If you’re one of the tens of thousands of guitarists who’ve checked out YouTube gear-demo guy Pete Thorn’s terrific video of the XTS Atomic Overdrive pedal, you may be wondering, “Who are these XTS guys?” XTS—short for XAct Tone Solutions—is Greg Walton’s pedal and effect systems company, and the Atomic Overdrive is just one of the stompboxes manufactured under the XTS brand. But XAct Tone Solutions is more than a stompbox company. The pedals evolved as part of the outfit’s larger mission: creating tone solutions for guitarists.

The company’s main office is in Nashville, but founder Walton lives in Houston, where he also works as an environmental consultant. “I was doing pedalboards for players in Houston and Austin, just because I liked to do it,” he recalls. “Back in the ’80s, I built racks for myself. From time to time I would go to L.A. and hang out with Dave Friedman at Rack Systems, trading him labor for knowledge. XAct Tone Solutions started in 2001 with me modifying pedals that weren’t reliable, or just didn’t sound great. I started like Robert Keeley, modifying Tube Screamers and DS-1s to make them sound the best they could.”

By 2006, Walton had decided it was easier to build a pedal from the ground up than mod an existing one. His first model, the Precision Overdrive, was based on an Ibanez Tube Screamer. Walton’s version has more gain on tap but still cleans up enough to serve as a boost. “It feels more like an amp than a pedal,” he says. “That’s the thing we shoot for in a gain pedal: Not only do you hear an amp-like sound, but you experience an amp-like feel under your fingers.”

By 2009, Walton’s pedal-building work had grown to a point where he started subbing out work to Nashville’s Kingdom Amplification, where future partner Barry O’Neal worked. Walton would design the pedals, while Kingdom would do the printed circuit boards and some engineering.

The Tejas Overdriver has all the capabilities of its mother—the Tejas Boost—but adds overdrive and fuzz to the mix. These units are currently being built as one-off prototypes as XTS continues to refine their design.

Growing Pains

Walton and O’Neal opened the Nashville company in 2011, focusing on both pedal designs and system integration via pedalboards and rack systems. “I could see there was a need for someone who could do pedalboards and rack systems in Nashville, especially someone with Barry’s knowledge of electronics,” says Walton. “He has a masters in electronic engineering, so there isn’t much we can’t design.”

It may not have been the best time to start a business—Nashville was still reeling from the 2010 flood, and the economy was in recession—yet Walton was confident. “Things have taken on some momentum,” he says. “We have enough boards out there that we are starting to get some good referrals.” Coming from guitarists such as Keith Urban, Tom Petty, Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds, Scott Henderson, Oz Noy, plus many high-profile touring sidemen, those referrals carry weight.

Walton currently commutes from Houston, spending a week or so at a time in Nashville. But he believes the business will pick up enough by next year to allow him to work full-time in Music City.

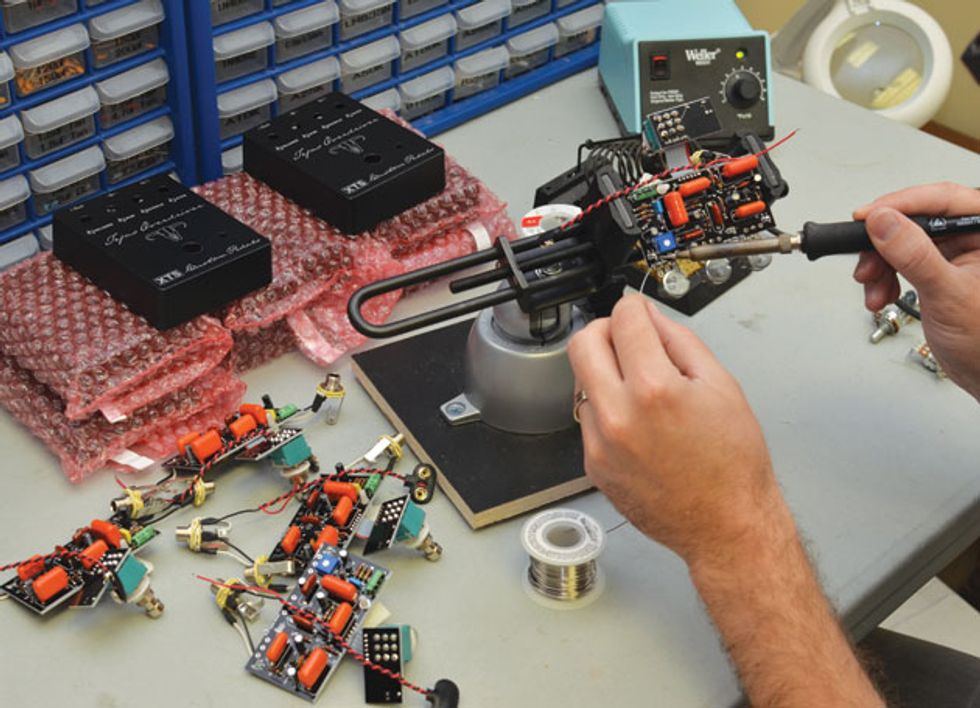

When XTS receives pedal casings from its powder-coating and silk-screening vendor, each unit is inspected by hand for errors in paint, printing, or machining. They’re then prepped for the next phase of assembly, a process that includes removing paint flashing from the machined holes and installing enclosure-mounted components. When this process is complete, these enclosures will receive serial numbers and enter the build stream.

Refining the Classics

Many of Walton’s pedal designs are derived from vintage models. “We try to improve pedals that guys like, but which have characteristics they don’t like,” he explains. “Our Imperial Pedal is sort of based on the Nobels overdrive, but we engineered out the things that guys didn’t like. Most players keep the spectrum [tone] control nailed at 1 o’clock, so we took ‘1 o’clock’ and spread it out to afford more control. We also made it bulletproof, using the best resistors and caps, while keeping the overall vibe players like.”

Other examples of XTS attempts to better other companies’ designs include the Tejas Boost, which is based on the old Colorsound Boost. “The original Colorsound had volume as a trim pot on the circuit board, and the gain control was on the outside of the pedal. We moved the volume to the outside as well,” says Walton, adding, “Our Iridium Fuzz is not your classic fuzz—it uses an IC chip for the fuzz sound instead of discrete transistors. That makes it stable and able to stack well with overdrives.” Meanwhile, the XTS Pegasus Boost is a single-pot boost with up to 20 dB of extra gain. “It’s similar to the old Alembic Stratoblaster in a pedal form,” Walton explains. “[Little Feat’s] Lowell George used the Stratoblaster, and I believe when you plug into the FET section of a Dumble overdrive, it’s the Alembic circuit.”

All these pedals and more are assembled and tested at XTS’s Nashville shop, with some sub-assembly handled offsite. Circuit boards, jacks, and footswitches are separated from the main board to reduce stress.

but which have characteristics they don’t like.” —Greg Walton

XAct Tone’s commitment to quality control reveals an interesting fact about pedals: It’s not just (in)famous vintage fuzz effects that can vary greatly from unit to unit. “You can get a hundred pedals of the same type from the same manufacturer, but because of parts drifting you might get a hundred variations in the sound,” says Walton. “We rectify that by testing each pedal to make sure it doesn’t sound too bright or too tubby. We change the values of a resistor or a cap if we need to.”

Here O’Neal chimes in. “Some of it is design, as well. For example, we designed the Atomic Overdrive so it could be more consistent and less sensitive to component tolerances.”

Walton and O’Neal test every unit for sound and feel. “We run them through Naylor and Fender amps,” says Walton. “If one’s too bright and we can’t fix it, we scrap the board and move on. One of the core qualities of this company is that we won’t sell anything we wouldn’t go out and play ourselves.”

Design This System, Smart Guy!

Having seen some XTS systems in action, I thought it would be fun to put their team to the test. I brought in some offbeat effects and challenged them to create a pedalboard that would help me use them all live. My test pedals:

- WMD Geiger Counter (waveshaping, bit crushing distortion)

- Zoom MS-100BT MultiStomp (slicers, choppy trigger delay, etc.)

- Electro-Harmonix Superego Synth Engine (sampling)

- Alesis Bitrman (ring modulation and frequency shifting)

- Source Audio Hot Hand Wah Filter

- Source Audio Soundblox 2 Dimension Reverb

- DigiTech JamMan stereo looper

To make it even more interesting, I planned to use a Pigtronix Keymaster loop box to run the right channel of the stereo Zoom and Alesis units in the Superego effects loop, with their left channels running directly through the chain.

“This will be different,” admitted XTS design-meister Barry O’Neal.

He sent me home to lay the pedals out and plug them in to make sure the concept worked the way I envisioned. When I brought them back, he said, “The next step is to arrange it so it makes functional and aesthetic sense. Which things are you going to need to stomp on the most?” The most frequently used pedal usually go in the front row, he explained, with the most important nearest your right foot (assuming you’re right-footed).

The Superego needed to be in front so I could grab short samples, and the JamMan had to be handy for creating loops. The Source Audio and Alesis pedals were raised on a platform with the power supplies beneath them. O’Neal built a small riser for the Zoom, and the WMD ended up on top of an interface/buffer. O’Neal built the interface so I could insert an additional pedal as needed, after the WMD but before the other effects.

Powering these oddball effects proved to be the main design challenge. But two Voodoo Lab power supplies—a Mondo and a Pedal Power AC—met the varied power requirements. O’Neal built a custom cable to power one supply off the other. “Power is the least romantic part of building the board,” he says. “Many DIYers lay out their pedals and then say, ‘Uh-oh—where is the power going to go?’ Also, wall-warts and digital devices can throw sonic trash into the mix. Gain pedals can amp that up, or mess up the grounding. Voodoo Lab power supplies isolate the power, though, so we didn’t have that problem here.”

When I picked up the board, it fired up perfectly the first time, was dead quiet, and worked exactly the way I dreamt it would. Every pedal was accessible, and the wiring was elegantly arranged. Further, working with XAct Tone was a joy. O’Neal listened patiently as I thought aloud, and he ran through options as fast as I could come up with ideas, however crazy they might be. Experience, attention to detail, and an ability to intuit what the player wants and needs—which aren’t always the same thing—allow O’Neal and Walton to say, “No problem!” even when confronted with a board as unusual as mine. That’s what keeps top players coming to XTS for their system design needs.—Michael Ross

Before going into final quality-control and playing tests, four Atomic Overdrives— XAct Tone’s most popular model— go through final assembly, where they receive batteries, lids, knobs, and their second-to-last visual inspection.

Nashville is an ideal place to have players test pedals and offer feedback. “I need to hear great players play,” says O’Neal. “If I’m chunking along on my own, I won’t learn as much. When we first started working on the Atomic, Greg would talk about ‘feel,’ and my eyes would roll internally. My engineer brain would think, ‘What does that even mean?’ But Greg could articulate what he meant—he’d say, ‘When I do this, it should sound like this,’ which is much more helpful. That was a huge revelation to me. I was focused on the sound, but for Greg, it also had to have the right tactile response.”

While trying to improve on a classic pedal, Walton might reject dozens of parts in search of the sound players love in the most popular version of the original. “Barry asks how I can hear that stuff,” Walton says. “After years of me saying, ‘It needs to be chewier,’ or ‘crunchier’—all the words guitar players use—Barry has learned the language.”

O’Neal has also learned he has to hear what the client hears. “Guthrie Trapp brought in a delay pedal,” he recalls. “He thought the repeats sounded like garbage. At first I couldn’t hear it, but as he kept playing, I eventually could. Now I can never listen to that pedal again. It’s like one of those optical-illusion posters—once you see it, you can’t not see it.”

XTS is happy to work with both pros and bedroom players, but recognizes the two groups may have different concerns. “The people who are not getting paid to play are more concerned with finesse and minutiae,” O’Neal explains. “They are a little more obsessive—which is fine, because we are obsessive, too. But pro players are more matter-of-fact. They realize that a lot of detail is lost onstage with a band. If a guy is on in-ear monitors, he’s going through so many systems before the sound gets to him that there’s no point worrying whether the resistors are carbon comp or metal film. For example, we recently did a rig for a big band. We’re usually OCD, but for them it was, ‘Just get it to work.’ They had neither the time nor the inclination to sink a bunch of money into a rig that was going to be redone in six months anyway.”

“It’s great to stand in front of a speaker cabinet and a ’68 plexi Marshall head, playing through your favorite pedals,” says Walton. “But for professionals, it doesn’t mean anything. They know it’s going to be miked and that they’ll hear it through monitors or in-ears. But for guys at home, hearing that stuff is awe inspiring.”

Still, both amateurs and pros are affected by what they hear. “It’s a closed loop,” notes O’Neal. “If a player hears a sound that doesn’t gratify, he doesn’t play as well. And when he isn’t playing well, then it genuinely doesn’t sound good: It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Writer Michael Ross’ pedalboard after getting the XTS treatment. XAct Tone’s Barry O’Neal built the board, which includes a small riser to make the Zoom MultiStomp (center) more accessible. Ross’ WMD Geiger Counter was placed atop an XTS patch bay, which also acts as a signal buffer and includes a loop that allows the guitarist to insert another stompbox between the WMD and the rest of the effects.

Whisper Campaigning

In addition to designing effects systems and pedals, XAct Tone Solutions does repairs and modifications. Walton says their approach here mirrors their design philosophy: “Guys come in with a pedal and say, ‘It does this, which is great, but I have a problem with this other thing.’ We try to solve as many problems as we can.”

Most repairs and mods are for players with whom XAct Tone has a relationship. “We don’t really advertise that we do repairs,” says O’Neal. “It just worked out as a value-added service for our clientele—like the guy who was in here earlier today: We built a switcher for his old Gibson Scout amps, and now he brings us all his stuff.”

XAct Tone Solutions remains largely a word-of-mouth outfit, but that word is spreading. “We haven’t done a lot of pedal marketing, because we aren’t yet geared-up to build thousands of a particular product. We hope to resolve that in the future. Ultimately, we want to make musical instruments, so if our pedals inspire someone to play something on a track or write a song, that’s the most gratifying feedback we can get.”