I recently had the pleasure of hearing Jazz Is Dead at the Newport Jazz Festival. Led by bassist Ali Shaheed Muhammed (A Tribe Called Quest) and composer/producer Adrian Younge, the band was formed to draw inspiration from such greats as Gary Bartz, Henry Franklin, Doug Carn, Roy Ayers, Jean Carne, Lonnie Liston Smith, and others in creating new compositions and fresh arrangements of their work. The irony behind the name and ethos of this band, though, is that jazz is certainly not dead!

The Newport Jazz Festival, founded in 1954 by jazz philanthropist Elaine Lorillard and artistic director George Wein, is one of the world’s oldest jazz festivals. Its stages have been graced by many, from John Coltrane to the Allman Brothers. Since 2016, Philadelphia bass luminary Christian McBride has served as the festival’s artistic director.

Anybody who has recently attended Newport or any other major jazz festival, such as the North Sea or Montreal Jazz fest, would probably agree that the rumors of jazz’s untimely demise are greatly exaggerated. But the music is changing. If that sounds contradictory, it’s just because the very nature of jazz—or “creative music,” as I prefer to call it—is change. Some of this music’s greatest exponents—Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Art Tatum, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Nina Simone—were responsible for bringing about some of its most significant shifts. They not only changed the music from what it was when they arrived, but, as in the cases of Coltrane, Miles, and others, also completely changed their own sounds every few years, to the point of being unrecognizable to their earlier fans.

Much of the meat is not in what is written or said but in what is experienced. We must put the next generation in front of the real elders and actual players as much as possible.

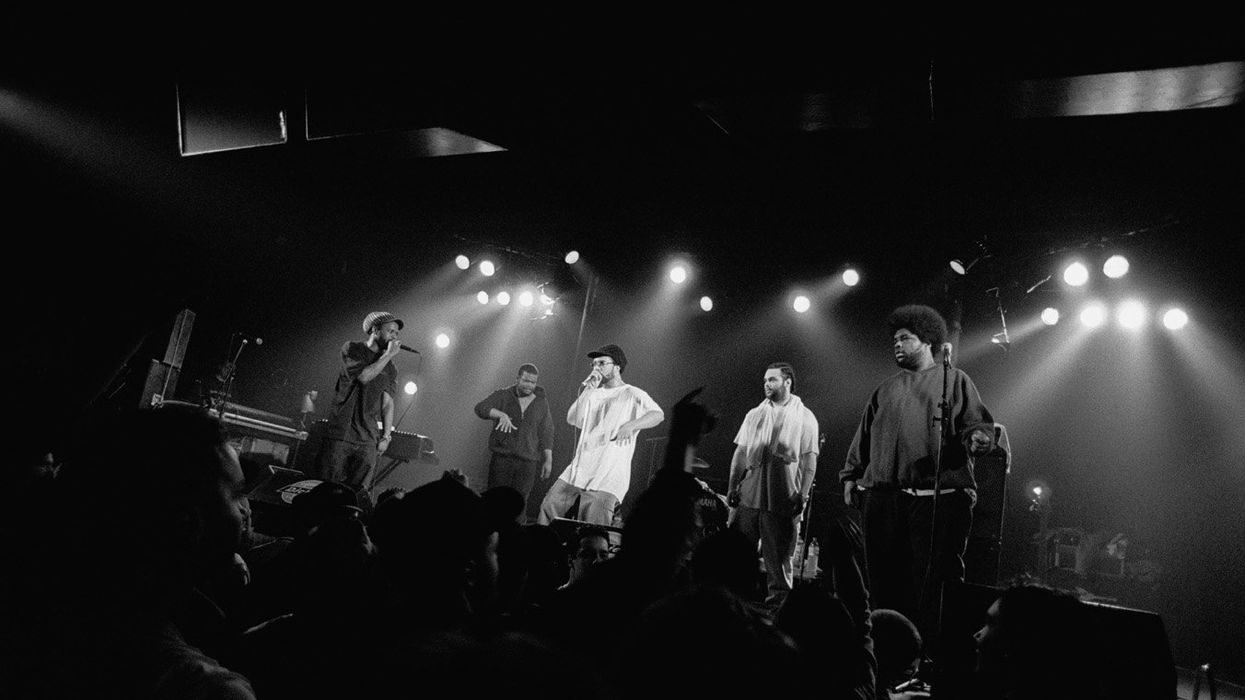

The big change in jazz is an overall change in culture that affects the way this music is learned, enjoyed, and passed on. For the vast majority of its existence, jazz has been a community-based music that arose primarily from African Americans. It was a music central to Black culture, which informed art, writings, philosophy, fashion, clubs, dance, etc. for decades. And like many Black musical traditions, jazz persisted as an oral tradition, where the next generation learned from the last in close proximity, and then, in turn, taught the next generation in the same way. This is not to say that some Black jazz musicians did not study formally. But even in these cases, the real jazz education took place through mentorship outside of the classroom. Young musicians often got their start by listening to recordings of the masters, following them around to clubs, and finally spending years playing in their bands before getting the opportunity to lead their own, where the cycle began anew.

In the case of musicians such as Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk, their bands were the universities. They all formed part of a thread that ran from Louis Armstrong to Wynton Marsalis, Elvin Jones to Marcus Gilmore, or Jimmy Smith to Joey DeFrancesco. But that thread has been frayed as mentorship was displaced by formal education.

University education, with its regimented methodology, standardized curriculums, statistics, rules, entrance requirements, privilege, certification, and, of course, associated tuition costs, quite literally changed the face of jazz, much like the gentrification of Harlem, Philadelphia, and Chicago now pushes inhabitants out of their own communities. Young children growing up in historically Black neighborhoods in the U.S. today, for the most part, feel very little connection to jazz and may never experience it live or even ever hold a musical instrument! So, maybe more primary-to-high-school jazz education would be a good thing.

But at the higher-education level, what can be done? Formal education has its place and excels when the goal is to distribute standardized information to a large group of people at one time. In the case of creative music, where the goal is to express oneself in a unique and recognizable way that is imbued with one’s personality, the mentorship approach once typical of the jazz community is vital. Much of the meat is not in what is written or said but in what is experienced. We must put the next generation in front of the real elders and actual players as much as possible. Let the younger generation see the elders play, tell stories, interact … and maybe some of the young musicians will even get to sit in. Foster the development of real relationships and exchange.

The jazz community has sadly lost many very important players—most recently guitarist Monnette Sudler and organist Joey DeFrancesco. But these players’ legacies live on through those they mentored, like a torch being carried forward. In the post-lockdown era, the scene may not be at its most vibrant, but it is coming back and there are plenty of players who are doing some really interesting things. Jazz is not dead.