Intermediate

Beginner

- Explore the approaches and techniques which set the styles of B.B., Albert, and Freddie King apart.

- Discover how to learn from your heroes without knowing their actual licks.

- Learn how to turn up the heat to boost your playing’s emotional intensity.

In the world of Marvel Comics, the Avengers comprise the likes of Iron Man, Black Panther, and Thor, superheroes joining forces to wield a power even greater than the sum of its parts. What if we could incorporate this same idea into the world of blues guitar?

Today we’re going to find out, as we seek to combine the singular styles of three of the greatest blues guitarists of all time, all named King—B.B., Albert, and Freddie. While the surname remains the same, all three of their styles are distinct and instantly recognizable, with each legend bringing his own unique brand of blues justice (so to speak). B.B.’s Gibson ES-355-based “Lucille” allows him to seamlessly weave his understated but devastating magic; Albert bends the strings of his lefty-strung-righty, detuned Gibson Flying V seemingly without limit; Freddie unleashes cascades of relentless, stinging bends from “Lucy,” his trademark Gibson ES-345.

How Our Heroes Get Their Power

Each King generally draws their ideas from the tried and true blues scale (1–b3–4–b5–5–b7), essentially the minor pentatonic scale with the flatted fifth added, at times including phrases born out of the major pentatonic scale (1–2–3–5–6). So, it’s not as much their choice of notes that clearly distinguishes their styles, as it is how they execute these notes with their picking hand. B.B. used a standard pick, digging in when needed.

Albert wielded his blues power by primarily plucking with his thumb.

Freddie played exclusively with his thumb and index finger, often employing metal fingerpicks to create his signature sting.

Ex. 1 illustrates how B.B. might approach playing over an up-tempo blues shuffle.

B.B. would often use his first finger to bend notes on the 1st string, as in beat 1 of measure three. Moreover, try to capture his signature “butterfly” vibrato by quickly rotating your fretting-hand wrist.

Ex. 2 employs an Albert-style approach to the same groove.

Albert achieved his legendary wide bends, like those in measure one, mainly by detuning his guitar (low to high: C–F–C–F–A–D) while playing it upside-down. He would bend strings by pulling them down towards the floor, giving him additional leverage. Albert would have surely played Ex. 2’s bends on the first string, but using standard tuning, we can approximate by choosing a position which better work for us. Here’s a terrific view of Albert’s bends, as his disciple, Stevie Ray Vaughan, handles rhythm duties.

Ex. 3 shows how Freddie might approach this situation.

More than anything else, we’ve got to ratchet up the intensity here. So, don’t be afraid to dig in with your pick or fingers, whichever method you use. But be careful when turning up the intensity not to rush things, which is a common tendency. Watch as Freddie takes his time, milking one bend for all it’s got, then turning up the heat even more. They didn’t call him the “Texas Cannonball” for nothing.

Combining the Trio’s Strengths

Now, could we simply string a few of each of the Kings’ licks together to create a cohesive solo? Sure, but that would almost certainly limit our creativity. So, instead, let’s focus on incorporating their general approaches into our playing, rather than simply making off with a few of their licks (though we can absolutely use elements of those as well). Just keep in mind that each of these legends has a distinct attitude in their playing, which we can tap into to boost our own spiciness.

Next, let’s change things up with more of a mid-tempo blues groove. Here’s B.B., a master of using space, starting off by taking time to breathe between each of his languid phrases, creating tension using short silences, before moving on.

Ex. 4, exploits B.B.’s use of space, while incorporating Albert’s compound bends (those which are wider than a whole-step). Measure three also incorporates a wide Albert-style vibrato, which can be executed by pulling down to more closely emulate his sound. Here, SRV does just that, in front of the man himself.

Next let’s add some of Freddie’s intensity into the mix for Ex. 5 (measure two), while our final phrase pairs a descending B.B.-style lick with a wide bend reminiscent of Albert. For the initial nasty ghost bend, where only the release is heard, catch both the 2nd and 3rd strings with your fretting-hand ring finger before striking. This was an Albert favorite that SRV later adopted.

We can also incorporate some of the Kings’ favorite melodic approaches. For example, Albert would very often move the classic blues box up two frets in order to play over the V chord. Here he is to demonstrate:

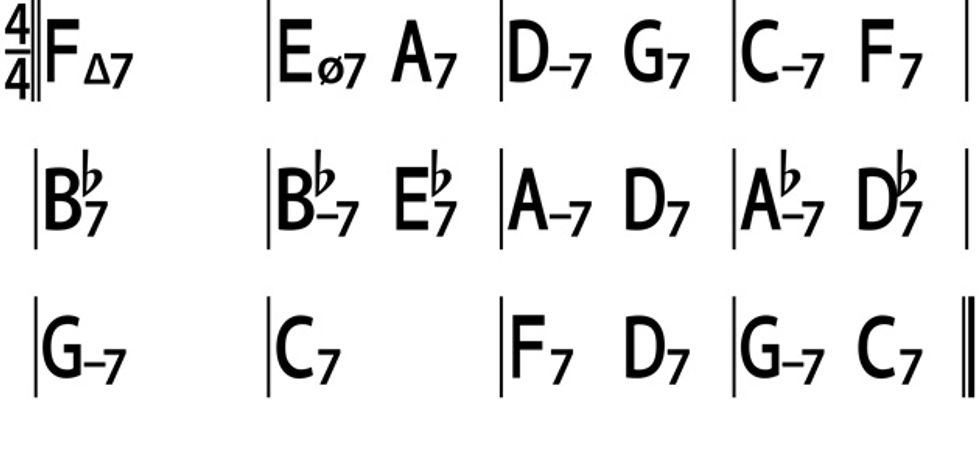

So, for the G blues excerpt in Ex. 6, Albert would use almost certainly use A minor pentatonic (A–C–D–E–G) over the V chord, D9 (D–F#–A–C–E). This would enable him to target some of D7’s chord tones, notably the 5 (A), b7 (C) and 9 (E), which we do in the example.

In measure one, we’re simultaneously employing this melodic approach, melding Albert’s and Freddie’s bending styles, and simulating both of their sharp picking-hand attacks. Regardless if you’re using a pick or not, pluck all the notes in measure one, up to the rest on beat 4, with your middle finger, pulling the string slightly outward so it snaps sharply against the frets when released. There’s plenty of space a là B.B in measures three and four, plus we’ve included his signature high root-note (G) punctuation at the end. He often let it hang in the air, but here we’ve kept it short.

Another melodic approach we can incorporate is B.B.’s penchant for subtly mixing and matching notes of the major and minor pentatonic scales. Here’s he is doing just that.

For Ex. 7, we’re going to stay in one of B.B.’s favorite pentatonic scale positions (the one he uses in the previous video, albeit in the key of Ab). We’ll sneakily mash up the major and minor pentatonic scales, while injecting a classic Freddie-style bend with wide vibrato. Note the presence of both F#, the 6, from the major pentatonic scale and G, the b7, from the minor pentatonic (or blues) scale.

Regardless of style, you can harness the attitudes and approaches of your favorite guitarists without actually learning their licks. Taking this macro view of playing allows you to use their greatness as a springboard for your own creativity.