Following World War II, Germany was a broken nation: divided and conquered and, understandably, something of a cultural desert. By the mid 1960s, while most of the world was swept up in a wave of liberation and rock 'n' roll, Germans were tapping their toes to schlager—a type of music that was über-square, inoffensive, sentimental, and the embodiment of everything un-hip. German youth—born during the war, coming of age, ashamed of their country's past, and aware they were missing out—were pining for something more.

And more was about to come.

Dubbed “krautrock" by a smitten but condescending British press, the new German sound fused electronic music and avant-garde sensibilities with psychedelic pop and ambient textures and soundscapes. Bands like Neu!, Faust, Kraftwerk, Harmonia, and Amon Düül II were prolific and influential. Their innovations were eventually adopted by A-list tastemakers like David Bowie, Brian Eno, and many others.

But every scene has its outliers, and krautrock's was Can.

Can was not like other German bands. For starters, their music grooved. It was danceable, funky, and hypnotic. But more importantly, Can's music was guitar-centric. True, they experimented with ring modulators, oscillators, tape editing, filters, minimalism, and weirdness—as was de rigueur for a German band of their era—but guitar was central to their sound. Guitar gave them their edge. It planted their flag firmly in the rock camp, although Irmin Schmidt, Can's keyboardist, isn't so certain. “Sometimes we weren't sure we made rock," he says. “We made contemporary classical music, in a way."

Can were based in Cologne (in what was then West Germany) and operated in something of a vacuum. They had their own studio—which changed locations a few times—and spent countless hours jamming, rehearsing, defining, and refining their sound. Their music was flexible, improvisatory, and open-ended, but their approach was disciplined and focused. Their golden period—at least according to many critics and fans—was in the early '70s, when Damo Suzuki was their lead singer. (Suzuki left Can in 1973.)

In addition to Schmidt, Can's core members were guitarist Michael Karoli, drummer Jaki Liebezeit, and bassist/technical expert Holger Czukay. That lineup also included, at various times, Suzuki, Malcolm Mooney (vocals), Rosko Gee (bass), and Rebop Kwaku Baah (percussion), among others.

Can didn't sell millions of albums or even tour the U.S.—at least not in their original incarnation, which broke up in 1979. But their influence is massive. For example, John Lydon (PiL) and Mark E. Smith (the Fall) cite them as an inspiration. Radiohead and Unknown Mortal Orchestra covered their songs. The band Spoon took its name from one of Can's singles. Kanye West sampled them. And Flea and John Frusciante (Red Hot Chili Peppers) flew to Germany to present them with an ECHO award (the German equivalent of a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award).

Our focus here is the guitars of Can. We spoke with Irmin Schmidt, Damo Suzuki, Rosko Gee (Czukay's replacement on bass in 1977), and a few others to paint a picture of this legendary and important band, and its approach to the instrument.

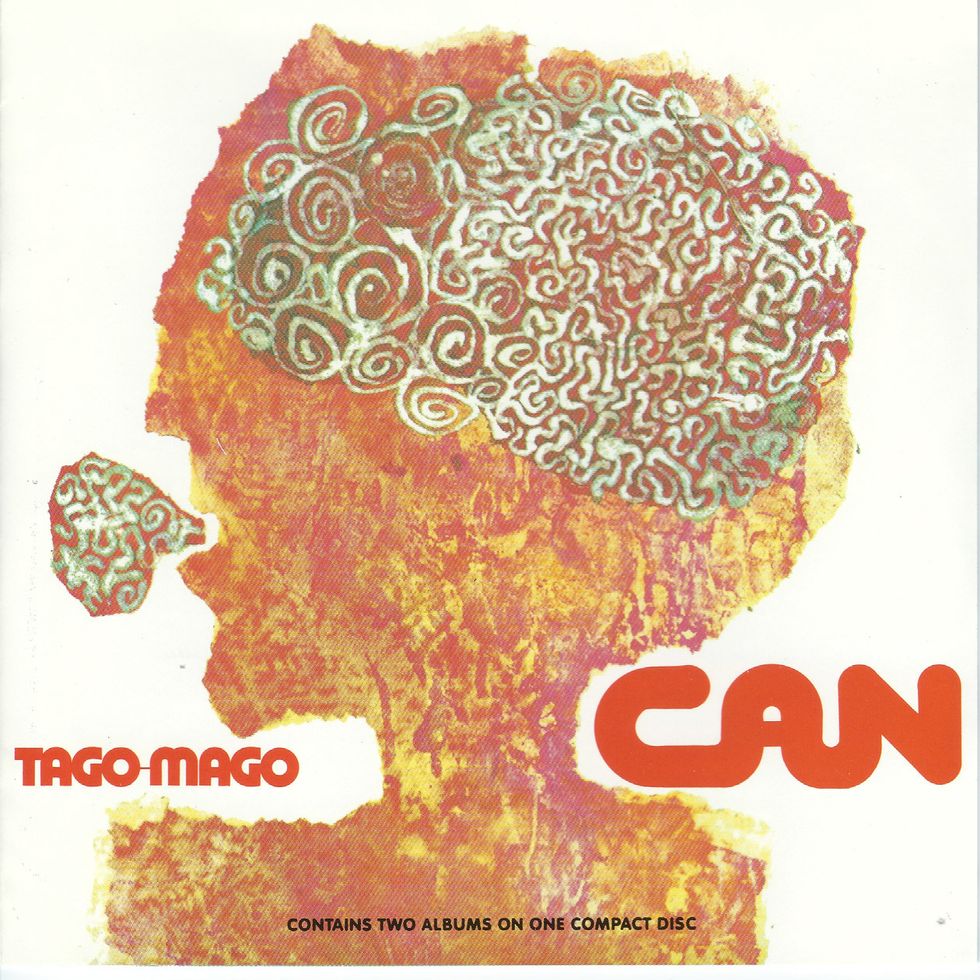

The 1971 double album Tago Mago is Can's studio pinnacle. It's a showcase for both Holger Czukay—on bass and performing studio tape manipulations—and guitarist Michael Karoli, and includes the 18-minute trance-funk marvel “Halleluwah."

Castle of Sound

Can started in 1968 as a loose band of acquaintances. Czukay and Schmidt met in Cologne, where both were students of electronic music pioneer, composer, and influential maverick Karlheinz Stockhausen. “We studied with Stockhausen and later we worked with him in the electronic studio, which was part of our studies," Schmidt says. “A lot of important composers and figures of the new music came along and gave lessons, but the main thing was Stockhausen—that was highly interesting and, of course, we learned a lot—although neither Holger nor me had the intention to make music like Stockhausen."

Karoli knew Czukay from Switzerland. Karoli was a student at an exclusive private high school and Czukay was his teacher—although those roles were reversed when it came to learning about rock 'n' roll. Both returned to Germany following Karoli's graduation and Czukay's dismissal. “[I was fired] for being too, er, intriguing," he told the U.K.'s Fact magazine in 2009. “But it was no problem."

Liebezeit was a local jazz head. He knew Schmidt, but was looking to do something different, which was what Can was about. “Jaki was a jazz musician," Schmidt says. “He was drumming through the whole jazz history—from the beginning to free jazz—but Can didn't have a one-dimensional aesthetic basis. It brought together classical and modern contemporary classics, electronics, jazz, and the influences from America."

Can's first gig was at an art exhibit in Schloss Nörvenich, a small castle in a town not far from Cologne. It was also the members' initial introduction. “We had never all met and had never practiced, but we played there for the first time," Czukay told Jason Gross, the editor of Perfect Sound Forever, in a 1997 interview. “That became somehow very exciting. Wild and sometimes unorganized, but at least exciting."

That excitement bore weird, wonderful fruit. From the beginning, Can's music was a groove-centric synthesis of everything 20th century. Stockhausen, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, cutting-edge tape manipulation, various kinds of world music—anything and everything worked. Those disparate influences formed the band's collective musical subconscious.

“We didn't try to incorporate anything into anything," Schmidt says. “Holger and I were students of Stockhausen. We were fascinated by what, at that time, were totally new possibilities to create sounds electronically. But we did not try to transpose, say, the aesthetics of Stockhausen into rock music. We tried to invent our own. Each of us had different musical backgrounds. The aesthetics of Can were that we brought these influences from everything that was new in the 20th century and tried to make something our very own out of it."

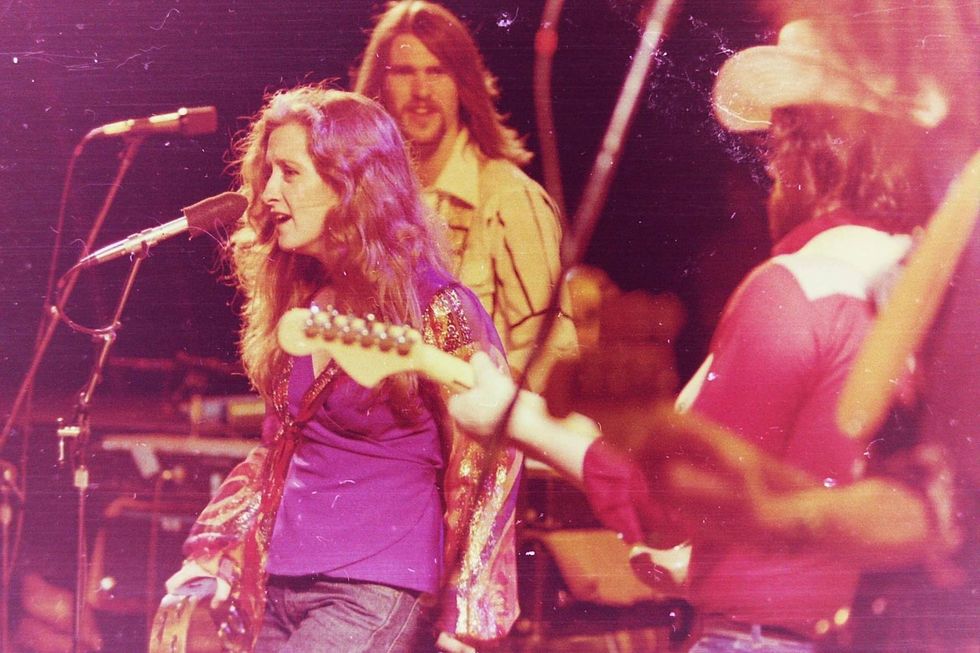

During their early days, Can exclusively used amps made by the Farfisa company of Italy. Later, they built a wall of amplifiers—partially visible here—that they transported to concerts, although guitarist Michael Karoli also

played a Fender Twin. Photo courtesy of Spoon Records

After that first performance, Can took up residence at Schloss Nörvenich. There, they recorded their debut album, 1969's Monster Movie, which featured American vocalist Malcolm Mooney, and established the hallmarks that defined their sound. (Monster Movie also featured one of the band's best-known tunes, “You Doo Right," which was the result of a six-hour jam, edited down to 20 minutes for the album. Thin White Rope, the Geraldine Fibbers, and other edgy rock outfits have covered the song.)

The first of Can's hallmarks is what the band called “instant composition," which didn't mean jamming—although they did jam for hours at a time. It meant using disciplined jam sessions to discover ideas for future improvisations. They reworked those ideas with every performance, so their music was always evolving.

“We started from nothing and tried to find something," Schmidt says. “If there was something coming up, you felt it. If there was something really nice, we repeated it, maybe, but every time we repeated it, it became quite different. It was never like a written piece that we rehearsed."

That concept applied to concerts, too. “We never played the pieces live as they were on the records," Schmidt continues. “We totally invented the music on the spot. We used themes and melodies, but it might have happened that the singer was singing one song while Holger was playing a bass part from another piece and I was making sounds. Sometimes three or four pieces appeared in a new improvisation and disappeared."

“There was a structure or a basement for the pieces, but other stuff was improvised," says Damo Suzuki, the band's second and best-known lead singer. “I was stoned enough and I did some different things. We didn't talk about which songs we played. We never spoke about that stuff. Before the concerts, there was no meeting about the music. Every concert was like that—we didn't run over anything ahead of time."

Instant composition was still a defining principle 10 years on. “Spontaneity was the hallmark of this unique band," says Rosko Gee, who worked with Traffic, Johnny Nash, and many others. Gee played bass on three Can albums in the late '70s, after Czukay switched from bass to what could best be described as “samples." “Each individual had more than enough character to lead. There were no constraints on me and, of course, with such a drummer, it was easy to groove. If you could imagine taking a whole year to decide on the material for an album, then the process was indeed thorough."

In the studio, instant compositions morphed into edited pieces. Can had the luxury of a home studio, which was a rarity for the times. Although it was primitive, they had enough recording gear to cut all their early albums at Schloss Nörvenich. Czukay doubled as the band's sound engineer and editing was his responsibility.

“It was done with a razor blade, tape, and paste," Perfect Sound Forever's Gross says. “Compared to what you can do digitally, it was painstaking insane stuff that took a long time, but these guys were dedicated. It was the same thing that some of the early tape composers, like Stockhausen, did."

Can's setup was minimal, even by the standards of the late '60s and early '70s. “The first five records were recorded with two Revox stereo [reel-to-reel] machines," Schmidt says. “You could only do one overdub and then the quality would suffer too much. We recorded on one Revox, and then, if we wanted to do some overdubs, we overdubbed from one machine to the other. And that was it. There was no mixing. When we played, the mix had to be perfect. Everybody was responsible for the balance. What he heard in his earphones would have been already the final mix. It was a good education to listen to each other."

“It was quite primitive at the castle," Suzuki confirms. “We only had two tape recorders and not many channels. It was almost like one or two microphones for recording the whole thing. My vocals went straight to machine. Holger was playing and doing the technical things as well."

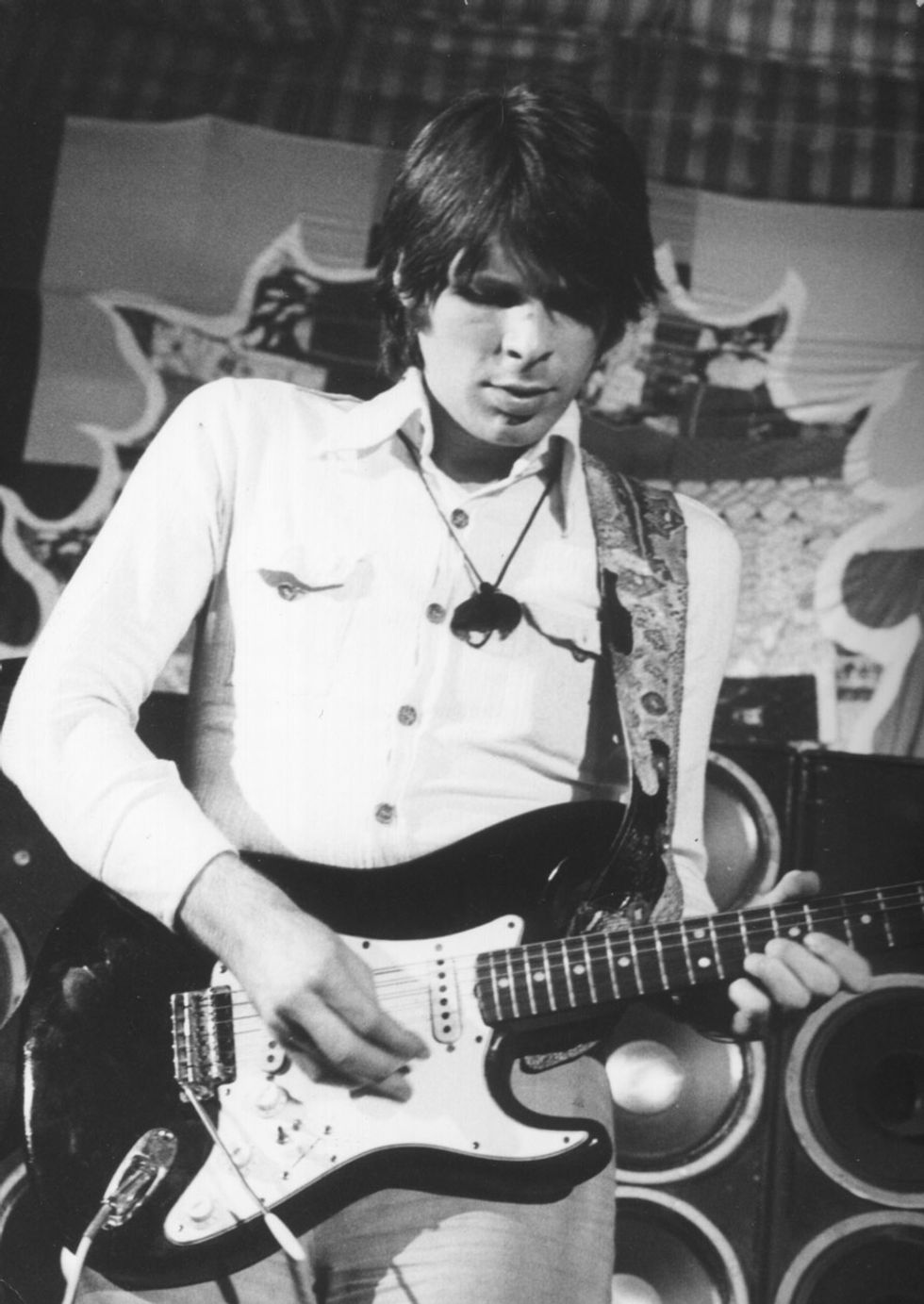

comfortable with the chicken-scratch rhythm of James Brown's Jimmy Nolen as he was with atonality and dissonance. His guitar of choice was a Fender Stratocaster. Some of his instruments were customized with an onboard ring modulator. Photo courtesy of Spoon Records

Can recorded the tracks that became the 1970 album Soundtracks at Schloss Nörvenich. Most of the music was taken from work they had done for films, which, Czukay is quoted saying in interviews, was how they paid their bills in the early years. Soundtracks was the first album to feature Suzuki. Then, in 1971, Can recorded what many consider their magnum opus, Tago Mago.

Can, Squeezed into One Can

Tago Mago captures everything great about Can. It's a double LP chock-full of lengthy, sprawling grooves, instant compositions, radical tape edits, moody soundscapes, and tongue-in-cheek weirdness. The first disc is especially groove-centric and features, as all of side two, the 18-minute-plus “Halleluwah." Disc two is more spacial and avant-garde—a testament to Czukay's early experiments with tape editing and using radio sounds.

Tago Mago is also a stellar example of Czukay's bass playing. He usually favored a short-scale Fender Mustang, although you sometimes see him pictured with a Fender Jazz, and he often performed minimal, repetitive, ostinato figures in the instrument's middle and upper registers. His style had evolved from his note-ier playing on Can's earlier records, and complimented drummer Liebezeit's busier, although similarly repetitive, style.

“It went together with Jaki's drumming," Schmidt says about Czukay's band-centered approach to bass. “Sometimes the bass drum had more of the function of the bass than the bass itself. Sometimes his bass playing was symphonic, like a huge bass figure in a classical piece. But sometimes he played it very sparse, very few notes, which he repeated throughout the piece. Sometimes Holger played a riff of three tones—it had no harmonic changes, nothing—and that was very important for Can, this kind of minimalism. It was the influence of James Brown."

Czukay also sometimes wore gloves when he played bass. “When we made film music, I once took him with me into the editing room," Schmidt says. “At the time, there was no computer, there was still tape, and they were working with these white gloves because this tape was very poisonous. He got fascinated. But it was more of a joke. It was just show, because it looked strange." Suzuki adds, “I don't know, maybe he didn't want to damage his fingers or something. Or maybe he wanted to eat sweets and have a coffee in the other hand. I don't know why he had white gloves on."

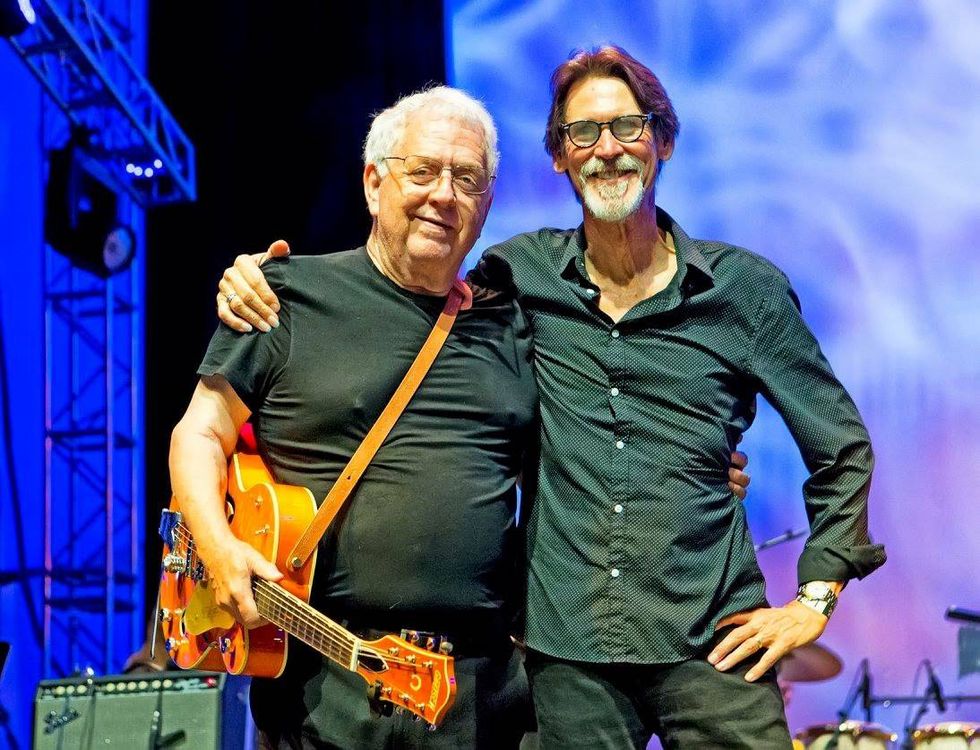

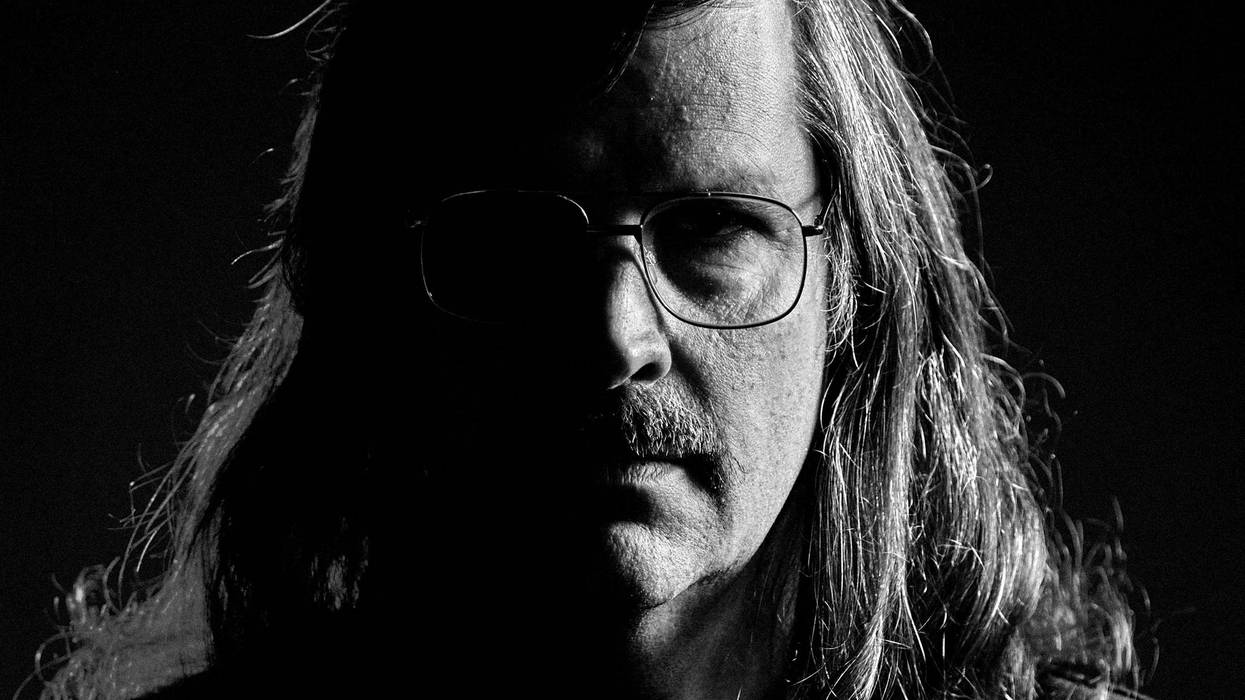

Can co-founder Irmin Schmidt questions whether the group even played rock, rather than contemporary classical music. Schmidt was a student of visionary composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Tago Mago is also a showcase for Karoli's guitar playing. Karoli gave Can their “rock" edge—at least according to most critics, which usually meant he used distortion and played minor pentatonics. But his playing was much more than that.

“Michael's sense of melody is totally different because, I think, it has to do with that his family comes from Romania," Suzuki says. “They were Gypsies—bohemians. They had their own music and their own life and things like that. He maybe got things from that area and that's why he had different melodies. Also, Can was a German band. The movement at that time, in the '60s and at the beginning of the '70s … most of the bands you categorize as krautrock music, they were provokating against the western culture. Everybody liked to make something different."

Similar to Czukay, Karoli was a minimalist and played repetitive figures with only minor variations, and he was fascinated with non-Western rhythms. “Michael's guitar playing was unique in its deliberate simplicity and directness," Gee says. “You can hear the strong Caribbean and Afro preferences in his strumming. He was a master of abstraction and his simple approach gave the band an effective width for divisive encounters."

He was also a master at harnessing feedback, which, according to Schmidt, was the natural bridge between Stockhausen and rock. “Jimi Hendrix had a big influence," he says. “That's why we used our instruments in an unconventional way. A lot of Michael's sounds are feedback. Sometimes onstage he was just in front of his loudspeakers and let the guitar sing by feedback, just by moving the guitar. Of course, that whole aesthetic has a lot to do with contemporary classical music."

Karoli played a Fender Strat through a Fender Twin—although he used a Farfisa amp in the band's early years—and had a Schaller fuzz pedal (a silicon Fuzz Face derivative) and a wah. “He had a ring modulator built into the guitar," Schmidt says. “I had an Alpha 77 synthesizer, which was custom-made for me. I could ring modulate the oscillator with the organ or the electric piano. Ring modulating was actually one of the basic tools of the early electronic Stockhausen music. We decided that it would be nice if the guitar could also be ring modulated."

Crescendo and Diminuendo

After Tago Mago, Can left Schloss Nörvenich and moved to an old cinema in Weilerswist, Germany, also near Cologne, where they set up Inner Space Studio. They recorded the albums Ege Bamyasi and Future Days. “Spoon," which was originally released as a single and also appeared as the final track on Ege Bamyasi, peaked at No. 6 on the German charts in early 1972. It became their closest thing to a hit, with the exception of “I Want More," which charted in the U.K. and landed them an appearance on the Top of the Pops in 1976.

At some point, they also abandoned their massive collection of Italian-made Farfisa amps and replaced them with a giant homemade wall of speakers. “That was our own construction," Schmidt says. “It was a huge wall behind us and was small speakers and big speakers that were randomly distributed on this wall. That was absolutely fantastic for Michael to create feedback, and it made a good sound. The only disadvantage was it was behind us and was sort of replacing the PA, so we had an enormous noise behind us. It was so beautifully made and made a very peculiar, beautiful sound for feedback and electronic sounds. But then the whole thing changed and we didn't use that wall anymore because it was very hard to transport. Later we had a very nice JBL PA, but for very big gigs we used the wall as a monitor."

Suzuki left Can in 1973, after recording Future Days, and the group carried on with different members providing vocals. They mimed their 1976 performance on Top of the Pops with Czukay on upright bass and a “fake" Karoli on guitar. “'I Want More' got into the charts," Schmidt says. “We were all on holiday. Holger and me were in Yugoslavia—in Croatia—with a whole bunch of others. Jaki was in Cologne. Virgin Records called and said, 'You got into the charts and you were asked to be on Top of the Pops. You have to come immediately.' Michael was in Kenya and we couldn't get hold of him. Virgin insisted that we play, so we did it without Michael. He was replaced by somebody who definitely looked different so that everybody realized that this guitar player wasn't him."

In 1977, Rosko Gee and Rebop Kwaku Baah from Traffic joined Can on bass and percussion. Czukay focused on making sounds using shortwave radios, tape recorders, and other devices. “Holger decided to do some more experimental electronic stuff and asked Rosko to join the band," Schmidt says. “Rosko played bass and Holger did weird sounds." It was something he had experimented with since the '60s and, in many ways, his pioneering work is considered a precursor to modern sampling.

“He was doing it even before Can," Gross says. “The first real solo album he did, [1969's] Canaxis 5, sampled a Vietnamese woman singing as part of the music. He told me that a huge influence on him was 'I Am the Walrus' by the Beatles. He was really entranced by the voices at the end of the song."

But Czukay's move from bass was the beginning of the end of the band. He left in late '77 and Can broke up two years later. They continued to work together on various projects and even reunited on occasion. Czukay worked on different things as well, collaborating with Jah Wobble (PiL), the Edge, and many others, and continued to explore. “He really dived into techno," Gross says. “I think that was something that was made for him, and in a lot of ways he predated it. He saw how it fit into what he had been doing for years and he just embraced the hell out of it. That just shows you he had this adventurous spirit, even in his later years."

Karoli died in 2001 at the age of 53. Liebezeit and Czukay both died in 2017 (at ages 78 and 79, respectively). But Can's legacy lives on and their influence only seems to increase with time.

“Every 10 years, young bands say, 'Our influence comes from Can,'" says Suzuki. “When punk began, some punk bands mentioned our influence, and then new wave comes and they mention us, and then trance comes, and now some hip-hop people are using our songs as well. It is strange, because we are already more than 45 years on and people still listen. It is something. But it is crazy, because it is a half century, man."

Essential Can

Get an earful of Can with these tunes that showcase guitarist Michael Karoli and bassist Holger Czukay.Bassist Holger Czukay applies the white-glove test to the The Old Grey Whistle Test in this 1975 live BBC-TV performance. Dig the intensity—and Michael Karoli's off-axis blues-rock soloing on his trusty Stratocaster.

The psychedelic side of Can leaps out in this tune from Tago Mago, the band's first album with Damo Suzuki. Michael Karoli drives the performance with his era-perfect fuzz solos and funky chording, and the band is framed by their Italian Farfisa amps.

“Hey you! You're losing your vitamin C," Damo Suzuki cries over the airy arrangement of, naturally, the song “Vitamin C," from Ege Bamyasi. Michael Karoli keeps it minimal on guitar while Holger Czukay exercises one of his trademark bass strategies: repeating a handful of notes.

At this point, Rosko Gee had replaced Holger Czukay on bass, allowing Czukay to create the tape manipulations in this live version of “Moonshake" from Future Days. The beauty and surprising accessibility of Can results from the band's belief in the power of the groove.

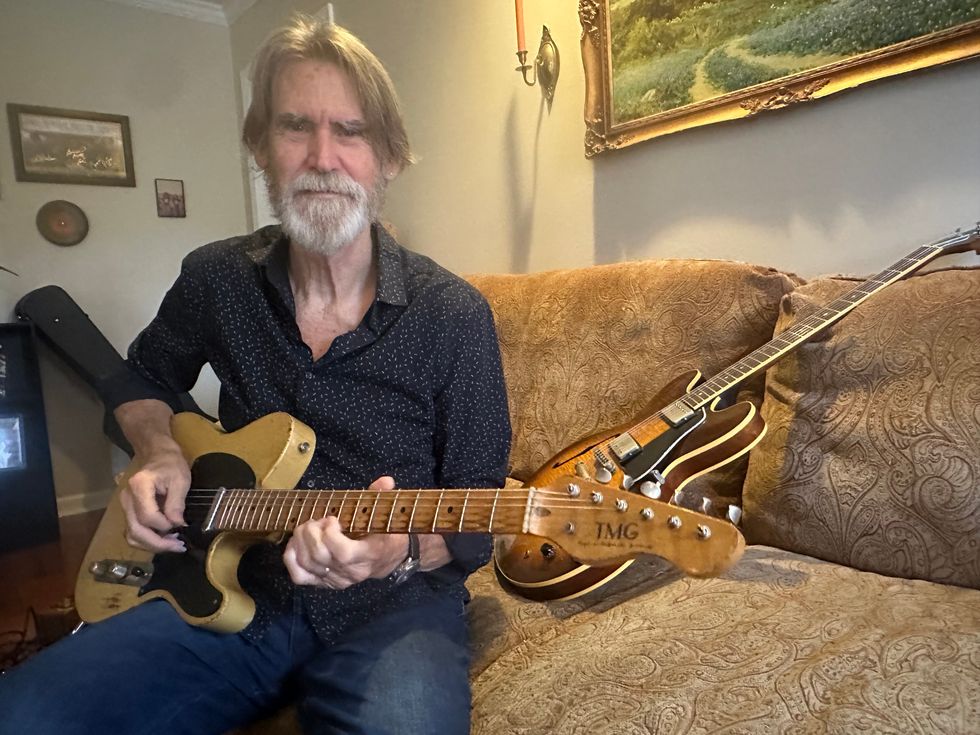

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski