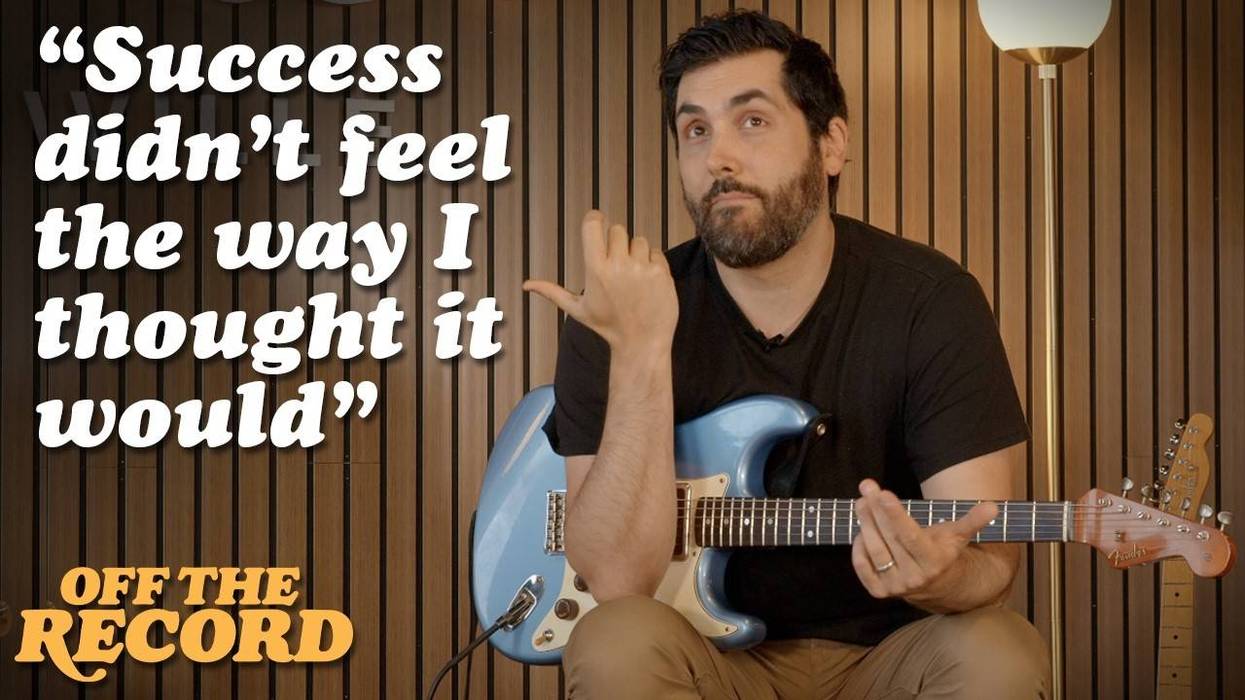

Shimabukuro’s custom Kamaka uke features abalone inlays of his initials across the

10th to 14th frets. Photo by Danny Clinch

In concert, you’ve been known to stretch out and improvise a bit.

Yes, I think improvisation is very important in music. It’s like having a conversation with someone you haven’t seen for a long time. You meet up at a coffee shop and just start talking. You have no idea what the other person’s going to say or what you’ll say—it’s all about just going with the moment. Ideally, each part of the conversation leads organically to the next. If music really is the universal language, then we should be able to spontaneously communicate with our audiences and with other musicians. That’s important because, through improvisation, everyone feels like they’re an indispensable part of the music. And, for me, that’s when the real meaningful stuff happens. It’s beautiful and heartfelt and honest and real—and exactly right for that moment.

Jake Shimabukuro's Gearbox

Ukuleles

Five custom-made Kamaka four-string tenor ukes that feature curly koa construction (top, back, and sides), ebony fretboard and bridge, rosewood binding, mother-of-pearl and abalone inlays, gold-plated Schaller tuners, and Fishman Acoustic Matrix Natural I pickups

Amplification

The Leon Audio Active DI Box

Strings

D’Addario Pro•Arté Tenor J71

Clear Nylon

Miscellaneous

Peterson StroboClip tuner