What makes a bass guitar perfect? Now that is a loaded question! We bassists seem to be in a constant search for the perfect instrument even if we already own several instruments we consider to be “great.” Quite a few players are well known for playing one instrument throughout their careers, or at least through their commercially successful years. In many cases, these players made small tweaks to their instruments, and in the process created their perfect bass—or at least a version of it.

Some of these players ended up having companies reproduce those instruments as signature models. Billy Sheehan is a great example. Back in the day, he installed a Gibson humbucker right by the neck on his old P bass (called “the Wife”) to get the sub-lows of an old short-scale bass, and scalloped the upper frets to facilitate bending after seeing Yngwie Malmsteen do it to his guitars. Billy also used two outputs to amplify, process, and compress each pickup independently. These are features that no other instrument could offer at the time and were essential in achieving his signature sound and facilitating his playing style. Modifications and replacements were necessary.

On the other hand, many bass legends play a stock instrument. I have quite a few friends and colleagues, however, who find an instrument they fall in love with, take it home, and then start changing everything. This behavior puzzles me slightly, because I’m a firm believer that every single ingredient in the soup contributes to the flavor. I’m not saying having an inquisitive mind and searching for improvement is a bad thing at all, but sometimes it really isn’t necessary.

One of my current favorite instruments is a 2015 Squier Precision I bought brand-new for about $250. The day I purchased it, I had spent two hours playing 15 or so P-style basses in the same store, through the same amp, and at roughly the same volume. The instruments ranged in price from $250 all the way to $5,000. I went through my regular mental checklist of searching for dead spots and making sure the string-to-string volume consistency was good, determining if the weight was well distributed with no neck dive, making sure the brightness and sustain were even, and inspecting the oil or lacquer on the back of the neck for playability and quality. The winner was the Squier and I thought to myself, I must be wrong. (You’d understand why if you were in the store with me looking at the P-bass-style options with very impressive builder names and logos on the headstocks.) So I repeated the entire process, arrived at the same conclusion, and purchased the Squier.

it really isn’t necessary.

Once home, I thought to myself that the bass must have cost about $100 to make at the most, but probably more like $75. I figured the pickups and bridge were likely $5 parts and that there was no way I could just play the bass as is. But that’s when I had an epiphany: I purchased the bass because I loved the way it sounded! Just because logic and experience tells me I should be able to make the bass sound better with modifications and replacement parts doesn’t mean I should. And it certainly didn’t mean I had to.

I took the bass to some Nashville recording sessions and gigs following the purchase. Two engineers—who heard the bass before they saw it—asked me what year it was from, remarking it was the best-sounding vintage P they had heard in a while. They were both surprised and embarrassed when I told them it was a 2015 Indonesia-made Squier. These people make a living with their ears, so it was a nice reaffirmation that I wasn’t crazy for choosing it over the basses that looked the same, yet cost thousands more. Don’t get me wrong: You do get what you pay for in many areas. This P’s frets needed smoothing out and the instrument itself doesn’t feel expensive or well built. I don’t get the sensation of driving a high-performance car when playing it, but the sound is astounding.

Sometimes the magical parts are already installed by a builder, but they have to come alive or be awakened, rather than be replaced. For instance, I have a custom 5-string bass I ordered with all my special preferences. When it arrived, I loved everything about it, except the sustain was slightly shorter than other same-brand basses I own and the 5th string was not quite bright enough. To remedy this, I had planned to switch to a different nut and potentially change the bridge. Well, fast-forward two years to just last month, when, after several nights in a very cold truck, the lacquer on the fretboard had completely come apart. To my surprise, the tone changed by opening up beautifully and the two issues I was planning to spend time and money on were effectively fixed.

I see a lot of the same guys selling basses they have modified—heavily in some cases—when I’m checking out online bass forums. It seems like it’s a pattern: They fall in love with a bass and then try to change it. We all know (or should know) that doesn’t work with humans. If you fall in love with somebody, you also fall in love with his or her quirks. Plastic surgery is not always the best option.

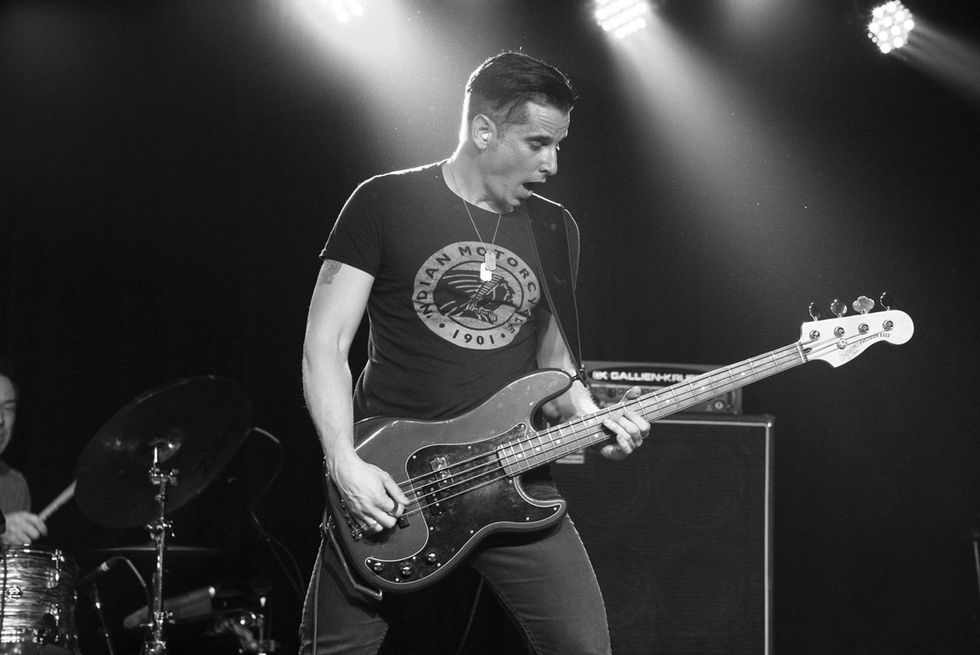

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig