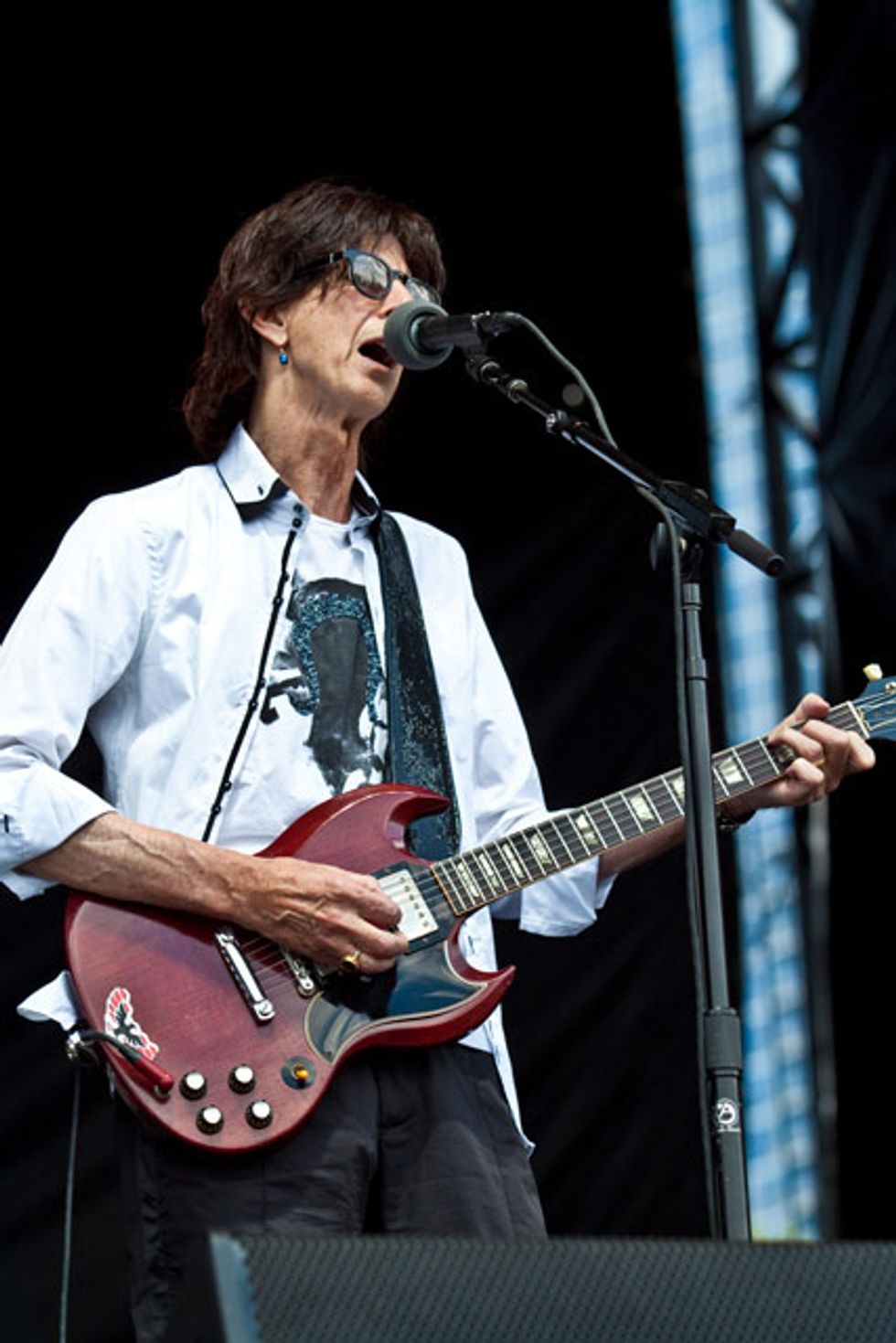

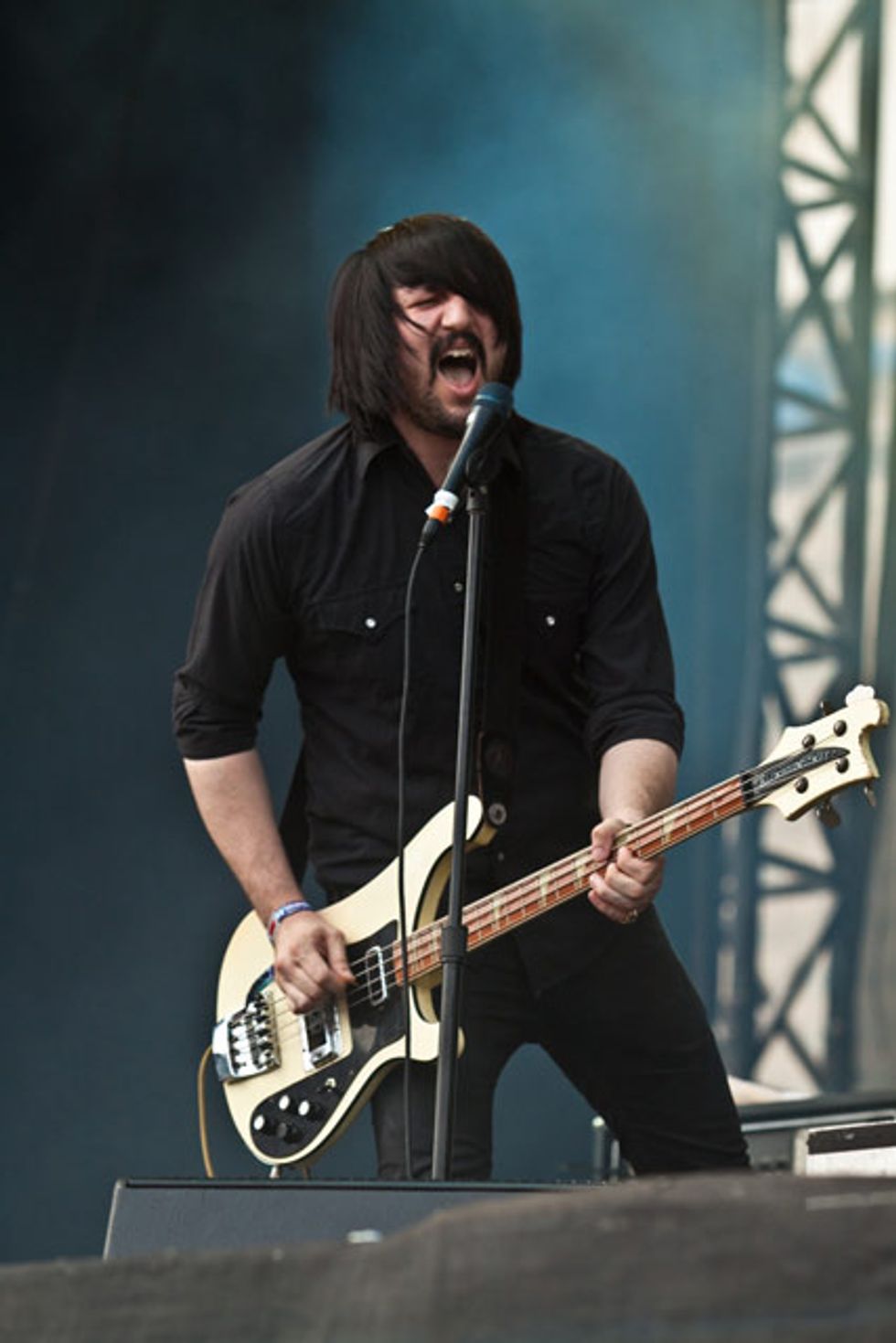

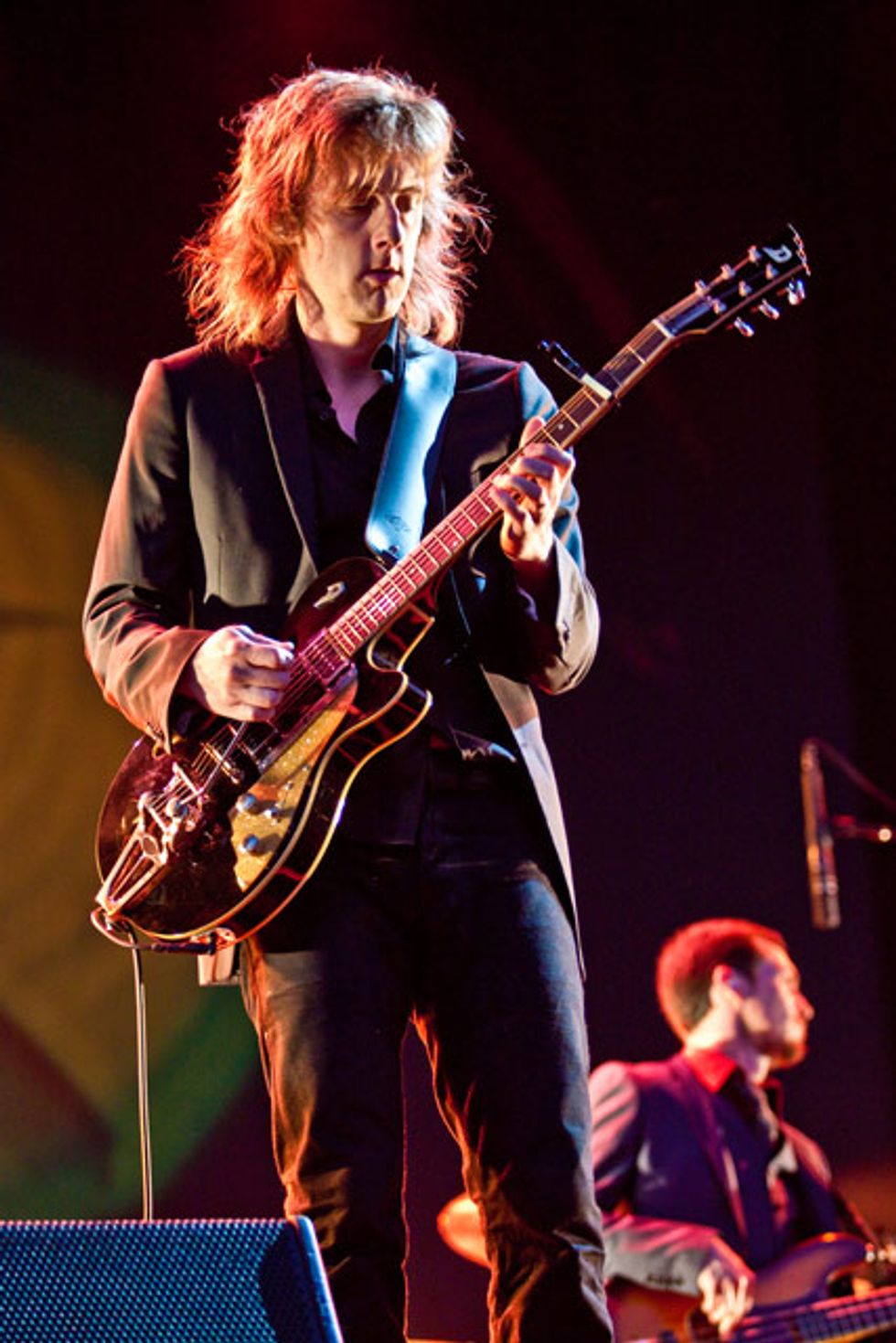

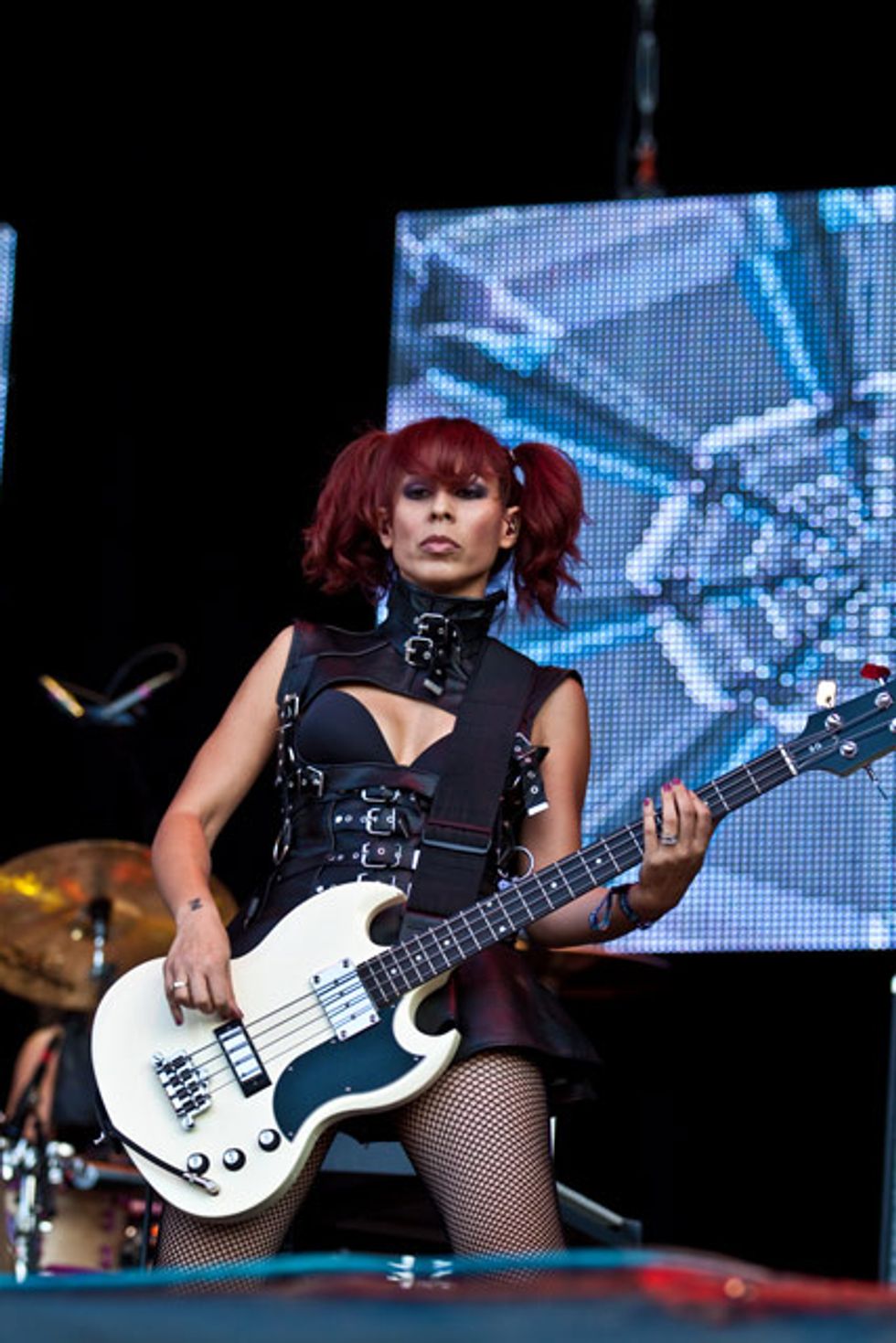

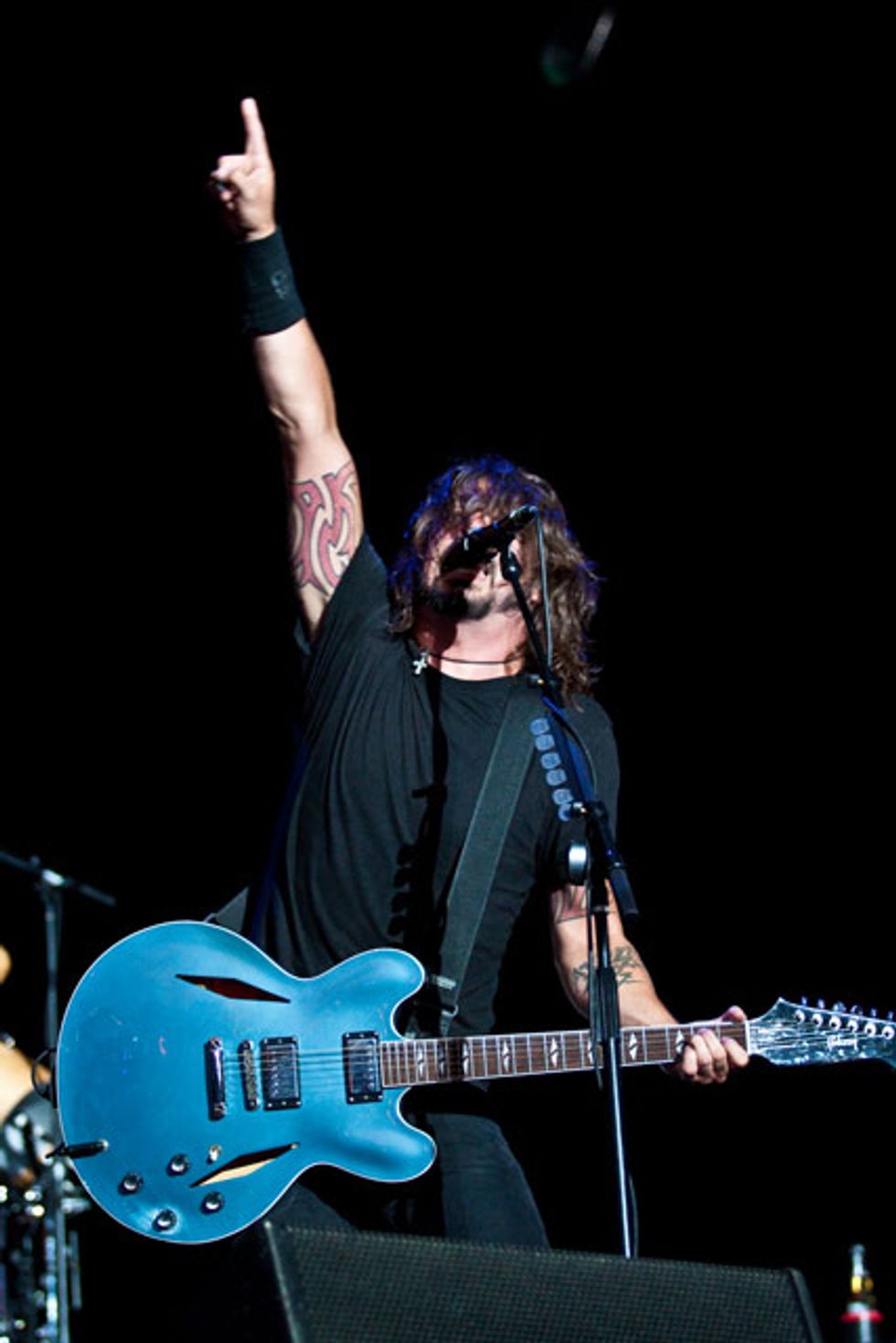

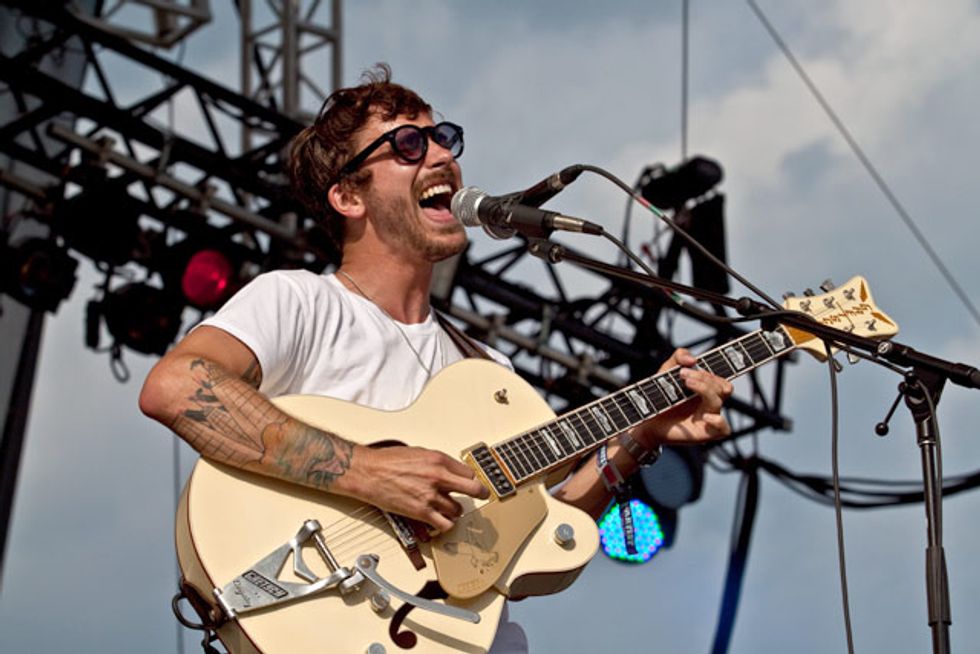

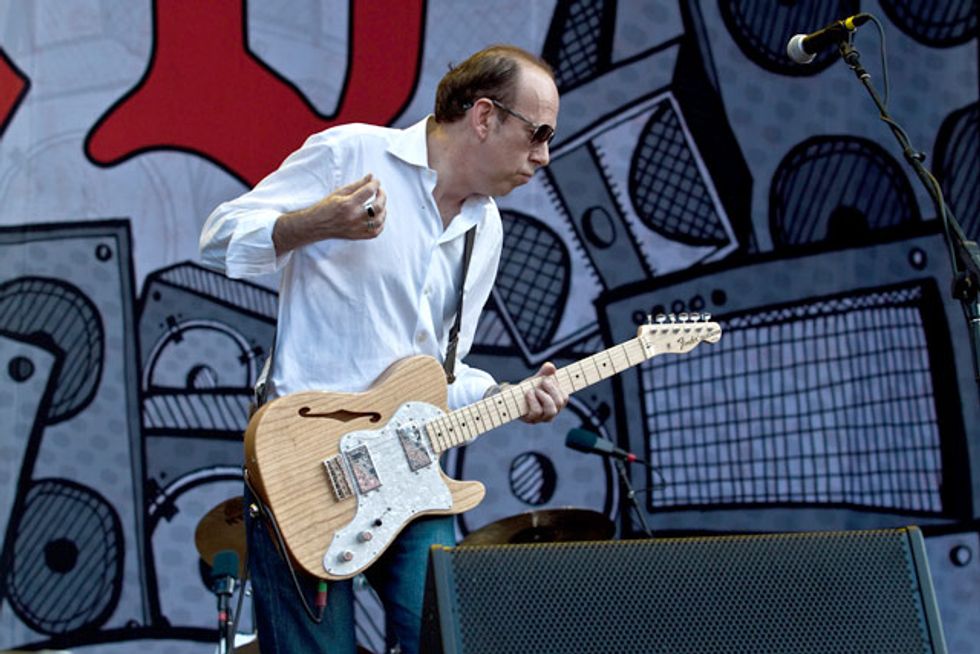

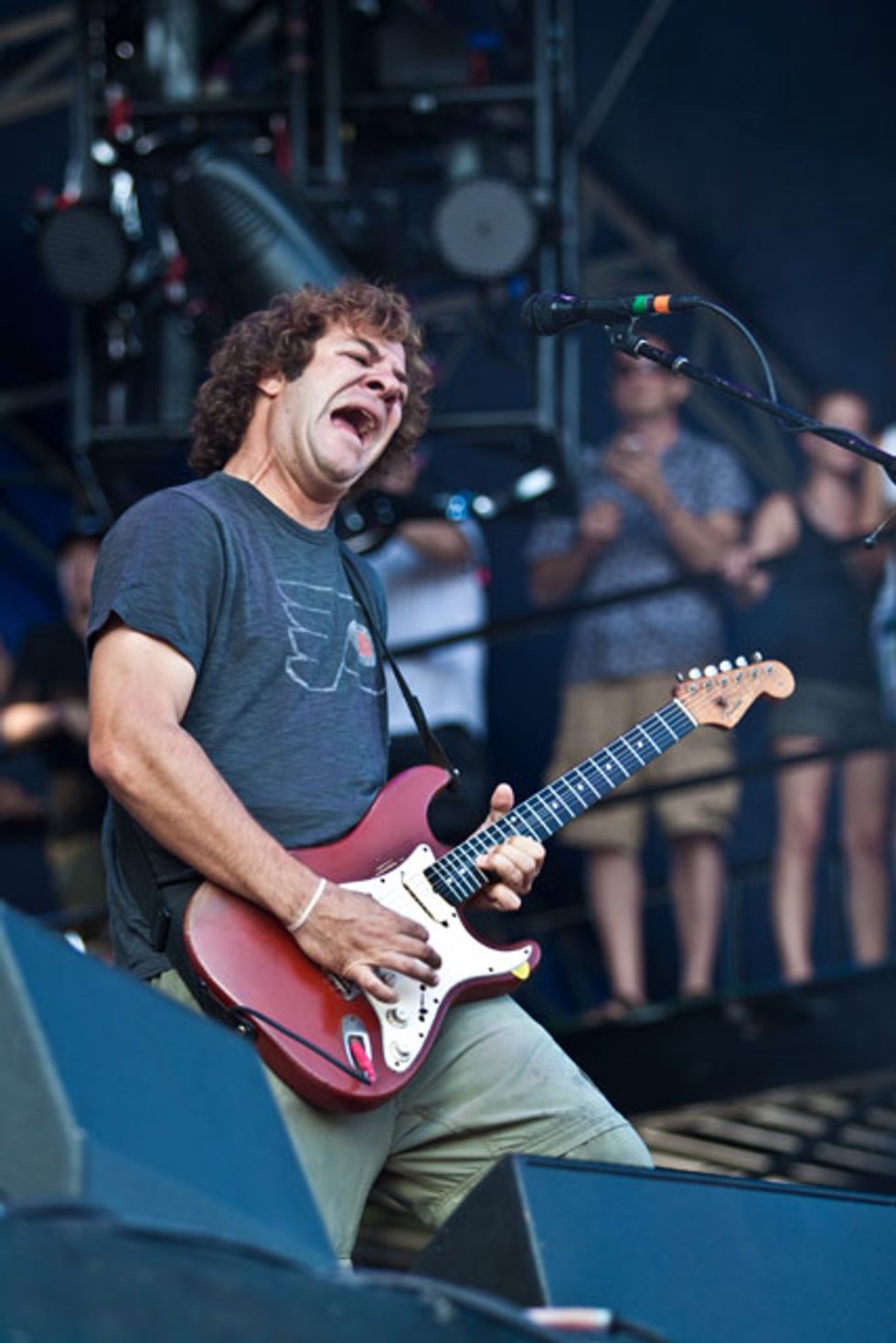

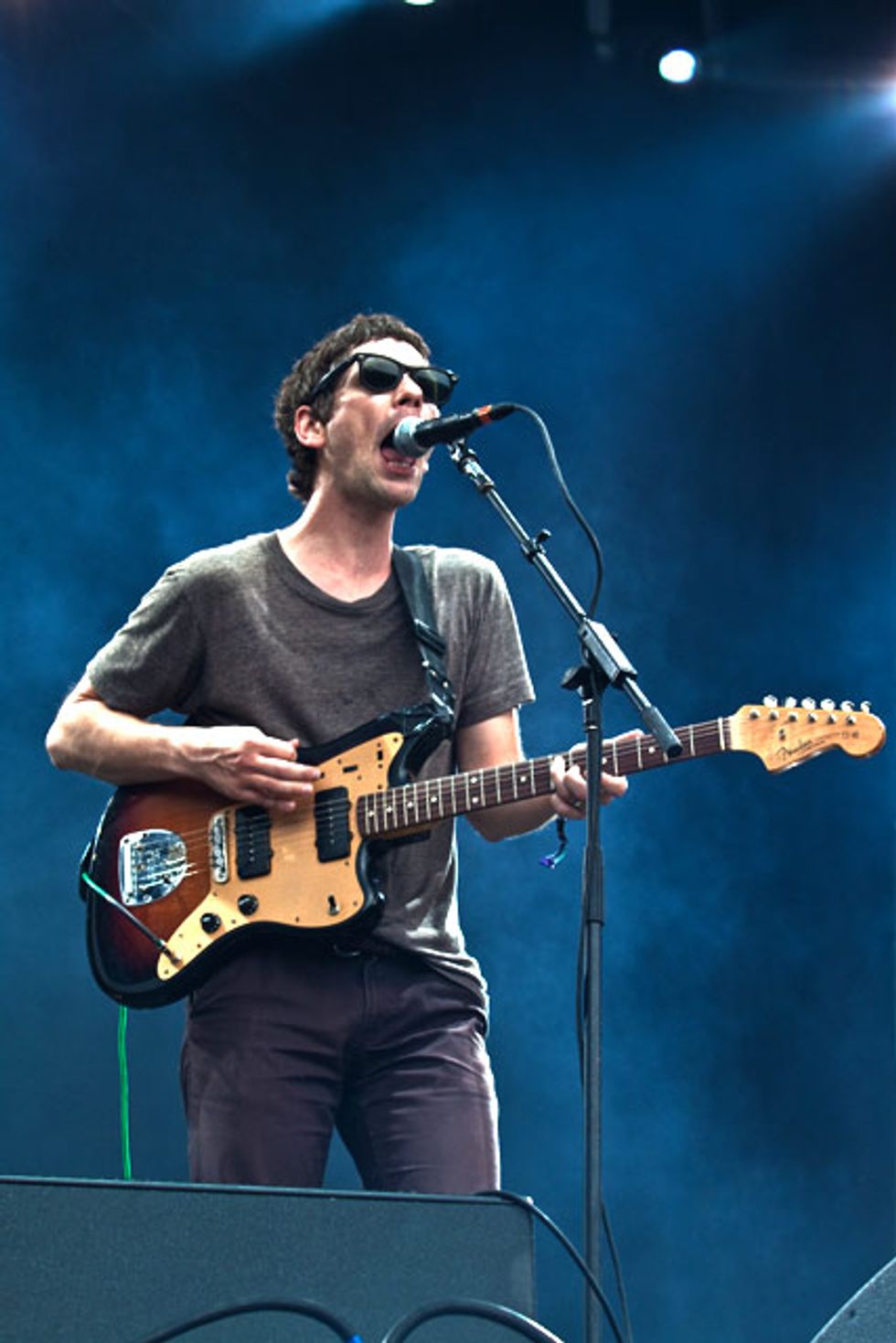

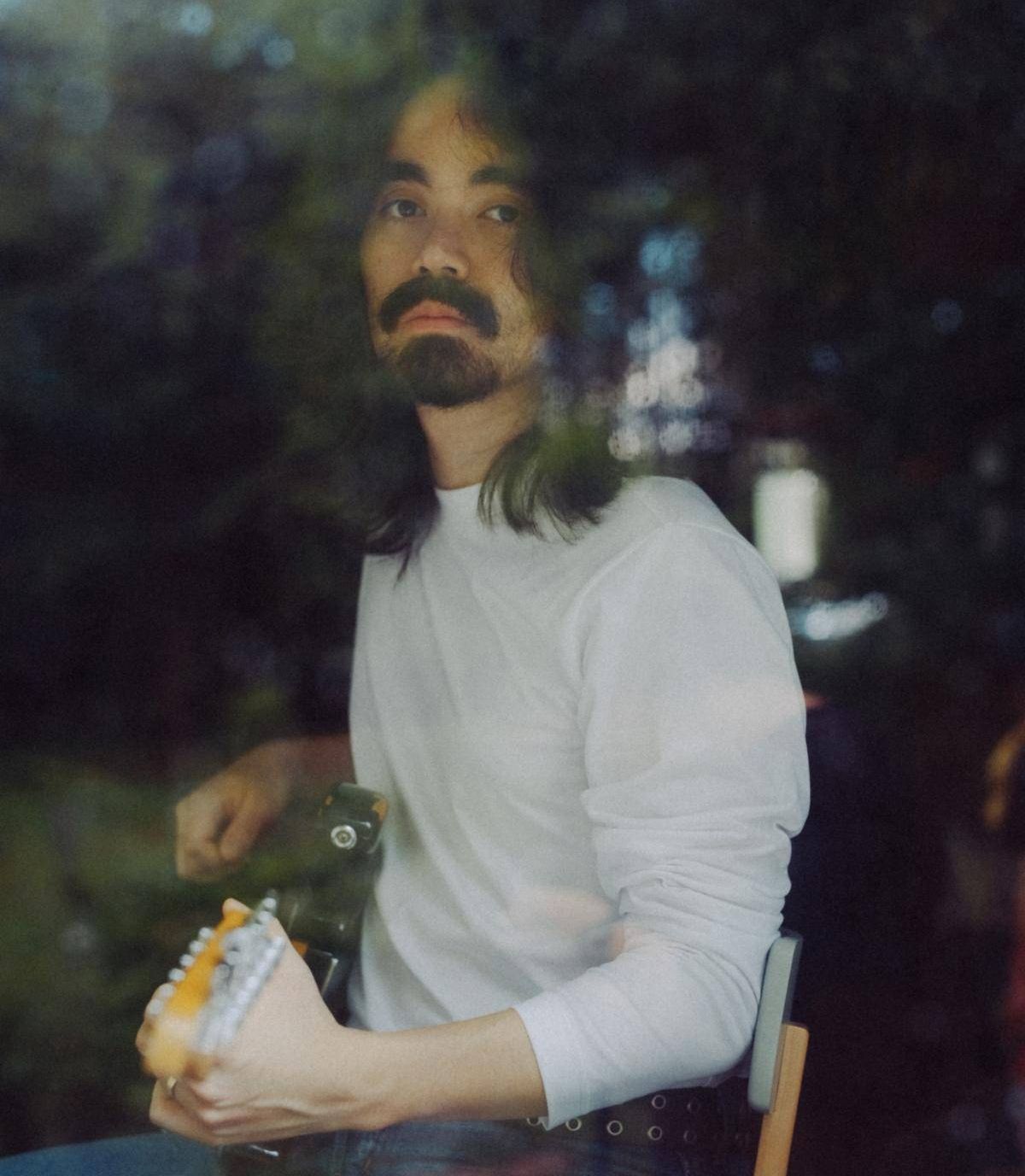

GALLERY: Lollapalooza 2011

A sampling of the bands and guitars that descended upon Chicago''s Grant Park on August 5-7, 2011.

By Chris KiesAug 10, 2011

Chris Kies

Chris Kies has degrees in Journalism and History from the University of Iowa and has been with PG dating back to his days as an intern in 2007. He's now the multimedia manager maintaining the website and social media accounts, coordinating Rig Rundown shoots (also hosting and/or filming them) and occasionally writing an artist feature. Other than that, he enjoys non-guitar-related hobbies.