Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

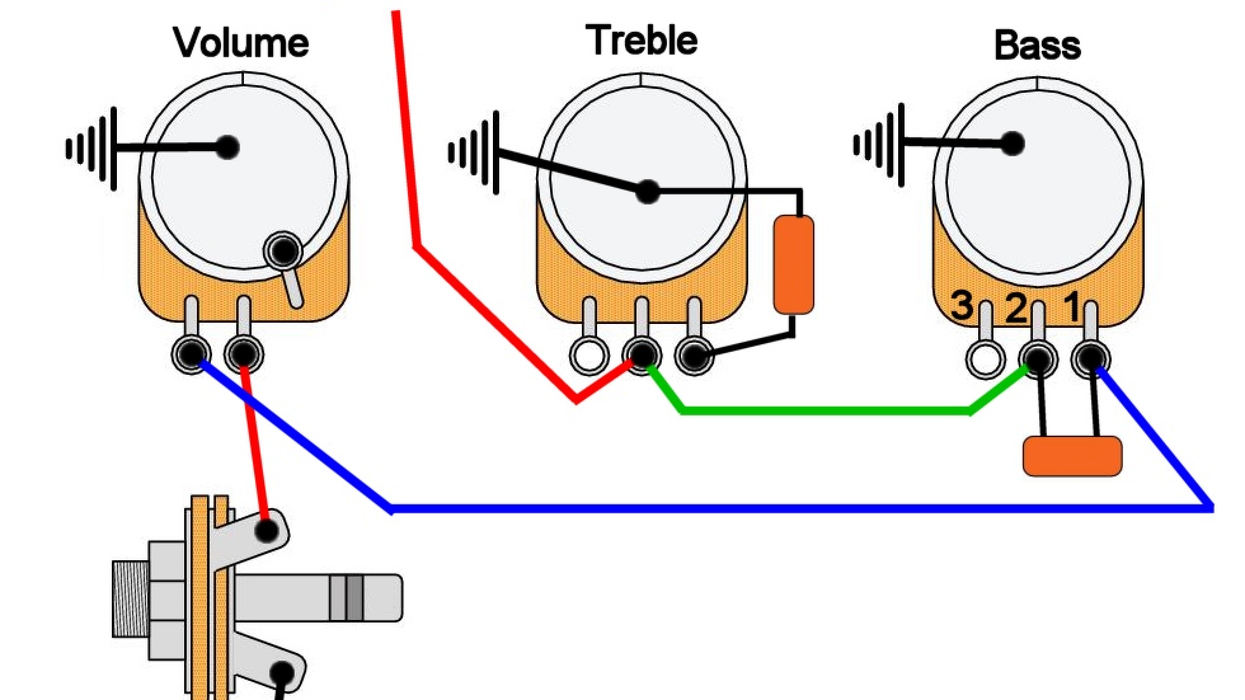

Mod Garage

Love to hot-rod your guitar? Let Dirk Wacker show you how to do it right. In his Mod Garage blog, he explores cool projects , shares wiring diagrams, and even manages to weave some historical perspective into the technical details.

Don’t Miss Out

Get the latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Popular

Recent

load more