Chicago, IL (May 31, 2012) -- As one of the more criminally glossed-over guitar heroes of jazz-rock’s psychedelic heyday, Pete Cosey had an unflashy but unusual knack for making six strings sound like a thousand. When the news broke on May 30 of his death in Chicago at the age of 68, all those scorching leads may have gone silent, but the legacy Cosey left behind—including his classic late-’60s recordings with Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, and above all his groundbreaking fusion work with Miles Davis—will resonate among guitar heads for decades to come.

Pete Cosey onstage with Miles Davis circa 1973. Photo courtesy of Urve Kuusik / Sony Music Entertainment.

At his core, Cosey was a soul-blues player with an ear for Wes Montgomery, Freddie King, and the free-jazz underground. He was a session guitarist at Chess Records and an early member of Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), and sat in on AACM co-founder Phil Cohran’s 1968 tribute album The Malcolm X Memorial. That album featured onetime members of the proto-soul-jazz outfit The Pharaohs and later Earth, Wind & Fire. Cosey had an informal group with bassist/trombonist Louis Satterfield and drummer Maurice White that arose out of their collective work for Chess.

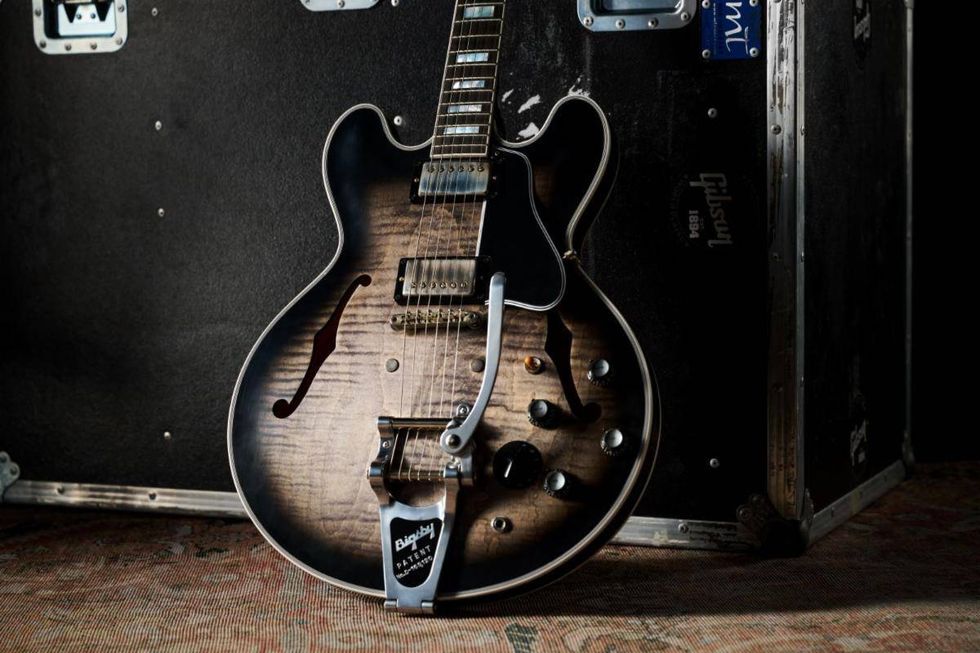

Cosey appeared on various Chess sides by Etta James, Fontella Bass, Rotary Connection, and more, but he really came to prominence on a series of albums coproduced by Marshall Chess that literally flipped the burgeoning electric blues-rock movement on its head. Muddy Waters’ Electric Mud, released in 1968, quickly offended stodgy blues purists and became a notable favorite of Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, and Eric Clapton for its way-out guitar work—work that happened to be Cosey playing a Gretsch (likely a 6128 Duo Jet) through all manner of wah, fuzz, and delay effects, including a Jordan Boss Tone fuzz/distortion and a Maestro Echoplex. “Herbert Harper’s Free Press News,” in particular, is an acid-rock tour de force of extreme guitar overdrive.

Cosey duplicated his keening acrobatics the following year on Waters’ After the Rain, and for Howlin’ Wolf on the equally controversial The Howlin' Wolf Album. The project was supposedly hated by Wolf himself, surging as it did with such mind-blowing psychedelic fugues as Cosey’s wah-Echoplex breakdown in “Smokestack Lightning”—a prime example of his natural affinity for charting otherworldly oceans of electronic sound.

“I had a really long beard during those days,” he told writer Bill Milkowski in 2007. “It was, like, down to the navel, and I’d sometimes braid it. So on one occasion during the session, Wolf walks up to me and says in that raspy voice of his, ‘Why don’t you take them wah-wahs and all that other shit and go throw it off into the lake on your way to the barbershop?’ I mean, he just wiped me out with one stroke, man! Covered all the territory—the long hair, the beard, the wah-wahs and the whole deal.”

Cosey with jazz saxophonist Dave Liebman in 2007. Photo © Nell Mulderry

Even so, Cosey’s eccentricities drew the attention of Miles Davis, who with 1972’s On the Corner had launched a focused assault on the barriers that separated jazz, rock, and Stockhausen-ish electronic experimentation. Cosey was primed for the switch: Not only had he grown beyond the traditional confines of the touring gun-for-hire (on prominent gigs with Aretha Franklin, Sonny Stitt, and, in the early ’70s, Chicago sax legend Gene Ammons), but along the way, he’d incorporated various tuning systems and progressively more space-age effects into his repertoire. Some of these—including the Mu-tron III envelope filter, the EMS Synthi A synthesizer, and the Synthi Hi-Fli—helped him expand further on the weird micro-tonalities he’d picked up from playing the sitar.

Cosey’s trial by fire with Miles began on the road in 1973. "The band settled down into a deep African thing,” Davis later wrote in his autobiography, “a deep African-American groove, with a lot of emphasis on drums and rhythm, and not on individual solos.” Despite being one of three guitarists—the others being Reggie Lucas and, in 1974, French axe-slinger Dominique Gaumont—Cosey shredded with an authority that stood out. From his customary seated position at stage right, he peeled off sky-slashing leads that, in true Hendrixian fashion, seemed to suggest a higher plane of being. Some of the best examples include the wild wah solo on “Wili (Part 2)” from 1974’s Dark Magus (likely done with a vintage Halifax wah, which was known for its wide sweep), his restrained and mournful wailing on “He Loved Him Madly” from 1974’s Get up with It, and the shattering, soul-buzzing phrases of Agharta’s “Prelude (Part 2)” from 1975.

“Pete had a really spiritual sound,” says Brooklyn bassist Melvin Gibbs, who in 1989 recruited Cosey to replace an outgoing Bill Frisell in the hard-funk fusion trio Power Tools, with drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. “That word is out of style these days, but it was really some Black music, in the sense of being super-positive and super-aggressive at the same time. His playing was all about transcending your situation and maximizing yourself to the highest level you could reach. And within the context of Miles’ music, which was really aggressive and in-your-face anyway, it just had a real power.”

Cosey played various guitars during his stint with Miles, among them a Fender Telecaster, a Fender Stratocaster, a Gibson Les Paul, and a Vox Phantom XII, which he usually plugged into Yamaha RA-200 amplifiers. Beyond the gear and the effects, it was his quirky, cosmic personality that defined his sound—as well, perhaps, as his descent into obscurity. After Miles Davis went into self-imposed retirement in 1975, Cosey’s appearances became sporadic. In 1983, producer Bill Laswell hired him to play on Herbie Hancock’s Future Shock, and again in 2000 for Fisherman’s.com with saxophonist Akira Sakata, Laswell on bass, and Hamid Drake on drums. He also recorded with Village Voice writer Greg Tate’s Burnt Sugar ensemble, Melvin Gibbs’ Elevated Entity collective, and composer/arranger Bob Belden’s Miles from India project.

In 2001, Cosey started his own group, the Children of Agharta, which featured former members of the Miles Davis electric lineups. Gibbs took part in some of the group’s New York performances, with rehearsals taking place at the home of Public Enemy’s Chuck D—an avowed fan of Electric Mud, as documented in the reunion of that album’s original backing band, including Cosey, in the Martin Scorsese series The Blues.

“When you talk to guys like Arto Lindsay and Henry Kaiser and Bob Quine,” Gibbs says, “all those downtown New York guitar players were directly influenced by what Pete was doing. And that makes me think about the fact that he was really bringing the noise before Public Enemy was. For me personally, it was all about that Afro-spiritual thing that he had—that was really important for that time and for guys of this era. Essentially, Pete Cosey was the original noise-bringer. What you hear is an expression of who he is—a certain way of being that goes beyond music.”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)