|

| For our video interview, plus footage of rare historical pickups and inside the Seymour Duncan factory, click here. |

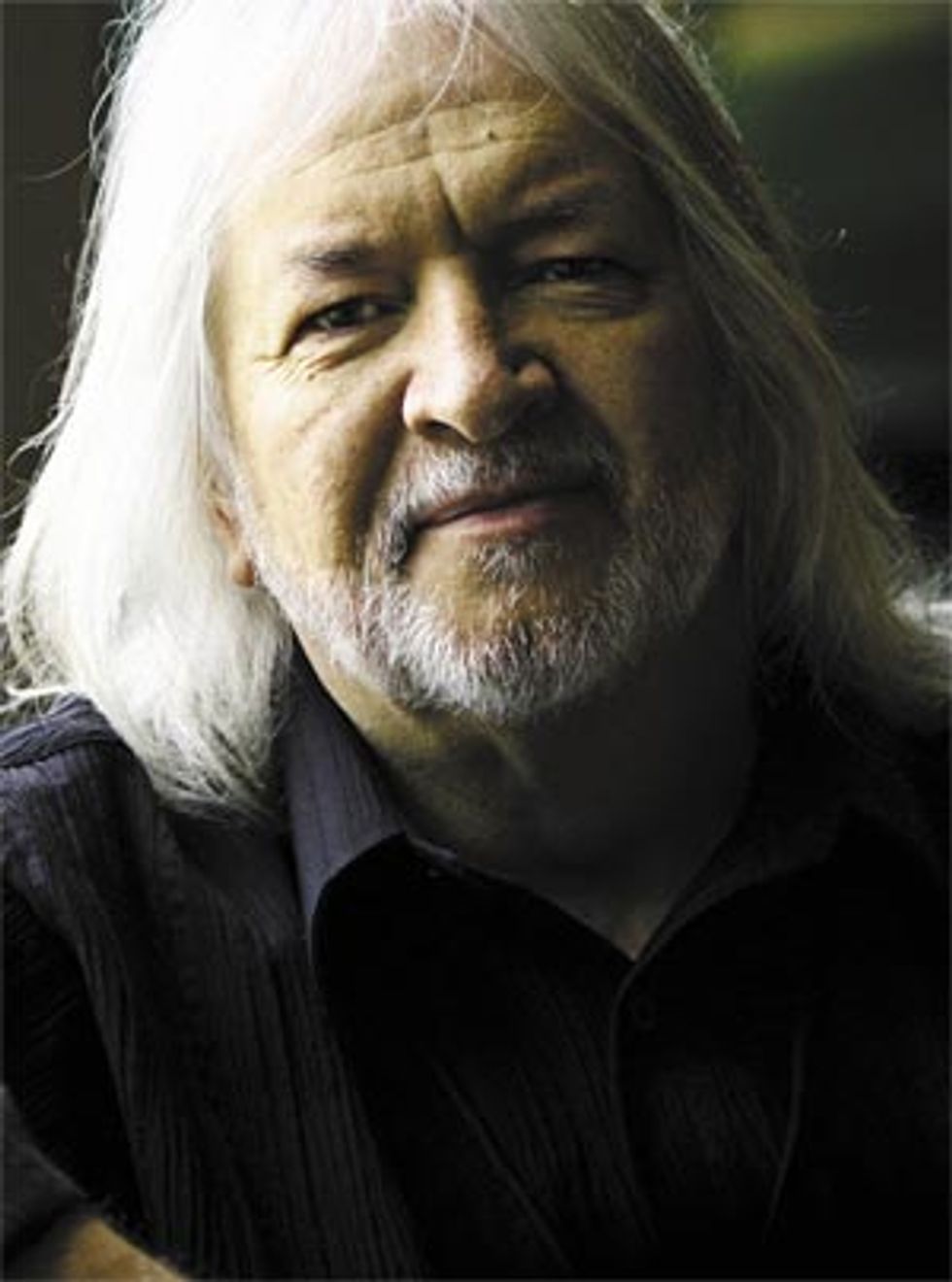

How did you get into the pickup business?

I was about 12 or 13 years old, and someone had borrowed one of my guitars – a ’56 Telecaster – and they got the high E string wedged under the lip [of the pickup]. It was gouged into the coil, so it didn’t work and I had to play all night with just the rhythm pickup.

So the next week, I went to school and took apart the pickup in Biology class because I had microscopes, tweezers and other stuff handy. I started pulling all these fine hairs and pieces of wax off the pickup in an attempt to figure out what the problem was. I’d take the turn off and it would break again.

Because the pickup was so damaged, I ended up taking all the wire off and, luckily, my dad’s brother-in-law noticed what I was doing and helped me out. He took the magnet wire and got me a spool of 42-gauge plain enamel from Philadelphia and I started winding the pickup. My first coil machine was an actual record player that went 33 1/3, 45, and 78 – I just mounted a block of wood and the Tele pickup on it!

Because the pickup was so damaged, I ended up taking all the wire off and, luckily, my dad’s brother-in-law noticed what I was doing and helped me out. He took the magnet wire and got me a spool of 42-gauge plain enamel from Philadelphia and I started winding the pickup. My first coil machine was an actual record player that went 33 1/3, 45, and 78 – I just mounted a block of wood and the Tele pickup on it! At the same time, I was playing on a bill with a band at Tony Mart’s in Ocean City, New Jersey. The band eventually became known as the Hawks – and went on to become the Band and play with Bob Dylan. The guitarist, Robbie Robertson, and I were talking and he said, “Maybe my pickup sounds fatter because I have more turns on it than yours.” I had only a vague idea what he was talking about, because I knew little about pickups at the time.

Les Paul gave you some pointers along the way as well, right?

Yeah, my uncle knew Fred Waring and Paul Whiteman, who were band leaders in the 1930s and 40s, and he eventually took notice to me liking the guitar, so I took a trip with my uncle to Atlantic City to see Les Paul and Mary Ford. After the show, we went backstage and I saw Les’ pulverizer and everything he had on his guitar. I asked Les what the pickup was and how it worked, and he told me.

Later, he talked on a radio show about how he remembers me as a little kid, coming backstage to talk to him and how I now do guitar pickups. I played a tape of the radio show for my employees.

So you started out making pickups just for yourself?

Yes, they were just for my guitars. A few years later, when I was 16 or 17, I was winding pickups with my own machine and repairing old guitars and reselling them. I sold a ’57 Strat for $35! I never imagined that a guitar would be so valuable today – I had dozens of them that I fixed and resold.

There was a place called Landis Music in Vineland, New Jersey that I’d go to after school, and in the back room there was a box full of broken guitars that people traded in – old Strats and Teles – and I started collecting parts and pickups. I would ride my bike to look for guitars that were in the trash and forgotten on Saturday afternoons. It was a great time to be able to do that.

There was a place called Landis Music in Vineland, New Jersey that I’d go to after school, and in the back room there was a box full of broken guitars that people traded in – old Strats and Teles – and I started collecting parts and pickups. I would ride my bike to look for guitars that were in the trash and forgotten on Saturday afternoons. It was a great time to be able to do that. Just by that experience, I started doing things. I went to eight grammar schools, four high schools, two sub-universities and photography schools, and it was hard being the new kid in town. But by the time I was 16 and 17, I was always the new guitar player in town, and that made it easier to socialize when moving around so much. Once you’re in a band it’s pretty easy to meet new people, and it was great. Some of my first customers were local bands from South Jersey.

Was it through these repairs that you gained an appreciation for vintage instruments?

Well, when I moved from New Jersey to Cincinnati, I did repair work for a place called Dodd Music center, but there was another store in Norwood, Ohio called Hughes Music. I’d see all these old guitar parts and once asked Mr. Hughes what he was going to do with so many maple Tele and P-bass necks. He grabbed one of the necks, turned on the bandsaw and cut the neck in three or four places. He used these pieces as starter firewood for his fireplace.

They were warranty necks because the finish was wearing off the fingerboards, and people were trading them in for new ones with rosewood fingerboards. Mr. Hughes had hundreds of necks, and walls and walls of parts. I had a newer Tele and he liked the new stuff, while I liked the older stuff, so I traded him.

The old Tele had all the old ’53 hardware and the serial number on the plate was 1835. At the age of 16, I was already very much interested in vintage. For one, you could find them at a decent price, but it wasn’t just that. Something about the older guitars just really appealed to me.

I watched Roy Buchanan play an old ’53 he called Nancy – I loved that sound. There was another band called the Fendermen who always played their blonde Teles, Strats and P-basses. These were the first bands I saw and they all played older guitars.

| |

|

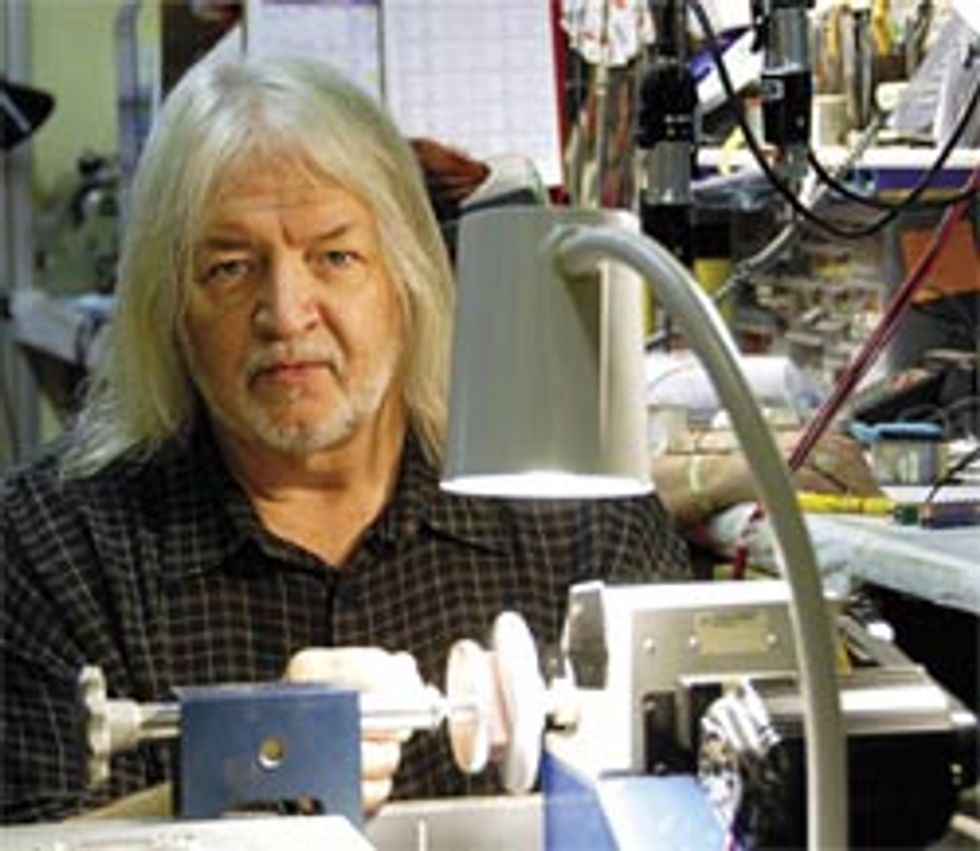

My first pickup was basically a single-coil pickup. I would cut out each pickup and each piece of flatwork one at a time. I also made a router jig, and I would route out each blank part and then drill each hole out. After making some money doing that, I bought a Roper-Whitney punch and made a fixture where I could line up each pole piece and punch out each piece one at a time. I did thousands of hole-punches in bobbins.

What was the first official pickup from the Seymour Duncan company?

Well, my first products were actually Tele pickguards and brass Tele bridges, then knobs and everything else. The first pickup was the SSL-1. We had someone call us from Nashville looking for a vintagestyle pickup – which wasn’t really being made at that point. And I started doing the SSL-1 and STL-1, which was the first Tele pickup. Then, I was doing [pickups for] Duo-Sonics, Jazz Basses and P-basses at the end of 1976 and into 1977.

We got the humbucker mold from the original Gibson molder, so we went to them and were able to get our first humbucker mold made.

Speaking of things like the original Gibson molder, you have in your possession some pretty huge pieces of electric guitar history. Can you tell us about some of these?

I have a number of pickups I received from Seth Lover. There’s a very early prototype of the Staple pickup – he made these prototypes in ‘54-‘55 and used them as a neck pickup on all the custom Les Pauls. They called it the “black beauty” or “fretless wonder.”

And then of course there’s my Holy Grail. It’s the actual pickup used for the Gibson patent, and it was given to me by Seth before he passed away. He just had it in a shopping bag; it’s fabricated like a dog-ear P-90 with the dog-ear mounting ring.

Have you ever heard it?

Oh yes, I’ve heard it. It’s actually pretty bright, but it’s because of the pole structure once it got the adjustable poles and everything.

Another one Seth just had sitting in a box was a ‘58-’59 PAF Double Cream. It’s beautiful. It was made from the old butyrate; it’s a certain grade of butyrate, but I have all the historical data on proper ingredients, temperatures and grade of butyrate that were actually used to make the pickup, and we use that in our recreations of it.

| |

|

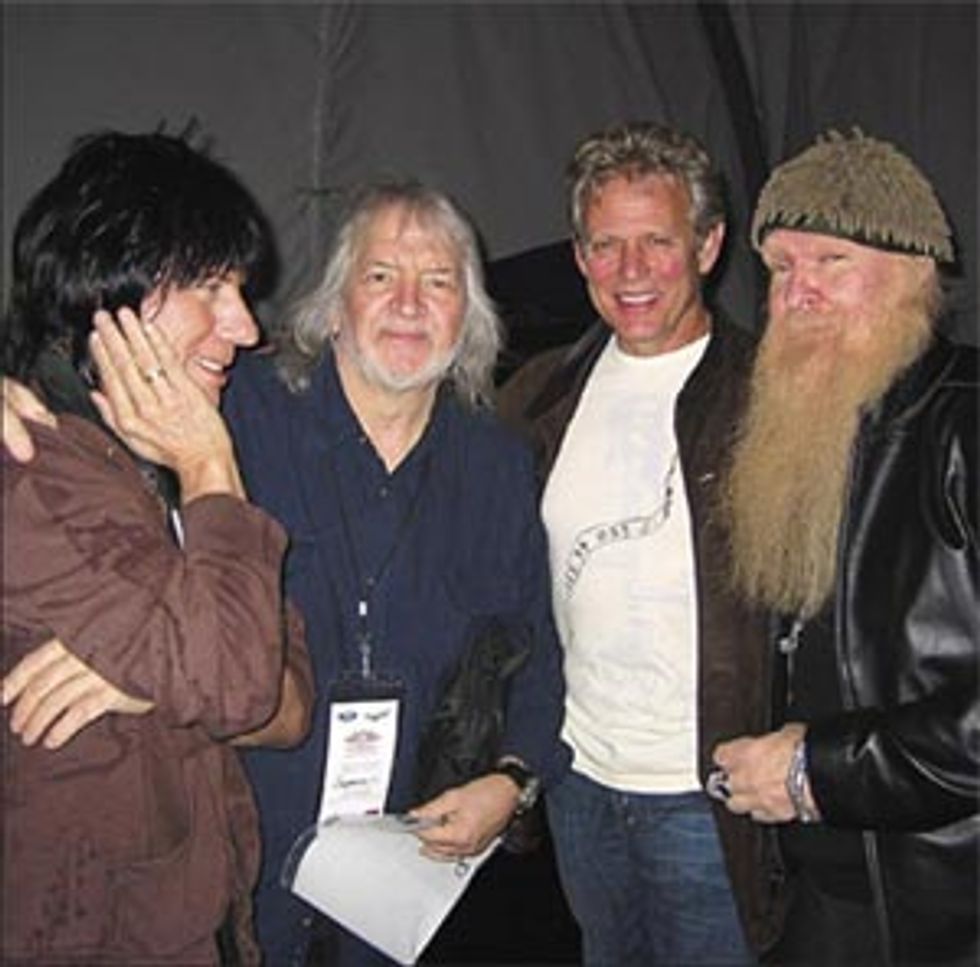

I was doing NAMM shows with my partner Cathy Carter Duncan and Phil Kubicki of K and D guitars. Phil is a brilliant designer and craftsman and builds beautiful instruments.

So we were showing the K and D guitars with our pickups on them during one of these shows in 1976 – when the company was just about to start we were still doing re-winds – and some man came up to me and gave me a business card. He introduced himself as Seth Lover, the guy who invented the humbucking pickup.

Lover set the standard for everything and everyone. We instantly became great friends, and over the years I would go down to his place in Garden Grove, California. We were both into ham radios, so we talked a lot about them and even got on the air a few times and talked to some people in Japan and all over the place. That was so cool.

A lot of times we’d just sit around the kitchen table, and his wife would make tea and biscuits for us. Seth would bring out old articles about amplifiers and prototype pickups he’d done, and then he’d show me the actual pickup used in the patent of the PAF humbucker in 1955. It was pretty amazing to see the beginning of what now is one of the top pickups used by all guitar companies.

A lot of times we’d just sit around the kitchen table, and his wife would make tea and biscuits for us. Seth would bring out old articles about amplifiers and prototype pickups he’d done, and then he’d show me the actual pickup used in the patent of the PAF humbucker in 1955. It was pretty amazing to see the beginning of what now is one of the top pickups used by all guitar companies. I felt very proud when he’d take me into his garage and shop. I couldn’t find anything on the workbenches, but Seth knew where everything was. He’d have boxes and boxes of transformers, and the drawers were filled with Fender parts from when he worked with Fender. The other bins would have all the Gibson parts and he’d often give me a thing here and there.

How did you get all the information on the butyrate formulas and other secrets of the pickups – directly from Seth?

Right before he passed away, he said he had some notes for me and he ended up giving me some of his notebooks with all the drawings and different plastics. I have all the sheets from the plastics that he used to make his prototypes. It’s really pretty neat to have, and some day I may publish a book with all this really cool history in it, with the drawings and everything else. I’m just so proud that he thought enough of me to pass on this history.

| |

|

The company is very proud to be associated with Seth. I was very proud to have him as one of our endorsees of the products we make here. He put his stamp of approval on our products, how we do it, the manufacturing techniques and how we make all our own parts, including bobbins. We stamp out stuff, laser-cut things, use punch machines, etc., while a lot of other pickup manufacturers buy their parts from outside sources and then assemble the parts themselves.

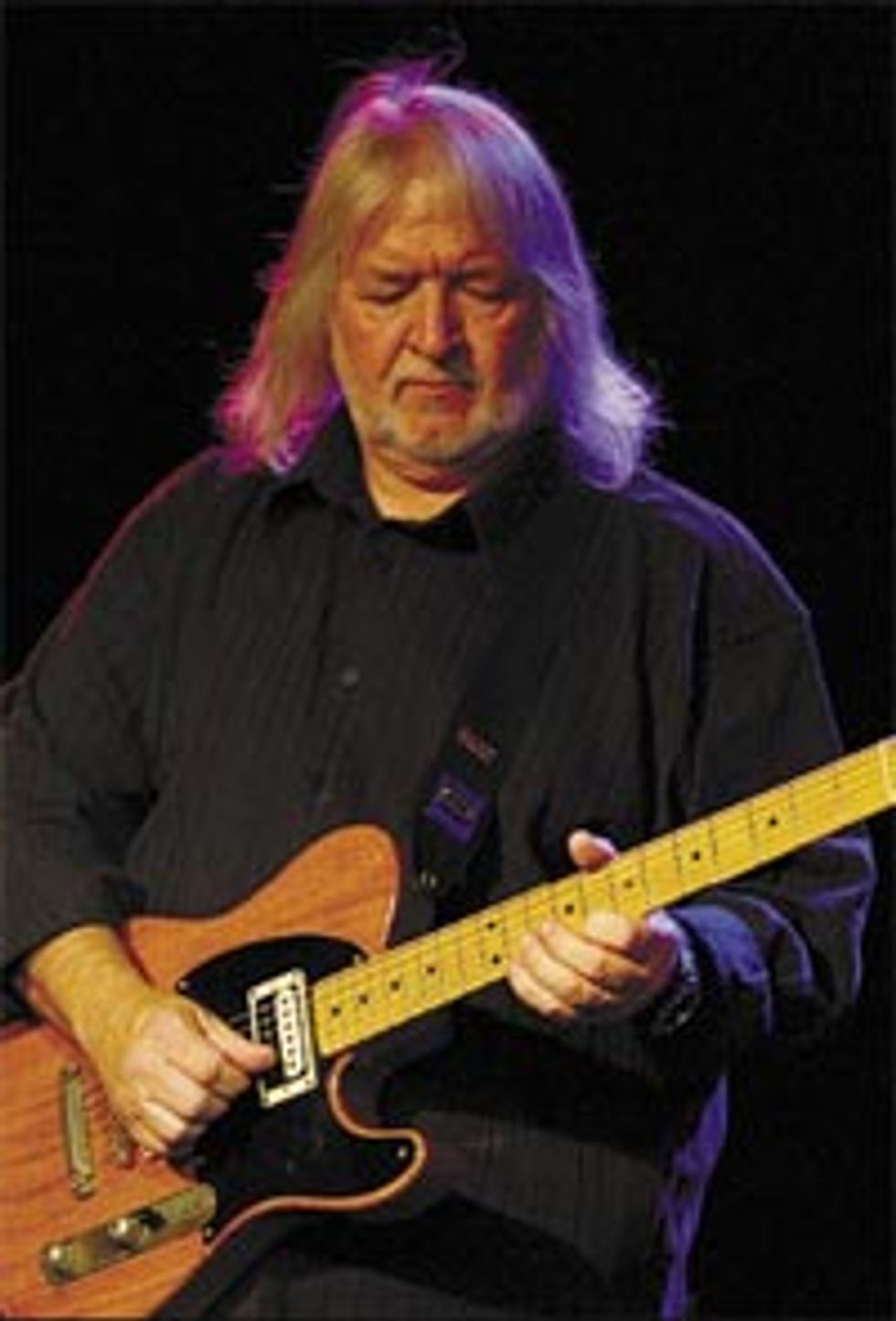

Who are some of the famous guitarists you’ve wound pickups for?

I’ve always really admired Jeff Beck, and when I was in England in 1972, I made a guitar called the TeleGib. It was my first JB and my first JM model. I called the bridge pickup JB for Jeff and the neck JM for John Milner, who was in American Graffiti. He had that little yellow High Boy hot rod and would drag race against Harrison Ford. This was way before I was manufacturing pickups though – these were rewinds that I had done.

I gave the TeleGib to Jeff and he used it during the last days of the BBA, and then used it on the Blow by Blow album. I actually got the chance to introduce Roy Buchanan and Jeff Beck, and for me to be able to do that was really great because they are two of my favorite guitar heroes of all time.

It was neat having Beck dedicate the Stevie Wonder cover, “Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers” to Buchanan on Blow by Blow, and then have Roy eventually dedicate a song to Beck. I grew up watching Roy Buchanan, and I was quite lucky to know him.

It has to feel good that one of your heroes created some legendary songs and tones with your creations.

I mean, it’s their talent, workmanship and tone that makes their songs really work, but when I hear Jeff’s songs he used with the TeleGib – how tasteful the sound is when he used that guitar – it’s a great feeling.

I did prototype Stack pickups for Michael Sembello for the song “Maniac,” and I worked with Buzzy Feiten when he did Full Moon. I worked with Santana in his early days, and I also did some work with Eric Johnson, who is one of my favorite players. I also worked with James Burton. When I was in England, I wound pickups for Golden Earring and they used it on their song “Radar Love.” I also did the neck pickup for Blackie, Eric Clapton’s famous Strat.

So you did all these re-windings for these guys when their other pickups went bad?

Yeah, pickups can go bad when moisture gets in through the exposed poles. I call it ICPC – Inter-Coil Pole Corrosion. It’s when the coil can actually rust and break down the insulation on the magnet wire. If you’ve ever pulled an old sixties Tele pickup that wasn’t waxed, you’d see a lot of rust around the pole pieces when you take the coil off because there are all sorts of ferrous materials in the pole pieces that can actually rust. That’s why it’s good to use the old lacquer and wax, because that’ll help to stop the moisture from permeating.

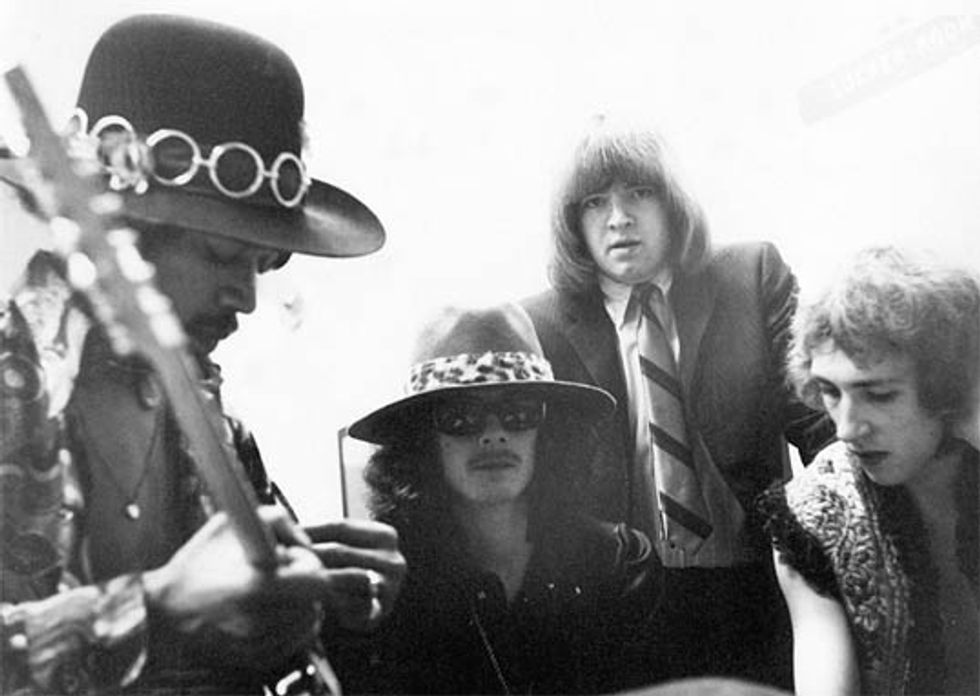

My fondest days, though, were when I rewound a bunch of old Strat pickups for Jimi Hendrix. I gave them to Roger Mayer and he put them into one of Jimi’s white Strats back in 1968. I actually rewound two sets of pickups for Hendrix. If you ever see pictures of Hendrix wearing a black brim hat with the rings on it, that’s the era I was working with him.

Actually, it’s funny – during that time, Jimi bought a ’62 or ’63 Jazzmaster, and I took photos of him with it. Two years ago, I get this call from Steven Segal asking if I knew something about a guitar he just bought from the Hendrix family – it was Jimi’s old Jazzmaster. Steven wanted to know for sure, so he came up here with his entourage, and I knew at first glance it was Jimi’s, but we compared the guitar with the photos and confirmed it.

Back in Cincinnati, I was playing at this club called the Mug Club and this guy would come in and sit with me – we were the only guys in Cincinnati (that I knew of) that could play Yardbird songs. The other guy was Joe Walsh, and this was right before he got into the James Gang. We were out there playing and we’ve been friends ever since. He actually was the one who originally got me more interested in ham radio! For me, all those guys were a lot of fun and an honor to work with.

| For our video interview, plus footage of rare historical pickups and inside the Seymour Duncan factory, click here. |

Seymour Duncan

seymourduncan.com