|

Let’s start right at the beginning – where did the motivation to get into this crazy business of building guitars come from?

Let’s start right at the beginning – where did the motivation to get into this crazy business of building guitars come from? Well to be honest, it came about because I became aware, through some friends, of people who had gone to a guitar making school somewhere. And for me, at that young age, that was quite a revelation. I loved to play music, but I didn’t really feel like I was good enough or had the right temperament to be an artist.

So you headed to the Earthworks School of Luthiery in Vermont at age 18. What was the general atmosphere like at that point?

That was back in a heady period when people decided that you could build guitars. If you go back before about 1970, the idea of building a guitar in this country, as an individual, was not really something that you could even think about. Back then if you told someone you made a guitar their jaws dropped – now they tell you about two others they know who do that.

Why was that such a jaw-dropper back then?

Because there wasn’t a lot of knowledge available, and also because there weren’t many outlets where you could buy the necessities – the tools, the equipment and so on. Nowadays, guitar makers use electric routers for building at home; before 1960, if you didn’t have a shaper table and a lot of expensive equipment to do the operations, you weren’t gonna get it done. The stuff we have today didn’t even exist back then. So when people talk about building guitars by hand, I think it’s relative to the period of time they were working in and the economic realities of that time. Many builders today could not build guitars using nothing but hand tools, like the old European builders did.

Describe what the experience in Vermont was like, being surrounded by like-minded people and finally getting to build guitars.

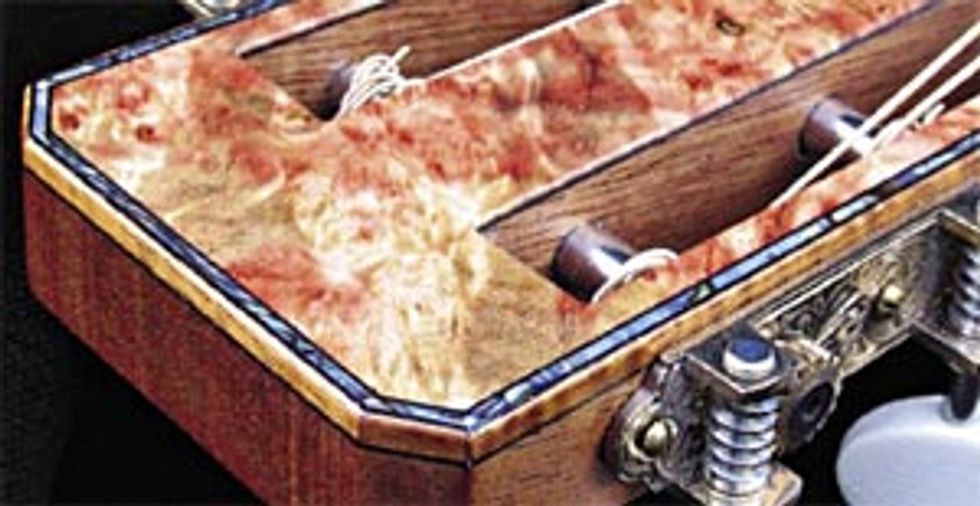

I worked for six weeks with Charles Fox. Charles had been a schoolteacher in Chicago, and he moved to Vermont with this dream of setting up a guitar business. He worked there as a schoolteacher for a short amount of time and built this incredible, octagon-shapped log house and a couple of buildings called yurts. They were supported by a cable that ran around the top of the wall, all the way around the building, but the walls all leaned out. The roof was covered in some green foam material, but originally the covering for the corrugated roof was dirt.

It was kind of an interesting time – this was 1976, and we were coming right out of the counterculture generation. There were eight of us, and we all lived in those yurts. We got up early every morning and went up to the shop and listened to Charles lecture for an hour, and then we sort of worked through the guitars together each day, one process at a time.

Charles was a very good teacher, and he knew how to use hand tools and such. Thinking back on that experience, that was the most valuable thing I got out of it. He really did teach us how to work, and he taught what was possible and what was not. Of course, a lot of the building methods we were using have long since been abandoned, and a lot of the approaches we used then, I don’t use today. But whenever I pick up a hand plane and start planing a top, I use those basics he taught us. It was a good foundation.

After your six weeks in Vermont, did you go back to Georgia and make it a point to go into the guitar business?

I don’t know if you could call it a conscious effort to go into a business endeavor – I just wanted to build guitars. I had spent several of my teenage years in Georgia, and lived with some friends when I returned. I actually worked as a dishwasher at a restaurant, and as a cabinetmaker in a lumber mill while trying to figure out how to build guitars when I had time. Nonetheless, by the time I left Athens, I had already made something like eight guitars.

Classicals?

Actually I was building both classicals and steel strings at that time. I figured out early on that trying to make a living building classicals was pretty much impossible. I really didn’t get serious again about trying to build classicals until 1984, and then I built quite a few classicals. When I moved to Nashville in ‘85 that was really all I was focused on.

What was the motivation to move to Nashville?

Starvation [laughs]. I got a job offer down here at Gruhn Guitars, and it was kind of a lark. I called up and talked to George one day, and when he found out I knew Robert Ruck, he was very interested in me coming down. I shipped them a guitar I had built and then was invited to come work for a week. At the end of the week I was asked to sign on and I moved to Nashville.

When you started at Gruhn’s, you did a lot of repair work. What was the biggest adjustment you had to make there?

You get exposed to everything in a place like that. My biggest struggle was trying to figure out what was appropriate to do on each job – how much time you would spend on this instrument, as opposed to another one. You could go way overboard and waste a lot of time on something that didn’t have a lot of return. Gruhn’s was a commission environment, and so it was critical to not waste your time.

You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that Gruhn’s was a professionally competitive environment. Did that push you to improve your work?

It was the only time in my life where everyday I was around other people with abilities that were parallel to my own. The foreman of the shop was Kim Walker, and the person who I came in to replace was Matthew Kline – Matthew now does most of the CNC operations here at the Gibson factory in Nashville. Kim and I became good friends during those years, but it was kind of brutal because we did try to outdo each other, no question about it. Years of experience were passed on in that shop and it was a special thing to have been a part of.

What was the most over-the-top operation you performed there?

Well, George had a 1927 00-28 that had herringbone around the top and in the rosette and there was just a big, gaping hole right where the bridge sat. There was no area to glue a bridge on. And George said, “Fix it. Make it go away.” Well, that guitar sat around and sat around and no one would touch it.

So one day, I pulled it out and was laughing at what George wanted us to do, which was patch something right in the middle of the top – to keep it original. So I went and visited him, and said, “This is ridiculous, we’re not going to fix this top. It is beyond reason; why don’t we just replace the entire top?” He never wanted anyone to replace a soundboard, because he wanted all of the binding and rosette to stay original. So I said, “Look, I’ll put the rosette in the new top, and I’ll drop the top inside the original bindings, and I’ll make it look like it never happened.”

He finally relented, and I developed a technique for routing in a top to fit inside the binding channels. You basically just attach a top to the soundboard – you can use carpet tape – center it up, and then use a routing tool where you calibrate the width of the bindings. You route the top outline out so that when you put in the new top it is as close as you can fit it to the original herringbone. Next, you take a routing tool, go around and ever so carefully trim the wood away from the black line. Then you brace the top and it just slides right back into the guitar. You might have to do a little fitting, but at the end of the day, that guitar had its original binding work and rosette in it. I used a 35 year old German top, did a shellac finish over it and then slightly distressed it, so it looked original.

How has that affected your own work as a luthier, having worked so closely in those traditional settings, where George doesn’t want you to replace anything?

How has that affected your own work as a luthier, having worked so closely in those traditional settings, where George doesn’t want you to replace anything? Not really very much, I would say. The thing I would take away from it all, which is most relevant to building my own guitars, is to look at the longevity of the instrument and to see just what long-term stress will do to a guitar. The impact of the various designs is very telling and it was a good yardstick for understanding the history of American guitar making.

Your guitars have been in some famous hands – Earl Klugh used one of your guitars on Solo Guitar, a seminal guitar album. I’m sure a lot of luthiers would jump at a chance like that. How did that come about?

In my experience, the best way to work with well-known guitar players is to not try to work with well-known guitar players. I did not know Earl Klugh when he bought that guitar or made that record. Likewise, I didn’t know who Muriel Anderson was when she bought one of my guitars – she bought it from someone else in 1986, and it was a guitar I had made in 1983.

You know, the guitars really just go out and if they’re good, they’ll find their way. If they’re not good, they won’t. It’s just that simple.

But what’s it like getting to hear the music made through something you put together with your hands? That’s got to be difficult to describe.

But what’s it like getting to hear the music made through something you put together with your hands? That’s got to be difficult to describe. I feel a little humbled when someone who is as skilled as one of these great players would choose what I make to work with. And that’s something that’s important to distinguish – I’ve never been a guitar maker who goes out there just trying to get ahead by giving away guitars. The few occasions that I’ve attempted to do something like that, I’ve regretted. It never really works out.

The only way it ever works out is if there is a true artistic connection between a player and a guitar. You’re not going to take Willie Nelson’s old Martin away from him. And when that guitar was made, whenever it was made, it wasn’t made for Willie Nelson. Nobody was thinking, “This guitar is going to be one of the most famous Martins ever made.” And I think some of that happened with me, in a fortunate way, early in my career. But it was somewhat frustrating because you didn’t see the benefits of it right away; there wasn’t success just because so-and-so played your guitar.

Which is another thing to be aware of – a lot of people’s approach to the business today is to chase the players. I don’t know if that’s a good thing for anybody, to be entering into those kinds of relationships. I think it’s much better if it comes about in a natural way and if people develop a true affinity for their instrument.

And at that point, the artist’s expression will be truer.

Absolutely – at that point, it becomes real. You can build something really good but it’s not necessarily going to be good for everybody. You can say, “Okay, I’m going to take the bold step and make a deal with some artist, and I’m going to give them a guitar in exchange for their endorsement.” But I’ve seen that happen a lot of times where that process yields an unhappy artist and an over-extended guitar maker. So the artist feels obligated, and the guitar maker doesn’t quite understand why what he built isn’t good enough. I just wouldn’t want to be promoting myself in that way, because to me, it’s not a real honest interaction.

Could you talk about your connection with Chet Atkins?

Could you talk about your connection with Chet Atkins? It mostly happened because we both lived in Nashville, and because there wasn’t a lot creatively that went on around here that Chet didn’t know about. Around the time I arrived here in ‘85, a mutal friend introduced me to him and it was a very cursory introduction. I doubt he would have even remembered it.

But one day I was working at Gruhn’s, and I got a call to come down to the showroom. So, I went downstairs and Chet was there with a later model Martin D-41 Tony Rice had given him. He pulled it out of the case and said, “I was wondering if you could pull a little bit more sound out of this for me.” I looked it over – and I was a little bit intimidated, obviously – and I said, “Well, sure, we can loosen it up a bit for you.” I was kind of shocked and amazed that the guitar was setup with nickel-wound strings and the action was real low – so low I couldn’t have played it. So I opened it up some, and sent it back to him.

Later on, in 1990, I wanted to shoot a video, and I asked Muriel to perform on it, a few months after she won Winfield [the National Fingerpicking Championship]. She and John Knowles did this video for me, and after the shoot she was going to go over to Chet’s office, and invited me along. So I went over and when I was introduced to him I was standing across the room from him; when he heard my name he came at me like some sort of very happy pet, like he was very enthusiastic. It was surreal. He just talked my ear off for 15 minutes, wanting to know everything I knew about guitar making.

I learned later in life from John Knowles that Chet tried to overcome people’s reactions to him by putting them on a pedestal and treating them like that.

Did you work with Chet after that?

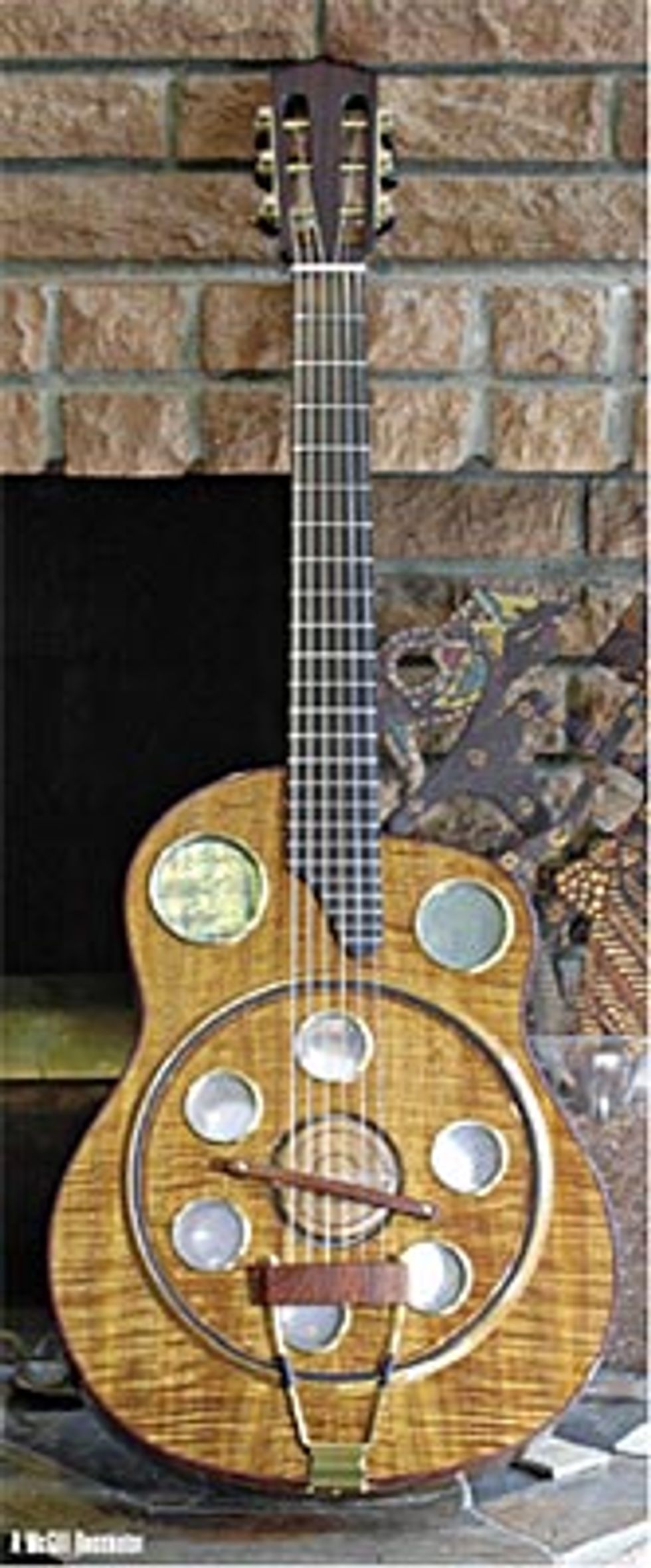

Well, I became very friendly with Chet as years went by. When I started building resonator guitars for Earl Klugh in 1992, I called down to Chet’s office, told him what I was doing and asked if he could loan me a Del Vecchio to look at. And he said, “Sure, stop by the office tomorrow and I’ll have one here for you.” So I went down and picked up one of his Del Vecchios, and took it to my shop to examine it. I told Earl what I had, and he said, “Wait, that’s not the guitar that I want you to build for me. He’s got a little one with a short scale length. I’ve got one here that’s not very good but I’ll send it to you.” And he sent me this modernera Del Vecchio, and I sort of started building resonators from that.

After I made it, Earl asked me to build a bunch of them and he gave one of them to Chet. From that point I made Chet two more, and sometimes he would come by the shop while I was working and just hang around, tell stories and jokes. He was very amusing.

Our relationship was so unassuming, really. One day he was hanging around the shop and somehow the subject of Hank Williams came up. And I, in a very nonchalant way, because I thought he might know the answer to the question, said something like, “Chet, who played guitar for Hank Williams?” And he whipped around and said, “Well, I did!” And I honestly didn’t know that! It had gotten to the point where it was like hanging out with your friend, and that was a bit of a reality check.

The thing about Chet was that he never forgot what it was like to be struggling. He had an uncanny way of extending his hand at a moment when he knew people where having a hard time. Doyle Dikes told a story once where Chet called him over and gave him a guitar when his musical career was down. Tommy Emanuel talks about getting letters from Chet when he was a child in Australia, with tapes going back and forth.

He was a very special guy, and the experience of being in the Ryman Auditorium when his casket was walked out of there – it was a feeling of energy collapsing on the isle as if the whole room just wanted to go out that door with him.

You make a wide range of guitars – it seems like a lot of luthiers try to pick one design and hone it. Your versatility is impressive, and I’m wondering where it comes from.

Well, one of the blessings and curses of my career is that I started building guitars in a time when there wasn’t the big handmade marketplace that’s developed in the last 15 years. The result of that was I couldn’t rely on just one thing; as much as I wanted to build classical guitars, I was never going to compete with Robert Ruck or José Uribe, because the market was so small and those guys were so well established by the end of the ‘70s. Classical players would look at their guitars before they’d look anywhere else, so if I wanted to build classicals I’d have to sacrifice in order to be good at it.

Earl Klugh gave me a real gift – he helped me quite a bit 15 to 20 years ago. There were a lot of tough times when he would buy a guitar from me just to keep me going. He told me one day, “I want you to build one of those Del Vecchio guitars,” and I was very negative about it, because I was the artiste building classical guitars, right? The guy with the big flaming ego.

But he kept after me for months about doing it and I couldn’t tell him no. So in August of 1992 I decided to take the whole month and build this Del Vecchio-style guitar. There are pictures of me stringing it up and somehow I felt that my career was over, because I had built this thing that would ruin my respectability amongst the snobs that buy classical guitars. I probably actually even gave a damn about that back then, which was a big mistake.

After I finished it, I was surprised by how many players of all different types wanted to see it. I had three or four people waiting outside my shop for me to string it up that day. And Earl immediately asked me to build more of them. I was so frustrated trying to make a living from something that was traditional, and then I saw all this enthusiasm for something that was non-traditional, and I said to myself, “What am I seeing in this picture here?” All of these people that I’ve known for a long time, that have such conservative tastes in instruments, were actually responding to this thing in a positive way. And that’s when I realized that I don’t have to be like everybody else to be successful. I kind of changed gears, into a different way of thinking about things after that.

And you’ve been doing your own thing since?

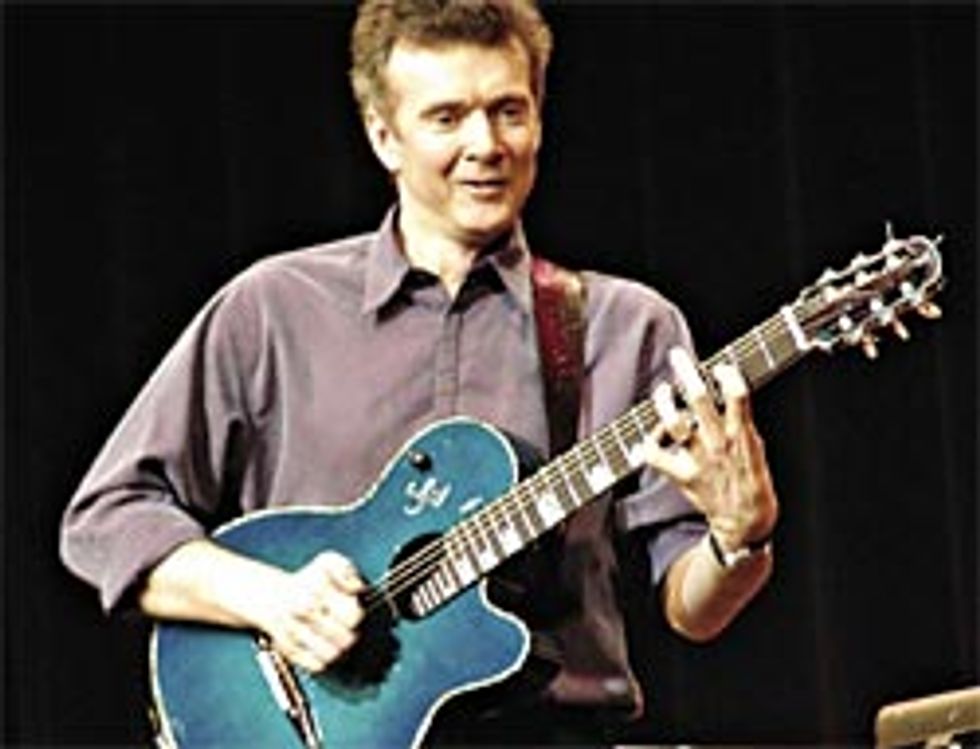

And you’ve been doing your own thing since? You know, it’s always been up and down. I think if you’re established and doing what’s popular, it’s easier in some ways. But if you’re building instruments that have their own aesthetic, then you have to get people to understand what it is, and that takes a little more time – you have to be patient. I built my first Super Ace guitar in 1998, and by the spring of ‘99 Peter White [award-winning jazz artist] was touring on it. In fact, he spent the first few years touring on one of the first three that I ever made – one that I just called a “prototype.” Once he had it and saw what it did, he didn’t want to play anything else.

So, I knew that I had something that really appealed to the people who needed it, because someone like Peter could play anything, but this one seemed to fill the bill the best. I feel like it takes three or four years before the buying public catches up with a reality like that.

Could you explain the modern structural system you developed and use in all of your guitars?

I am very taken with what is going on in Australian luthiery. I really don’t feel like building guitars with tops that are paperthin and with all this graphite and balsa wood in them is for me. They are some of the loudest guitars ever made, but I would never want to place a warranty on one. I started looking at how to take some of that conceptual knowledge in what they do and translate it into my own instruments. What it’s really all about, in my mind, is how to release more of the string’s energy into the soundboard, and part of that is to fully reinforce the structure to eliminate ambient modulus, which may mute or deaden frequencies you need. I started from that concept and built something that was more original to me.

I can tell you this: before I started doing it, it was a lot harder to sell instruments. It just adds a different motor to the sound of a guitar. It evens out things that might be dead or too powerful and it provides solidity in the low-end. I feel like the string energy factor just adds a certain amount of output.

And it’s not like this is the loudest guitar in the world – that’s what they are doing in Australia, trying to build the loudest guitars the world’s ever heard. If you want to push the parameters that far, well, okay – push your strength to weight ratio as far as you can get it. But I think if we can add some power to a traditional sound, a majority of players would be happy to have an instrument that’s responsive and has more of a musical tradition to it than some of these newer designs. Mind you, I’m not putting those guitars down, because I think they’re conceptually brilliant, but I wanted to approach it a different way.

Do you have thoughts about your legacy in the industry?

I started building guitars in the mid ‘70s, and it was right at the downward slope of the guitar making renaissance in this country coming out of the late ‘60s. The reason that I was even aware of it was because I used to go to Colorado in the summertime – I was in Boulder – and there were two guitar makers around that area. There was someone that my sister knew who had a guitar made by Max Krimmel, and they were very nice guitars. There was another builder out there whose name was Monty Novotny, who worked in Longmont, Colorado. And the reason why I bring this stuff up is because after 30 years – do you know who these people are?

I really don’t.

I really don’t. Exactly. If you were to read their resumes – Monty Novotny built guitars for John Denver and a host of other really big name artists in those years. Max Krimmel built guitars for Stephen Stills and Jerry Jeff Walker, among others. It’s kind of like… history is fleeting. Some things seem important at one point of time or another. And after 30 years of doing this I just wonder, have I done enough to leave something behind that people will recognize, that will be memorable? To me, it’s not just about whether you’ve made guitars for somebody that everyone knows. If you look back at the early 20th century, at what we had for instruments, you had the whole Gibson mandolin family thing, which was really created so you could have a new musical aesthetic. In the ‘20s you had an expansion – the L5 and the Lloyd Loar period – which is favored by so many traditional musicians today. In the late ‘20s, you have Martin’s introduction of larger-bodied steel string acoustic guitars and in the early ‘30s they took over with that concept. Everybody remembers these names and these people – they did something that was relevant, like Dobro, National, Martin and Fender. Every period of time we have these milestones, and people remember what they are. I guess I hope some of what I do may someday be viewed as credible in that way.

Do you view this as your art? Your expression?

You know, I do, and I struggle with the whole concept of how do you make more of them, because I’m so rooted in the artistic aspect of it. It’s hard for me to think, “Well, I’m just going to trash this approach because I can do something else more efficiently.” I’m currently trying to get some stuff that I’m doing oriented for CNC parts manufacturing, because [the Super Ace] is a fairly complex guitar to make otherwise.

So you struggle at the crossroads of commerce and artistic expression?

Yeah, I do, because I think I’m a lot more content when I’m just doing something new and winging it. It’s like you do something once and then you’ve got to reproduce it. Sometimes, the reproduction part isn’t as fun as the anything-goes side in the beginning; that feeling of creating something, using your senses and knowledge, that will appeal to somebody.

So looking back, how’s the ride been for you?

You know, I’ve had a lot of opportunities to interact with a lot people that I never thought I’d have known in my life. PBS was having a fundraiser recently and they were replaying the Glen Campbell Good Time Hour from the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, and there was Glen Campbell and John Hartford singing “Gentle on my Mind.” When I was that age, I would never have thought that I would know John Hartford, that he would come over to my house for a party and that we would sit around sharing stories about mutual acquaintances. I never thought I would have known Chet or Earl, or so many remarkable people.

What’s left to do?

Really, I think… how do you really know what’s going to happen? I guess make as much money as I can [laughs]. I figure if I build an extra guitar every other month for the rest of my working life, I can go on selling guitars until I die.

McGill Guitars

mcgillguitars.com

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.