|

|

Preparing to Apply

Preparing to ApplyYou might begin by asking, “Why a patent?” The basic concept of the patent is to protect your invention from being used by others without your permission. There may be many reasons to try to obtain a patent, but often it revolves around economic protection of your invention. You can usually do three things to generate a financial reward for your creation:

- You can sell parts or the whole patent outright, which is called “assignment.” This may seem like good and quick upfront money, but the risk is that you may be selling your invention too soon, before its value matures through market awareness and demand.

- You can license the use of your patent to others in exchange for royalties. Royalties can be anything that you stipulate and agree on with your licensee; money, land or even livestock! A royalty is usually paid to you as a percentage of each item produced or sold using your invention. This is potentially a good stream of revenue, but it may take years for that stream to turn into a river.

- You can do it yourself, meaning producing and bringing your invention to market on your own. Often, to prove the usefulness of your gadget, the market demand has to be proven by you. Who better to prove this than the inventor? You hold the total destiny of your invention in your own hands, giving yourself overall freedom – the downside is that you’ll bear the total expense and risk of the entire venture.

The only other reason for obtaining a patent may be completely self-motivated – just to say, “I have a patent … I’m an inventor!” No matter what the motivation, these are all valid reasons for taking the time to apply.

For you, a patent provides the exclusive right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling your invention for a limited period of time. Utility patents protect your invention for 20 years starting from the original filing date. This boils down to giving you the exclusive opportunity to help your invention prosper, and to realize its full potential as a novel item. The patent system also spurs new creativity for future technology by offering protection to the inventor.

But before you rush to apply for a patent, you should first assess the potential of your own invention. Ask yourself, along with some trusted friends (yes, everybody signs a non-disclosure … even Mom) whether or not this is a cool and catchy idea, or, at the end of the day, if it is simply quirky. As tough as it may be, be honest with yourself and your invention.

If everybody flips over it and agrees that it may be an original idea, then you will want to take the next step and retain the services of a professional patent attorney. Stay away from the “all-in-one” patent/ marketing firms that promise to take your idea into the stratosphere and make you an instant millionaire. Many times they have ulterior motives which don’t involve you. During your hunt for the right patent attorney, do not be afraid to ask a plethora of questions, and be firm on seeing references of other patents they’ve been involved with.

The Patent Search

The Patent SearchThe next step is performing a “patent search” on your idea, which more than likely would be sourced out to a professional patent searching firm for a minimal fee. The search involves looking for pre-existing patents on file at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) which may be in conflict with your invention. A good search might discover that your idea has already patented by another inventor, or it could find material within a similar patent which may be close to your design in some way. Fundamentally this exercise is to unearth as much preexisting patent material that relates to your invention.

However, you don’t necessarily have to outsource the search stage of the patent process; you can do a lot of patent searching yourself, if you have the drive and patience to do so. The USPTO provides a free online search service which is open to the world. Simply go to uspto.gov/patft/. Here you can do a quick or detailed search for any issued or publicly posted pending patents on your own.

If you and your patent attorney agree that the search was favorable on your part, meaning that no matching or similar patents have appeared, then the next step is to create a “disclosure” document. This can be a fairly simple text document with some drawings or sketches that best describe your idea, how it works and why it’s original. This is submitted to the USPTO, and simply kept on file. The disclosure is not examined in any way … just filed. This provides proof of your invention, tied to a specific date. If someone else surfaces claiming to be the inventor of your idea, this document will allow you to compare dates and see who was first.

The Patent Application

After the disclosure is filed then you can proceed with creating the actual patent application document. This is most often segmented into six parts: the abstract, background of the invention, brief description of the invention, drawing summary, drawing details, and patent claims.

I would highly recommend getting yourself familiar with patent lingo, mainly by studying a few semi-related patents found online. You’ll start to get a sense of how to structure your work for your own application. To the beginner or outsider, this can be a tedious experience, but it’s a necessary step in getting the most out of your case. Remember, the application process tries to prove that your invention is worthy of the prestigious USPTO seal, and it may be examined alongside hundreds of similar patents, by several patent examiners. Your case must be airtight.

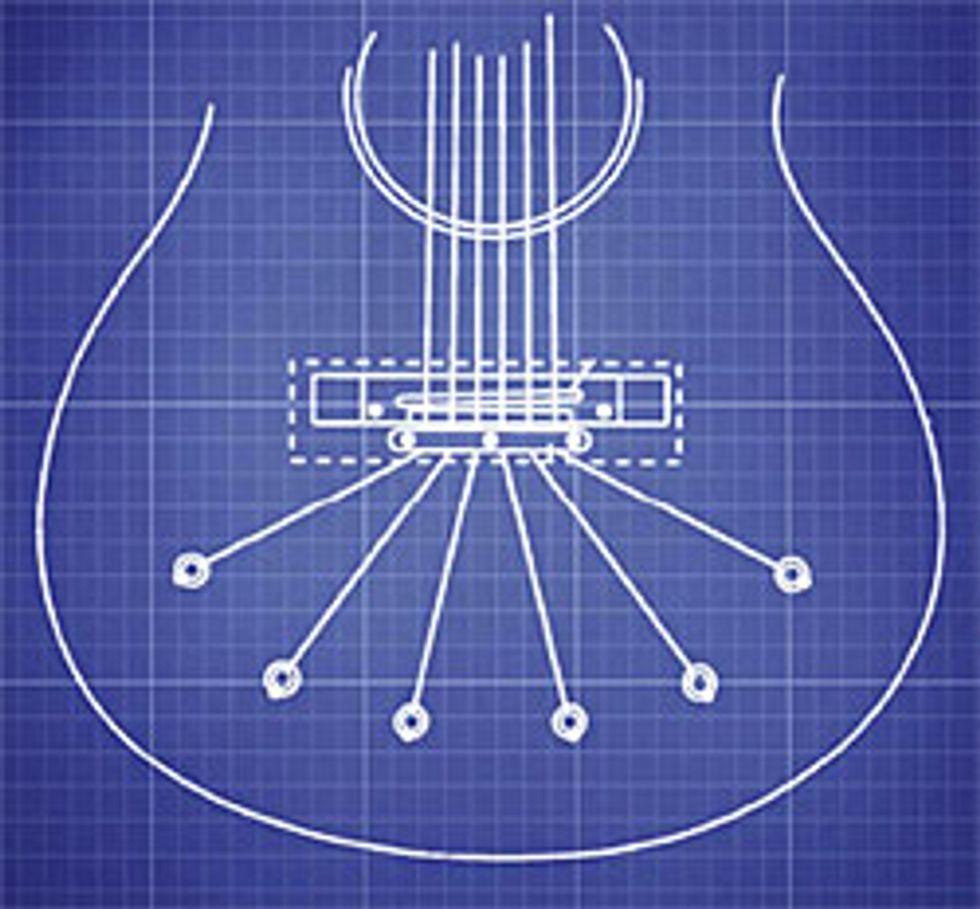

Nobody knows your invention as well as you do, so it’s your job to convey the nuances of your design and function to your patent attorney in the clearest way possible. Try writing the entire patent yourself in everyday terms, providing sketches of your item with different object views. Don’t worry about grammar or the patent structures; just get the design and concept facts dead on. Your patent attorney will take what you have laid out, dress it up and prepare it in the proper patent jargon – drawings and all.

Nobody knows your invention as well as you do, so it’s your job to convey the nuances of your design and function to your patent attorney in the clearest way possible. Try writing the entire patent yourself in everyday terms, providing sketches of your item with different object views. Don’t worry about grammar or the patent structures; just get the design and concept facts dead on. Your patent attorney will take what you have laid out, dress it up and prepare it in the proper patent jargon – drawings and all. A word to the wise; don’t take anything as gospel, just because your attorney “told you so.” Ultimately, it is your responsibility that the facts within the application are 100% accurate, and that you are comfortable with all the application’s parts. If you are not happy with certain details of the application, get it fixed. It is your dollar and your name on the patent. Remember, the beauty of a first-rate patent application lies within the accuracy of the details.

The Examination Process

After your attorney files your application get ready to wait. The first examination process can take as long as 12-24 months. There are no guarantees regarding the first examination time line – you may get lucky and get a faster response, but remember, this is a tedious process. No matter how long it takes to get your first examination, you should receive written confirmation of receipt of your application from the USPTO within a few weeks after filing.

Eventually you will receive notice from your attorney that your invention has been evaluated by an assigned patent examiner from the USPTO. When the written examination arrives, be expected to answer many questions, keeping in mind that your patent claims may be severely challenged – if not flat out denied by the examiner. Get ready to argue every point of dispute in detail, proving that your invention is original. Your patent attorney and you have the right to speak with the examiner directly over the phone, or you can request a direct, faceto- face interview with the examiner at the USPTO, located in Alexandria, Virginia. Here you have the opportunity to present a working example of your invention to the examiner if he or she is “stuck” on a specific point of your application.

Eventually you will receive notice from your attorney that your invention has been evaluated by an assigned patent examiner from the USPTO. When the written examination arrives, be expected to answer many questions, keeping in mind that your patent claims may be severely challenged – if not flat out denied by the examiner. Get ready to argue every point of dispute in detail, proving that your invention is original. Your patent attorney and you have the right to speak with the examiner directly over the phone, or you can request a direct, faceto- face interview with the examiner at the USPTO, located in Alexandria, Virginia. Here you have the opportunity to present a working example of your invention to the examiner if he or she is “stuck” on a specific point of your application. Whether you request an interview or not, the examination process can ping-pong back and forth many times between your patent attorney and the USPTO examiner, potentially making it a costly process. Be prepared for this, because it’s difficult to determine how long the application examination process can take, and every tick on the clock is another dollar. Don’t underestimate how much a patent can cost. Very rough estimates can range from $10,000 to $30,000 or more, depending on the complexity of your invention. This does not include overseas coverage, which in itself can add up to a fortune just in translation fees alone.

If all goes well, you’ll receive notification that your patent application has been accepted by the USPTO. You should feel good (and slightly relieved), as this is a major accomplishment of which you should be proud of, joining an elite class of inventors. You have struggled through the trials and tribulations of legally protecting your ideas through the U.S. patent process, and you’ve worked hard for your patent. Now it’s time to unleash the hounds and let your patent work hard for you.

| Interested in patenting a new guitar design or part you’ve invented? Here’s a few sites that can help you along the way: The USPTO For over 200 years, the United States Patent and Trademark Office has been granting inventors peace of mind and keeping the process of invention rolling. If you are serious about patenting one of your inventions, spend a few hours (at least) reading through all the information here: uspto.gov Google Patent Search For those who like the simplicity of Google, you can now search the entire U.S. patent database at your leisure. With approximately seven million searchable U.S. patents, you should be able to find what you’re looking for. You can even download a PDF of any patent you’ve located. google.com/patents Invent Now Invent Now is a non-profit organization encouraging and helping inventors of all stripes. You can find a wealth of information to help prep you for your patent application, as well as a variety of inventor resources, such as workshops and continuing education. invent.org |