A certain semi-famous (formerly über-famous)

pop star/folk musician recently said in my

presence that jazzers are the worst when it

comes to musical snobbery. “Heyyyyy, wait a

minute…” said I in a mock deeply offended

tone. One of my former students was there

to make the save by quickly saying, “Not you,

Jane.” Well, okay, then. But it seems it might

be a good time to examine that notion.

If you’re a jazz cat yourself, maybe you need

to answer these questions, too: Do you

ever play fingerstyle? That has its origin in

classical guitar. Do you ever use your right-hand

thumb for bass notes? That’s kind of

a country thing. Do you strum an acoustic

steel-string sometimes? Folkie. Do you play a

nylon-string? Classical and bossa nova.

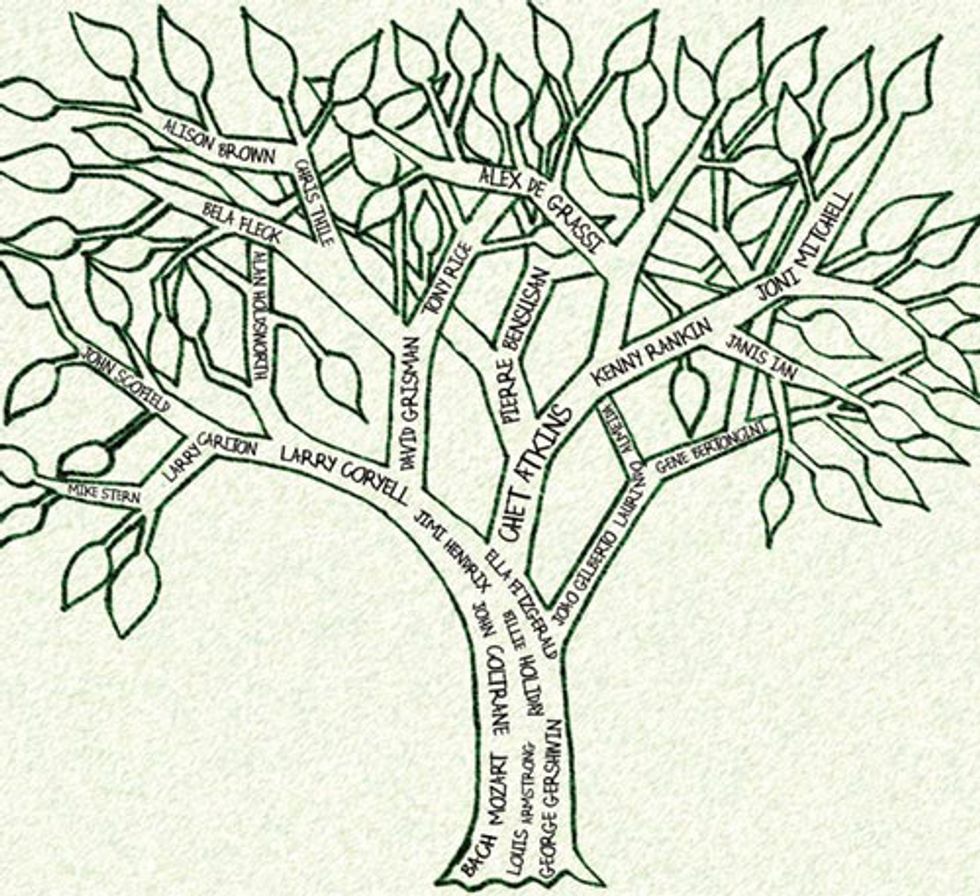

I like the word “fusion.” I especially like it as a

description of a musical style, including but not

limited to the jazz-meets-rock music from the

mid ’70s. That fusion spawned the work of guitarists

Larry Coryell, John Scofield, Mike Stern,

Allan Holdsworth, Larry Carlton, and a much

longer list of players that followed their lead in

their own way—some more jazz than rock, some

more rock than jazz. There’s also the fusion of

jazz and folk. Singers/guitarists Kenny Rankin,

Janis Ian, and Joni Mitchell come to mind, along

with the instrumentalists Alex de Grassi, Pierre

Bensusan, and for heaven’s sake, Chet Atkins.

Bossa nova is the result of the folk music of

Brazil fusing with American jazz. Check out João

Gilberto, Laurindo Almeida, and Gene Bertoncini

for their individual statements on that. Bluegrass

and jazz have fused all over the place. Guitarist

Tony Rice embraces jazz on a steel-string flattop

and was an integral voice in the “Dawg

Music” created by mandolinist David Grisman.

An update on that fusion has come by way of

contemporary music from mandolinist Chris Thile

and banjo virtuosos Béla Fleck and Alison Brown,

the latter of which also adds guitar to her blend.

What we play and what we listen to are not always the same. I’ve found that if you talk to jazz guitarists and ask what they like to listen to, you’ll be surprised by the diversity of styles that comes up. Find out what they’ve practiced over the years, and a similarly wide range of material comes to light. A few summers ago, I prepared for a solo guitar recital (played entirely on my nylon-string, by the way) by working on a classical piece every day—first thing in the morning and last thing at night. The rest of the day was reserved for my repertoire practice, but the classical piece kept me centered on the instrument, inspired by the guitar arrangement, and physically ready to play.

My old jazz box has one pickup. It’s my main axe. I have a smaller version—my secondary jazz box, if you will—that I use for teaching. That, too, has just one pickup. I’ve had, at various stages in my playing days, guitars with two pickups. I really tried, honest. I just couldn’t get comfortable with any sounds other than finding that one right place to leave the switch and the controls. So, I found my guitar niche. But that does not prevent me from pretending to be Larry Carlton playing the solos to Steely Dan recordings while I’m driving (I also pretend to be k.d. lang and Barbra Streisand sometimes…).

It is getting harder and harder to find musicians who have not been touched in some way or another by at least a few styles of music. Music appreciation is a form of diversity awareness. If you trace our roots back far enough, we’re all related. Trace back our musical roots and you’re likely to find Louis Armstrong, blues, George Gershwin, Mozart, Bach, African drumming. In my early days of learning and listening to music, I wanted to know all about the artists that I looked up to. I was a pop-culture child in the ’60s. Singer-songwriters spoke of Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Tony Bennett. So there I was, in the dusty record stores on beautiful summer days, finding the vinyl history of jazz standards to learn and memorize. Before Jimi Hendrix, Carlos Santana, or Jerry Garcia took extended, spiritually gifted solo statements in the moment, John Coltrane was speaking his truth through his saxophone.

If, in fact, we jazz guitarists have created a reputation for being snobs, then it’s time to outgrow that image. Anyone playing honest music with their whole selves in it, devoted and sincere, deserves our ears, encouragement, and applause.

Jane Miller

Jane Miller is a guitarist, composer, and arranger with roots in both jazz and folk. In addition to leading her own jazz instrumental quartet, she is in a working chamber jazz trio with saxophonist Cercie Miller and bassist David Clark. The Jane Miller Group has released three CDs on Jane’s label, Pink Bubble Records. Jane joined the Guitar Department faculty at Berklee College of Music in 1994.

janemillergroup.com