Photos by Tanya Alexis

Immaculately painted bodies, chromed accents, and rusty edges that are both signs of loving wear and tear and marks of character—all are found on two things James Trussart treasures: classic cars and the guitars and basses he creates. The love goes so deep that he approaches each instrument as if he were building a fine automobile, even adorning his headstocks with a logo that’s reminiscent of Cadillac’s script font.

This penchant for “old stuff ” goes much deeper than aesthetics. It harkens back to before mass production and cheap labor—a time when craftsmanship meant handmade, heartfelt quality. With his rugged-yet-refined metalwork, Trussart reminds us of a longstanding adage that beauty is often fraught with so-called imperfections. He has, after all, made a career out of what he calls “some very happy mistakes.”

But these so-called mistakes have led to a line of custom guitars and basses that have caught the attention of notable players in every genre. Trussart’s client list includes the biggest names in the biz—Billy Gibbons, Bob Dylan, Joe Perry, Eric Clapton, James Hetfield, Bob Weir, Jack White, and many, many more. That’s because there’s not any guitar quite like a Trussart.

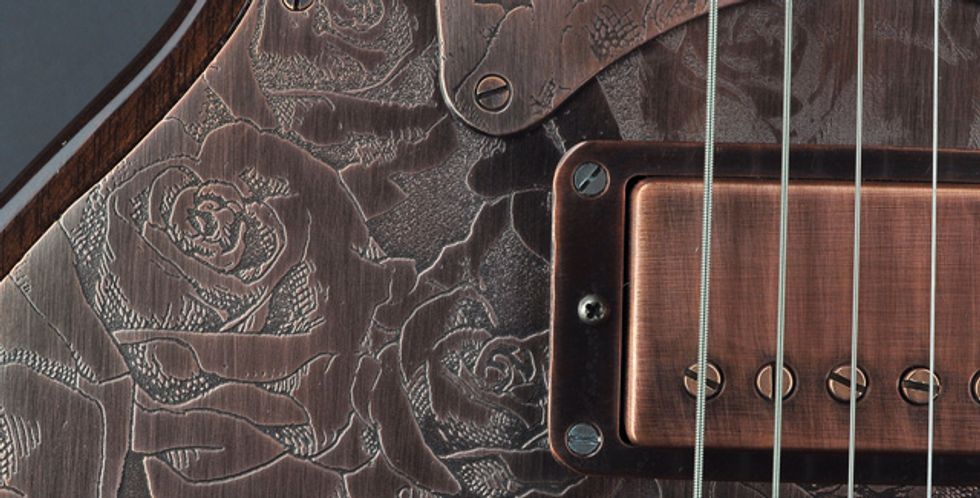

This James Trussart Antique Copper

Roses SteelTop model is equipped

with a B5 Bigsby and features a rose-engraved

top, pickguard, and headcap.

Other features include a mahogany neck

and body, rosewood fretboard, cream

binding, and Arcane Inc. humbuckers.

With a style so strong, one might think the luthier was born into a family of artists. “Not at all,” he says without hesitation. “That was probably why there was a call for that—a need.” While Trussart’s family may not have influenced his path to lutherie, their geographical location did. Trussart was born in 1950 to horse-breeding farmers in the northeastern French village of Nancy, not far from Mirecourt—a region famous for its violins and other stringed instruments. Guitars were rarely seen and extremely hard to come by, but the Trussart farm was near a U.S. Air Force base, and the young Trussart was introduced to American music through military bands. He picked up his first guitar around age 16 and started building dulcimers just a year or two later.

Being a guitar fan in the ’60s, Trussart was, of course, greatly influenced by the bands coming out of Britain at the time. He spent the summer of ’69 in England, where he had the chance to witness early pop festivals. And it all fed into his love for all things 6-string. His tinkering with instruments was a natural evolution that eventually led him to repairing guitars and building his own instruments, with a lot of trial and error along the way. In fact, the self-taught craftsman says he’s never done anything else for a living, nor worked for anyone else.

From France to

Louisiana … and Back

Early in Trussart’s career, it was

hard to find workspace—he

moved at least 10 times while trying

to establish himself in France.

On the other hand, he says those

were still simpler times.

“My rent was $50. I could sell a dulcimer for $100, and if you sold one a week, you were good,” he remembers with a laugh. When asked about mentors, he says simply: “My mentors were the guitars that I was repairing. I was taking them apart and trying to get the right replacement, learning from everything I could. But mostly books. It was a long learning process.”

Trussart was already dabbling with guitar building when he moved to Lafayette, Louisiana, for a year in 1980. He quickly felt at home in Lafayette’s music community and decided to pick up the fiddle and learn to play Cajun songs.

“As a French-born, French-speaking person, I thought that was something really exciting,” he says. “That was very inspiring, and you can see that in my work with all the reptilian, alligator patterns.”

He built strong ties to the community, befriending players like Zachary Richard (with whom he toured as a fiddler), Sonny Landreth, and C.C. Adcock. “I’m still close to those guys. I just went to the Voodoo festival [in New Orleans] a couple of weeks ago because a lot of my friends were playing.”

After his yearlong stint in bayou country, Trussart returned to Paris inspired. He spent the rest of the ’80s repairing instruments and conducting “crazy experiments” with different building materials. His first metal instrument wasn’t a guitar but a violin, because that was what he was playing himself at the time.

James Trussart

with one of his

latest designs,

the Rust O Matic

Cream Fleur de Lys

SteelCaster, which

he had just finished

at press time

for NAMM 2013.

James Trussart

with one of his

latest designs,

the Rust O Matic

Cream Fleur de Lys

SteelCaster, which

he had just finished

at press time

for NAMM 2013.

“I felt I could get a different tone out of it,” he says of delving into metalworking. “My limits were such that I was thinking, ‘Even if I play, like, three chords or just blues stuff, that would be interesting to come up with something that sounds different.’ So I did.”

The result of Trussart’s first attempt at a metal instrument was way too heavy, but it was that all-important first step. From there, he was on a quest for something lighter and more playable.

He then tried his hand at gold-plated and chromed guitars, and for his first foray into using steel on a guitar he used stainless steel. “I was attracted by that kind of slick, shiny look. But then my tastes changed as I was collecting guitars.” He explains, “I’m a vintage collector. For 15 years I had a shop where I was building custom orders of all kind of styles—6-string basses, 5-string basses—building the instrument from A to Z, shaping the necks, shaping the bodies, importing wood. I had a huge carpentry shop, too, and I was buying chunks of wenge.”

Trussart then moved away from stainless but stayed with steel, first trying recessed metal tops on chambered wood bodies. “Then I extended into all different kind of models, so I had to create all different kinds of names. I had to create families of instruments.” The Trussart family tree grew rapidly and now includes the SteelCaster, SteelDeville, SteelCaster Bass, SteelPhonic, SteelResoGator, Steel O Matic, SteelTopCaster, SteelTop, Steel TeleMaster, SteelMaster, and the Steel X. And both new and die-hard Trussart fans will be happy to hear there are a few more buns in the oven.

Globalized Guitars

James Trussart’s designs are very much intertwined with his life experiences and personal ties. His love for classic cars bleeds into his overall approach to metal instruments, and his love for Cajun music and culture informs his use of alligator skin patterns and shapes like the fleur-de-lis. Though it may seem subtle or even undetectable to the average player ogling his guitars and basses, geography is actually a recurring theme throughout his work. Trussart often travels for inspiration and then expresses what he sees through graphics, textures, and colors.

The story behind the African Steel- Top began when Trussart traveled to the world’s second-most-populous continent and was blown away by the designs of tribal artisans there. He gave different shapes and contours of metal to several African artists who were working on jewelry and asked them to engrave the parts however they pleased. He returned to America with 10 unique parts and tops. “They work with very primitive tools, and that’s what makes the whole thing interesting,” he says. “I came back and did a little modification of that—like, maybe there was a scratch by mistake or something.” He eventually arrived at a final design that he transferred to a guitar model.

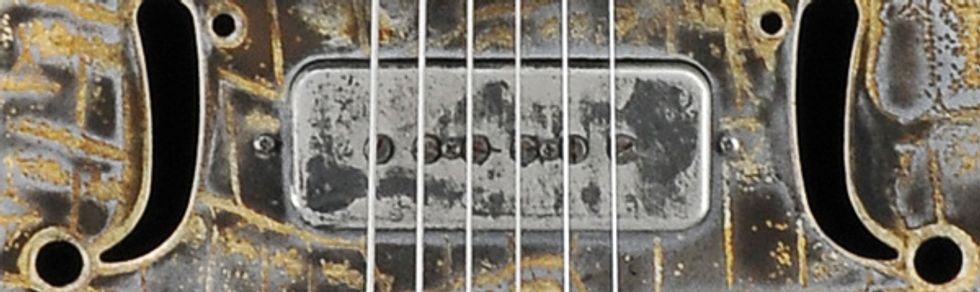

The Antique Silver African SteelTop model pictured here is owned by “Captain” Kirk Douglas from the Roots. “He’s a great friend of mine,” says Trussart, “In fact, I’m making another guitar for him.” Several African musicians also play African-engraved Trussart guitars, including a blind duo from Somalia called Amadou & Mariam that has opened up for Coldplay.

Similar inspiration came when trips to Asia and Jamaica inspired Trussart to create the Chinese Coin SteelTop and Rastafari SteelCaster, respectively. “I came back with all the Jamaican colors [in my mind] and ended up making guitars and a bass for Robbie Shakespeare and my other favorite reggae musicians, like Ziggy Marley.”

Old Meets New

In an effort to meld the best

of old and new, Trussart’s

approach has always been

about fine-tuning and

modification than reinventing

the wheel. He worked on all

kinds of Gibson and Fender

models that customers brought

in with broken headstocks or

frets or pickups that needed

to be fixed or replaced. In the

process, he figured out how

things were built and was thus

well equipped to expand upon

it.

“It’s like you cover your favorite songs, and then you come up with your own songs,” Trussart says. “Look at all the greatest artists—the Stones covered Chuck Berry, and the Beatles, too.”

With their intricately adorned and aged metal parts, Trussart guitars can be spotted a mile away, but the inner electrical workings and overall composition are just as integral as the ornamental details. According to the luthier, one thing that sets him apart from other builders of metal-bodied guitars is his use of a punch press (a machine that cuts and forms metal). Trussart says it improves rigidity in the metal and helps the guitars stay in tune better. He also makes models with chambered wood bodies and metal casings, but his trademark instruments feature a body made entirely of metal. Within this category, he offers choices of perforated top and back (which yields a see-through effect) or half-perforated metal plating with, say, a perforated top and solid back. All of these combinations provide different tones, and Trussart says one of the biggest factors they affect is sustain.

The SteelPhonic model, for example, is designed to capture the ringing, metallic tones of a classic resonator, but with a twist. It’s built around a metal candy box attached to a transducer pickup, providing a unique flavor that can be blended with two magnetic pickups to create sounds Trussart says, “no other guitar can produce.” It is a true monostereo instrument that can be played through a Y-chord and two speaker systems—say, an acoustic amp and an electric amp, or an electric amp for the magnetic pickups and a PA for the transducer pickup.

“It doesn’t really sound like a resonator guitar, and it doesn’t really sound like an acoustic guitar—it’s like a mix of all that on one side. On the other side, you have two humbuckers, and it sounds like an old Firebird. So when you tune that guitar to open D, for example, you have something really, really amazing and special.” (To hear it, visit YouTube and search for “Freddy Koella playing a James Trussart Steelphonic.”)

Another interesting deviation is the Steel X, which was designed in tandem with Metallica’s James Hetfield—who owns five Trussarts. It features a Gibson Explorer-inspired look with a metal top that’s recessed into the body in the same manner as all Trussart headstock plates. “The combination of metal on each side of the instrument is a great sustaining process.”

The SteelResoGator model features several Trussart trademarks, including perforated metal and

gator-patterned engravings.

Trussart has gotten pretty good at managing the weight problem encountered with his early work. His instruments now range from 6.8 to 9.5 pounds, with the heaviest being the larger and longer-scaled basses. “You can get lighter than that, but then you might have problems with staying in tune—and you get a different tone,” Trussart insists. “I went through all of [those considerations] along the way.”

From the early ’80s through 1999, Trussart developed his unique take on guitars, and by the time he moved to L.A. in 2000, he already had the support of clients like Gibbons, Taj Mahal, and Clapton. That encouragement from big-name musicians was a big factor, but he still felt he wasn’t quite understood in the larger scheme of things.

“Thirty years ago, people were joking about what I was doing. They were kind of sarcastic, like ‘Pffft!.’ Because it was different. So it took me awhile to get some recognition.”

Trussart (right) says builder William Raynaud (left) is like a son.

Like a Family

In a typical workday, Trussart

might find himself realizing

new ideas through drawings,

working on guitars, or teaching.

“I teach everyone [who

works in the shop] how and

what to do and how things

need to be done. And that’s

a daily kind of thing,” he

explains. “I think there’s a

certain way to crown frets, a

certain way to adapt this neck

profile … we’re doing so many

different things that it’s crazy—

I probably have 500 different

parts.” Needless to say,

with that many factors, there’s

a lot to oversee while still trying

to break new ground.

All this happens at a property overlooking the world-famous hillside sign in Hollywood. It is both Trussart’s home and workshop, but it feels more like a peaceful retreat or a commune. The warehouse where more involved processes such as welding and engraving take place is about 10 minutes away, so the luthier is constantly in and out of both shops. But he still finds time to play music every day. “I try all the guitars coming out of the workshop—I play them all.”

While his operations are still small—Trussart says it’s “like a family”—demand for his time-consuming custom work has grown enough that he’s assembled a close team to whom he’s taught his intricate processes— including the rusting and aging rituals that took him years of research to perfect.

The Rust on Cream African SteelCaster Bass has an engraved African motif, maple neck, rosewood fretboard, and handwound Arcane Inc. P and J pickups.

William Raynaud, also a French native, has been working with Trussart for nine years, and in that time he's become the go-to builder in the shop. Raynaud is a musician from a musical family, but he says his background in electronics helped him excel in the world of instrument building. His specialties include painting guitars, shaping necks, rusting, distressing and coloring, and assembling the recessed body plates. Raynaud says he enjoys the painting aspect, but most of all he loves the end product. “When everything fits together and the guitar is ready and you set it up and try it out—you feel you did good.”

Whether a piece is being worked on by Raynaud, Trussart himself, or the other two team members in the shop, Christian Williams and Paul Slagle, great attention is paid to every aspect, even down to the custom aluminum knobs and Tele-style bridges— which have one side of the “ashtray” design shaved down for player comfort. “These guitars are expensive to some people,” Raynaud says, “but we spend so much time on each one of them, because they are all different [and require] many adjustments. This is handmade stuff—it requires a lot of work. It’s really intense craftsmanship.”

Trussart uses sea salt and animal skins in his complex rusting process.

Although things are busier than ever at the Trussart camp, it’s not just testament to the coolness and popularity of his work, but also to the restless creativity of the man who runs it all. Raynaud says that, in addition to overseeing day-to-day building, his other responsibility is to reel in Trussart’s ambitions. “James is the artist. He’s a really nice guy, he’s really generous, and he has so many ideas,” Raynaud says with a laugh. “But if we don’t stop him sometimes, then it’s just a big mess.”

The Guts of Glory

Although James Trussart’s head-turning metalwork and intriguing aesthetic treatments tend to get the lion’s share of attention from pretty much anyone who lays eyes on his instruments—and deservedly so—his discerning taste when it comes to hardware and electronics is cause for admiration, too. He uses CRL switches, CTS pots, and Gotoh and TonePros bridges, and when it comes to pickups, he primarily works with Arcane Inc. “As Rob [Timmons, owner/founder] is a local, he can do whatever we ask him to,” Trussart says.

Generally, the pickups us alnico 3 and 5 magnets, and output varies by guitar model.

“Wirings are pretty standard. For example, whenever we have a humbucker on a SteelCaster, we add a push-pull [knob] so you can split the coils.” The SteelDeville model has a “Jimmy Page” wiring, which gets four push-pull knobs.

Trussart also offers Graph Tech acoustic saddles on any guitar, though he uses Fishman piezo pickups with an Arcane P-90 on SteelResoGators.

An

Antique Silver Gator Steel O Matic.

The Reverend and

the Rust

Trussart discovered his now-famous

aging process—another

one of his “happy mistakes”—in

1984. He had been doing shiny,

metallic-finished guitars and

wanted to switch things up a bit.

“I was, like, ‘Hey, let’s throw a

really beat-up, junkyard-style one

in [the mix],” he says. “I did, and

[it] had a really great response.”

Back then, he got the rusty look by leaving guitars outside on the roof of his workshop in Paris, where it rains often. Trussart still leaves guitars outside to rust, but the process has evolved to be a little more methodical. He won’t divulge his secrets, but he did share that the guitar parts are submerged in bins of water and sea salt, with different ingredients added in for different effects.

“I improved the process, and now I have pretty great control over it. I have all kinds of different colors of rust, and there are a lot of little things I do so it’s not a boring rusty metal that has just been outside.”

The technique that yields distinctive patterns came about by accident, as well: Trussart left a guitar out in his yard to “age,” and some leaves fell on top of it during the rusting process. He liked the organic look of the imprinted patterns so much that he expanded his rusting process to include other patterns. For alligator and snakeskin textures, actual animal skins are used to sandwich the guitar in the soaking bin so that the patterns transfer to the body. “Probably I was the first one to do all of that,” he now says. “It’s funny to go from times when people are joking about what you do, and then to be [looked upon] as a master rust specialist.”

Trussart and his team play every guitar coming out of their operation, and they often jam with their customers. Of the

60 to 70 odd guitars hanging on his studio walls, Trussart says he has a hard time choosing just one to play.

ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons coined the term “Rust O Matic” to describe the unique look of Trussart guitars, and the name has stuck, seeing as it fits into the ’50s essence that Trussart works from. “These days, I think there’s a lot of nostalgia everywhere— I think people are kind of bored to wear the same thing,” he says. “Look what happened to cars, look what happened to all kinds of things that were fantastic when I grew up … I think people like what I’m doing because it’s kind of an echo from the past, from those years when things were genuinely built to last.”

Connecting the

Dots of Dreams

Despite Raynaud’s best efforts to

the contrary, Trussart’s creative

gears are currently in overdrive,

with new variations on his bass

models and the SteelMaster

set to be unveiled at this year’s

Winter NAMM show. He

just finished a left-handed

version of what he’s calling a

Steel TeleMaster as a surprise

71st-birthday present for R&B

singer/songwriter Barbara Lynn,

whose “Oh Baby (We’ve Got a

Good Thing Goin’)” was covered

by the Stones in 1965. “She’s

just amazing, so I made something

over the top,” Trussart says.

“It’s gold-plated with engraved

roses and her name cut in there.

It’s Cadillac green … she doesn’t

know that I’m doing that.”

The

Steel X model was designed in collaboration with Metallica’s James Hetfi eld. Pictured is one in Antique Silver Snakeskin.

Connections to artists like Lynn informs much of Trussart’s work, because players from every genre are frequently stopping by his studio to check out instruments. Most recently, the Dixie Chicks’ Natalie Maines, who’s recording a solo album with Ben Harper’s band, stopped by. “I made something really special,” Trussart confides. “She decided to try several SteelCasters with acoustic saddles that allow you to blend [transducer and magnetic pickups]. Apparently, she loved it—they recorded two songs with it the next day.”

Given Trussart’s enthusiasm and the joy he clearly feels upon hearing the sorts of feedback he’s regularly getting from big-name clients, it’s clear that we can expect much more from him in the future.

“After 30 years of guitar work, I can say that I found my own direction,” he says, “and there are more discoveries to come and fields to explore. It’s been fantastic. Every day a new idea comes, and I’m able to realize it. You dream about something and then you make the dream come true, and that’s it.”