If you like to make, mod, or mess with your instrument, chances are you’re familiar with StewMac and Allparts. Here, their people tell us how they became the go-to suppliers for DIYers around the world.

It’s easy to forget, but it takes all manner of materials, tools, and know-how to make and maintain a well-loved guitar that’s built to last and plays exactly the way you like it. Pickups, tone knobs, toggle switches, and input jacks. Neck plates, bridges, tailpieces, and saddles. Strap buttons, truss rods, pickguards, string retainers, tuning keys, fret wire, ferrules. Capacitors and circuitry, nuts, and washers, screws and springs. Not to mention the tonewoods and specialized luthier tools used to fashion the body, neck, headstock, and fretboard.

These days, it’s not hard to find the parts and tools that guitarists need to make, repair, or upgrade their instrument. But decades ago, it wasn’t so simple. Before the days of online forums and same-day shipping, guitarists, luthiers, repair techs, and shopkeepers often had to scour the earth for the specific part they were looking for, or make do with an imperfect replacement.

Into that flawed and frustrating market stepped a few enterprising enthusiasts determined to streamline that search for the perfect part. The idea was simple: What if we just sold all of it? Every knick-knack and doodad, all in one place?

In the process, StewMac and Allparts emerged as the leading suppliers of guitar parts and tools, making it possible for nearly anyone to pursue their own quest for the perfect tone.

An acoustic guitar body is formed at StewMac HQ, while DIY words to live by hang in the background.

Photo by Scott Marx

Leading a Community of Luthiers

StewMac’s motto is “making guitars better.” But in the beginning, the brand had almost nothing to do with guitars.

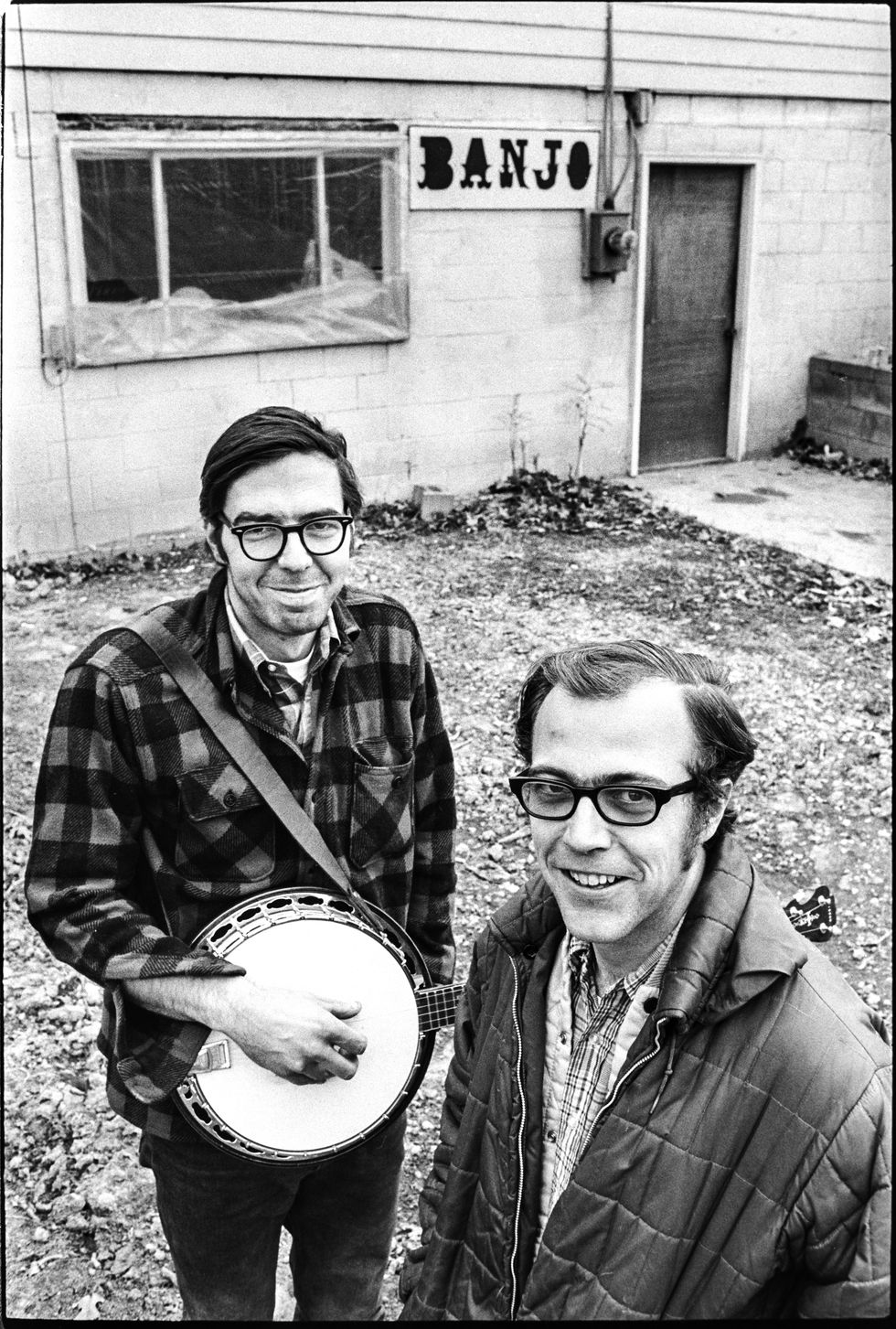

In 1968, Kix Stewart walked into a music store in Athens, Ohio, to repair his banjo. He became friends with the owner, Bill MacDonald, and the two started building their own banjos. Not satisfied with the banjo heads available on the market, they developed their own. Soon, they realized they were making more money selling the individual parts than they were from the banjos themselves. So, Stewart and MacDonald focused on the parts, expanding their business with banjo assembly kits and mandolin components.

The biggest evolution yet came in 1986 with the addition of Dan Erlewine, now one of the most well-known names in lutherie and guitar repair. The company began not only selling guitar parts, but also developing their own specialty tools. Today, the company now known as StewMac is one of the world’s foremost suppliers of tools, parts, and woods for stringed instruments.

Still headquartered in Athens, a small city about 75 miles southeast of Columbus, the company employs just over 100 people at its four-story, 60,000-square-foot warehouse, which houses an inventory of more than 7,000 different products. About 15 percent of that is made, assembled, or modified at StewMac’s facility, while the rest is sourced from third-party suppliers. Elsewhere, StewMac runs their European distribution through the Spanish luthier company Madiner, which carries StewMac products and sources many of the tonewoods they sell.

On the average day, StewMac will ship out at least 800 orders, and during especially busy times—the holiday season, for instance—they can see up to 2,000 orders each day. A team of two dozen pickers works on the warehouse floor, shipping out orders within hours of when they’re received.

“Everybody that works here plays guitar, repairs guitars, builds guitars. It’s not so much a job as it is a calling.”—Brock Poling

As Brock Poling, StewMac’s vice president of marketing, explains, the company has succeeded largely because of its passion for the craft. Poling is a luthier himself, and he was a StewMac customer before he joined the team in the early 2000s.

“We’re not just a company that’s selling you stuff,” says Poling. “Everybody that works here plays guitar, repairs guitars, builds guitars. It’s not so much a job as it is a calling.”

There are several reasons why StewMac has managed to grow from a two-man operation into an international enterprise that’s been in the business for 57 years.

One important factor is their focus on specialty tools. Some of the company’s bestselling products include fretting tools and bending machines that were developed in-house by expert luthiers. This year, two of the hottest products have been the J Edwards Fractal Fret Press, handcrafted by Texas-based luthier Jerame Edwards, and a new acoustic guitar side bending system, designed in-house with input from Charles Fox, the original inventor of the universal side bender.

Where it all began: StewMac founders Creston Stewart (left) and Bill MacDonald.

Photo by Carl Fleischhauer

Among StewMac’s other bestsellers are all-in-one kits that come with everything a beginner needs to complete their own project. The company introduced its acoustic and electric guitar kits in 2017, and a few years later expanded to offer a line of pedal kits, including the highly popular Ghost Drive, a do-it-yourself clone of the Klon Centaur.

“We’ll have people sending pictures of amp kits they’re working on, asking, ‘Where did I go wrong?’ And we’ll help troubleshoot.”—Ally Campbell

But what has really made the difference in the company’s business model, Poling says, is its strategic focus on how-to guides and video tutorials. StewMac has nearly half a million subscribers to its YouTube channel, which offers more than 500 videos about building, repairing, and maintaining guitars.

“This opens a new avenue to give someone a new idea, a new project, a new thing to pursue,” says Poling. “I’ve built our pedal kits. That is a new thing for me. I’ve never really built anything like that before. It’s fun, because not only is it a new project, it’s also a new set of skills.”

In essence, StewMac has fostered a community of users who are regularly looking for ideas for their next project—and conveniently, StewMac has all the parts and tools to bring those projects to life.

“We’ve really tried to look at this as if we are YouTubers first and a brand second,” says Poling. “We don’t sell, we don’t pitch. We want to provide value to the people that are watching these videos. The tools and materials that are in our videos are just cast members in the story.”

Poling says that while a small percentage of the company’s customers are professional builders, the majority are hobbyists. In 2020, when Covid pandemic forced most people to stay at home, StewMac saw an “enormous lift” in sales, Poling says.

There are about 30,000 subscribers to the StewMAX membership, which offers free shipping and returns, discounts, and monthly offers. And if anyone runs into problems, StewMac has plenty of people around to help.

“We don’t just have customer support reps to help with orders—we also have a team of guitar techs who can walk you through projects,” says Ally Campbell, StewMac’s social media manager. “We’ll have people sending pictures of amp kits they’re working on, asking, ‘Where did I go wrong?’ And we’ll help troubleshoot.”

StewMac has tapped into a community constantly on the lookout for the next invention to make guitar work faster, easier, better—or all of the above. That’s also where Allparts shines.

“Recession-Proof”: The Timeless Appeal of DIY

While StewMac was still in its early years peddling banjos, the manager of a music store in Houston had his own idea for a company that would sell the guitar parts he had always had such a hard time finding.

In 1982, Steve Wark started Allparts in his garage, working several part-time jobs to take care of his new family while he cold-called music stores across the country to sell his catalog of 115 hard-to-find products he had sourced from a single Japanese supplier.

“You can’t necessarily count on another Eddie Van Halen and Floyd Rose combination coming along. So, we have to think as players: What would be interesting?”—Dean Herman

Throughout the ’80s, Allparts benefitted from strong sales of metal parts, particularly a bestselling tremolo that was marketed as an alternative to the Floyd Rose, just as that product exploded in popularity thanks to shredders like Eddie Van Halen, Joe Satriani, and Steve Vai.

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique Rodriguez

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique RodriguezNowadays, Allparts sells more than 3,500 items from suppliers in 18 countries, and it fulfills thousands of orders per month. Far removed from Wark’s garage operation, Allparts employs roughly two dozen people at its 13,000-square-foot facility in Houston.

“The company has always been fairly lean. “Everybody here wears a couple of hats,” says Allparts president Dean Herman. “We’re very capable of being able to adapt to whatever the business calls for.”

By 2020, Wark had sold Allparts to the private equity firm Ambina Partners and was planning his retirement. Herman joined the company after 25 years at Fender, where he had worked his way up from junior rep to sales director. First hired as Allparts’ vice president of sales and marketing before being promoted to president a few years later, he was tasked right away with modernizing the company’s e-commerce site, sales and inventory system, and order fulfillment.

Five years later, he reports that results have been positive across the board: a boost in sales, improved logistical efficiency, and a superior customer experience. The company now keeps pricing and inventory more accurate, ships most web orders the same day, and has strengthened its product descriptions to help customers understand each piece of gear and why it could be the right fit for their rig.

Allparts receives a lot of high-volume, lower-priced orders for small, highly specific parts with “evergreen demand,” like jacks, switches, pots, and knobs. But their real bestsellers are the premium, player-oriented aftermarket upgrades, like Leo Quan’s Badass bridges and tuning keys, and the relatively new Certano T-Bender bridge for Telecasters.

Herman is particularly proud of the T-Bender, which was designed by the French craftsman David Certano and further developed in partnership with Allparts. The bridge serves as a simplified alternative to B-Bender and G-Bender bridges, offering players the ability to bend their B or G string up to a full step to get those classic pedal steel sounds. But unlike its predecessors, it doesn’t require any extra drilling or routing to install, and is fully reversible. That makes it way more accessible to players curious to try it out, but who don’t necessarily want to spend hundreds of dollars and permanently retrofit their guitars in the process, Herman says.

“I don't have illusions that [the Certano T-Bender is] ever going to take the place of a Glaser Bender or anything,” he says. “But we just thought an elegant, more-DIY friendly solution would offer players a fun way to dip their toes into that arena, and to take their playing in a different direction without having to modify their instruments.”

That’s exactly the type of new product that Allparts is training its sights on. Herman says he’s excited about the prospect of working with new collaborators who have great ideas that satisfy a niche market—something that’s more challenging today than in previous decades.

“It’s always a good time to be in the parts business.”—Dean Herman

“In the past, it might have been a little easier,” he says. “There was a predominant style of music that you could attach yourself to, and you could come up with an item that catered to a specific crowd. Nowadays, there's a zillion different kinds of players listening to a zillion different kinds of music. So we’re looking for interesting little niches, and that next thing to get excited about. You can’t necessarily count on another Eddie Van Halen and Floyd Rose combination coming along. So, we have to think as players: What would be interesting? What would people find compelling?”

It’s that type of thinking that gave Allparts a leg up in the market when Wark was still getting the company off the ground in the ’80s, and it’s what continues to push the company forward more than 40 years later. To be sure, Herman says, “We have lots of other fun ideas in the works.”

Allparts’ Herman poses at the company’s corporate headquarters in Houston with a Tele fitted with a Certano T-Bender bridge.

Photo by Enrique Rodriguez

Throughout the years, Allparts—much like StewMac—has weathered economic shifts well, relatively speaking. While many American businesses have grappled with the effects of the Trump administration’s new tariffs, both Allparts and StewMac are navigating the situation carefully, and neither reports seeing much of an effect. Similarly to how Brock Poling of StewMac referred to a sizable share of the company’s product line as “recession-proof,” Herman sees opportunities for Allparts to thrive in virtually any economic situation.

“If the economy is great, people are buying guitars and basses, and builders need cool, differentiated parts that offer their customers something new they haven’t seen before,” he says. “But if the economy’s not great, the repair side of the business does better. So in our view, it’s always a good time to be in the parts business. It’s always a good time to be thinking about cool, innovative upgrades for musicians.”