Nestled in the South Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn is Barbés, a quaint performance space that brings a little bit of Paris into the concrete jungle. Owned by two French musicians, Barbés is part listening room, part art film mecca, and the general community center for the area’s artists and musicians. On most Sundays, if you wander into the back room, you can find one of the city’s best-kept musical secrets. Guitarist Stephane Wrembel holds court during this weekly gig and not only pushes the boundaries of what is considered Gypsy jazz, but gathers influences ranging from Greek and North African music to Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd into an entrancing, yet accessible style.

After graduating from Berklee, Wrembel planted himself in Brooklyn among a healthy community of musicians, artists, and other creative types that bolstered and inspired his muse. Unlike many of his derivative contemporaries, Wrembel pushed the ghost of Django Reinhardt aside when making his latest album, Origins—a collection of fresh and sometimes cinematic acoustic tunes full of precise picking and hummable melodies.

Wrembel’s music caught the ear of Woody Allen (who happens to have a deep love for all things Gypsy jazz), which led to Wrembel’s composition, “Big Brother,” being chosen for the soundtrack to Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona. That partnership continued, and soon after, Allen asked Wrembel to write the theme for Midnight in Paris, which Wrembel performed at the 2012 Academy Awards. It was quite a break for the DIY musician, who reflects on his big year by sharing with us his affinity for stargazing, his compositional style, and why he views the Django community as one big competition.

Tell me about your childhood

in France. When did you first

pick up the guitar?

First, I was playing the

piano. I’m originally from

Fontainebleau–which is the

home of Impressionism. I

studied piano at age 4 and

was classically trained in the

Impressionist style by an

old piano teacher who knew

Debussy, so I was trained in

that old traditional school. I

started playing guitar when I

was 15 and I was playing more

’70s rock like Pink Floyd and

Zeppelin. When I was about

19 or 20 I really wanted to

expand my horizons so I practiced

Django stuff, jazz, Indian

music, African music, and stuff

like that.

Did your parents push you

into music?

I have two sisters, and my mom

really wanted us to play an

instrument. We started with the

piano because that is what she

knew. She wanted us to continue

with an instrument and

when I was 15 I said, “I really

wanted to play the guitar.”

When I was a teenager I really

loved David Gilmour—he is

still my favorite—Frank Zappa,

Jimi Hendrix, and Jimmy Page.

Loved Andy Summers, too.

So Django wasn’t one of your

primary influences when you

were younger?

Django’s music has always been

around, especially because I am

from the area where he settled.

For us, it was just traditional

music, much like bluegrass is

here. It’s always been there but I

never really paid attention to it.

It was only when I studied jazz

and French traditional music that

I really started to discover him.

Did you move to the States

specifically to study music?

I have been fascinated with

the United States since I was a

kid. I always wanted to move

here. It was a childhood dream.

Being a musician, going to

Berklee was another dream

from when I was a teenager.

When I was 26 I got a scholarship

and was able to go get my

tutorings. I concentrated mostly

on jazz and all kinds of world

music. I studied Indian music

there, Western African music,

and Greek music a little bit.

What was it that most interested

you in those types of music?

To me, music is only one

thing—it’s just music.

Different countries approach

the language from different

directions, but they all melt

together at the end. Indian

music is very good for studying

the architecture of rhythm;

you understand rhythm way

better with Indian music. And

their ways of practicing are

amazing. With African music,

they have an amazing rhythm

and the way they use certain

colors of percussion, I can

do on guitar. The jazz music

is very important because it

makes you a more confident

improviser over complicated

chord progressions.

When did you make a choice to

focus more on acoustic music?

I don’t really focus on acoustic

music, it has just been added

to my playing. It was only

really when I discovered Django

that I learned to play acoustic

instruments. If you give me an

electric guitar, I can play like a

real electric guitar player, you

know? It’s just been added to

my arsenal of techniques. I find

more power in the acoustic

instrument than the electric

instrument. It’s also because

that is what’s happening [with

me] now. I also use electric

sometimes, although I haven’t

recorded with it yet but I have

projects for that.

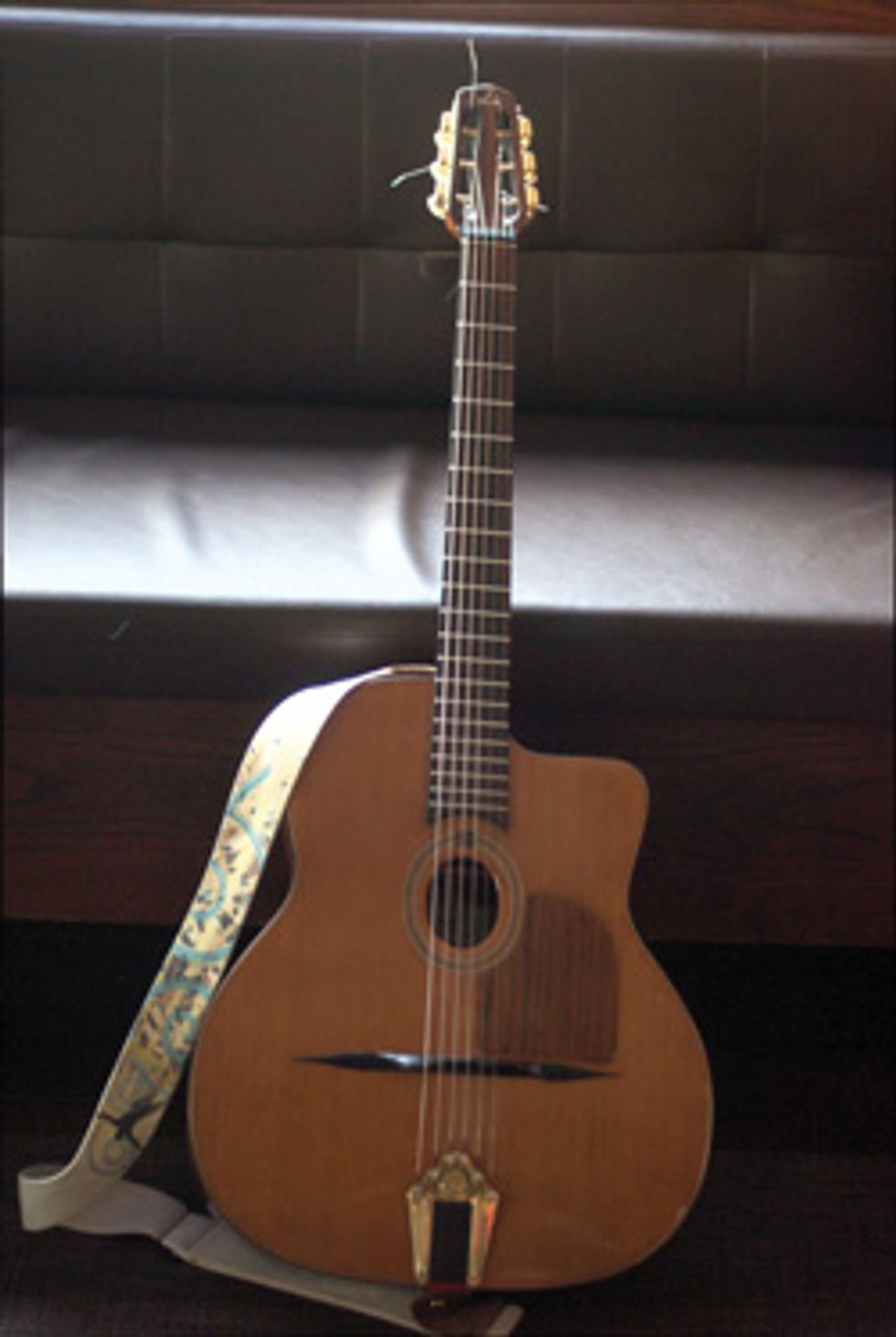

When Luthier Bob Holo first met Stephane Wrembel, the idea of creating a guitar for the picker hadn’t crossed his mind. But then the two spent a night talking about tone and inspiration. “That guitar wouldn’t exist without guys like Stephane. I met Stephane, Adrien Moignard, Mathieu Chatelain, and Gonzalo Bergara at a festival in Boston in the mid- 2000s and it really seemed as if they were starting a rebirth of this music in a ‘new school,’ so to speak,” remembers holo. due to this original approach, holo decided to create the “nouveau” model, while also taking some of Wrembel’s advice to heart.

He was moving more and more toward the acoustic side and we had a long talk one night,” Holo explains. “he told me, ‘Bob, don’t live in the shadow of Django, live in the light of Django. He would want it that way.’ It’s easy to forget that with the familiarity of his music these days and the postbop/ acid/atonal jazz that has come since, but back when Django was playing his music, it was way out there.” The idea stuck with Holo, who was deep into studying the guitars of some of the early master builders.

After analyzing some of the builders who moved from Italy to France in the 1930s— such as Busato, Dimauro, and Bucolo—Holo learned that they had taken inspiration from romantic guitar builders from the previous century. “They cut their teeth in Italy building budget guitars for various companies and then they came to France to build their names, inspired by political freedom and the birth of jazz,” says Holo.

Holo was not only looking at the established masters of the craft for guidance, he also talked with many young artists to see what they seek in a Gypsy-style guitar. “as I talked with these incredible guitarists, they’d always say something like, ‘oh Bob, I played this [vintage maker] and it was so beautiful. It had this [element of tone] and it had that [characteristic of attack or decay] and I was in love, but it was just so hard to play and in the end I’m not sure that the tone would fully translate to modern work.’ Throughout all of this I kept hearing Stephane’s voice: ‘Light of Django ... innovate.’”

The finished version of Wrembel’s nouveau sports a western red cedar top with the back and sides containing a layered mixture of honduran rosewood, walnut, and mahogany. Holo went with a 670 mm scale length and stuck with the honduran rosewood for the fretboard. The guitar was set up with Argentine Savarez .010 strings, but just like Django, he switches out the first string for a .011.

With a background in sound and design, Holo began the journey to understand why these old guitars sounded like they did. He also wanted to incorporate the ideas that modern players were asking for. “I kept building and taking them to festivals and getting feedback,” says Holo. “One year I asked Mathieu Chatelain for his feedback and he said, ‘here’s my feedback: how much do you want for it?’ My jaw must have dropped because he started laughing and said, ‘You should have seen the look on your face just then, but I’m totally serious. How much?’”

Holo opened shop in the Pacific Northwest soon after, and new-school Gypsy players began knocking down his door. “It has been a real-life epiphany working with them to give them the kind of tool they want. It’s incredibly gratifying work.” For more information on Holo’s guitars, visit hologuitar.com.

Wrembel plays his Holo Nouveau at the intimate Empire Hotel Rooftop in NYC on June 18, 2012. Photo by Scott Bernstein

What type of projects?

You would be surprised. It’s

really the same thing. That one

style, whether I play electric or

acoustic, it doesn’t really change

much because I play the acoustic

really like an electric player.

But with the acoustic technique

I give out as much power as,

say, a Les Paul through an amp

with distortion.

Do you feel that your technical

approach changes when moving

from acoustic to electric?

It doesn’t really change because

once your technique gets better

you have ways to make the guitar

ring in a very different way.

You can use the sympathetic

ringing of the guitar, which is a

type of control that’s a bit more

advanced. That is something I

couldn’t do before so even when

I am playing a distorted guitar,

I use the sympathetic vibration

of the other strings and it makes

the sound bigger.

Do you use a Django-style

picking technique?

It was completely inspired by

Django and playing the oud.

Can you explain how that

style works?

It’s not only the right hand but

also the left hand. The right

hand doesn’t exist all by itself.

You can’t really talk about one

without the other. Basically,

the thing is you have to press

hard with the left hand on the

strings—that’s very important.

You have to make sure to put

the two hands really together,

which is surprising to say that

but most people don’t. It’s very

hard to have two hands play

well together. There are all

kinds of things. Like you don’t

touch the strings because you

want them to resonate in sympathy

with the rest to create a

natural reverb.

Do you follow a strict alternate

picking technique?

Usually when you change

strings you use a downstroke

as much as possible and you

use more downstrokes than

upstrokes. There’s no real rule.

It’s not as precise as that. It’s

like when you drive. When you

learn to drive, you put your

hands on the wheel and learn

everything internally. After that

you are able to drink a coffee

and drive, so the rule becomes

“drive.” It’s the same thing with

the guitar.

For your latest album, did you

compose specifically for this

project or were these tunes

laying around for a while?

Almost all of the material was

written for this album. “Bistro

Fada” was the song I wrote

for the Woody Allen movie

Midnight in Paris. I remade a

new version for this album,

for sonic reasons and to match

the color of this album. There

is also “Water is Life,” which

was written for my first album

in 2005, but it was a classical

guitar and bass version. We

recorded it more like how we

perform it live with the drums.

Otherwise, everything else was

written for this album.

Speaking of Woody Allen,

how did he approach you to

create the theme for Midnight

in Paris?

The first time he used one of

my songs on his movie [Vicky

Cristina Barcelona], and the second

time his producer called me

and asked if I could compose a

theme for the movie that would

represent the magic of Paris.

Woody tours with his own

band all over the world. Did

you ever get a chance to play

with him?

Nah, I’ve actually never met

him. We talk through his

producer. Once it’s time for

pre-production he is already

onto his next movie or some

other thing. It’s not like we have

time to hang out. Busy guy.

When you are presented with

a compositional “assignment,”

like writing a score, how do

you approach it? Is your process

any different?

Actually, I go blank and move

into a trance state. It just happens.

When it’s time to compose

I get in that mood and it lasts

for a few days and since I can’t

score ideas in my head I throw

the ideas into GarageBand. I

then go back and refine them

and it becomes more architectural

work. For me, it’s very

important to have a mood and

a musical idea. That’s the first

thing. After that, I rework it.

Do your ideas usually begin

with a melody or a chord

progression?

It’s all entangled. Once I have a

rough idea I spend a few hours

to really play around with it—

change chords, move the bridge

around—so many choices. I

usually do that on the spot right

after composing a song.

The track “Tsunami” really

shows the orchestrated, more

scenic influence of movie

scores. What composers do

you listen to for inspiration?

I listen to movie scores a lot.

I listened to a few scores from

Hans Zimmer and I have

checked out the classic ones like

Jaws [John Williams]. A score

that I really love is the one from

Pi [Clint Mansell], and I am

also a big fan of Howard Shore

[Lord of the Rings, Hugo].

This image shows a structural light test of a Bob Holo Hotclub model. Notice the smaller braces used to help support the bridge. Photo courtesy of Bob Holo

What is it about those scores

that draws you in?

I can’t tell you. I have no idea.

There is just something about it.

You know, there is just so much

you can’t explain about music. I

don’t go too far as to say I like a

certain kind of harmony because

it’s beyond that. When you listen

to music, either something

touches you or it doesn’t. It’s not

because of the notes, the notes are

the same. It’s just something else.

Do you have aspirations

to do more movie and

soundtrack work?

As of now, people know me and

have asked me to score their

film. I don’t really have much of

a clue as to how it comes about.

There are agents that do some of

that stuff, but I don’t really have

an agent right now. It’s a tough

book to open. Usually, when

[directors] have a movie, they

want to work with someone

they already know who will do

a certain kind of score. They fall

into this security. That’s the reason

why the whole film scoring

industry is held by like, I don’t

know, 20 composers. There are

not many composers who have

access to bigger movies.

On “Voyager” you pay tribute

to what could be considered

an unlikely influence: astronomer

and author, Carl Sagan.

He translates to us the wonders

of the universe. In his books and

everything, I just think he has a

way of saying things that are so

brilliant at explaining how the

universe works. Thinking about

Voyager 1, that’s his mind. That

thing is traveling through space

right now. It’s like a mind warp.

If it hadn’t been for him, we

wouldn’t have pictures of Saturn

and Uranus. We wouldn’t have

pictures of any of the moons.

Nowadays, humanity is more concerned

about economies for themselves,

like just making money

and cheap labor instead of looking

to the stars. It just makes me

dream to think about the stars.

Was the album recorded live

in the studio?

We recorded live in the same

room without headphones. Just

live. Like really live.

How did you mic up the guitar?

I have no clue. That’s a question

for my producer. I have a few

things in my home studio, so I

know how to record my guitar

and stuff. I think he had two or

three mics.

Tell me about the guitar you

used on this album.

I used a Bob Holo Nouveau

model with a cedar top. [For

more information on Wrembel’s

guitar, read “Bob Holo on

Stephane Wrembel’s Nouveau

Guitar” on pg. 134]

What type of strings and picks

do you use?

I use D’Addario strings and a

Wegen pick.

Do you use the really thick ones?

It’s a little bit thick but not like

those huge things.

Like a 2 mm?

Yeah, I don’t even really know

the size. I recognize them

online, click on the photo, and

then buy them.

Even though your music has

its roots in Django’s music,

you are pushing beyond playing

jazz standards. Do you

feel connected to Django’s

legacy or is he just one of

your influences?

The Django community,

whatever that is, is a big competition.

It’s like, “Can I play

the new lead faster than you?”

I have no clue what is going

on with all these guys—I just

like to play my music and

compose. You can hear the

influence of Django and I love

to play the acoustic guitar.

I found a good sound with

that by mixing it up with the

drums, but I don’t try to play

like Django. I am more influenced

by Pink Floyd than anything

else. My music doesn’t

really belong to any genre.

Stephane Wrembel's Gear

Guitars:

Bob Holo “Nouveau” model with a 50-year-old

Western red cedar top and Honduran rosewood/

walnut/mahogany back and sides, Gitane DG-340

Stephane Wrembel signature model (“I brought mine

in to be refretted, and I decided to leave it fretless!

So I can play it like an oud. I usually don’t play it

live—more in the studio.”)

Amps:

AER Compact 60

Strings:

D’Addario .010s with the top string changed to an .011.

You take a pretty DIY

approach to your career. What

do you have in mind for the

next album?

I am completely independent, I

don’t have a label or anything,

so I do everything myself. I put

one foot in front of the other.

Right now I am taking care of

touring behind this album, so

I would say for the rest of the

year I will tour and then I will

think about composing more. I

have a few ideas right now that

I am putting in the can, more

movie-like stuff.

Will it be in the same vein

of Origins?

I don’t know. Right now, while

I try to perform this album, I

can’t think of the next one yet.

I started to put bits of things

together, but I don’t have a definite

color yet.

gSpeaking of Pink Floyd, have

you had a chance to see Roger

Waters’ The Wall tour?

I’ve seen it 12 times—eight in

Europe and four in the States—

and I have a cool photo of him

and I because he came to see me

play last year. After that we went

out for dinner, it was really fun

and such a great experience.

YouTube It

Armed with his cedar-topped Bob

Holo Nouveau model, Wrembel

leads a quintet through “Tsunami,”

off his latest album. The band kicks

in at 2:57 as Wrembel effortlessly

unleashes some of his Djangoinspired

lines.

>

This 15-minute performance from

Wrembel’s weekly gig at Barbés

starts with some exploratory drones

but gives you an up close look at

his right-hand technique.

Fronting a trio with rhythm guitarist

Ryan Flaherty, Wrembel tackles two

of Django’s most famous compositions,

“Minor Blues” and “Swing 48.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)