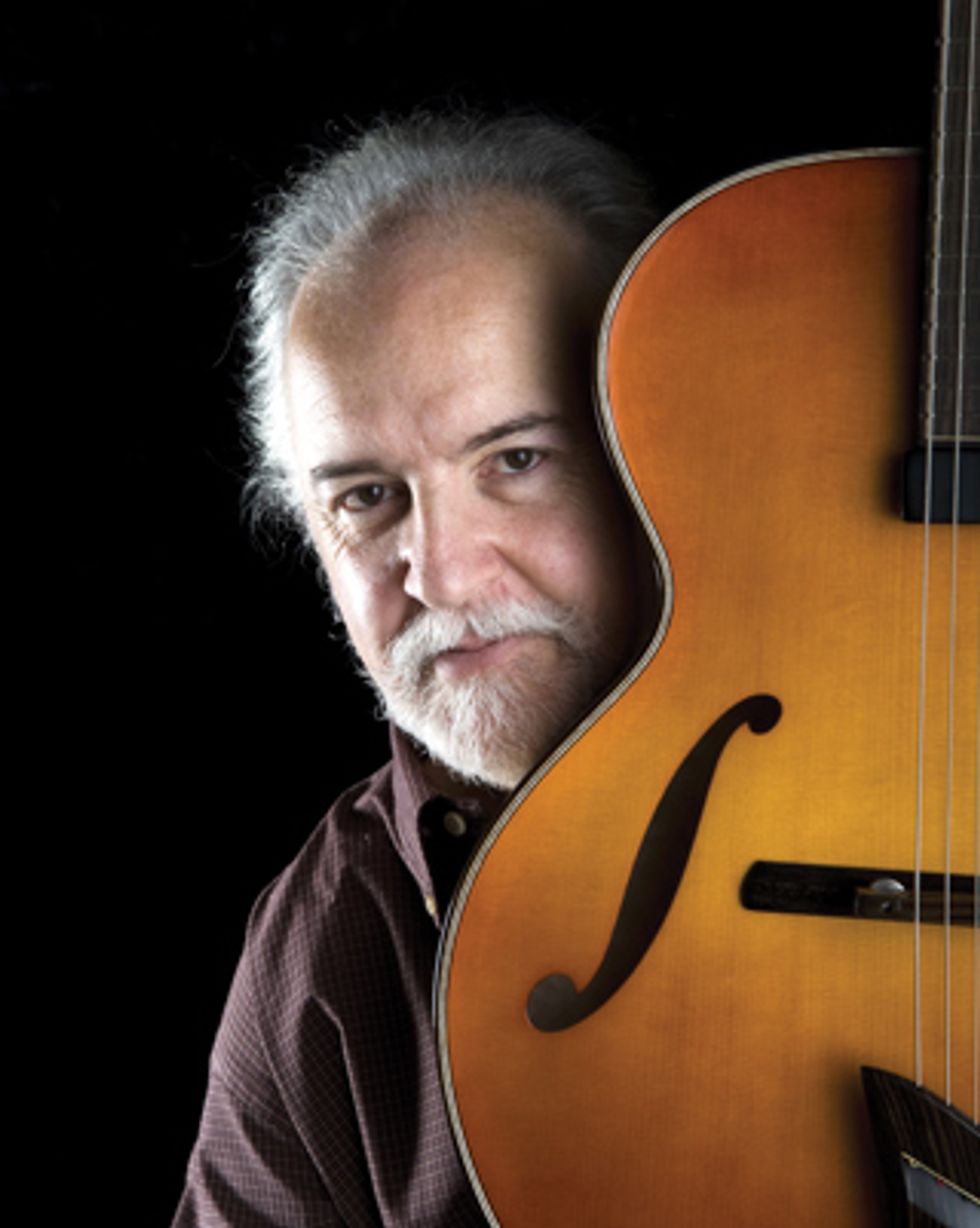

Monteleone’s Grand Artist guitars are inspired by his mandolin-making years and feature an elegant scroll on the bass-side bout. Photos by Vincent Ricardel

Taking a stellar instrument in your hands can be a bit overwhelming— especially when it’s a masterfully built piece of high-functioning art. For starters, you don’t want to ding it, drop it, scratch it, or do anything that might cause its owner pain or expense. Secondly, and possibly even more powerfully, you might not feel worthy of such an instrument.

Among the instruments likely to cause such a reaction, those built by John Monteleone up the anxiety ante considerably—like, to heart-attack level. But despite the jaw-dropping beauty of his instruments, Monteleone insists his central goal is always to make his guitars player friendly. From his early incorporation of side sound ports (which has since become much more common among high-end builders) to his use of a tailpiece that can be minutely adjusted to ease string tension, Monteleone’s archtops are a player’s dream come true in spruce and maple.

Sounding Off

Early on, Monteleone

was concerned that

the archtop had been

pigeonholed as a jazz-only

guitar. “That idea

never sat well with me,”

he says. “I knew it was

capable of much more

than that, and if I could

bring it into an arena

that was more friendly to

the broad application of

guitar, then I’d be going

in the correct direction.”

Monteleone grew up in Manhattan in a family of artists, craftsmen, and engineers, so his background suited him well in his conquest to expand and develop the archtop guitar. He spent several years working for his father on blueprints, generating different kinds of objects and things from paper to reality. It was interesting work, but Monteleone felt he was searching for something else. “I wasn’t quite sure what that would be, or if it was even possible to find a direction that I really was going to align with,” he remembers.

Monteleone makes 17" and 18" versions

of the Grand Artist scroll-body. One

client calls it “The Terminator” for its

aggressive tone, “yet it can be as mild

as you want it to be,” Monteleone says.

In a classic quest to find himself, Monteleone took off to backpack through Europe, where he hitchhiked, slept out under the stars, and dreamt about the future over a period of months. He knew he didn’t want to spend his life working in his father’s pattern shop, but still wasn’t completely sure how to craft the rest of his life. Then it hit him.

One day he was listening to the radio while working, and a show came on featuring Stan Jay and Harold “Hap” Kuffner from the Mandolin Brothers in Staten Island. “They were entertaining live, and they were fielding questions about instruments,” Monteleone says. “I think I called in to find out more about a certain mandolin—a Gibson mandolin that I had seen in a store.” Monteleone had already built some instruments as a hobby by that time, but says, “I had no idea you could turn it into a profession or a business.”

He decided to go meet Jay and Kuffner, who had just started their now-famous business of buying and selling vintage instruments and were, unbeknownst to him, looking for someone to repair them. Fortunately, Monteleone happened to bring along two flattops he’d been building and ended up getting the gig. “With a smile on my face I drove home that day with a Gibson Bella Voce banjo to re-neck as a 5-string. Also on the backseat of my Volkswagen bug was a pre-war Martin 000-45 and a D-28. What more could a starry-eyed guitar geek want to spend the rest of his days with?”

While he was working on rare instruments at the little workshop in his house over the next few years, Monteleone learned a few tricks of the trade from legendary mentors such as Jimmy D’Aquisto and Mario Maccaferri. “I was very lucky to have that experience,” Monteleone says. “Everyone has their own building styles, and I admired Jimmy’s talents. I know they’re not my own talents—and vive la difference! That’s great, everyone should have their own signature on things. Same with Maccaferri. I did some work with him purely on a friendly basis, not as a business arrangement, because I just loved the man. I knew that his approach to building was not my own, but I could appreciate it.”

Even so, Monteleone says D’Aquisto and Maccaferri influenced his luthiery in the same ways that master musicians influence aspiring musicians. “These things play into your own development of how you think about sound, about tone, about construction of the instruments, too. I wasn’t necessarily going to follow their examples exactly, but things do play into your cards at some point.”

Despite having such close working relationships with two of the 20th century’s most famous builders, Monteleone says his main design philosophies came from his hands-on experience working as a repair tech. “You’re a problem-solver when you’re doing this—you’re fixing something, you’re righting something that was wrong. Or something happened to the instrument that was not the fault of the design.” Because of that, Monteleone’s guitars are a product of his reverence for vintage instruments, as well as his desire to improve projection, tone, and playability, but not to turn a guitar into something it’s not. “In design and construction of instruments, there’s a lot to be learned from others. Some of these guys I still hold in high regard, and in some ways, you wouldn’t want to change [what they pioneered].” But in other ways, he says he found certain design aspects called out for change. “Not just to change it for the sake of changing something— that’s not a good reason.” Monteleone says such changes are warranted, however, for the betterment of functionality or user experience.

“The basic design of my instruments, the foundation, is something that is easily identifiable, and recognizable as the instrument we all know, as opposed to a spaceship, or ‘What the hell is that thing?’”

LEFT: The 25.4" Blue

Comet uses Indiana curly red

maple harvested from the

Hoosier National Forest for its

back, sides, and neck. RIGHT: Several internal

inlays of turquoise and mother

of pearl run around the interior

of the guitar’s sidewalls.

The Train: A Vehicle of Inspiration

In addition to his Four Seasons models, luthier John Monteleone has done several themed guitar projects. Here,

he shares the inspiration for his Train series, which is currently in progress.

I have been intrigued with trains since I was a child. I still have a few sets of these trains. Not unlike many other young kids, my interests were also drawn to the guitar, if not a variety of other musical instruments in my particular case. But for me, the train was about imagination. There were many other fascinations with trains, including the deco design and style elements of the great train era. It could be seen in the trains themselves, inside and out. The architecture and design of the great train stations are still with us, the ones that thankfully managed to survive.

I came to realize that many of us guitar players share this childhood activity, and there are many train enthusiasts out there who collect and have a passion for the subject. The trains that I focused on were the more famous ones that ruled the iron rails from the 1920s into the 1950s. They were known for their land speed and luxury of design. Before the jet plane replaced them, they were perhaps the most popular method of getting from city to city.

Trains were a main method of transportation for musicians, entertainers, and bands. Many songs have been composed about the subject of trains—inspiring musicians to sing songs about them and the places that either took them somewhere or took their “baby” away. The blues was a natural inspiration for a train song—Jimmie Rodgers as a case in point. I love those songs.

It seemed to me a natural connection from the guitar to a musician to a train. The next progression would be the inspiration of the train to a luthier. I could easily see how certain elements of design could be incorporated into the guitar design. The danger is, of course, to exaggerate and allow the design to get out of hand. Keeping a balance of design and allowing the guitar to be the vehicle is the challenge at hand. At all costs, it has to be a guitar that plays up to optimum standards, first and foremost. After that, we can proceed to embellish.

I leave it up to the observer to decide what he or she sees in the designs. One can, however, see on the headstock that I use the front of the train for inspiration. There is an interpretation of the headlight mounted in a bronze casting of deco design that might be seen on some of these trains.

The trains that I have

chosen as my subjects for

inspiration of guitar design

so far are the [Central

Railroad of New Jersey]

Blue Comet, the [Atchison,

Topeka and] Santa

Fe Super Chief, the [London

and North Eastern

Railway] Flying Scotsman,

the [New York Central

Railroad] 20th Century

Limited, and the [Seaboard

Air Line Railroad]

Orange Blossom Special.

There are, of course,

other models under consideration

but these train

guitars are presently in the

works and they are each

intended as one-of-a-kind

presentation pieces.

—John Monteleone

LEFT: The Blue Comet’s soundboard was carved from Adirondack red spruce, and the inlay is made of turquoise stone with mother of pearl. RIGHT: The guitars in John Monteleone’s Train series are inspired by various design appointments on famous locomotives from the golden age of passenger trains. Note the intricate details on the Blue Comet model, including the headstock’s aerodynamic shape and deco inlays.

Learning Curves

Like many luthiers,

Monteleone’s first

guitars were flattops,

mostly because of his

background of working

on them during

his teens and early 20s.

“Somehow I never

moved away from those,”

he admits. “I always

keep a flattop with me

to play myself. When I

got interested in archtop

guitars, I had that experience

behind me, knowing

what a flattop could

do, and I quickly learned

what an archtop could

do differently.”

Monteleone noticed

that flattop players had

difficulty adapting to

archtops. For starters,

archtops often seem

heavy or cumbersome

compared to standard

flattop. So Monteleone

decided to try to make

archtops more accessible—

but also more

intimate, with a more

expressive, responsive,

and immediate kind of

sensitivity.

“Archtops have a particular character of enveloping all of the notes— all the notes are put into bubbles. They’re very clear and precise. You can hear them, they’re easy to identify. Flattop guitars have that, but they’re more dragged, one over the other, and it comes at you in a different way.” Monteleone decided he wanted to bring a bit of the flattop into the archtop, response-wise. “The flattop guitar has a very adaptive kind of looseness to it. It’s easy to play in many styles, and the archtop guitar really hadn’t known too much of that in the past. I don’t think it was developed beyond a certain point.”

Monteleone realizes, of course, that art, science, and craftsmanship must work together, and that instruments must be subservient to what their owners intend to play on them. He says that the guitar-building philosophy for an instrument intended to entertain a crowd of thousands is different than the philosophy behind a guitar that will be playing to 100 people or less. And the more you reduce the size of the crowd, he says, the more the design becomes acoustic oriented.

The Teardrop guitar is Monteleone’s

homage to John D’Angelico and Jimmy

D’Aquisto (Monteleone’s close friend and

mentor), who both designed teardrop

guitars during their careers.

“The one-on-one relationship is what really interested me,” he says. “That’s what led me to build a guitar with side soundholes. The musician was going to be the first one to be satisfied in the chain. I wanted to take the ‘me guitar’ and, through experimentation, turn that into the ‘us guitar.’

“I made my first guitar when I was around 14 or 15, and I would play that guitar, fool around with it, and the sound was okay. But if I laid my head on the side of the guitar, my ear right on the side, there was a sound in there that I wanted to hear. It was beautiful, rich, syrupy, live, crisp, clean, and lush. From that day on, my curiosity led me down a path to getting that.”

Monteleone’s Teardrop guitar was part of Guitar Heroes, a 2011 exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art celebrating the work of luthiers Monteleone, John D’Angelico, and James D’Aquisto.

Function Meets

Expression

For some archtop builders,

tailpieces aren’t

necessarily high on the

list of design considerations—

at least when it

comes to innovation and

time investment. But

Monteleone’s is remarkably

functional, and it

has a huge impact on the

playability of the instrument.

The bracket that

holds the tailpiece is a

one-piece casting that

allows one to change

the rise of the tailpiece

by removing material.

A piece of ebony block

sits in a tray over which

the tailpiece anchor

strap will pass, so you

can reduce or raise it

simply by making different

pieces and changing

them out to arrive at

something that’s going

to be the best for that

set up. The tailpieces

are also horizontally

adjustable. Monteleone

likes having the option

of shortening it up

tight to the bracket, or

extending it out closer

to the bridge in order to

slightly alter the tension

of a string.

But though he dedicates a lot of attention to tailpieces, Monteleone says the bridge is what really drives everything. “The bridge mechanically transfers information from the strings out onto the soundboard. So with mandolins and archtop guitars, I focused on how to keep that energy alive, with the most efficiency possible, for the longest duration of time that I could get from it. And just for the power of tone and separation, and dynamic separation that is the complete spectrum from lowest to highest— how to smooth that all out from one end to the other was a particular objective of mine.”

His experience working with violins gave him an understanding about the connection between the bridge and an archtop’s tone bars, and how to move sound out to the soundboard. “This is one of the reasons I began to use an elliptical soundhole, and to rotate it to increase the real estate on the bass side of the guitar. And then on the treble side it was a little shorter. To have an efficient soundboard and resonator, that relationship needs to be coupled together.”

Archtops are heftier than flattops by design, but Monteleone doesn’t want his guitars to have the clunky feel that some archtops have. “There are those who are firm believers in weight reduction clear across the board when making the instrument—to make them as light as they can be—and they’re highly responsive, and that’s a fine approach. It’s not mine in particular. I don’t consider weight my enemy. I want to use it in a friendly way, put it in the right places, because I think you have things to gain in terms of tone and resonance.” After a pause, he continues. “There’s probably some scientific way to explain all that, but mine is more empirical— from that experience of having played with this and played with that, and knowing what works and what doesn’t work. And also with what the musicians would like to have. So I’ve chosen to bear that in mind. You can build an instrument totally to your own liking, but if someone else doesn’t like it … .”

Drool-Worthy

Details

One of the most interesting

of Monteleone’s

guitars is his Grand

Artist model, which

has a beautiful scroll

on the bass-side bout.

The Grand Artist began

as an extension of his

mandolin making—he’d

always wanted to make

a guitar based on mandolin

construction. It

required a neck joint

different from a normal

archtop guitar’s and,

once again, Monteleone

pulled innovation out of

deeply rooted tradition:

He’d seen an example of

a scroll-body, O guitar

from the early Gibson

years, and others from

his years repairing mandolins,

but he didn’t find

them terribly interesting.

Each of Monteleone’s Four Seasons guitars is made of wood expressive of the season it represents (left to right): All of the perimeter lines on the quilted-maple

Autumn are influenced by leaves. The natural-finish Winter uses contrasting ebony, maple, and alpine spruce. The wild tiger maple and blue hue of

Spring is to represent “the wonderful sky, sunshine, and things that come exploding out of the ground.” Summer’s scroll body and fiery colors are meant

to invoke that season’s “hot, sweaty, steamy” essence.

“They looked cool, they looked different, but they didn’t play well,” he explains. “They didn’t give the expected tone and response we were looking for.” So he steered away from that type of design and followed his intuition. He’d also built mandocellos and mandolas by this point, and with that experience, he says it wasn’t too difficult to conceptualize a guitar based on those designs. Monteleone now makes 17" and 18" versions, as well as a Teardrop model. He says the guitar’s response and tone is hard to explain. “One of my clients calls it ‘the Terminator,’” he says with a laugh. “It can be very aggressive, but yet it can be as mild as you want it to be.”

Photographer and guitarist Vincent Ricardel has worked extensively with Monteleone and co-authored Archtop Guitars with Rudy Pensa. Ricardel says there are only three guitars like the Teardrop in the world, with the first one being by John D’Angelico in 1957. “It was so unique at the time—with a lower bow that dipped and curved—and it had that ’50s sunburst color we all identify with guitars of that period,” Ricardel says. In the early ’90s, Jimmy D’Aquisto built the second known Teardrop, one with a reddish finish, in homage to D’Angelico. It was only natural that Monteleone followed suit with an homage to his mentor and friend D’Aquisto. He built his in 2008, and it features a scroll and elaborate inlay work.

Ricardel photographed all three Teardrop guitars, as well as many of Monteleone’s intimate building sessions. “If you look really closely, it says ‘In homage to John and Jimmy’ on the inside of the guitar,” says Ricardel of Monteleone’s Teardrop. “You couldn’t pay a higher compliment to somebody.”

But Monteleone is accustomed to getting compliments, too, and few could be more flattering than being invited to have his guitars displayed alongside many instruments by D’Aquisto and D’Angelico at the 2011 Guitar Heroes exhibition at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Monteleone’s markings on the insides of his instruments were made possible through his use of side soundholes. “I thought, ‘Hey, here’s a whole new canvas. Why not?’” The first guitars he decorated this way were the Four Seasons guitars, a collection he built starting in 2002. Now in a private collection, these guitars were featured in a recording by guitarist Anthony Wilson, who was commissioned by Monteleone to write a suite of music for the guitars, Seasons: A Song Cycle for Guitar Quartet (Live at the Metropolitan Museum of Art). The recording features Wilson, Steve Cardenas, Chico Pinheiro, and Julian Lage, and it was performed at the Guitar Heroes exhibit. One of the Seasons guitars, Summer, is a scrollbody model, and on the recording you can hear a range of Monteleone’s options, including f-hole and elliptical-hole guitars. Each of the Four Seasons guitars has elaborate sketch and inlay work on the interior, including genuine precious gemstones such as diamonds, rubies, and even emeralds.

Despite the unique, forward-looking aesthetics of his guitars, Monteleone is a player himself, so his designs always take into account how unique appointments will affect tone, ergonomics, and playability. “The bigger the guitar, the more shallow it’s going to be, and the smaller the guitar, the deeper it’ll be, in contrast,” he says. He even pays close attention to things as small as putting a radius on the edges of the binding so it doesn’t press uncomfortably into the player’s arm or leg.

Above all, Monteleone treasures the close relationships he forms with individual clients—he loves building each guitar to suit a unique person. “I’ve been blessed with a clientele that allows me a pretty free range of experimentation to develop ideas,” he says, “but it always comes back to hanging those ideas of design on a functioning body that will play as expected, at the least. Otherwise what good is it?”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)