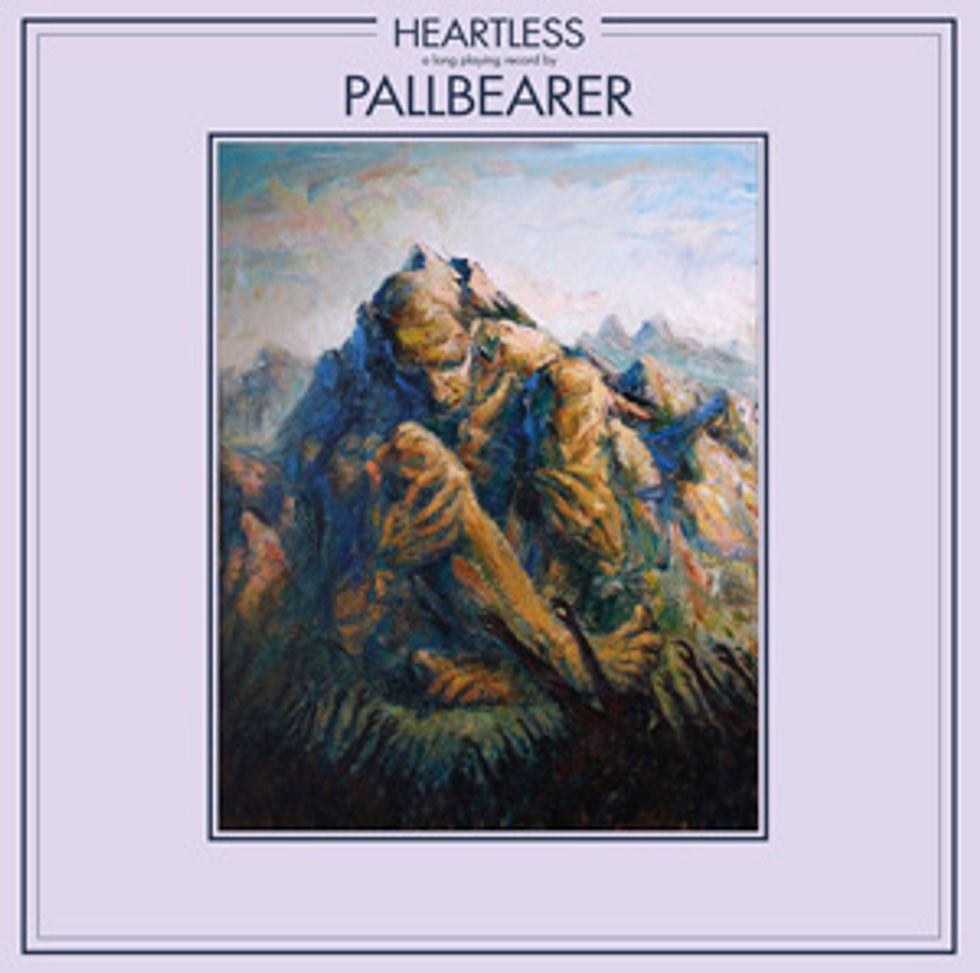

Metal, more than any other type of music, is overrun with labels and subgenres. Some are derived from a sound, like speed metal (Motörhead and Accept) or groove metal (Pantera and Sepultura). Others are based on where a band is from, like Norwegian black metal (Mayhem and Immortal) or Kawaii metal (Babymetal). And then there’s odd-timed mathcore (Converge and the Dillinger Escape Plan) and glam-metal (the terrain of legends Mötley Crüe). These labels are great for shorthand musical descriptions in the blistering-fast information age, but some bands are too fluid for shallow, rigid tags. Enter Pallbearer.

The Arkansas-based quartet crashed the metal party with their rumbling, doom-heavy 2012 debut, Sorrow and Extinction. That first salvo showcased a healthy dose of dynamics and melody—such as in the brooding, 12-minute “Foreigner”—by incorporating soaring guitar harmonies and acoustic intros not often associated with such a dark, indomitable sound.

“We’ve never been an ‘amp worship’ doom band that hammers on the same note or riff for minutes,” explains guitarist Devin Holt.

Produced by Billy Anderson, who’s cut tracks with Sleep, Neurosis, Melvins, and more, Pallbearer’s second release, 2014’s Foundations of Burden, displayed an even greater expansion of their sonic textures. The addition of cleaner, more present vocals, ambient passages and sections with piano, and doses of spelunking reverb helped provide a musical narrative flow that was compelling, evocative, and more coherent. (Also, as you’ll read later, Anderson showed the guys how to properly layer their dense guitar tracks for more air.)

Now Heartless is the band’s latest voyage, and it finds them still moving mountains with volume and refusing to be stagnant—resulting in their most expressive, powerful work. Growth and experimentation are evident in spots like the title track, which colorfully sprawls into a jazzy drum break (think French prog-rockers Magma) before careening back to full force at the song’s midpoint with a slightly out-of-phase, swirling guitar solo. On “Cruel Road,” Pallbearer cranks its tempo up to Judas Priest speed. But perk up, doomers! The album is packed with plenty of thunderous riffing, like the epic center of the symphonically rich “Dancing in Madness” and the twin guitar harmonies that propel “I Saw the End.” Although the group’s name is derived from a role indelibly linked to the ominousness of death, Heartless shows a band that’s never sounded more alive.

“A collection of songs like this is indicative of where we are as musicians and people, because this is our most diverse and complex album,” asserts guitarist-singer Brett Campbell. “Performance-wise and lyrically, we could not have made this album two or three years ago.”

PG recently spoke with Campbell and Holt at their homes, before the group headed out on tour. They detailed how Arkansas plays into their sound, how their guitar work on Heartless saw a role reversal, and what piece of gear Campbell can’t live without—but would never endorse.

What was it like recording your new album at home in Arkansas?

Brett Campbell: Just being comfortable gave us an added edge. The last time we recorded in Portland with Billy Anderson, we stayed in the studio where they had no bed, no showers, and I used a large block of sound-dampening foam as my mattress [laughs], which was actually okay to sleep on. Having the ability to break out for the day, grab a beer with a friend, and just decompress at home allowed us to be more focused. Which was great, because this material is really intricate and complex, so we had to be on it day in and day out. And on top of that, we saved money by not having to eat out for every meal or get a hotel, so that afforded us more studio time for working out parts. We even upgraded some of our gear.

Devin Holt: Our last album felt like a month-long repetition of Groundhog Day [laughs]. We basically worked 12- to 16-hour days and never left the studio except to eat. It was grueling and daunting—not to mention we ran into technical issues losing tracks or portions of songs. That was frustrating!

The band used the guitar-texturing tricks they learned from producer Billy Anderson when they decided to self-produce their new album, Heartless, at home in Arkansas.

Speaking of your homeland, how does Arkansas itself, the terrain and the region’s music scene, play into your sound?

Campbell: The attitude here is positive, and that fosters a feeling of mutual respect and freedom to chase interesting ideas and sounds. A pillar of the Arkansas metal scene with bands like Rwake [pronounced: wake—silent “R”], Deadbird, and Shitfire is how they all took the standard blues groove in sludge and doom and basically shot it into this acid nightmare. That proved to us we could do things our own way, too. As a burgeoning artist or guitarist, you always want to create your own thing or sound, but it can be intimidating seeing everyone and everything that came before. The lengths those bands took to make their creativity push the envelope showed me what it means to be fearless and determined.

Holt: Honestly, being from Arkansas might be one of the biggest influences or reflections of this band. Arkansas and even Little Rock are these killer, well-kept secrets that I selfishly don’t want anyone to know about [laughs] … because it’s affordable to live here, we have a booming arts scene, the music community is growing, but we’re all tight and supportive across all genres.

We grew up and cut our musical teeth at this Little Rock club called Downtown Music that really embraced metal and heavy bands, so we got to see and share bills with tons of groups. When we formed Pallbearer, Rwake’s [former] guitarist Chuck Schaaf played with us, so the tight-knit community and willingness to work together on several projects is what makes Little Rock’s metal vibe small-but-mighty. Arkansas is definitely intertwined sonically in all its bands.

Devin, how would you describe that Arkansas sound?

Holt: It’s a dirty, heavy, redneck psychedelic vibe not really felt or heard anywhere else. It’s basically like you had too many hallucinogenic drugs, but not like clean or pure ones like mushrooms or acid where you feel a higher consciousness. I’m talking about drinking too much Robitussin, going outside and spotting a light in the woods that confuses you in an eerie, haunting way, yet you can’t help walking towards it, because it feels comforting. And that’s the Arkansas metal scene [laughs].

When going into the studio to cut Heartless, one goal was creating an album with sounds that could be generated by the band live. Hence, bassist Joe Rowland and Campbell occasionally swap off on keyboards.

Photo by David Medeiros

How did you come up with that brutal opening riff for “Thorns?”

Campbell: It was written as an experiment when I was at my parents’ house hanging out with my sister and we started talking about songwriting. I explained that you can write a heavy song on an acoustic, because it’s not about volume and distortion. It’s about attitude and feeling. So to prove my point, I grabbed my dad’s standard-tuned acoustic and just randomly played the notes that are the song’s opening riff. While I continued to bullshit with her, I came up with the second part and I knew I was onto something. Before I knew it, all the instrumentation—including drums, adding guitar distortion, and singing scratch vocals on GarageBand—was written for “Thorns” in less than 3 hours, which is extremely fast for me. That was definitely the fastest song I’ve written for Pallbearer.

“I Saw the End” and “Thorns” clock in at under 7 minutes, which is short for you guys. Was there a premeditated goal to do that?

Campbell: It might sound counterintuitive, but I really challenged myself to come up with some ideas that implemented the Pallbearer sound, but in a condensed, fully thought-out package. With our slower pace, it’s actually pretty easy to write a song that comes out over 10 minutes, so I definitely tried to come up with a song or two that were much shorter than what people are used to, but still retains our vibe and has our core elements.

sounds like that.” —Brett Campbell

And the main guitar riff and harmony for our new album’s first single, “I Saw the End,” was written during the time period of our debut album, Sorrow and Extinction, but we fleshed out a few more of the song’s sections during rehearsals. The story felt complete with all the Pallbearer elements, so we included it in this cycle. When I went online to see people’s reaction to the song, a lot of comments were, “Pallbearer is going in a new direction and they’ve really changed their sound.” I laughed to myself because a lot of that song, at least guitar-wise, is based on an idea 6-plus-years old.

And then, on the flipside, there’s “A Plea for Understanding.” How do you go about building a seamless 13-minute giant like that?

Campbell: Lots and lots of editing, rearranging, and patience [laughs]. The first, slow riff that starts off “A Plea for Understanding” was one of Devin’s ideas. I was just blown away by it so we kept watering that idea. That intro riff really inspired me, so I went on a writing tangent for that song because I wanted to be a part of it. It originally was closer to 20 minutes, but we always try to keep our songs as succinct as possible. Even if it ends up being really long, we try to avoid having it go on for days just because we can. That sort of songwriting is just lazy and boring to me.

The long, sweeping epics are actually in my wheelhouse because those linear songs are what I’ve written since I started playing music. I look at those big songs like a puzzle. I start with this idea and I want to end up at a completely different spot and vibe. The fun part as a songwriter is figuring out how you’re going to connect the beginning that sounds like this to the end that sounds like that. My goal is to make everything flow, feel musical, and be a song without making parts or sections that are easily distinguishable just because it’s a different riff.

Brett Campbell’s Gear

GuitarsPRS S2 Vela (recently stolen) PRS SE 277 Baritone 1978 Gibson Les Paul Custom (borrowed from PG contributor Jordan Wagner) 1980s Peavey Predator

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Mark IV

Ampeg 4x12 loaded with 150-watt Eminence Swamp Thangs

Fender Pro Twin

Effects

EarthQuaker Devices Hoof fuzz

EarthQuaker Devices Arrows preamp/booster

EarthQuaker Devices Afterneath reverb

EarthQuaker Devices Tone Job EQ/boost

EarthQuaker Devices Levitation reverb

EarthQuaker Devices Avalanche Run stereo delay

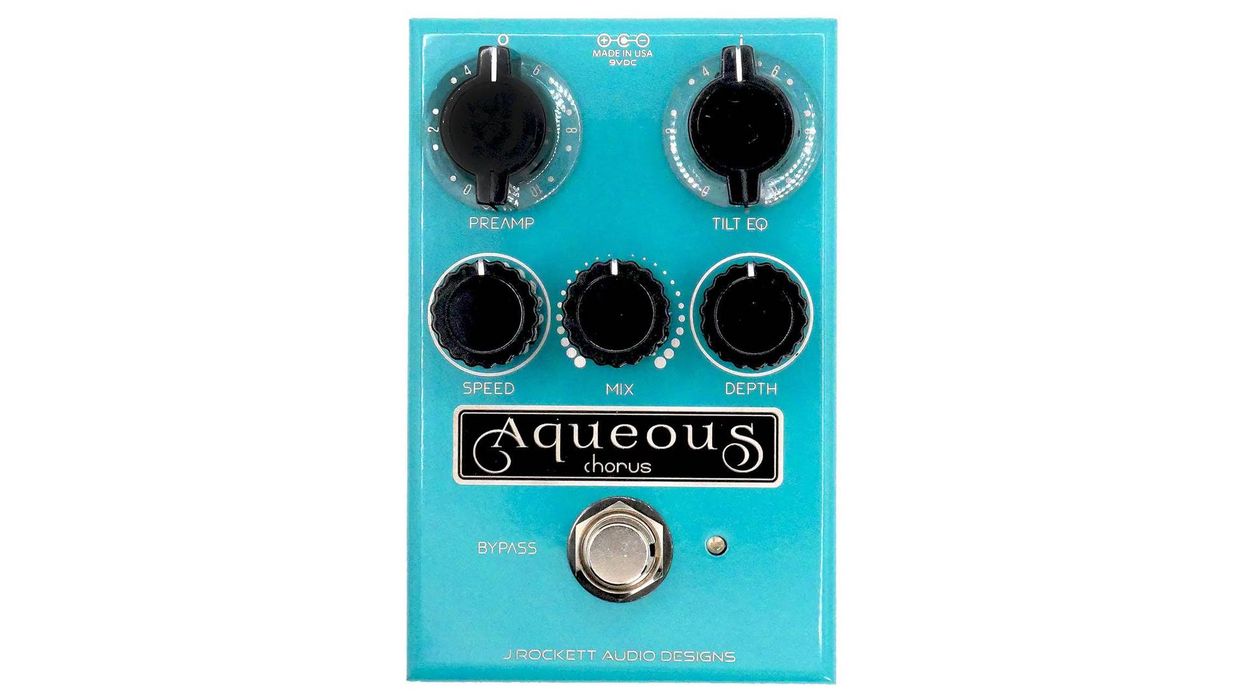

Strymon Ola dBucket Chorus & Vibrato

Smallsound/Bigsound Hawk Fuzz

Boss ME-50B Bass Multi-Effects

Black Arts Toneworks Black Forest overdrive

Catalinbread Naga Viper treble booster

LDP Nu-Tron II phaser

ZVEX Lo-Fi Junky chorus/vibrato/modulation

Synths/Keyboards

Dave Smith Instruments Mopho x4

Dave Smith Instruments Tetra

Roland JD-Xi

Strings and Picks

Stringjoy (various gauges)

Dunlop .60 mm picks

Devin, much of “A Plea for Understanding” is based on a riff that’s sort of outside your normal mode of operation, since you’re the band’s “shredder.” Where did that come from?

Holt: After the big keyboard break in “A Plea for Understanding,” there’s a David Gilmour-y solo

that normally would be reserved for Brett, but he wrote the key parts so we were jamming it out. I just messed around and winged a solo so we’d have something to listen to during playback. Brett and the rest of the band liked my version so much that we ultimately recorded my parts for that solo

in his song.

Are you both trying to work on things you

don’t do well or the other member seemingly does better?

Holt: When our first album came out, I wasn’t really serious about it. I mean, I’m a dude from Arkansas and nobody makes it, so I was still focusing on school, part-time jobs, and just took this band more as a hobby than a real career. A few years ago, I realized that we might not be a huge band, but we could certainly do this and not have to work any crap jobs on the side, so I knuckled down and starting taking lessons in jazz, and studying theory and chord shapes, and

getting really into comping and improvising. And now I’ve been teaching guitar and I’ve actually learned quite a bit and refined a lot of my

technique just because a lot of my focus with younger students is on the basics and fundamentals. I think the best way to get better overall, at anything, is to tackle the things you’re not as good at or don’t like as much because you can incorporate what you learn into things you’re already good at.

Campbell: It’s great to see how our playing styles have influenced each other. We just opened it up this time and each took stabs at solos that

normally would be reserved for the other guy. Sometimes it worked out like it had in the past, and sometimes he would outshine me—like the beginning of “Dancing in Madness” is all Devin. I don’t think he could’ve played that solo a few years ago, but he totally nailed it. Just like forcing myself to write shorter, full-on Pallbearer songs, I wanted to improve on my playing in areas where I’m lacking, like shredding or chaos solos. If you don’t ever challenge yourself or try something new, you’re never going to get any better. Going outside your comfort zone and routine leads to some interesting sources of inspiration.

Devin is such a clean player, so it used to make sense he tackled the faster, more technical solos. I wouldn’t say I’m sloppy, but I’m more into playing solos with bends and slides with a liquid feel to them. I generally approach solos or guitar parts as if they were played by a synthesizer, where you can have glide effects that let you sustain a note and have it melt into the next one.

What did you learn from working with Billy Anderson?

Campbell: He showed us his system of recording dirty-cleans, which are very lightly distorted guitar tones that you mix in with the heavier, more distorted parts. You can really hear a difference in how our complex chords and tight picking ring out so much clearer on Foundations than it did on Sorrow. We found out quickly that if you’re using gobs of distortion and then you’re layering those tracks, note definition is lost and your tone is muddy and murky. I’ve always EQ’d our amps for recording to have one track that accentuates the low-end, and then another layer that was more midrange focused. Billy showed us the third layer to the equation and that’s using slightly distorted, treble-rich tones to brighten the high end, add clarity and sparkle, and make our notes stand out and sing more. It’s like one track was Judas Priest, another was early AC/DC, and the one for bass used Joe Rowland’s Verellen Meatsmoke, and that’s just for the low-end power.

Holt: Another thing he was on top of was tuning. You wouldn’t think how much a hassle one out-of-tune guitar track could be, but he suggested we use heavier strings than we’re used to and really pay attention to our guitars and make sure everything was tuned before we hit “record” every time.

Devin Holt has historically been the group’s shredder, but for Heartless, he and Campbell traded roles on several numbers. “The best way to get better overall, at anything, is to tackle the things you’re not as good at,” he observes.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Did you use mainly your touring rig to record?

Campbell: Yeah. It makes sense to use what you have because that is what people will see and hear live. Most of my guitar tones were recorded with my two PRS guitars—an S2 Vela and SE 277 Baritone—into my Mesa/Boogie Mark IV through this old Ampeg 4x12 cabinet that has really high headroom. I also used my Fender Pro Twin that reminds me of an old Sunn Model T. In a live setting where I can’t constantly be EQ-ing things, I have the Mesa dialed for the mids with an emphasis on lows, and then I use the Pro with some mids and then dial in the high-end treble for more clarity. We used our touring pedalboards, too.

Some of my favorite recorded leads and guitar tones are in “Lie of Survival.” I was lucky enough to get my hands on our friend [and PG contributor] Jordan Wagner’s 1978 Gibson Les Paul Custom silverburst for a few days. It has these old Tom Anderson humbuckers that just bark.

Holt: We definitely had a conversation about this very thing when we were deciding when and where to record. I felt that staying here and doing it in Arkansas would allow us to actually buy long-lasting, quality gear since we’d be saving money in our budget from not traveling, eating out every meal, or having to ship gear and equipment. I got a Rockerverb MKIII, Joe got his custom-made Verellen Meatsmoke, and Brett is loving his new Mesa/Boogie Mark IV, all thanks to financial planning [laughs]. Don’t get me wrong, it’s great to fiddle around in the studio and find cool sounds with gear the producer has or the studio owns, but what’s the point if you can’t recreate that part or sound?

Devin, you score any other new gear?

Holt: I recorded with some ESP 6-string baritones I’ve had a bit, but I got my hands on ESP’s 7-string baritones that I will be using on the spring and summer tours. The reason for the change to 7-string is because I wanted to challenge myself and it solved a problem I had, because I teach guitar lessons in standard tuning. So when I pick up a new trick or technique, and I want to apply it, I always have to mentally transpose it to baritone tuning, which isn’t that far off, but you don’t want to be in that calculated of a headspace when you’re jamming or improvising onstage. Switching to the 7-string allowed me to have a full standard-scale guitar, but then I still have the low seventh string that helps me go into Pallbearer-rhythm mode. And I tune it to A–E–A–D–G–B–E and Brett tunes to dropped-A, which is A–E–A–D–F#–B.

Also, my friend Alex Avedissian, out of Atlanta, has been building pickups for High on Fire, Iron Witch—he’s basically becoming the underground pickup maker for heavy bands. So I tried out a set of his custom-wound Railsplitter humbuckers that are tweaked for more power. I think the neck is going after a Classic ’57 tone and the bridge is tight and crispy.

Brett, you’ve been a longtime user of the Boss ME-50B, which is designed for bass. Why do you prefer that to the numerous guitar-specific units?

Campbell: I’m on my third one now, and I got my first one from a friend in 2007 because he hated how it sounded. At the time, I was playing in a noise-rock band and a lot of the effects and parameters on the 50B lent it to being a powerful tool in that context. I used it so much in that project that it kind of became my sound.

Devin Holt’s Gear

GuitarsESP LTD AW-7Bs with custom Avedissian pickups

Amps

Orange Rockerverb 100 MKIII

Orange Rockerverb 100 MKII

Orange PPC412 4x12 cabinet

Orange PPC212 2x12 cabinet w/Jensen Electric Lightning speakers

Effects

Boss TU-3

Strymon Zuma power supply

Strymon Ojai power supply

Strymon Ola dBucket Chorus & Vibrato

Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo

Strymon BigSky reverb

Ernie Ball VP JR Volume Pedal

Orange Two Stroke Boost/EQ

EarthQuaker Devices the Warden optical compressor

EarthQuaker Devices Gray Channel overdrive

EarthQuaker Devices Avalanche Run stereo delay

Mr. Black GilaMondo phaser

Dunlop CBM95 Cry Baby Mini Wah

Strings and Picks

Stringjoy Custom Baritone sets (.010, .014, .018, .028, .040, .052, .070)

Dunlop Tortex Sharp .73 mm picks

Couch guitar straps

I really like how the wah and whammy are voiced. The resonance setting is a big asset because it’s a secondary wah sound I like. It acts like a low-pass filter that sweeps on the higher registers. I like using the octave-up function for leads because it really helps pop out of the dense live mix. It

doesn’t track nearly as well with chords and it’s not a clean modulation, but I get this weird, glitchy splattering of shimmer that I really enjoy for “The Ghost I Used to Be.” Another thing it has is this chorus/delay setting that is my go-to solo echo effect, because it’s a warm, watery sound. That all being said for my sound and how it works for me, I do not recommend the pedal for guitarists [laughs]. Its idiosyncrasies work for me though.

Another new wrinkle I hear is revving up the tempos, like in “Cruel Road.”

Campbell: That song is our homage to Judas Priest and classic heavy metal. Recording the vocals was great fun, and it gave me a chance to channel my inner Halford [laughs]. It’s clearly at a faster tempo than we typically work in, which was somewhat challenging to make it still sound like

us, but I think it worked out in the end. I’m really pleased with my solo, because there is some bizarre shit happening. It sounds like a trade-off between me and Devin, but I did two different

takes on the same solo with vastly different guitar tones. With that, we used one guitar in the left channel for four measures and then switched to

the opposite guitar tone in the right channel. We did that back and forth a few times and it created this really disorienting effect, but also sounds really huge and thick. I love how the solo opens up with this guttural Godzilla roar [laughs].

Devin, I want to go back to your second album, Foundations of Burden, because I’m curious about the psychotic solo in the middle of “Watcher in the Dark.” What happened there?

Holt: Oh man, for that one I was playing my solo part as I intended through this long chain of pedals, and Brett and Joe were on the ground kicking on random pedals, turning knobs, and just causing mayhem at my feet [laughs]. Honestly, that was like a three-person solo because they were doing just as much as I was.

Why does the band like using unusual chord shapes?

Holt: A lot of doom bands really hang on and bang away with power chords or pentatonic things, but I think things sound fuller and more musical when we have a melody line going underneath the chord—normally the third moves the melody—and then there’s a lead on top of that, too. The key to the Pallbearer sound is our music is more powerful and fluid when we have a melody always pushing the song forward. We will use power chords, don’t get me wrong, but a lot of the times we’ll play off the sixth, seventh, or ninth. All the instruments in our band sing rather than get locked into that rhythmic pounding.

I honestly have more fun messing with modulation pedals, spacey reverb and delays, and playing clean tones than I do playing a heavy riff through raging amps. I know that’s not a very metal thing to say, but it’s true. We’re all huge fans of Yes and Pink Floyd, so it’s really just been a lifelong study of what David Gilmour was able to do in the studio and onstage. We definitely let our prog bleed through more than other doom or heavy bands.

YouTube It

“Thorns,” off Pallbearer’s new album Heartless, has grown from its humble acoustic-guitar-riff roots into a melodic, chug-powered, and artful slice of hard-to-classify power metal onstage, with big, harmonized guitar lines. Here, the band delivers the tune at the Howard Theatre in Washington, D.C., during an August 2016 show.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)