A conversation with Brian Gerhard, founder and designer of Top Hat Amplifiers, is a lot like the first time you hear Bonnie Raitt, Steely Dan’s Walter Becker, or Los Lobos’ David Hidalgo and Cesar Rosas—or any of the other studio and stage elite who’ve beaten a path to the Top Hat shop door. That is, you come away from the experience humbled and reminded of what it means to be a consummate pro: incessant attention to detail, relentless devotion to quality, and an unwavering excitement for the craft. With a penchant for quintessential Vox and Marshall archetypes and the classic guitar tones of players such as Jimmy Page (with whom he shares a birthday), Gerhard has taken Top Hat from modest beginnings to stages and recording studios across the globe.

Always the perfectionist, Gerhard says he approaches his passion with a practical purpose meant to aid working players, producers, and engineers who demand top-quality tones and reliable performance. He’s emphatic in his belief that each component—from glue and capacitors to tubes, speakers, and cabinet design—has such an impact that each demands exquisite attention.

Premier Guitar recently spoke with Gerhard to talk about his early interest in hi-fi stereo equipment and how being a die-hard player informs his designs.

How did you first get into building

amplifiers?

It was all from a fairly young age. I had

piano lessons in second grade, which

taught me how to read music. Then I

had to play my sister’s clarinet before

I could start playing drums from fifth

through 10th grade, when I switched

over to the guitar. At the time, I was as

much into hi-fi gear as music, and had

started building Dynaco [tube stereo

amplifier] kits with my brother around

the sixth grade. That led to three years

of electronics in high school and more

in college.

What were you listening to when you

switched over to guitar?

Very classic-rock sorts of stuff. I’m about

to turn 49, so I grew up with a lot of

Jimmy Page sounds in my brain, as well

as a lot of the ’70s and ’80s stuff. Early

ZZ Top, early Aerosmith, early AC/DC,

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, the

Faces, and those great Rolling Stones

records—the usual guitar-rock suspects.

Was that around the same time you

started making guitar amps?

Well, I was interested in all of it. I had

a friend with a shop that did amp and

guitar repairs, so I built a lot of parts

guitars throughout the ’80s, and was

into all facets of guitar tone. For a while

I was building pedals, too, but ended up

settling on amps.

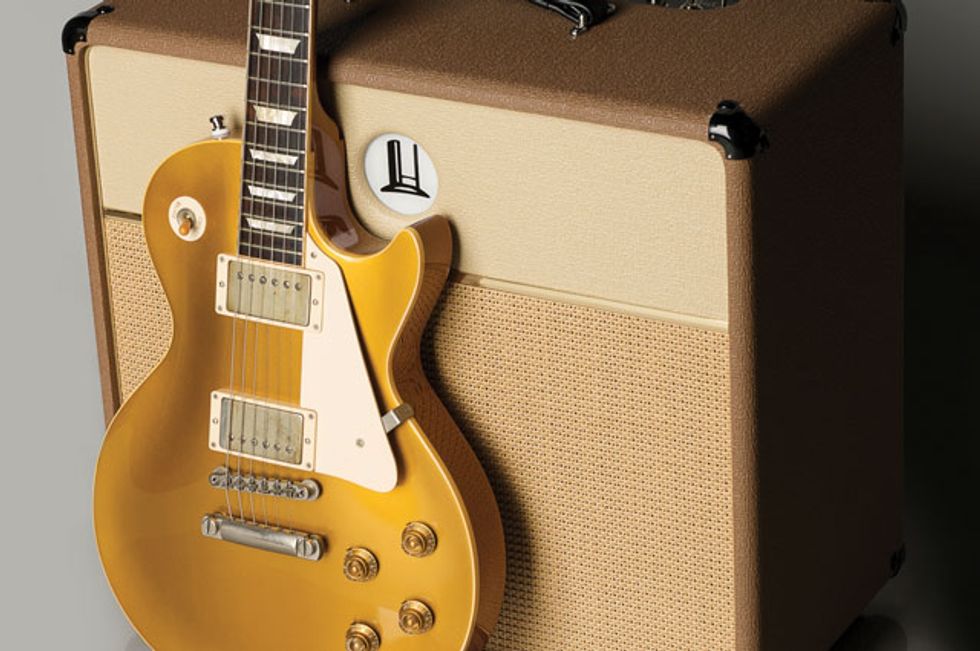

Top Hat’s Brian Gerhard

says the Super Thirty-Three

is a bestseller because of

its authentic British tones.

Photo courtesy of Fat

Sound Guitars

Top Hat’s Brian Gerhard

says the Super Thirty-Three

is a bestseller because of

its authentic British tones.

Photo courtesy of Fat

Sound Guitars

When was that and how did Top Hat

begin?

It was around ’94. I was operating some

other small businesses with a few partners

and had some extra time, so Top Hat

began as my own side business then. In

those days, the amps were all built to

order, but by ’96 we’d introduced our

standard model line with the Club Royale,

Emplexador, and King Royale.

Were there any particular clients who

influenced the development of your

line?

Not so much, since I already had my

favorite things as a player and musician.

I purposely chose to go the historic Vox

and Marshall route rather than the tweed

side of things for a couple of reasons. The

EL34 and EL84 British side of things was

more of what I grew up with, and the

whole world—including Fender—had

gotten back into tweed-inspired designs

by the mid ’90s, which meant the market

was already heavily overloaded. Also, I just

wasn’t satisfied that any of the speakers on

the market then could replicate the Jensen

alnicos of the ’50s. All things considered,

we decided to lean towards more typically

British tones, but we did add a somewhat

Fender-based reverb amp called the

Ambassador later on, but that was blackface

based.

Speaking of speakers, which ones did

you find best replicated the British

thing?

Those were—and are—available. I tend to

stay with Celestions, although for a while

when we were building little 5-watt amps

we built our own 8" speakers. With an

overseas supplier, we were able to do better

than anything else on the market, but

I keep coming back to the Celestions for

12" speakers—mostly the G12H standard

edition. And we were actually one of the

companies who got them to make the

proper 75 Hz-cone version that just came

out a few months ago. Before that, they

were making a bass-cone version, but me

and a lot of other builders were begging

them to make a proper guitar-cone version,

which they finally did.

In particular, you seem to be a big

fan of the alnico Celestion Blues you

use in the Supreme 16. Are there any

particular aspects that have elevated

that speaker in recent years, and what

makes them such a good fit for the

Supreme 16?

It’s my personal contention that when

they started the Heritage series in

England, the Blue alnicos got infinitely

better. There was a night and

day difference in the quality of tone.

Celestion doesn’t publicly acknowledge

that they changed anything, but the

glue, parts, and pieces make a huge

difference. Gluing the voice coil to

the speaker is a critical point, but the

spiders [the paper portion that connects

the voice coil to the speaker frame] as

well as doping around the top edge

are different, too. So they improved

a number of things, although mostly

right around the voice coil—and probably

the voice coil material itself.

Gerhard founded Top Hat in 1994, growing it from a side project to one of the top boutique

amp suppliers in the industry.

Gerhard founded Top Hat in 1994, growing it from a side project to one of the top boutique

amp suppliers in the industry.

So that advancement, in conjunction with the EZ81 rectifier tube—which came back into production around ’05 or so—allowed us to do the AC15 thing correctly with the Supreme 16. The EZ81 is a big deal because it’s a critical part of feeding the original amount of current to a dual-EL84 amp, which is of course what the AC15 was. That helps things to sag, squish, and breathe right. The amp itself is in an aluminum-chassis head and can be used with a 2x12 cab that we mix the alnico Blue and a G12H in. Mixing ceramic and alnico speakers helps fill out the bottom end and other parts of the spectrum that the Blue doesn’t have as much of.

A lot of players—even those who’ve

played for a considerably long time—

haven’t given much consideration to

the affect of cabinet construction,

either.

It’s not something players always think

about, but it really does have quite an

influence on the sound. Actually, part of

why we moved from California in ’05

to our current shop in North Carolina

was to be closer to our cabinet supplier,

Mojo, which we switched to at the time.

What they’re doing that the folks in

California weren’t is finger-joint corners,

which makes a stronger box and allows

you to do a single baffle in front, as

opposed to two pieces that are double

thickness. Two pieces can stifle it a bit

more, and with the single, you’re making

it more exactly how real Vox and some

of the Marshall stuff was actually made.

This did make a difference in how those

old magical amps sounded. Even the

wood and thickness of wood used for the

baffle does, too. For instance 3/4" birch

plywood makes it crazy heavy and more

dead than 5/8", which is still dead but

at least has some life left in it because it’s

not so thick. That super-dead kind of

baffle is good for a hi-fi [stereo speaker]

cabinet, but not as much for guitar.

Tweed amps were the epitome of a real

thin baffle, where it woofs and breathes

because of the softer pine wood—which

I experimented with, too, but ultimately

went in favor of birch. But everything

has a different sound.

The “Super Fat” Club Deluxe is a tweaked version of the Super Deluxe modified with a

matching pair of EL34 power tubes. Photo courtesy of Fat Sound Guitars

The “Super Fat” Club Deluxe is a tweaked version of the Super Deluxe modified with a

matching pair of EL34 power tubes. Photo courtesy of Fat Sound Guitars

Most guitarists can relate to the process

of hearing a sound in their head

and then searching for a vehicle to

bring it to fruition. How does that process

works for you when you’re designing

amps?

Well, I can tell you that sometimes what

you think would be the holy grail doesn’t

turn out to be the holy grail, and you

find out why nobody ever did it before

[laughs]—although on paper it may seem

like a great idea. Another thing I always

say is that there’s inevitably one presiding

personality at any company, and everybody

has their fortes and their weaknesses. Some

guys are much more technically based

engineers, and some are players more than

others. Different companies have different

kinds of people, and that’s going to

affect the kind of amp you build. Every

nut behind the wheel is slightly different.

I think I had good ear training in my early

days of being a hi-fi guy—I tuned my ears

that way and by playing in orchestra and

jazz band, in addition to the classic-rock

stuff. That tends to give you a more diversified

sonic portfolio than being bent too

far this way or that way.

So how do you merge the more technical

stuff with the more artsy approach

you get as a musician with good ears?

There are a lot of hats you have to wear,

and a lot of the guys are good at some of

the hats but not at the others. Some guys

make decisions based on a scope rather

than their hands and their ears. There are

all kinds of personalities with different

opinions about good distortion versus

bad distortion or how you figure that

out when you compare different types of

capacitors that are all the same value but

different mediums that sound different.

Or how different output transformers

breathe—there’s another whole world

right there, depending on whether they’re

normal, oversized, or undersized.

As far as the art and experience of knowing, amongst real vintage amps, what they were good for and what their shortcomings were, it pays to know the difference between which ones were good and which ones were bad. Take Marshalls, for example: Some Marshall-copy companies do umpteen different styles. But, to me, you can tell whether they know what the good ones were in their choices—do they make a ’67 100-watt, or a ’68, or a ’69? I know which ones are the standouts as the holy grails. All these choices inform the art. And when you’re trying to accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative, being a player and being able to feel the response in your hands rather than just what an engineer might see on the scope lends itself to different choices than a purely technical builder may make.

Top Hat’s “Super Fat” Club

Deluxe. Photo courtesy

of Fat Sound Guitars

Top Hat’s “Super Fat” Club

Deluxe. Photo courtesy

of Fat Sound Guitars

It all does make a difference, and you really have to do the R&D and try everything under the sun to figure out what’s right for yourself—[for example] whether you like normal primary impedance. Do you like it lower? Do you like it higher? People can tell you what that does, but until you put a lower, medium, and higher one in the same amp and see what it does, you never really know for yourself. You really don’t know until you try all the different kinds of caps, which make a very big difference, too.

Sort of like exploring everything you

know on the guitar in order to formulate

your own style.

Exactly. You start with that and proceed

accordingly, which leads to another

thing: In a way, the circuit has so little to

do with [the final tone] that you could

give 10 builders the exact same schematic,

but if they just choose their own

transformers, capacitors, and change the

filtering up or down, you’ll end up with

10 different-sounding amps. The classic

circuits are a basic guideline, but I would

say our overriding philosophy from the

beginning was to try to have amps that do

what the greatest top five ever did—with

much more versatility.

Which is, of course, hard to get with

some of the great old ones, love them as

we do. They’re just not all that usable in

a wide variety of situations.

Absolutely. Like on a top-boosted AC30,

you get volume, treble, and bass. With our

King Royale, we add a midrange knob, a

fat-off-bright switch that varies the gain in

the preamp section, and a master volume.

If you dime the master, put the mid at

10 o’clock—which is where Vox fixed the

midrange—and put it in the fat mode,

your circuit is identical to a standard topboost

AC30. But you also have the option

to change your midrange, engage the fatoff-

bright switch, or adjust the distortion

with the master so that it works at a much

lower volume than you’d be stuck with on

the vintage ones.

That’s my philosophy—even on the Emplexador, where you’ve got the bright boost, the fat boost, and the master volume added to what would otherwise be a dead-bone Marshall plexi circuit: You can always get the original Marshall sound, but you can get a lot of other things, as well. Great as the old ones were, they’re impractical most of the time. Nobody can play that loud, even with a 45- of 50-watt amp with no master volume. Once you put it up to the sweet spot, you’re loud as hell, the singer’s having a hard time being heard, and the sound guy’s upset [laughs].

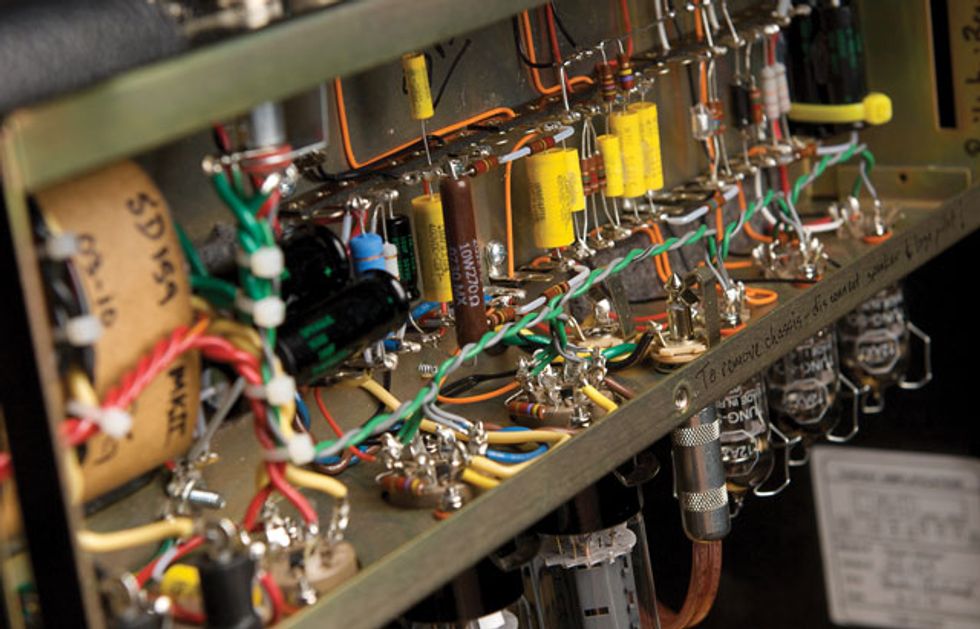

An inside look at Top Hat’s “Super Fat” Club Deluxe shows the military-grade, terminal-strip

construction and custom-wound Heyboer transformers.

An inside look at Top Hat’s “Super Fat” Club Deluxe shows the military-grade, terminal-strip

construction and custom-wound Heyboer transformers.

So you’re trying to appeal to vintage

purists while offering more options.

That’s what I gave a lot of consideration

to—why anybody would possibly sell my

amp. I tried to address those problems so

that they would keep it for life and never

want to sell it. With the exact copies that

don’t improve upon the vintage ones,

yes, you’ve made an ideologically pure

model—but it’s impractical and unusable

so much of the time. Of course, there are

a few people man enough to handle those,

as in the case of a real tweed Deluxe in the

studio. But it’s still expensive to build with

very limited capability, so what happens is,

as the amplifiers pile up in your collection,

the one that’s not getting used so much

ends up getting sold for something else. I

tried to learn from all that very early on,

and folks tend to sell mine a lot less than

they do others. If I had to compete with

myself on the secondary market, or if they

weren’t bulletproof so that I had to be fixing

old amps all the time, I’d be pulling

my hair out. That is why I build them so

that they don’t mess up and are practical—

to keep people happy for life rather than

to be the flavor of the month.

You’ve got a pretty impressive list of

stage and studio heavyweights using

your amps. Is there a particular artist or

story that makes you smile most?

I’ve never lived on hype. Our reputation

has always lived off performance and

the number of studios—somewhat in

Nashville, but certainly in L.A.—with

Top Hat amplifiers in them. It’s been

quite affirming, so we’re proud of that. I

get confirmation all the time from guys

at the Record Plant, Sunset Sound, and

the big working studios where they’re

still making records. At that level, the

proof has to be in the performance with

Mr. Microphone on them, making actual

records and letting guys with great

hands express themselves. That’s what

engineers tend to love—that [amps] are

easy to work with and user-friendly so

that there’s no work involved. Instead

of struggling to find the sweet spot at

the right nano-inch around the voice

coil, you can just put a good mic back

a foot, turn it in towards the speaker,

and you’re done.

Builder Brian Gerhard often uses Celestion speakers, but opted for the Scumback H75-LHDC

for the Club Americana 1x12 amp pictured here. Photo courtesy of Fat Sound Guitars

Builder Brian Gerhard often uses Celestion speakers, but opted for the Scumback H75-LHDC

for the Club Americana 1x12 amp pictured here. Photo courtesy of Fat Sound Guitars

There I was at Sunset Sound with John Shanks [producer/guitarist who’s worked with Keith Urban, Bon Jovi, and Van Halen, among others], when the guy from the other room was having trouble getting a good sound. So John handed him his 1x12 Club Royale and the guy came back so happy with how easy it was to dial up a tone and hit the red button. Experiences like that make me grateful for getting to do what I love, day in and day out.