Have you ever grabbed a mallet and bashed away at a gong? If so, regardless of whether it was a tiny tabletop version or a huge one like those favored by hair-band drummers, you no doubt witnessed a continuum of changing frequencies and tones created by its varying vibration patterns. The harder you hit it, the more air it moves, the louder it gets. Those patterns of air movement you hear (and sometimes feel) are directly related to the physical properties of the hammered alloy disc. Naturally, gongs of various shapes and sizes vibrate differently—bigger ones sound deeper, smaller versions sound more shrill. And, of course, a gong player’s playing techniques affect all sorts of audible nuances, too.

These basic principles of sound also apply to a cymbal, a drum, a violin, and basically any musical instrument. But they also apply to a breaking glass, footsteps on gravel, a slamming door, a crying baby, a motorcycle engine, or any of the billions of items generating the sounds we’re exposed to daily. Physics is physics. No matter how sonically different objects may be, they all share a common factor—they create waves in the air that our ears detect as sound. And every little variance in an object’s makeup can alter its resultant sound.

Basic Anatomy and History

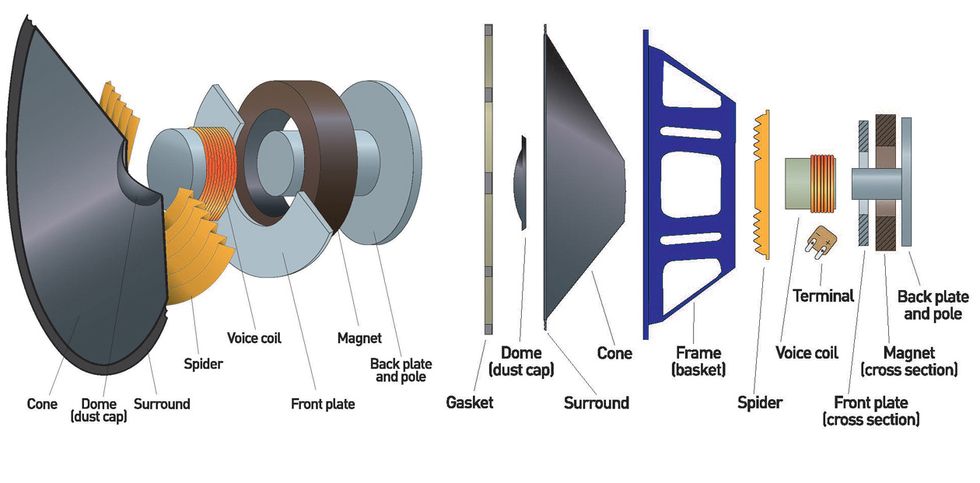

Like any good musical instrument, loudspeakers are designed to broadcast their signals with specific intent. They generate sounds the same way a gong—or anything else—does: by moving air. Unlike a gong, however, a speaker consists of a number of components working together. Every change in design, along with the inherent behavior of the component materials, will alter the characteristics of the sound waves it produces. The waves themselves are ultimately generated by the speaker cone— the funnel-shaped piece of heavy-duty paper you see when looking at an unenclosed speaker. But several other components combine forces to get the cone moving.

The innermost part of the cone is attached to a voice coil—the part that vibrates the cone. Appropriately named, the voice coil typically consists of a coil of copper wire. If you buy into the idea that when you play an electric guitar, you are also playing the amplifier—and, ultimately, the speaker—then the voice coil is the first speaker component you’re playing. The positive and negative wire-connection leads on the back of the speaker are directly connected to the voice-coil windings.

Despite its importance in the signal chain, the voice coil isn’t easy to actually lay eyes on. From a front view, it’s located behind a little domed protective dust cap at the center of the speaker, and from the sides the coil is surrounded by a donut-shaped magnet. The coil is fragile, but it’s well protected.

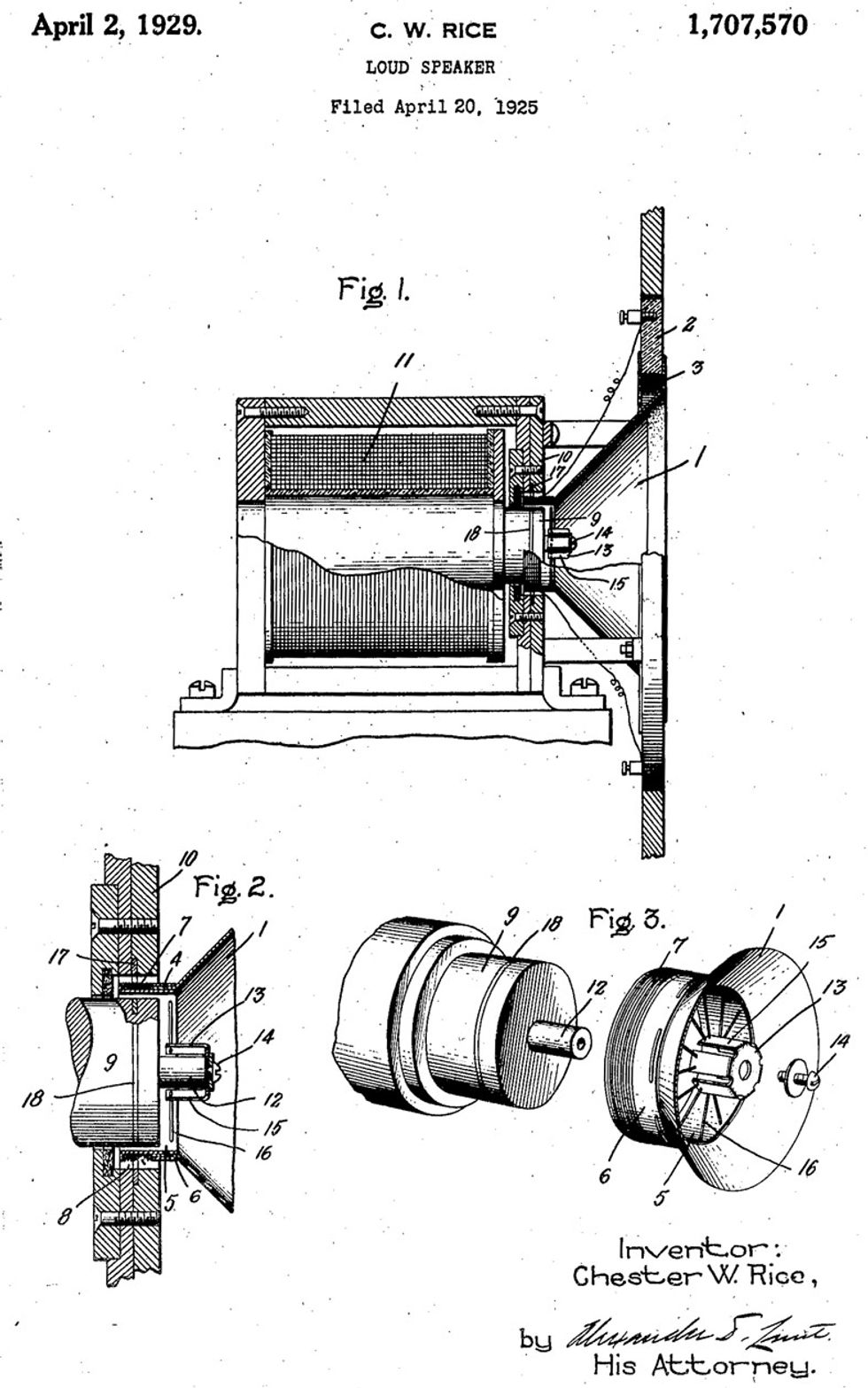

Filed with the U.S. patent office on April 20, 1925, Chester Williams Rice and Edward Washburn Kellogg’s music-optimized loudspeaker design was eventually released in 1926 by RCA as the Radiola Loudspeaker #104.

We can trace the origins of the voice coil to Hans Christian Ørsted, a Danish physicist and chemist who, in 1820, noticed that compass needles act differently around electricity. He soon figured out that when electricity flows through a wire, magnetic fields are created. Ørsted was a curious guy—in 1825 he was also the first person to produce aluminum. However, he never got the chance to hear a speaker.

Ninety years after Ørsted’s discovery, two Americans—Peter L. Jensen (also of Danish descent) and Edwin S. Pridham—created a public-address-system speaker that used a moving coil. Subsequently, one milestone in early loudspeaker history was when President Woodrow Wilson used a PA to address a crowd in 1919. In 1921, Chester Williams Rice and Edward Washburn Kellogg, respectively with General Electric and AT&T, worked to refine the idea with a focus on higher fidelity for music reproduction. They applied for a patent titled “loud speaker,” culminating in RCA’s release of the Radiola Loudspeaker #104 in 1926.

Why does RCA’s iconic early logo depict a dog up close to a mechanically amplified early phonograph? Perhaps because they were famously volume challenged prior to the invention of the loudspeaker.

History buffs are no doubt looking at the timeline here and rightfully thinking that we’ve overlooked some pretty important stuff. After all, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1875, and Thomas Edison’s phonograph followed two years after that—and obviously both required some sort of amplification device predating Jensen and Pridham’s and Rice and Kellogg’s loudspeakers.

Bell’s early telephones managed to make intelligible sounds, but the earliest versions had little or no fidelity. And Rice and Kellogg’s design was a dramatic improvement over the horns Edison, Motorola, and the Victor Talking Machine Company (makers of the Victrola) used to mechanically amplify recordings on early phonographs. There’s a reason the original RCA “His Master’s Voice” logo shows the dog sitting right next to the horn on the hand-cranked player—volume was severely lacking. The loudspeaker changed everything.

Now closing in on its 100-year anniversary, Rice and Kellogg’s loudspeaker design is essentially unchanged from the speakers we use today. There have been countless updates in construction and materials used since the 1920s, all of which improved not just fidelity, but also power handling. But the basic configuration remains.

The basic anatomy of a conventional loudspeaker.

Guitar (and Bass) Speakers vs. Playback Speakers

Typically, speakers designed for listening to recorded music have one primary goal: to produce an even response across a wide frequency spectrum, at varying volume levels. In other words, quality audio speakers aim to have as flat of an EQ response as possible in order to accurately reproduce the sound the artists and engineers intended you to hear, without coloring it in any way. An audio speaker also, of course, should be devoid of distortion. Audiophiles want unadulterated sound.

On the other hand, although identical in basic construction, speakers for guitar amps are designed from a very different point of view. Guitar speakers are purposely intended to add character. As Anthony Lucas, design engineer at Eminence puts it, “Guitar speakers are tone creators, whereas other speakers are sound reproducers.” Each component—the cone, the surround (which attaches the cone to the frame), the spider (which holds the voice coil in place), the voice coil, and the magnet—affects the speaker’s tonal character in some unique way. All of these parts are, therefore, in a speaker designer’s toy box. That said, speaker design is admittedly something of a black art, because every part also has its own set of idiosyncrasies, advantages, and potential challenges. For manufacturers, the result of design and component variations always comes down to a final audition.

As a player, if your ultimate goal is to replicate the sound of one of your favorite guitarists, something you heard in a live performance or a recording, you may be faced with a challenge. “Changing speakers can change your tone more drastically than anything else next to a pedal or the guitar you use,” says Orin Portnoy, vice president of marketing and sales at Jensen Loudspeakers. He adds, “The main question [I get] is how do I get speakers to sound like so-and-so?” But speakers are just one link in a chain of factors that starts with your fingers and ends with your guitar notes ringing out to the crowd. The nice thing about speakers, however, is that they can be swapped out much more readily than, say, pickups. And they’re certainly more affordable than most new instruments or complete amps you’re likely to consider as tone game-changers. You can simply run your amp through a different cabinet or, with just a little work, remove your existing speaker and replace it with something different. You simply need to make sure the new speaker’s impedance and power rating jive with what’s coming out of your amp. We’ll talk about both of these more shortly.

This may seem obvious, but perhaps the best way to find a speaker that suits your style is simply to consider its frequency-reproduction traits. “A lot of people think ‘genre’ [when considering new speakers]—but I don’t like grouping speakers by genre,” says Eminence’s Anthony Lucas. “I don’t like pigeonholing speakers that way, because even a blues player and a metal player may want the same qualities in their tone. They may both want more low end or more warmth or whatever the description may be. I like to shoot for the tonal characteristics a guitarist wants.”

Lucas also has some poignant thoughts on the previously mentioned idea of matching the speaker’s power rating to the amp’s power output—something he says is a common point of misunderstanding. A speaker’s wattage rating does not need to match the amp’s power output. The speaker rating should,of course, be equal to or greater than the amp’s output in order to prevent overheating and burning the speaker out. But a speaker with a way higher wattage rating than the amp’s output section can work perfectly fine, too. “Guitarists often think they shouldn’t use a higher-watt speaker with a 5-watt amp, for instance,” says Lucas, “but I may recommend a 150-watt speaker for a 5-watt amp if the speaker has the right tone. ‘But my little amp won’t push that speaker!’ Sure it will!”

Speakers don’t need a lot of power to make them loud, so don’t make the mistake of ruling out a design with a higher power rating than your amp. On the flip side, you may very well be happy with a close power match, too. The choice should be determined by the sound characteristics you’re looking for.

Things to Consider When Shopping and Swapping

Before jumping into the big, exciting world of speaker swapping, it’s important to make sure you understand the relevant nomenclature and terminology. Let’s dive into the basics (as well as two or three more obscure specs that some high-end speaker manufacturers allow you to customize).

Size: Most guitar amps use 10" or 12" speakers, although you’ll also find the occasional 15". A 10" can be punchier and tighter sounding, while a 12" usually delivers more bass, and a 15" has even more oomph—though with some possible sacrifices in clarity or treble response. Low-wattage guitar amps tend to be stocked with 8" speakers, which can sound surprisingly great. Bigger isn’t automatically better. Bass amps, meanwhile, typically use 10" speakers, or maybe a 15" for a sub. But 12" speakers are also becoming increasingly popular for bassists, too. All this said, considering all the variables that go into speaker design, these descriptions of size-related characteristics are simply generalizations. Speakers will vary greatly. This may be good news, because realistically your choice of speaker size may be based on the size that will fit into your amp or cabinet. Even so, you’ll still have wide variations in sound to choose from.

Magnet alloys: A speaker’s magnet material may be alnico, ceramic, or neodymium. Alnico (aluminum, nickel, and cobalt) was the magnet used in early (pre-1960s) speakers, which is no doubt why Portnoy says, “It’s generally associated with vintage tones, having a high frequency bump.” Alnico is also a slower-moving magnet. What exactly does that mean? Well, thermally, different magnet materials behave differently. Alnico has a relatively low thermal limit, and if you push it hard the heat causes temporary demagnetization—although its magnetic-flux properties return upon cooling. The demagnetization that happens with alnico-magnet speakers is enough to cause a compressor-like effect where your loudest notes become fatter and a little less loud.

Ceramic magnets, on the other hand, are faster. First used in the 1960s to keep speaker prices down in the face of increasing cobalt prices, ceramic magnets have a stronger magnetic field, resulting in a smaller, lighter magnet that takes the heat better than alnico. With a ceramic magnet, louder notes get louder rather than compress, which many players find to be a more dynamic and expressive response.

Neodymium is the newest of the three materials. It's slow, reacting much like alnico, considerably lighter in weight, and great at handling lots of power. Therefore, it’s a third option to consider.

Here you can see the concentrically corrugated spider attached to the apex of the speaker cone.

Impedance: As a general rule, in order to operate properly and avoid risk of damage to itself and/or your amp, a speaker should have an impedance rating that matches your amp’s output-impedance rating (the number printed next to the speaker jack, usually 4, 8, or 16 ohms, sometimes 2 ohms for bass amps)—although there are some somewhat complicated exceptions beyond the scope of this introductory article. That said, keep in mind that wiring two or more speakers together changes the impedance load on the amp itself: For example, two 8-ohm speakers wired in parallel will create a 4-ohm load, and two 8-ohm speakers wired in series become a 16-ohm load.

Power rating: A speaker’s power-handling ability is measured in watts, and it’s a specification that’s often misunderstood or misinterpreted. The rating indicates the wattage a speaker can endure when tested—not with a guitar signal, but with a standard pink-noise signal called EIA 426A—before experiencing mechanical failure though overheating or breakage of one or more of its components. When amplifying a guitar signal, a speaker pushed to the upper limits of its power rating will not necessarily sound good—but it won’t mechanically fail unless that limit is exceeded. In addition, if one speaker’s wattage rating is higher than another’s, that doesn’t necessarily indicate it will be louder. A speaker’s volume capacity is indicated by its efficiency rating: a measure of the speaker’s loudness with a given input signal. However, this is yet another rabbit hole beyond the scope of our basic discussion. For our intents here, the loudness of any given amp and speaker configuration is determined by a number of factors, including the type, efficiency, and wattage of your amp’s power section—which is, after all, what’s driving the speaker.

One myth commonly heard by Lucas at Eminence concerns the relationship between wattage rating and “breakup”—i.e., overdrive or distortion. “Everyone thinks that if you have a high-power speaker, it won’t break up, or that a low-rated speaker will break up too much. That may be true in many cases, but power ratings and breakup are not directly related.” Many factors determine when and how a speaker’s sound will break up. And driving a speaker until it distorts will sound better for some speakers than others. For this reason, most manufacturers proffer layman’s-terms descriptions of a speaker’s general sound to supplement the electrical specifications.

While speakers of different makes and builds have varying efficiency ratings, on the whole, traditional speaker designs of the sort discussed here are dismally inefficient: The ratio of “power out” over “power in” is less than 5 percent. Speakers produce heat more than they produce sound.

Cone design: Perhaps the most influential factor in speaker breakup is the thickness and density of the cone material. Since the beginning of speaker history, paper has been the primary material used for cones. A cone made from a lighter, thinner paper will break up more readily than a cone made from heavier, denser paper. The choice of material has other implications as well. For example, a more flexible paper will be better at conveying low frequencies, while a stiffer paper is typically more suitable for treble frequencies.

When speaker shopping, you may notice that some speakers feature cones that are smooth, while others are ribbed. Ribbed cones started appearing in the late 1940s and early 1950s as a way to gain the advantages of stiffer cone paper without adding mass, which would have an effect on tone. It was a simple solution to accommodate loud playing while avoiding distortion. Because of this, all else being equal, a smooth cone will distort more readily than a ribbed one.

The spider: Looking at a speaker assembly, you may be inclined to think the spider (the concentrically corrugated part that holds the voice coil in place and allows it to move freely) isn’t designed to influence the tone. But spiders can be made stiffer or looser in order to affect upper-midrange response from around 800 to 1,000 Hz.

The surround: Yes, even the part of the speaker that connects the outer rim of the cone to the “hoop” of the speaker’s metal frame affects tones, mostly in the higher range. Generally, stiffer surrounds are more conducive to emitting treble frequencies. Common surround materials include corrugated cloth or paper. Also, while the surround’s design is intended to allow free movement of the cone, the surround itself may have a resonant frequency, increasing or decreasing specific frequencies and affecting tone. In some cases, an unwanted “edge yowl” can occur when the energy from the surround’s resonation transfers back to the cone.

Embarking on the Adventure

Shopping for the perfect speaker isn’t easy—it’s certainly more complicated than buying, say, a new instrument or amp. However, as with guitars and pickup swapping, many times the right replacement speaker can make that final bit of difference between liking an amp and finding it absolutely indispensible. In some cases, the right speaker swap can even make you fall in love with an amp you didn’t like at all and were considering hocking.

The ideal approach to speaker shopping has many facets: researching your favorite players’ go-to speakers, reading reviews and forum posts from players who seem to have gear and musical tastes similar to your own, consulting with trusted and experienced players who get what you’re going for, listening to sound samples, watching demo videos, and, of course, confirming that the technical specifications of speakers in the narrowed field comport with your amp. In the end, though, your ears are always going to be the final judge. You’ll never know for sure if you like a speaker unless you audition it in person, using your own guitar, amp, and pedals, and spending a reasonable amount of time playing at the sorts of volumes you normally play at.

Given the breadth of offerings on the market, chances are you won’t get to audition most of the speakers that could be a good match for you. But keep in mind that doing your homework and then making a leap-of-faith purchase has just as much potential to transform your sound as a new pedal—and a new speaker is often easier to incorporate into your signal chain than figuring out where to insert a new stompbox on a crowded board. The other good news is that, just as with pedals, there are so many great guitar and bass speakers to choose from that there is no single “right choice”—there are likely several speakers that would be a wonderful match for your needs.

On the other hand, going gong shopping would be much easier.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)