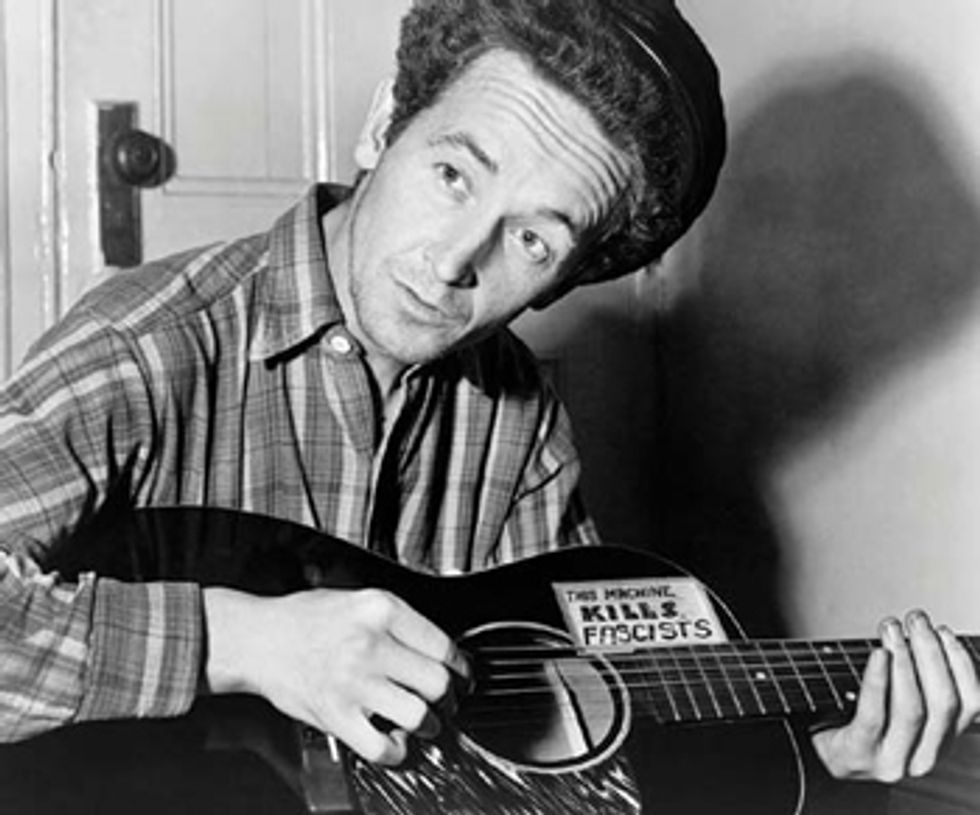

Woody Guthrie in 1943 with his famous “This Machine Kills Fascists” flattop—a ’40s Gibson Southern Jumbo. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

As much as we’d all like to think our instrument choices are based only on the quest for tone or playability, it often comes down to style. My career as a guitar tailor to the stars has taught me that even platinum-selling artists check the mental mirror when making instrument choices. In fact, the visual appeal of a guitar has figured so heavily in my experience, I’m surprised that guitar shops don’t have those multipanel mirrors found in clothing stores. I can see it now: “Does this guitar make me look fat?”

It has reached the point where it’s no longer unusual for new guitars to be conceived from scratch for individual expression—not to mention the abundant aftermarket options for individualization out there. The trend is even evident at traditional factorybuild guitar companies, with many converting to “we’ll build it your way” salad-bar shops.

Of course, guitar personalization goes way back. Woody Guthrie’s flattopped billboard declared war on fascism, and Merle Travis’ business card was emblazoned on his guitar’s body and fretboard, long before Eddie Van Halen bought his first roll of masking tape. There was a period in the late 1960s when it was de rigueur to paint your guitar with fluorescent paint in some sort of psychedelic motif.

As I mentioned in a previous column, the 1970s required rockers to Zip-Strip their instruments’ finish down to an earthy, natural look. This was probably a direct reaction to the flashy and “old-fashioned” appearance of country or surf bands that adopted the bright, custom colors. The trend seemed to last until the end of the decade, when the painted and pointy guitars started their slow march into the mainstream. And this brings us back to Mr. Van Halen. It may have been his tapping and whammy bar revolution that awed guitarists at the time, but in the long-term, the DIY paint job and aftermarket customization could be Edward’s most enduring contribution to the guitar industry.

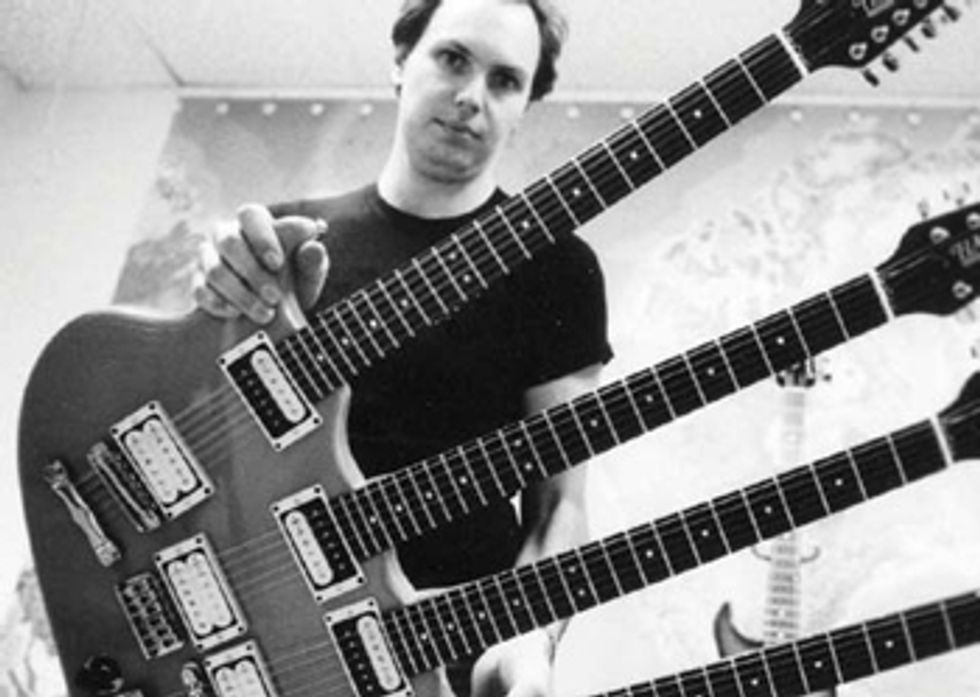

The author with the 5-neck Hamer he built for Cheap Trick’s Rick Nielsen circa 1980.

As the ’80s got started, the ante was upped. I remember examining Ace Frehley’s crazy array of guitars backstage while working with Kiss. It was a revelation—guitars with smoke bombs and sequencing marquee lights that truly were stage props. The 1980s were prolific times for instruments doing double-duty as fashion accessories. I know, because I was right there in the middle of it all. It was fun and frivolous, and just about any crazy idea was worth exploring. Airbrushed graphics, metal studs, builtin- ray-gun sound effects, and LED lights—it seemed like everyone had caught up to Kiss. Yes, there were cool and useful guitar designs that didn’t rely on their looks to get by. Some of my favorite guitars are from this era, with the Jackson Soloist being one of them, and I think they still stand up today. The era actually set the stage for the marketplace, as we know it now.

Personalization trends that companies or guitarists create, follow, and chase have been good for the industry—it keeps the grease on the griddle. Guitar styling, as I like to call the exercise of making a guitar look a certain way, is at an all-time high. There was a time when stylists could satisfy their job requirement just by changing out a few pieces of hardware. Now, the customer enjoys complete control over the color, shape, electronics, and tonewoods. It is certainly the era of personalization in all things visual with musicians being able to create their own mix through a vast array of sample-and-paste options.

Still, it is hard to imagine a roots-rocker testifying on a shred guitar, especially if it had a leopard finish. It comes down to the appropriate style, and that’s where the mirror comes in handy. For me, I like the idea of breaking the rules in some subtle way. I had a conversation with one of my favorite artists about how completely whack it would be for him to step onstage with a traditionally styled, semi-hollowbody guitar, that still did his shred-style bidding. I wasn’t trying to reinvent his persona, but I liked the idea of smashing the expectations of the audience. Ultimately, he didn’t go for it—just not his style I guess. If only I’d had that mirror handy.

Jol Dantzig is a

noted designer, builder,

and player who co-founded

Hamer Guitars,

one of the first boutique

guitar brands, in 1973.

Today, as the director of

Dantzig Guitar Design, he continues to

help define the art of custom guitar. To

learn more, visit guitardesigner.com.

Jol Dantzig is a

noted designer, builder,

and player who co-founded

Hamer Guitars,

one of the first boutique

guitar brands, in 1973.

Today, as the director of

Dantzig Guitar Design, he continues to

help define the art of custom guitar. To

learn more, visit guitardesigner.com.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)