When you get right down to it, there’s no formula or complex calculus for determining what makes one particular axe-slinger stand out from the crowd. Is it all in your technique, or is it all about that elusive feel? Do you have rock-star swagger, or are you the more cerebral type? Are you a badass riff machine, or can you solo circles around so-and-so?

Whatever the defining mojo really is, one thing we know for sure is that we know it when we hear it. There’s an unmistakable signature to a gritty Keith Richards riff or a kamikaze Jimi Hendrix solo. Strip it down to its basics, and most of what makes it memorable comes from the personal stamp of the guy doing the playing. But there’s something else afoot here. The magic isn’t just in what they’re playing or how they’re playing it—it’s in how all that interacts and intertwines with sonic signatures imparted by the gear they use.

Throughout the history of electric guitar, so much of that magical mojo has been spun from the electric innards of stompboxes—wah-wahs, phasers, flangers, envelope filters, fuzz units, and more. Effects pedals are the great democratizers: Get yourself a distortion box, and you too can be a rock star! But, more importantly, they’re portals to new worlds of tone. Anyone can use them, and anyone, with the right combination of devices, timing, and/or technique can get a sound out of them that no one has ever heard before. Whether that’s a sound worth hearing again is a matter of taste, but when everything clicks, it can be legendary.

That sound can happen instantly, almost by accident, or it can take years of exploration. As Omar Rodriguez-Lopez, guitarist for the Mars Volta, will tell you, curiosity does have its payoffs. “I remember when I got my first delay pedal,” he says. “I’ve always used pedals to hide my playing, and now as I’ve been able to evolve as a player, I can remember that the thing I loved most about the delay pedal was that I could use a certain time setting, and it sounded like I was playing way more than I was. It made me want to learn how to play the way the delay sounded. The pedal itself pushed me to learn more about my instrument. I always liked this idea and this part of the process. It’s about learning from your gear, and learning from these little metal boxes that supposedly have no life and no influence, you know?”

There are countless examples of inventive players who’ve redefined how we hear music and guitar because of the unique way they’ve absolutely owned a specific effect pedal. It would be impossible to try to list them all, but here we’ve chosen what we believe are the 10 most historically significant instances of intrepid players who pushed a specific stompbox to its limits and changed the world as we know it.

An example of a first-run FZ-1A Fuzz-Tone. Photos courtesy of Simon Murphy

1. Keith Richards' Gibson Maestro FZ-1A Fuzz-Tone

“I’ve only ever used foot pedals twice,” Keith Richards wrote in Life, his 2010 autobiography. As it turned out, one of those occasions happened to be the recording of the Rolling Stones’ signature hit “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”—one of the earliest, if not the first, uses of fuzz in modern rock. Richards’ guitar line was supposed to be a scratch track for a horn section, “so I could give a shape to what the horns were supposed to do. But the fuzz tone had never been heard before anywhere, and that’s the sound that caught everybody’s imagination.”

Nashville studio engineer Glen Snoddy had stumbled onto the original fuzz sound in 1960, when an overloaded transformer shorted-out in one of the Langevin tube modules he was using to record an electric 6-string “tic-tac” bass. He designed a transistorized version of the effect and sold it to Gibson in 1962. “At first I was mortified,” Richards says, describing how he felt when he happened to hear “Satisfaction” blaring over a radio station in Minnesota. “We didn’t even know Andrew [Loog Oldham, the Stones’ manager] had put the [expletive] thing out! [But it was] the record of the summer of ’65, so I’m not arguing.”

YouTube It

An original 1967 Arbiter Fuzz Face. Photo courtesy of Starman1984

2. Jimi Hendrix's Arbiter Fuzz Face

As Frank Zappa told readers of Life magazine’s “The New Rock” issue in June 1968, the only way aspiring guitarists could even hope to sound like Jimi Hendrix was to “buy a Fender Stratocaster, an Arbiter Fuzz Face, a Vox wah-wah pedal, and four Marshall amplifiers”—and even then, of course, nothing was guaranteed. Shaped like the round, cast-iron base of a microphone stand, the Fuzz Face was a simple and durable unit that delivered gain and distortion with a vengeance. It was produced by Arbiter Electronics in London and went to market in the fall of ’66—perfect timing for Hendrix, who had just arrived in England and was wide open to trying the latest gadgets, no matter how experimental (as Roger Mayer, inventor of the famed Octavia pedal, found out when the two met the following spring).

“Love or Confusion,” from the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s debut Are You Experienced, is the first recorded instance of his use of the Fuzz Face, but the best example on the album is probably “I Don’t Live Today,” where the lower reaches of his tone actually start to break apart into shards of pure, controlled noise, years before anyone even thought to overdrive a guitar to such extremes.

YouTube It

A pristine specimen of a circa-’66 Sola Sound Tone Bender Mk II. Photo courtesy of Macari’s Musical Instruments

3. Jimmy Pages Sola Sound Tone Bender MK II

In the 2009 documentary It Might Get Loud, Jimmy Page remembers telling Roger Mayer that he was looking to get more sustain out of his guitar, so Mayer went off and invented the Tone Bender. The only thing is, it was actually engineer Gary Hurst who designed the little wedge-shaped box in 1965 (it was almost 50 years ago—so we can give the former Yardbird and Zep man a break!). Hurst licensed his creation to Sola Sound in London, and pretty soon blues-rock bands all over England were getting a deep, juicy sustain out of their solos. As Page told the local fanzine Hit Parader in 1968 (shortly before he founded Led Zeppelin), “I get 75 percent of my sound with [the Tone Bender]. It’s very similar to a fuzz box, but I can sustain notes for several minutes if I want to.”

Page’s guitar on the first Zep album seems to cook from the inside out with a signature Tone Bender sound (speculation says the MK II model), most notably on “Dazed and Confused” and “You Shook Me.” The unit’s appearances became less obvious on subsequent Zep recordings, but its association with Page was etched in stone. “It was this phenomenal thing,” he marvels in It Might Get Loud, “a distortion pedal that could make the guitar sound pretty rude.”

YouTube It

A clean example of a Vox King wah with a TDK 5103 inductor. Photo courtesy of Guitar Center Vintage Collection

4. Curtis Mayfield and Craig Mullen's VOX King Wah

Even in the late ’60s, when the wah pedal was primarily a blues-rock staple, it was almost inevitable that it would become synonymous with soul music. A well-placed wah could transform even a mundane, two-note riff into a plaintive wail, and that was all it took to draw artists like Curtis Mayfield to its expressive power. Surprisingly though, he preferred the simplicity of an auto-wah, as Craig McMullen, Mayfield’s go-to guitarist and originator of the “Superfly” wah guitar sound, explains: “Curtis never was too much for fooling with the gadgetry, which is cool because he had his own unique sound in the way he played, anyway. So all the wah-wah variations that you hear on those early records, that was me on the Vox.”

What often gets lost in the towering shadow of 1972’s classic Superfly is that Mayfield and McMullen had already etched the wah-wah into the soul-funk firmament the previous year with the sizzling double LP Curtis/Live!. Incredibly, this was the 5-piece band’s first gig together and it remains one of the grittiest, funkiest live performances ever documented. “You figure we’re at least going to do a couple of gigs to get tight,” McMullen quips, “but we were going to go for the jugular vein right now. And I was, like, ‘Okay, well—you lead, and we’ll follow!’”

YouTube It

A mint-condition Mu-Tron III. Photo courtesy of LosAngelesGuitarShop.com

5. Bootsy Collins' Musitronics Mu-Tron III

Designed by electronics whiz Mike Beigel, the Mu-Tron III debuted in 1972, but with its watery, wavy-sounding sweep, it really belonged in the psychedelic ’60s. Stevie Wonder used it on the Clavinet for his 1973 hit “Higher Ground,” catapulting it to prominence among gear freaks, including Bootsy Collins, who had just joined Parliament-Funkadelic and, at the ripe age of 21, was looking to redefine funk bass for a new generation. He took to the Mu-Tron like it had been custom-designed for him (years later, he adopted the “Boot-Tron” and “Zillatron” aliases in tribute), often using it in tandem with a Big Muff or a Morley Fuzz Wah for distortion.

“I’d Rather Be With You,” from his 1976 breakthrough, Stretchin’ Out in Bootsy’s Rubber Band, exemplifies Bootsy’s fascination with the dynamics of auto-wah and envelope effects, and how just a whiff of distortion could transform the bass into a lead instrument. Jimi Hendrix exerted a huge influence on Collins, and nowhere is this more dramatic than on the steamy bedroom classic “What’s a Telephone Bill?” (from 1978’s Ahh…the Name Is Bootsy, Baby!), which opens with a prolonged, light-fingered teasing of the Mu-Tron’s envelope filter and builds to a climactic solo drenched in distortion, wah, and Echoplex.

YouTube It

An early-’70s script-logo Phase 90. Photo by Larry Kent

6. Eddie Van Halen's MXR Phase 90

Whole volumes have been written about how Eddie Van Halen achieved his archetypal “brown sound,” probably because he pretty much demolished the way lead guitar would ever be heard again in a hard-rock setting. Beyond his stupefying technique, it was the brash, hyper-articulated and subtly phased distortion on early Van Halen songs like “Eruption” and “Jamie’s Cryin’” that really changed the game. Amazingly, EVH relied on a combination of pure amplification and voltage reduction—no overdrive pedals—to get his basic distortion tone, using an Ohmite Variac variable transformer so his Marshall Super Lead would run more efficiently at loud volume.

Eddie onstage in 1980 with a Phase 90 in the center of his meager pedalboard. Photo by Neil Zlozower/atlasicons.com

At the heart of his pedal setup, which he connected after the amp via a dummy load box, was an Echoplex EP-3, an MXR Flanger, and the vital MXR Phase 90. Also known as the “little orange box,” the Phase 90 had launched the MXR brand in 1972 and was popular for its simplicity: one knob, labeled “speed,” was all you needed to approach a decent (and inexpensive) simulation of a rotating Leslie speaker. EVH maintained that the unit, set at slow sweep, actually didn’t phase too strongly, and gave his tone a treble boost so his solos could cut through more easily. When your drummer is the heavy-hitting Alex Van Halen, you need every advantage you can get.

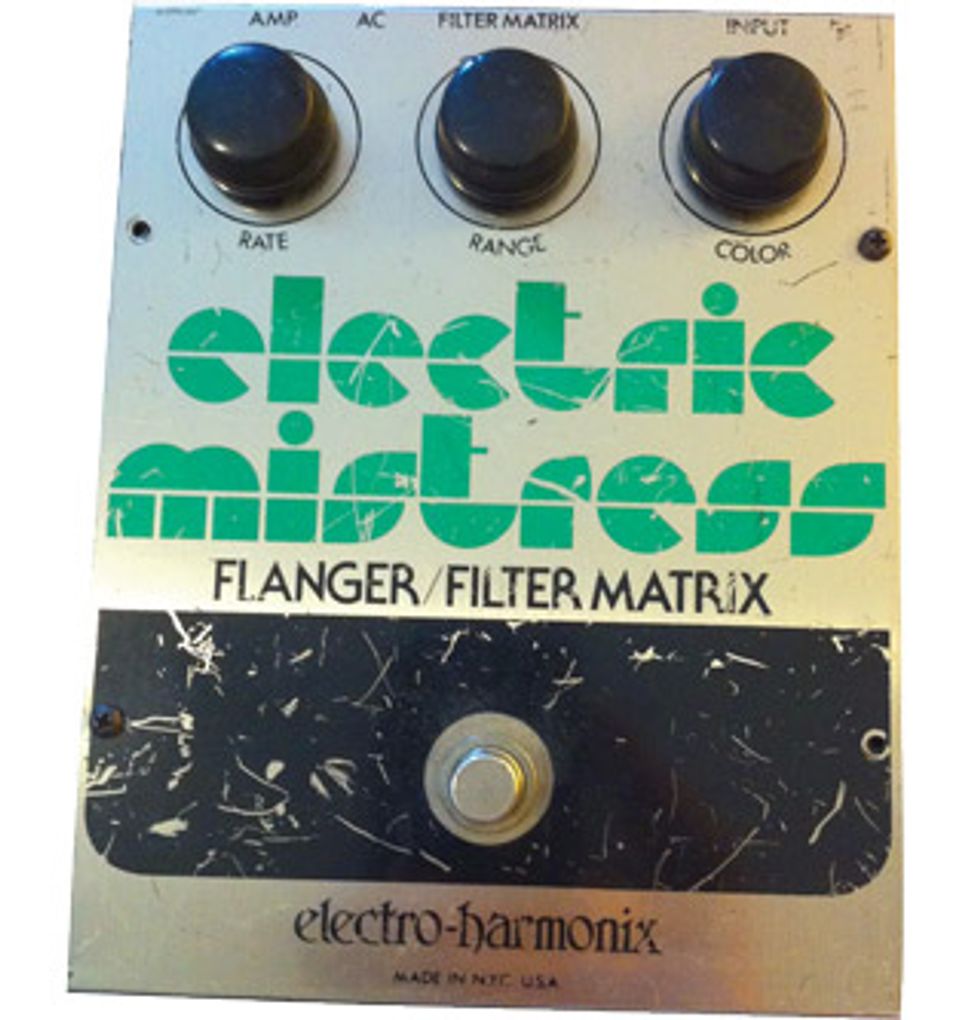

A well-used, late-’70s Electric Mistress. Photo courtesy of Alfi e’s Musical Instruments, Brighton, UK

7. Andy Summers' Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistress Flanger

One thing Andy Summers picked up during his brief stint in 1968 with prog-rock progenitors the Soft Machine came, ironically, not from the band itself, but the act they were touring with—the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Put simply, Summers was “enthralled,” and although he never cites Hendrix as a direct influence, there’s a definite sense of the shamanistic that permeates the Brit guitarist’s work with the Police.

Summers onstage in 1982. Photo by Neil Zlozower

It started with a Maestro Echoplex EP-3 he acquired in late ’78, just as the band’s Outlandos d’Amour was leaking onto the airwaves, and evolved into a deep fascination with a wide range of phasers, flangers, and guitar synthesizers. The Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistress is probably the most recognizable of anything in the Summers arsenal. Incorporated into a pedalboard custom-designed by effects legend Pete Cornish, the unit gives “Walking on the Moon” its otherworldy textural quality, and is one of the stars of the band’s third album, Zenyattà Mondatta, particularly on “Driven to Tears” and the upbeat hit “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da.”

A rusted-but-rocking original Deluxe Memory Man. Photo courtesy of JHS Pedals

8. The Edge's Electro-Harmonix Memory Man Deluxe

Knowing when not to play is probably the instinct that saved the Edge a lot of headaches in the early days of U2, because it opened him up to the possibilities of using manipulated sound to further his ideas. Lucky for us, he was polishing his deceptively simple guitar technique during a time—the late ’70s and early ’80s—when new and exotic effects pedals were flooding the market. The Electro-Harmonix Memory Man Deluxe was one of these. It improved on the Memory Man (originally released in ’76) by adding level and chorus-vibrato to the existing delay, feedback, and blend controls, which made for a box that could churn out alien tone bends and echo washed delays seemingly without limit.

“I got this echo unit and I brought it back to rehearsal,” Edge recalls in It Might Get Loud. “I just got totally into listening to the return echo, filling in notes that I’m not playing, like two guitar players rather than one—the exact same thing, but just a little bit off to one side. I could see ways to use it that had never been used. Suddenly everything changed.” The changes came fast and furious. You can hear the Memory Man prominently on “A Day Without Me,” the lead single from U2’s Boy, and for the next decade the Edge honed a richly layered and mutable sound that guitarists young and old are still trying to duplicate.

YouTube It

A circa-’82 original TS9 Tube Screamer. Photo courtesy of Ibanez

9. Stevie Ray Vaughan's Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer

Almost right out of the gate, Stevie Ray Vaughan was touted as the heir apparent to Hendrix—a challenge he took on with disarming reverence, even as it became clear he was mapping out a style all his own. Being steeped in Texas blues had a lot to do with it, but SRV was also a tireless tone hound, and when he sniffed out the first version of the Ibanez Tube Screamer (the TS808), he knew he’d found the midrange bite he’d been looking for. He soon moved on to the grittier TS9, which seemed to shimmer a bit more in the higher registers.

“I use it because of the tone knob,” he told Frank Joseph in 1983. “That way you can vary the distortion and tonal range. You can turn it on slightly to get a Guitar Slim tone, which is how I use it, or wide open so your guitar sounds like it should jump up and bite you.” SRV and Double Trouble’s Texas Flood sports a few notable examples, including the title track, the classic hit “Pride and Joy,” and the instrumental blues boogie “Testify”—all testament not only to his versatility as a player, but to his incomparable ear for crafting a lead tone that perfectly fit the mood of a song. By the time he got to 1984’s Couldn’t Stand the Weather, everyone knew an SRV solo when they heard it.

YouTube It

A mint-condition original WH-1 Whammy. Photo courtesy of DigiTech

10. Tom Morello's DigiTech WH-1 Whammy

When Rage Against the Machine’s self-titled debut exploded like a cluster bomb in 1992, the consensus wtf? moment among guitar heads came at about the 3:50 mark in the album’s lead-off single, “Killing in the Name.” Tom Morello’s impossibly elastic solo was the boldest use yet of DigiTech’s WH-1 Whammy pedal, introduced in 1989. The Ferrari-red unit featured pitch-bending and harmonizing technology developed by IVL Audio, and with its expression pedal allowed squeals and dive-bombs that could extend as low (or as high) as three octaves.

For Morello, the Whammy offered an intuitive way, especially in the higher octaves, to emulate the siren-like samples he heard in the southern California gangsta rap sound of Dr. Dre, DJ Quik, and Ice Cube. “I was basically designated to be the band’s DJ,” he said in a 2008 interview, “and I found, with very simple manipulations of a very simple pedal, that all of a sudden the guitar, for me, was finding a lot of very new sonic possibilities.” Morello tapped into the unit’s harmonizing capabilities as well, most notably on the devastatingly funky “Know Your Enemy,” which opens with an infectious stacked-fifths riff and culminates in one of the nuttiest guitar solos of the ’90s.

YouTube It