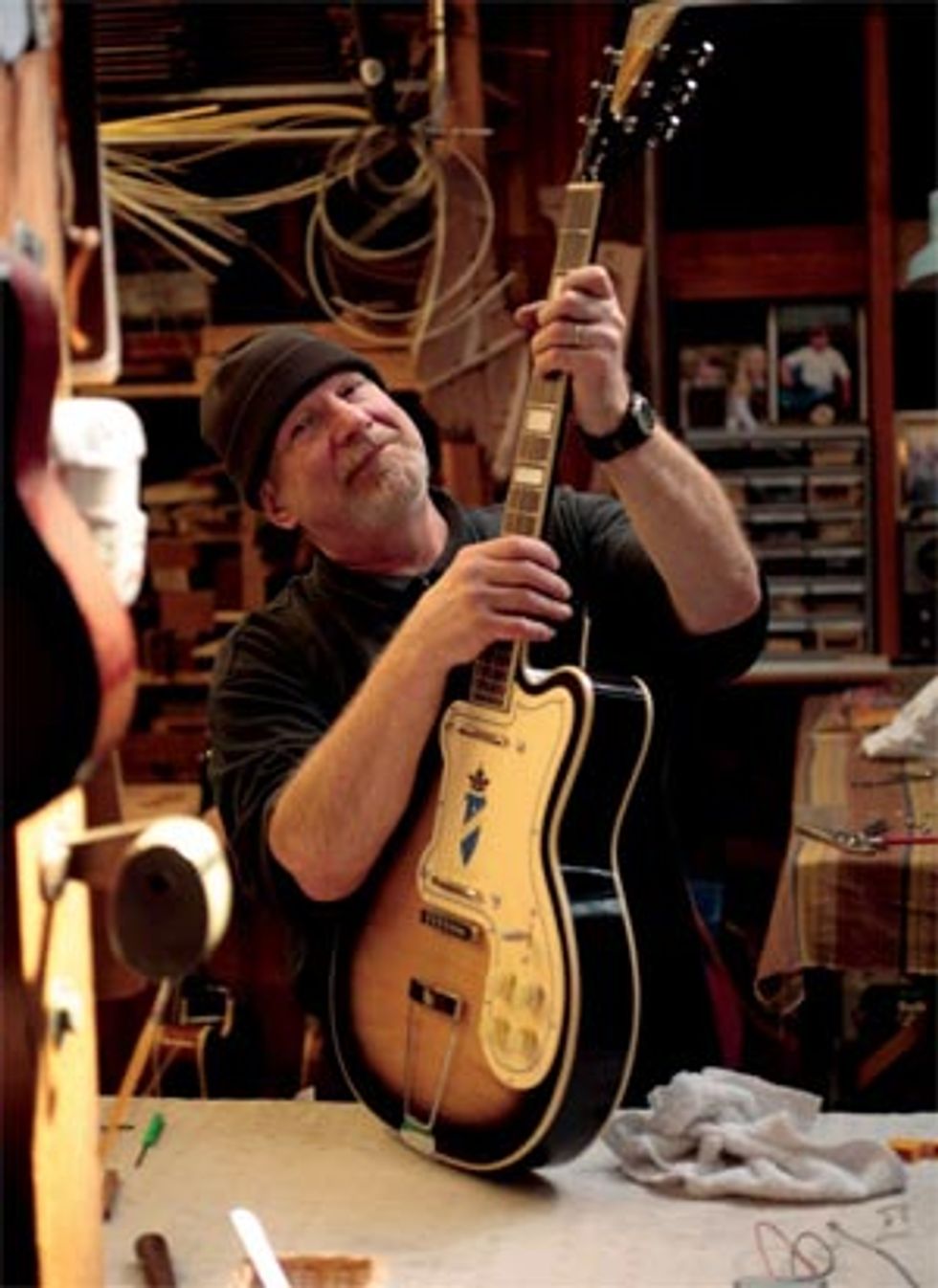

Some years ago, Roger Fritz—a bassist turned builder who builds custom instruments like the Rat Bastard, Super Deluxe, and the Roy Buchanan Bluesmaster at his 2000-square-foot shop in Mendocino, CA— was at a recording session with a famous producer who piqued his interest in Kay guitars and basses. Before long, Fritz found himself becoming a key player in bringing the funky-chic brand back from the dead.

If Kay is a new name to you, one thing you should know is that, at one point in the 1950s, it was among the biggest manufacturers of guitars in the world, building instruments under a variety of names and at a wide range of price points. In fact, Kay was actually the first to mass produce an electric guitar—a flattop acoustic instrument with a transducer—long before Fender and Gibson became household names. Over the years, discerning players and collectors have discovered some of the company’s more upscale models. For example, the original Kay Thin Twin was a favorite of blues great Jimmy Reed, and it might just be the coolest-looking guitar ever made, with its flamed-maple top, checkerboard binding, and tiger-striped pickguard. (It sounds pretty darn good too—just ask T-Bone Burnett.) Further, the original Jazz II model was favored by a very young Eric Clapton, and it can still be seen strutting its Deco stuff on stage with Sarah McLachlan.

It’s a well-known fact that vintage Gibsons and Fenders are priced well into the stratosphere these days, and the aforementioned original Kay models, as well as the company’s Barney Kessel series, are likewise becoming increasingly valuable. That’s why it’s so cool that Kay is back in business and ready to put some of that mojo in your hands for more down-to-earth prices. Let’s let Fritz tell us how it all came about.

What attracted you to Kay guitars?

I was working with singer Shelby Lynn, who was being produced by Bill Bottrell at the time. Bottrell had an affinity for the Kay 162 hollowbody electric bass—he said it was his secret weapon. When he was working with Sheryl Crow, they would try other basses on a track but would always end up using that one. I had built Bill a couple of guitars, so one day he said, “If you did a replica of this Kay bass, I know it would be a hit.” I said, “You’re probably right,” and I built one. People started wanting them, so I built a couple of dozen, and then a few Thin Twin guitars.

How did you become involved with the reissues?

My friend Dan Erlewine forwarded me a message from Tony Blair, who had bought the Kay trade name in the ‘70s. For 30 years, Tony ran it as an importer of low-end musical merchandise, then he decided that he wanted the company to get back into making guitars—for that to be his legacy. His email said he was looking for someone to help him recreate some of the popular Kay models from Kay’s heyday in the late ’50s. I figured that if he got someone else, my making Kay knockoffs might become a problem, so I responded to him. If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em, right?

I ended up doing all the designs for this new line. We are having them made in China, but I suggested that the people who were real collectors should be offered a USA-made version. He agreed, so I formed the Kay Custom Shop. I make the American handmade stuff in my Mendocino shop.

Fritz with a Kay K162 Pro Bass |

What would you say are some of the most unique features of these guitars and basses?

The Kay bass was the very first hollowbody production bass, and it has a certain sonic capability that, to this day, no other bass can really get. The 162 has a subsonic sound that worked really well at the low volumes of the blues bands back then. The body has two fairly large braces running down the middle, from the neck block to the tail block. They keep the body from caving in and add sustain. It has a curly maple plywood top and back, and on the originals the arched back was pressed into the body. This method of construction is what kept it from feeding back. The new Thin Twin guitar is basically the same instrument—same body, same pickups—just made into a guitar.

What else can you tell us about the pickups?

The pickups Kay manufactured were fairly microphonic, so they would pick up sound through the entire body. Later on, Kay developed a copy of a P-90 pickup with Barney Kessel. It was a bit hotter than the P-90 that Gibson was making, and people called it the “Kleenex box” because the covering resembled the Kleenex tissue box of that era. The Thin Twin pickup morphed into a pickup called the “speed bump,” which had a big rectangular cover so the coil and the magnet could get closer to the string than with the Thin Twin. These pickups were pretty unique.

Which models do you plan to reissue?

The Thin Twin and K162 Pro Bass are currently in production, and after that will be the Jazz II electric guitar—a kind of ES-335-shaped body with a Bigsby—and the Jazz Special Bass. The Jazz Special is sometimes called the Paul McCartney model because he was pictured playing one. It’s basically the 162 morphed into a double-cutaway with an abstractshaped pickguard. It has the same Thin Twin pickup. Following those, we’re scheduled to reissue the Upbeat guitar, which was kind of a poor man’s jazz guitar: It’s an archtop with a big, 17"-wide body, maple-plywood back and sides, a laminated spruce top, and two Kleenex box pickups. They came in one-, two and three-pickup versions, and I think we’re going to do the same. We’re also going to come out with a scaled-down version of the Upbeat called the Pro. At one point it was called the Kay Pro, but when Barney Kessel came onboard in the late ’50s, they started calling it the Barney Kessel Pro. It’s the size of a Les Paul but with a rounded cutaway, and it’s totally hollow. It’s about 2.75" thick and about 12.5" wide, with an arched top and back. You see the originals in stores for around $2,500. We are also planning to bring out three or four Barney Kessel models. I am not sure if we’re going to call them that, though, because we haven’t worked out a deal with his estate yet. After the Pro, we hope to bring out the Barney Kessel Artist, which is one step bigger. It has a 15" body and two Kleenex box pickups. We also want to do the biggest one, the Barney Kessel Jazz Special. It had split parallelogram inlays, a 17" body, and solid woods. It was the top of the line when it was introduced, but it didn’t sell that well because people hesitated to buy a Kay for $400 when they could get a Gibson Super 400 for the same price.

What changes have you made from the original designs?

The originals were made for a variety of house brands. You will see the same guitars under the names Old Kraftsman, Silvertone, and Galliano, with different versions of the headstock. The basic Kay headstock was just the name Kay, sometimes with the metal logo and sometimes with the mother-of-pearl inlay logo. Tony Blair thought he would offer them all with the “Kelvinator” headstock [Editor’s note: The headstock’s nickname comes from the refrigerator-brand logo it resembled.] to tie the whole line together—and to distinguish it from the originals. In the custom shop version, I offer original headstocks as an option. Another change is that we put a one-degree pitch on the necks. Many of the original instruments were unplayable because the necks were pitched flat and tended to rise over the years. Also, from 1953 to 1958 they had no truss rods, but I decided to go modern and put in a two-way truss rod. Also, the necks used to be really big. Though some think the big necks were great, there are only a few people out there that want gigantic necks. We made them smaller, sort of like a 1958 Les Paul. Also, we use a Tune-o-maticstyle bridge instead of the original wooden bridge—which was in the wrong place and made intonation impossible.

With the Thin Twin, we kept the best features of the 1958 version—like the checkerboard binding. Up until that year, they had flat backs, but we went with the arched back that started in ’58, and instead of using a one-piece top, we bookmatched the maple top. The original Jazz II had a bolt-on neck, a floating bridge, and no bracing in the body, so you rarely find one that is completely functional. We ran parallel braces down the middle of the body, set the neck, and put on a fixed bridge. It is now a really great guitar.

kayvintagereissue.com

fritzbrothersguitars.com