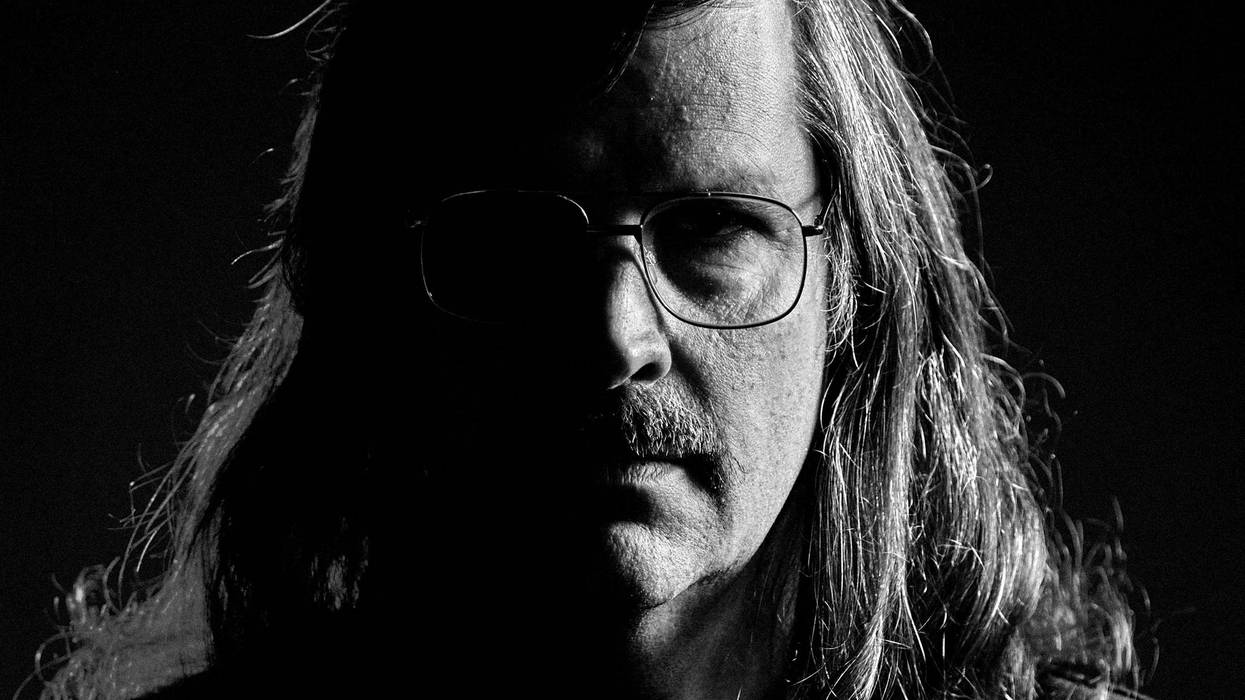

Now well into his sixth decade as a performer, with more than 20 albums behind him, singer-songwriter Chris Smither is doing some of his finest work. His vivid lyrics and resonant baritone on his new recording, All About the Bones, are elevated by his inimitable guitar style.

Smither’s acoustic fingerpicking is based on the legacy of bluesmen like Mississippi John Hurt and Lightnin’ Hopkins. “When I heard Lightnin’ Hopkins for the first time,” says Smither, “I thought that two people were playing. The fact that one guy was doing it all floored me. And then John Hurt’s use of syncopation, the subtle way that he does the dead thumb pattern so he can use the fingers to play lead lines—it took me forever to work it out.” But Smither takes these models and makes them his own. He gets a groove going, harmonizes the tune in double-stops, and all the while thumps the floor with the back of his boots as if he were a drummer in his own band.

“People told me I was crazy when I was coming up in New Orleans. They asked me why I was playing all this old acoustic music while the whole world was going electric. There were just a few of us … guys like John Hammond Jr. We felt a kinship, and he validated my choices.”

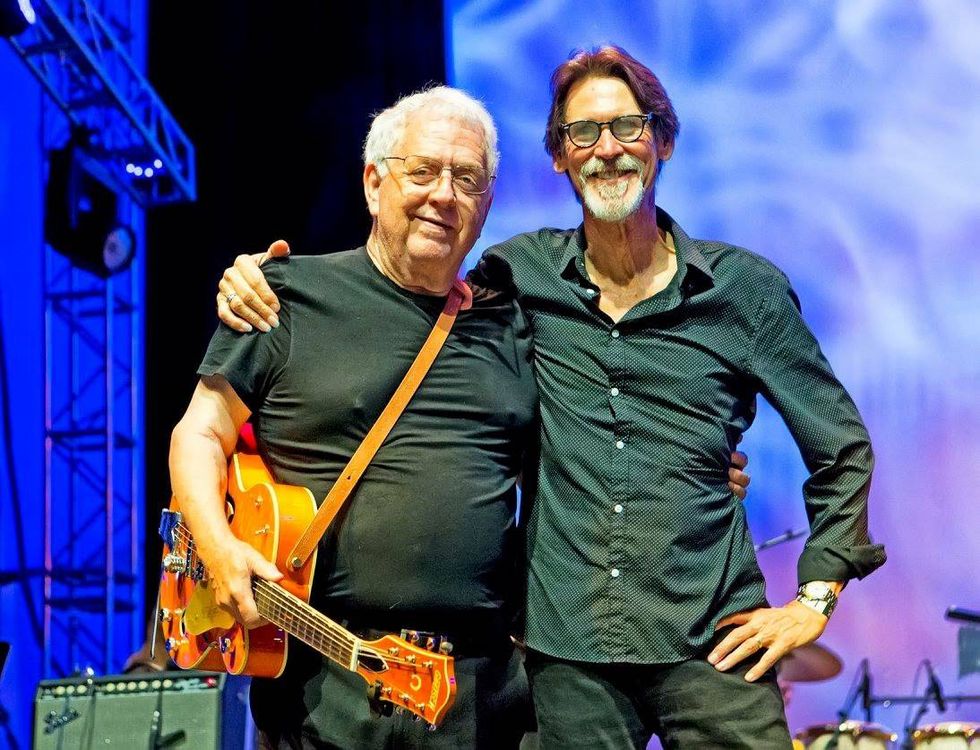

Firmly rooted and yet distinctly contemporary, Smither is the rare performer whose music feels both timeless and timely. The scaffolding may be the blues tradition, but the house Smither builds is all his own. Musically, that means different chord types, different forms than the 12-bar pattern, different picking patterns. His words are deeply philosophical, wry, bittersweet, traipsing through shades of light and dark. They’re rich with allegory and a kind of street mysticism, and they beg for repeated listens. The album’s arrangements, minimal and intimate, feature Zak Trojano on drums, BettySoo on harmony vocals, and producer David Goodrich on, as Smither puts it, “a carpetbag of instruments.” But most often when you see Smither, who is 79, it’s alone onstage, delivering songs like a troubadour who splits his time between a Crescent City street corner and the spirit world—which may actually be the same thing.

All About the Bones - Chris Smither

I asked Smither how he developed his approach to lyric writing. “Coming from the blues base, I had to admit that I’m not a sharecropper, I wasn’t going to write about 40 acres and a plow. I’m the son of a university professor. You write what you know. So I talk about the things I’m interested in, and that turns out to be what most people are interested in—life, death, love, hate, why am I so miserable, and how am I going to feel better. A huge marker for me, believe it or not, was 1968’s Disraeli Gears by Cream. I thought, ‘These guys are a blues band, but they’re making it their own with contemporary sounds and lyrics.’”

Nonetheless, “The two main guys for me were Randy Newman and Paul Simon,” Smither relates. “Newman is painterly, he creates an indelible picture. It’s like the photographer Matthew Brady from the Civil War; it’s all there to take in. Paul Simon helped me understand how words feel in the mouth, that they have intrinsic value beyond their meaning.”

Like Simon, Smither finds a melody and then makes vocal sounds, sometimes intelligible, sometimes not. All the while he’s thumping out those Delta-inspired grooves. “Half the time I write songs, I’m halfway through before I have any idea what they’re about. I get a tune in my head and just start making funny noises, a conversation with that part of the brain we’re not on speaking terms with. Then I’ll sit back and ask ‘Where is this going?’ Eventually a little light comes on and I start to see what the song needs. Then the left brain takes over, and I can be more diligent about it.”

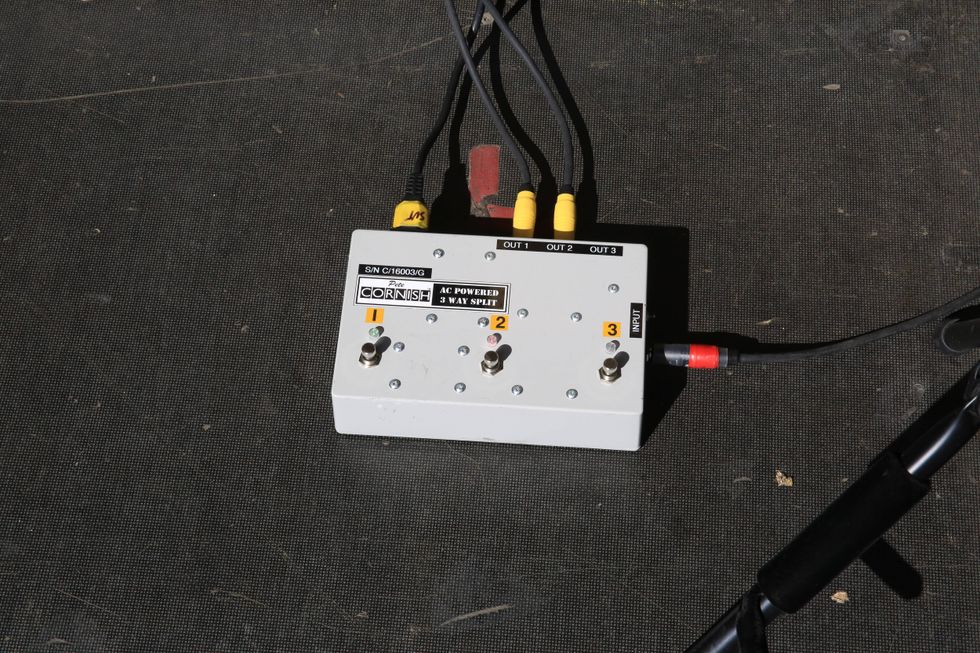

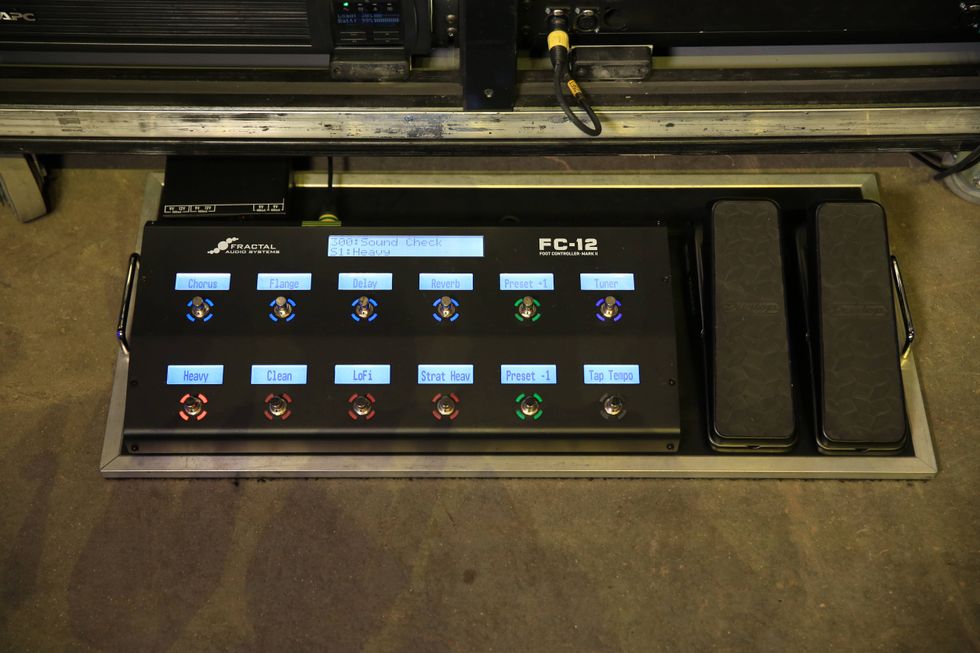

Chris Smither's Gear

Smither onstage with his current favorite instrument, a custom Collings cutaway with strings ranging from .013 to .053.

Photo by Carol Young

Guitars

• Collings custom 12-fret cutaway

Tuner

• Boss TU-12H

Strings & Accessories

• Elixir (.012–.053 sets with a .013 substituted for the high E string)

• Shubb Capo

“People told me I was crazy when I was coming up in New Orleans. They asked me why I was playing all this old acoustic music while the whole world was going electric.”

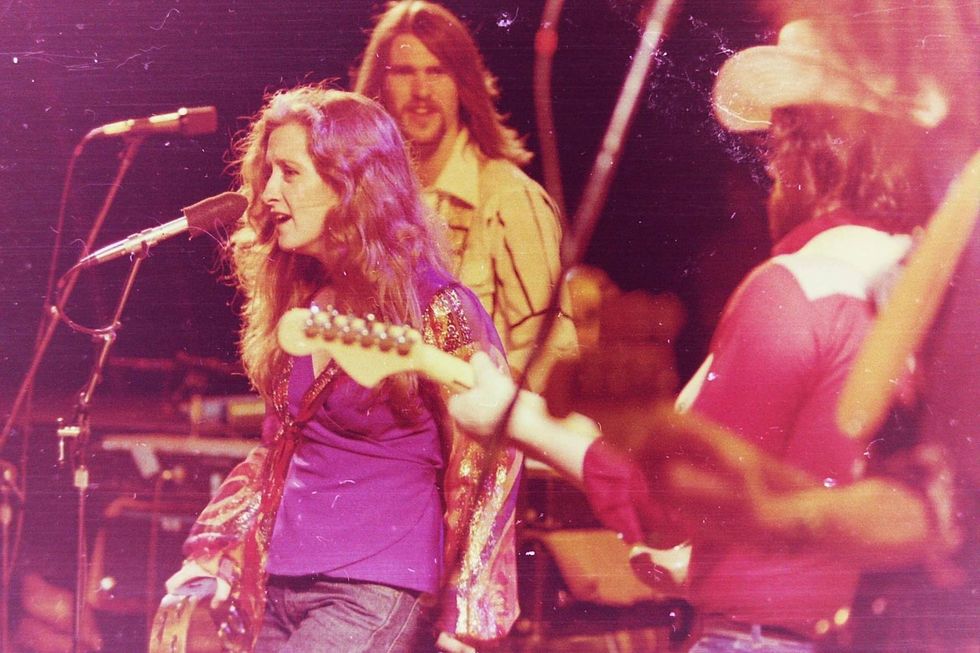

As a young man, Smither had a break that every songwriter dreams of when, in 1972, Bonnie Raitt covered his song “Love Me Like a Man.” The two were part of the folk and blues scene of Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the late ’60s. Subsequently others would record this gem, including Diana Krall. Emmylou Harris made another Smither tune famous: “Slow Surprise,” in the soundtrack of the 1998 Robert Redford movie The Horse Whisperer. All this built his reputation, but Smither’s daily bread is one-nighters across the U.S. and in Europe. He’s developed what he calls “a small, incredibly loyal” following.

“I can see phases of my career,” Smither says when asked how this latest record might differ from his youthful work. “The last three records or so have been a refining of my vision, though if you asked me to define that vision, I’d be hard-pressed to do so. On the one hand, you can listen and say there’s nothing new here. But on the other hand, I’m not doing things that are unnecessary. Everything’s getting stripped down. The record sounds full to me and yet there’s so few people on it.”

As befitting a man about to turn 80, many of the songs on All About the Bones deal with love and death, such as “In the Bardo.” The bardo is a Tibetan Buddhist term that refers to the intermediate state after death and before rebirth. Smither says,” I was more than halfway into this, with all kinds of lines and material, but I just felt lost. And that’s when it occurred to me—where am I lost? I’m lost in the bardo. Once I recognized that, I could put the whole thing together.

Smither’s new album, like much of his finest work, is about, as he puts it, “life, death, love, hate, why am I so miserable, and how am I going to feel better.”

“A huge marker for me, believe it or not, was 1968’s Disraeli Gears by Cream.”

“I’ve always wanted people to understand the songs the way I do,” he adds, “but it’s even better when they come up to me and say, ‘I understand that song perfectly,’ and I go ‘really?’ And then their explanation bears no relationship to my concepts, and yet makes perfect sense. I tell them, ‘You’re absolutely right.’”

It's heady stuff, and yet Smither makes his “In the Bardo” feel down-to-earth—his warm, gentle fingerpicking that splits the difference between John Hurt and the modern American-primitivist school inviting the listener to embrace his lyrics: “Deep into the shadows / It’s on the way, on the way now / No answers to the questions / No sense of direction home / Just a subtle indication / a whispered invitation to let go.”

“You’re headed towards a cliff,” Smither says with a half-smile,,“and you have no idea when you’ll go over. You ask, ‘What the hell am I going to do now?’ I like to talk about this stuff. Ideally, nothing comes as a surprise in life. If you’re prepared, nothing can throw you.”YouTube It

Chris Smither plays his beautiful contemplation of life and death “In the Bardo” at a gig in Fort Smith, Arkansas, last year.

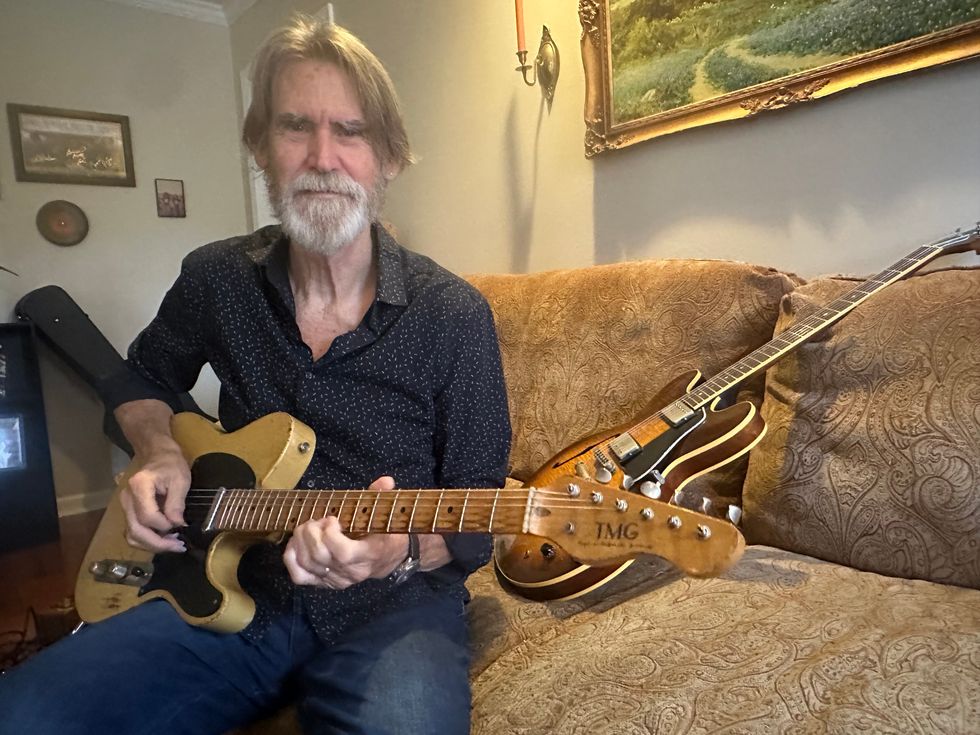

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski