Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

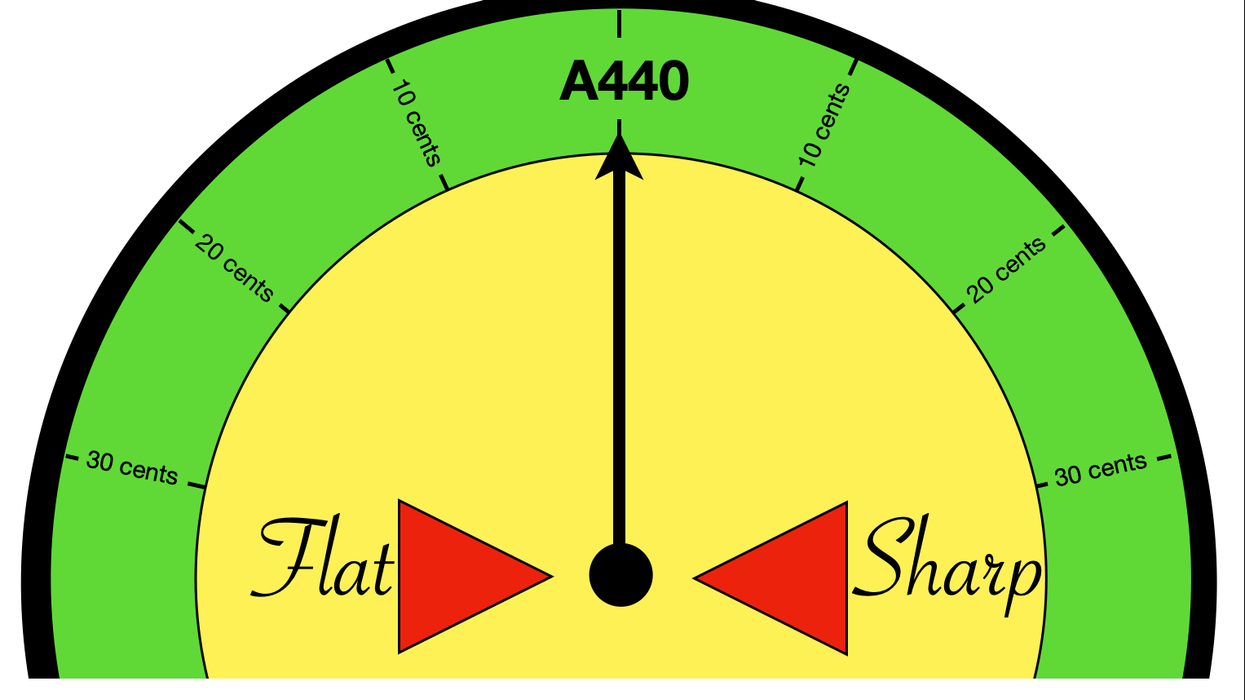

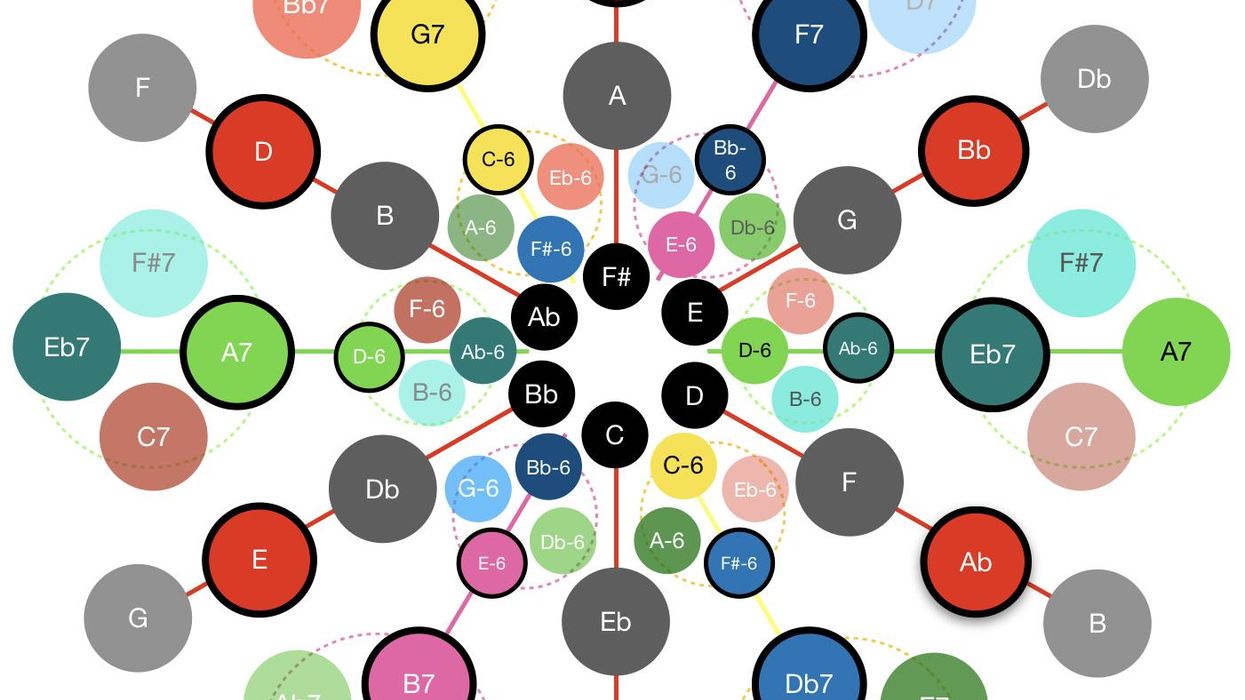

The Root of It All

Bass content focused on music theory.

Don’t Miss Out

Get the latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Popular

Recent

load more