Photo By Sol Allen

Photo By Sol AllenSeeing neo-soul band the Roots on tour is entirely different from what you see during their main gig as the house band for Late Night with Jimmy Fallon or when they’re collaborating with pop titans like John Legend. Performing live as a stand-alone entity, the eight-member outfit led by famed producer Questlove (drums/vocals), Black Thought (MC), and guitarist “Captain” Kirk Douglas shows mad diversity—everything from schizophrenic jazz stylings to deep, hip-hop-tinged grooves, strutting funk, and ripping rock jams. It’s safe to say the Roots could solidly back virtually any act, given that they’ve done so for everyone from Jay-Z to Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, Elvis Costello, and Fall Out Boy. Needless to say, the group possesses a dynamism that few can match, and over the course of their career they’ve managed to evolve while still playing from the heart and remaining true to the music that inspires them. And that’s why the Roots is largely responsible for both a renaissance in, and a major re-imagining of, soul music.

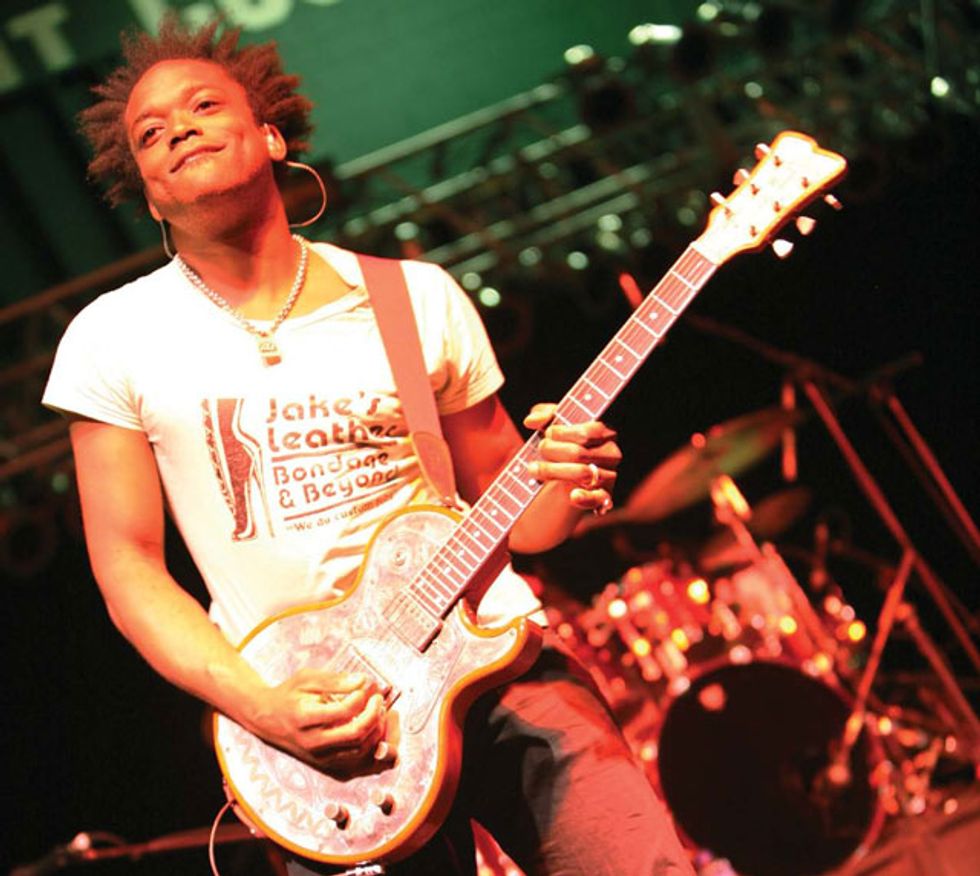

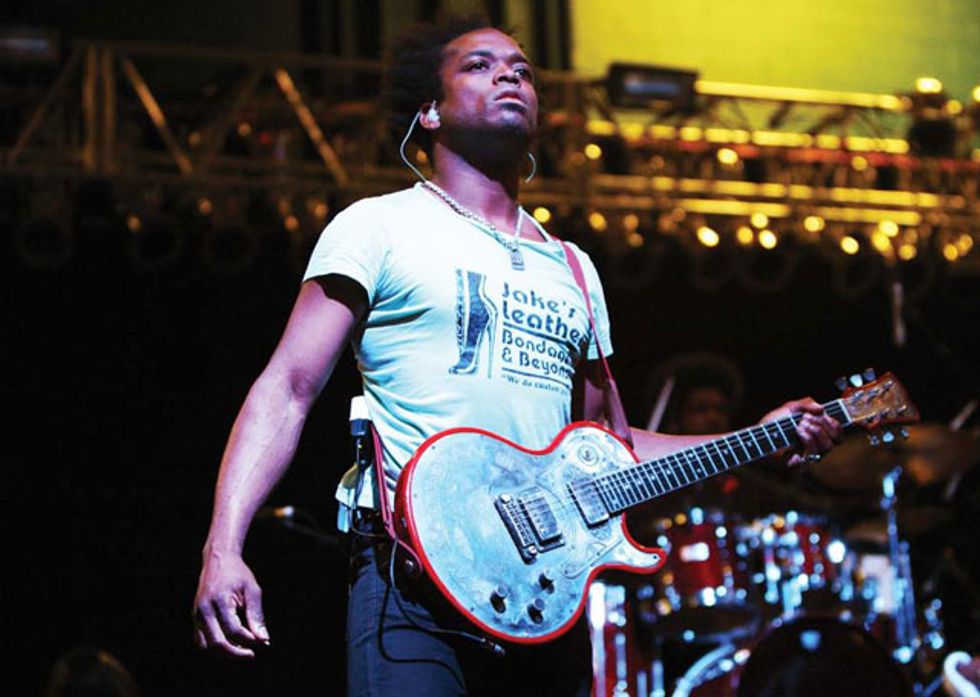

Kirk Douglas, looking

happy during the

University of Vermont’s

Springfest 2011.

Despite losing partial

power, the Roots

packed the school’s

gymnasium. Photo by

Jennifer Murtha

Kirk Douglas, looking

happy during the

University of Vermont’s

Springfest 2011.

Despite losing partial

power, the Roots

packed the school’s

gymnasium. Photo by

Jennifer MurthaJust as you’d expect from such a diverse band, each member of the Roots has kaleidoscopic musical interests. As a budding preteen guitarist growing up in New York, Douglas was simultaneously influenced by funk forefathers like James Brown and rock icons like Kiss and Van Halen. The self-professed Led Zeppelin devotee rocks a prototype of a Jimmy Page signature Les Paul—same relic’ing and all. Douglas performed with the Dave Matthews Band prior to joining the Roots permanently in 2002. Apart from the Roots, he plays in a very different vein with his side project, Hundred Watt Heart.

Douglas is a hard player to explain— though in the best way, because you can’t pigeonhole him. His role in the Roots takes him from picking über-nuanced, barely there background riffs to cranking out fiery, 10-minute jams and incredible call-and-response solos where he scats phrases into the mic and then mimics them on guitar.

Between rehearsal sets for a performance backing Johnny Gill on Fallon, Douglas recently chatted with Premier Guitar about the Roots’ first concept album, Undun, his more rocking Hundred Watt Heart repertoire, and what it’s like to be a cutting-edge funk revivalist with serious chops.

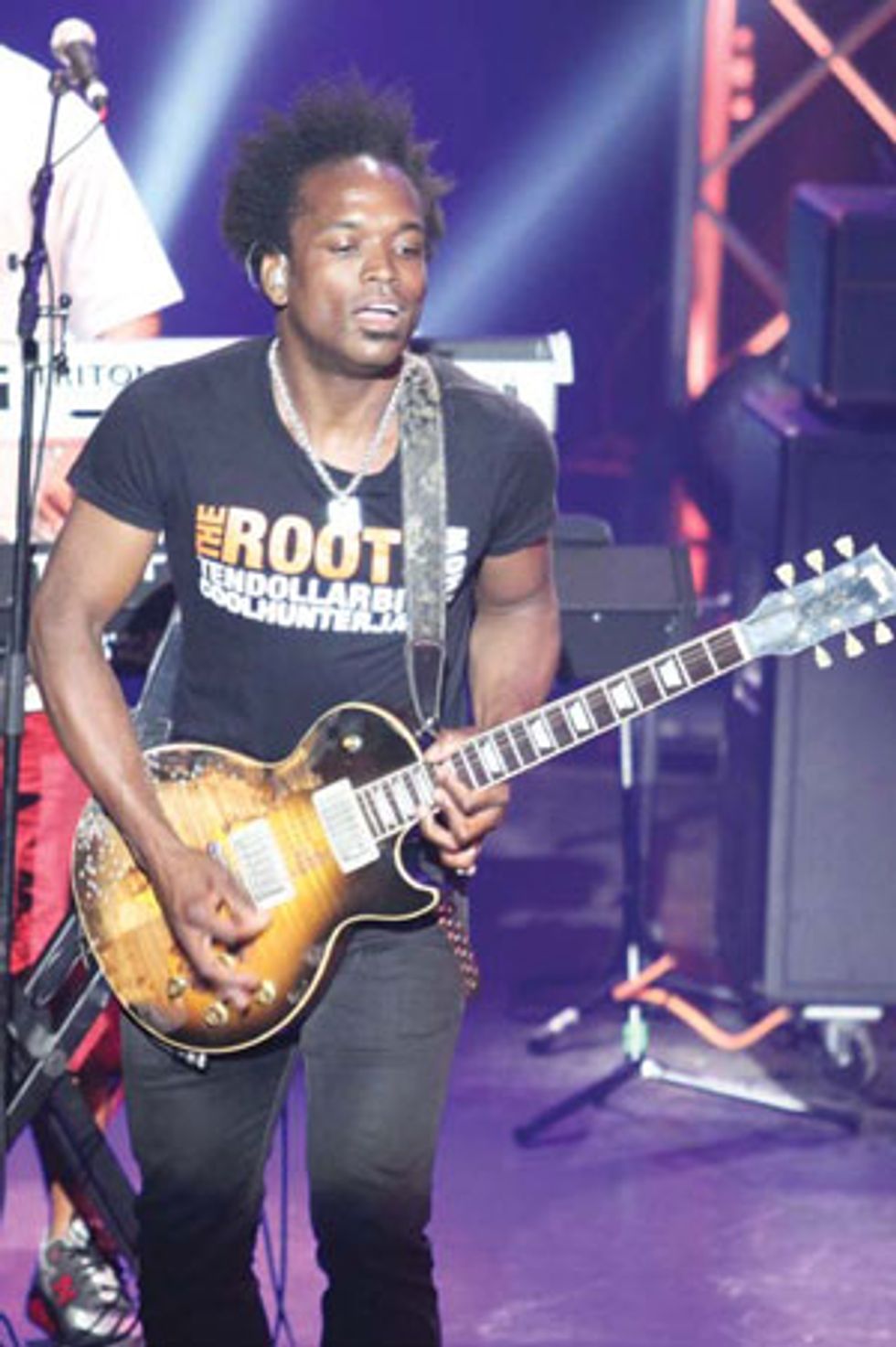

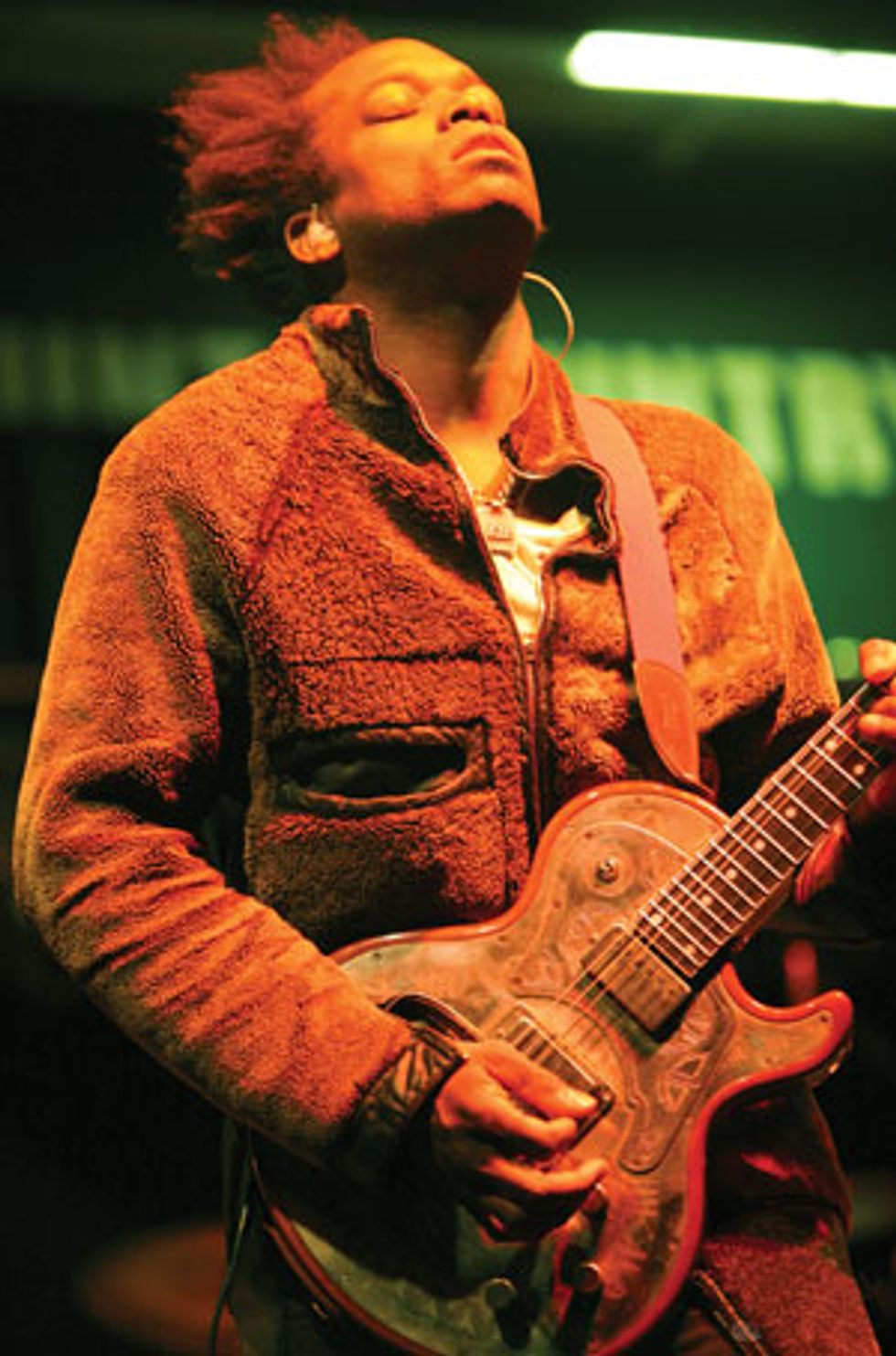

Douglas channels

the funk at the

Marquee Theatre in

Tempe, Arizona, in

October 2008.

Photo by Sol Allen

Douglas channels

the funk at the

Marquee Theatre in

Tempe, Arizona, in

October 2008.

Photo by Sol AllenHow did you first get into playing guitar?

I had a close friend in the second grade

whose older brother was into a lot of

heavy music, a lot of rock ’n’ roll. A lot

of Kiss and Van Halen. I guess I was

attracted to that because, when you’re 7

or 8, you’re interested in superheroes. And

just the sound of the guitar—it sounded

so powerful, and the guitars looked so

incredibly cool. So there was really no

escaping that attraction to the guitar.

And their tunes were catchy, as well.

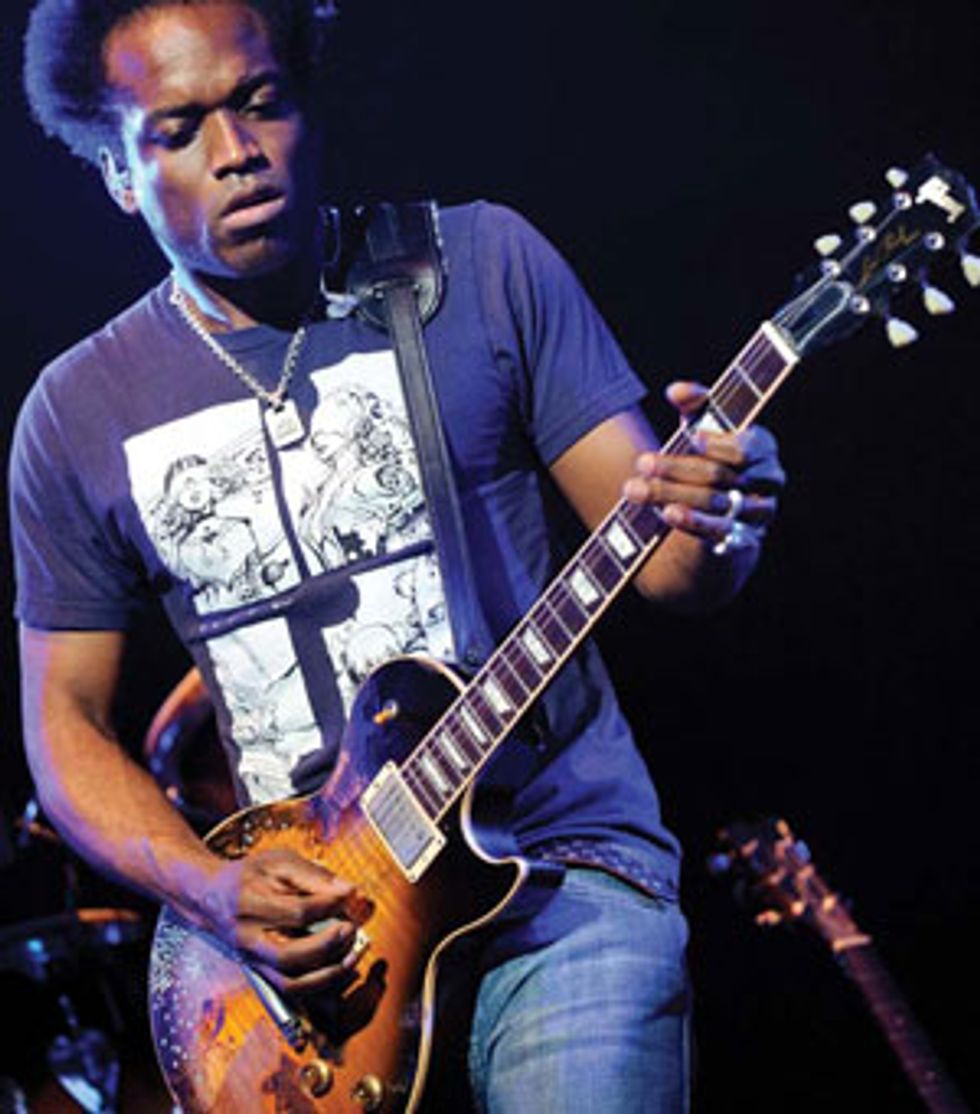

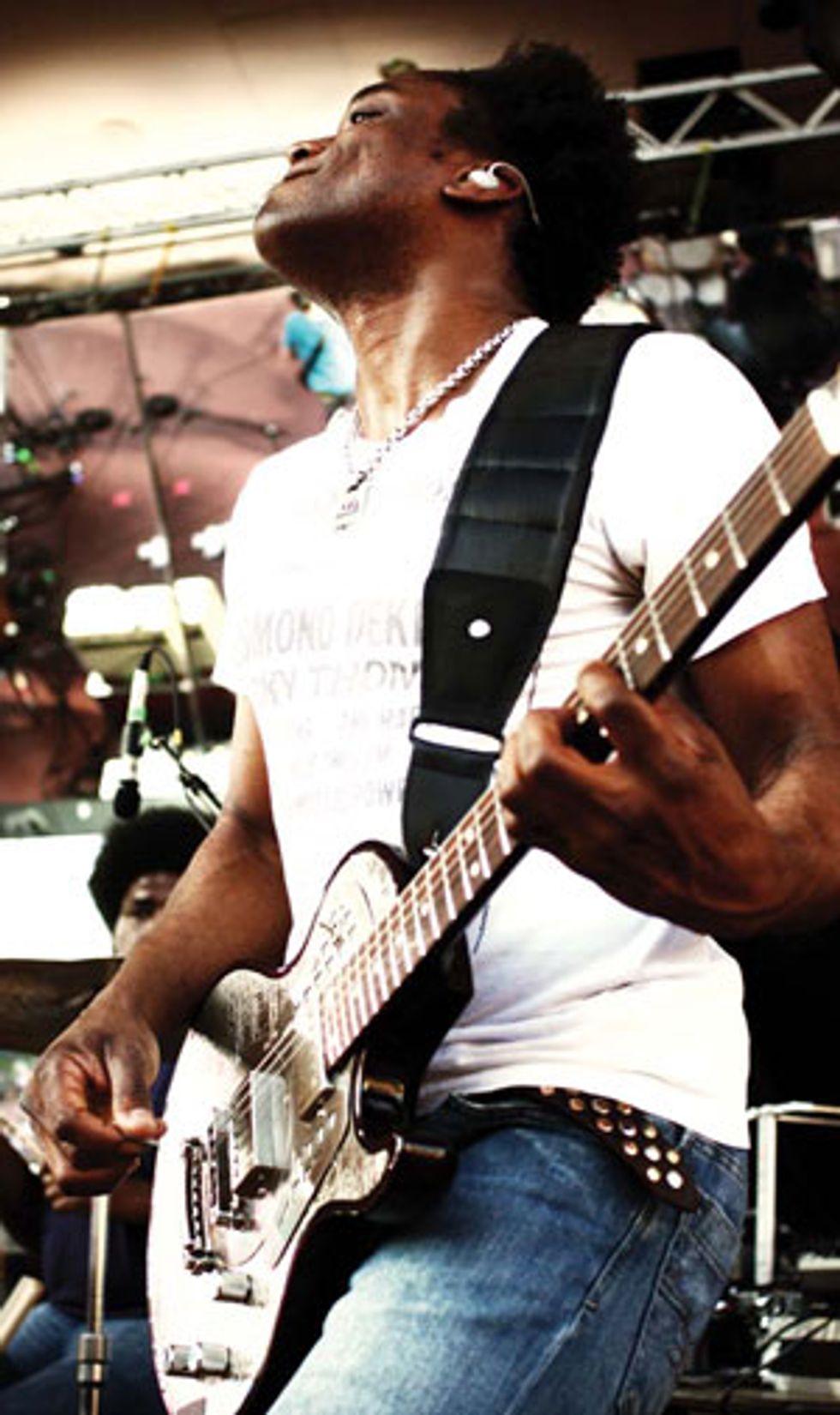

Captain Kirk plays his burned Les

Paul (signed by its namesake) with

the Roots at Montreal Jazz Fest 2011

(keyboardist James “Kamal”

Gray is in the background).

Photo by Rebecca Dirks

Captain Kirk plays his burned Les

Paul (signed by its namesake) with

the Roots at Montreal Jazz Fest 2011

(keyboardist James “Kamal”

Gray is in the background).

Photo by Rebecca DirksThe Roots’ founding members

Questlove and Black Thought have

formal music training. How about

you—would you say music theory has

a place in your playing, or are you

more of a gut-level player?

I’m definitely playing by instinct. In high

school, I gravitated toward jazz band. I

got into Prince, and there was a vacant

seat in the guitar position in the jazz

band. They asked if I’d play with them

and I accepted, but I would really play

mostly by ear. I guess I had that situation

when I was younger, too, when I

had formal training. I couldn’t help but

memorize the things I was learning to

sight-read. And that would just continue

by muscle memory and the combination

of how things felt and sounded. Of

course, theory plays a part when you’re

coming up and learning how scales

connect—majors and minors and the

modes—but I guess I sort of just modified

them for my usage.

Although Undun is a little bit different

for the Roots—it’s your first concept

album—what’s the songwriting process

usually like for you guys?

The way the Roots operates in the studio

and in a live format is completely different.

We stretch out more, live—we’re putting

on a show. The album is a more cerebral

experience. The studio itself is a member

of the band. We’ve gotten more collaborative

as a result of doing The Jimmy

Fallon Show, and that’s made us more of a

cohesive band and created an opportunity

for real-time interaction to make its way

onto the record. But still, at the end of the

day, to put together a cerebral experience

for the listener, the studio itself is more of

a member of the band.

So are you saying that being able to create

a vibe with various studio treatments

is just as important as the instrumentation?

For instance, Undun is very atmospheric,

with lots of piano and strings.

Yeah, I mean, it’s whatever suits the song.

The guitar is very sparse on this album, but

it’s the end product that’s most important—

there are so many other opportunities

for me to get my playing out.

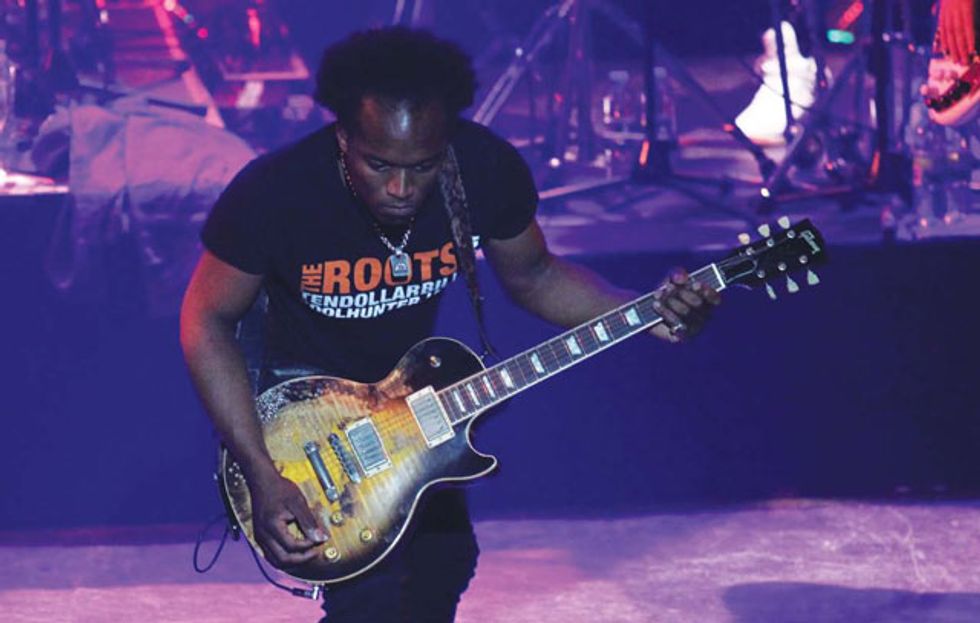

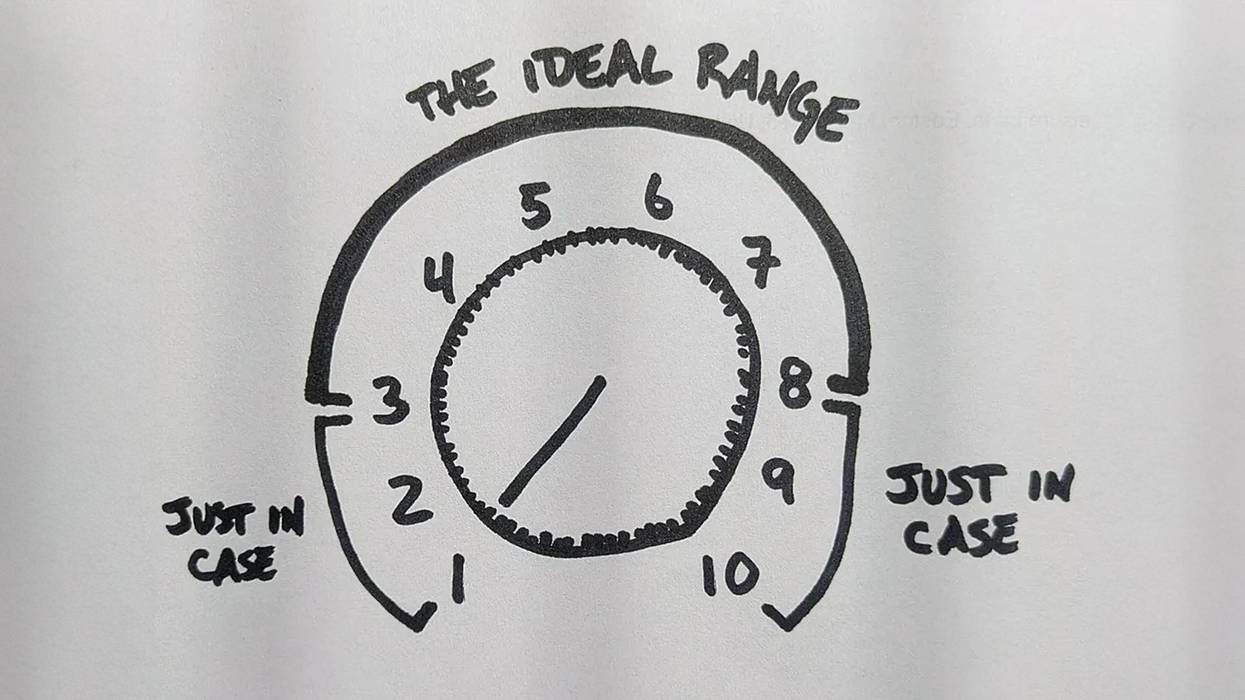

Captain Kirk, guitarist for

the Roots, says he likes to

wear Puma sneakers while

performing because they

make it easy to dial in killer

effects. Photo by Sol Allen

Captain Kirk, guitarist for

the Roots, says he likes to

wear Puma sneakers while

performing because they

make it easy to dial in killer

effects. Photo by Sol AllenThe Roots has a new bassist, Mark

Kelley, who has been onboard a few

months now. As far as writing guitar

and bass parts, what’s the dynamic like

between you two?

A large part of what the Roots is now

is being a house band for Fallon. The

time we spend onstage together, where

the audience pays to see the act the

Roots and the Roots alone, that’s sort

of the past. So when we do a show

where people are paying to see the

Roots only, that’s a very special evening.

But we’re writing all the time—every

time we go to commercial, that’s an

original composition.

What are those writing sessions like?

Well, for instance, right now Questlove

is sick, so he’s out from the Fallon show

for a week. So Frank Knuckles, our percussionist,

is writing the set. It’s a very

well-oiled machine, as far as coming up

with stuff at the drop of a hat. Because

the only intent is to take us in and out

of a commercial, we don’t feel like we

have to change the world with every

piece of music we write. But because that

pressure is lifted, you can come up with

some really cool stuff—because we all

want to make stuff that we enjoy playing.

By virtue of that, sometimes really

good stuff happens, and sometimes that

stuff also finds its way onto albums.

What’s it like to jam with so many

great musicians?

It’s fun. Work can definitely be a box of

chocolates. Yesterday, we were the backing

band for Hunter Hayes, a fantastic

guitarist/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist

who’s, like, 20 years old and a formidable

player. I only heard about him through the

show. I went on YouTube to check him out

and saw that he’s already played the Grand

Ole Opry, and he’s got a big hit that we

backed him on yesterday. But I only found

out about that from being in the Roots and

being on Jimmy Fallon. That sort of scenario

happens pretty regularly. You get to see

people’s fingers up close— all these people

like John McLaughlin. It really enriches

your musical experience.

Percussionist

Frank Knuckles

and MC Black

Thought wax

while Captain

Kirk looks on.

Photo by

Tim Fortner

Percussionist

Frank Knuckles

and MC Black

Thought wax

while Captain

Kirk looks on.

Photo by

Tim FortnerWhat are some of your favorite performances

so far?

Springsteen, definitely. I get chills just

thinking about that. Playing “Late in the

Evening” with Paul Simon was magical.

We played with Tom Jones. We’ve played

with Jimmy Buffett, Todd Rundgren, Elvis

Costello. All of those had an element of

magic to them.

The Captain

makes his custom

Les Paul sing at

the Fox Theatre in

St. Louis. Photo

by Todd Owyoung

The Captain

makes his custom

Les Paul sing at

the Fox Theatre in

St. Louis. Photo

by Todd OwyoungWhich situations were the most surprising

or difficult?

We played a piece with Mos Def called

“Casa Bey” that was more complex than

what you would expect from a hip-hop

artist. When we collaborate with hiphop

artists, they tend to be repetitive,

loop-based things. But when we did this

with Mos Def, it was sort of a The Rite of

Spring-like arrangement. There were a lot

of parts, and we’re not reading when we’re

up there [on air], so you have to do a lot

of memorization. It’s a best-case scenario

to play things many times to get it in your

head and in your fingers, but sometimes

you don’t have that opportunity. So it

requires a lot of focus.

Let’s talk about your weapons of choice a

little bit.

With the Roots, I use Mesa/Boogie amplifiers.

They’re just very versatile, sort of like a

Swiss Army knife, but without getting into

the digital world—which I’m not opposed

to, but I just haven’t gotten around to it yet.

I like the feel of tubes, and I’ve just found

a situation that works for me and allows

me to worry about other things. My setup

is extremely basic: I use a Dunlop Jimi

Hendrix Wah, an Ibanez Tube Screamer, a

Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, and a Maxon

Phase Tone.

Yes, there is stomping in hip-hop. Douglas

puts his foot down at the 2011 Montreal

Jazz Fest. Photo by Rebecca Dirks

Yes, there is stomping in hip-hop. Douglas

puts his foot down at the 2011 Montreal

Jazz Fest. Photo by Rebecca DirksWhen I’m not playing with the Roots, I do a much more guitar-centric thing. I have a band called Hundred Watt Heart, and I use Divided by 13 amps with that. I really like the feel of just using one amp. With the Roots, I’m required to play clean a lot of the time, so I’ll use different channels. I’ll have my cabinets turned around, too, because a loud guitar is not favorable in a hip-hop band.

Although you guys have done a

“Machine Gun” cover that was pretty

guitar-intensive.

It totally has its moments in the show,

don’t get me wrong, but it’s not like going

to see the Mars Volta. That’s way more of

a guitar experience, where the guitar takes

up a lot more real estate in the bed of the

music. Because of that, I definitely have a

need to play music on my own that’s more

guitar-centric.

Douglas and Damon “Tuba Gooding

Jr.” Bryson catch a vibe during the

University of Vermont’s Springfest

2011. Photo by Jennifer Murtha

Douglas and Damon “Tuba Gooding

Jr.” Bryson catch a vibe during the

University of Vermont’s Springfest

2011. Photo by Jennifer MurthaI’ve watched some YouTube videos of

you playing 10-minute solos where

you accompany yourself vocally. Is that

something you do more on your own

or with the Roots?

It’s a cool effect—like an organic way

of playing through a talk box. I’ve done

that with the Roots mostly, but last

week I did my first gig in five years at

Brooklyn Bowl, and it was just me and

my band. I wound up having to do two

sets, because Questlove was supposed to

DJ later that night but he got sick. So we

had original music planned for the first

set, but when I realized we had to do

two sets I could either say, “Sorry, we’re

not prepared to do that,” or I could rise

to the occasion. That required us to do

some covers and a lot more jamming and

fleshing-out of things.

Captain Kirk takes

a moment to savor

the tone coming

from his Trussart

SteelTop. Photo by

Jennifer Murtha

Captain Kirk takes

a moment to savor

the tone coming

from his Trussart

SteelTop. Photo by

Jennifer MurthaI never thought I would be doing all of that scatting stuff that I learned from watching George Benson, but as far as stretching out and seeing where you can take the music, I found myself doing that and it felt really comfortable. But that’s something that I learned by playing with the Roots. “Here’s your guitar spot—do what you want with it.” I tried it one night just for the hell of it. A while later, Questlove said, “You know, you stopped doing that scatting thing. You should do that.” And I was like, “Oh, okay.” Sometimes just a little positive reinforcement can go a long way.

The Roots’ jazzy, improv vibe gives guitarist

Captain Kirk Douglas the space to solo and

scat in the vein of one of his influences,

George Benson. Photo by Jennifer Murtha

The Roots’ jazzy, improv vibe gives guitarist

Captain Kirk Douglas the space to solo and

scat in the vein of one of his influences,

George Benson. Photo by Jennifer MurthaGeorge Benson is featured in this issue

as well.

He sat in with us, too, and I told him,

“Y’know, I feel like I owe you a lot of money

for that scatting-and-playing thing I do—I

totally ripped that off from you.” And he’s

like, “Well, son, you better pay up then!”

Let’s go back to your guitars for a second.

Is the Gibson CS-356 your primary guitar?

I use that mostly with Fallon. I got that

guitar when I got that gig. My primary

guitar is a Les Paul that got burned during

a Heineken commercial. I use that one a lot

with the Roots when we go on tour.

And you had it signed by Les Paul, right?

Yep, it’s signed by Les Paul on the back.

But my main guitar is a white ’61

Epiphone Crestwood—that’s probably

what you saw on that Hendrix stuff. For

Hundred Watt Heart, that’s my favorite. It

just feels so good, and it’s got mini humbuckers

so the sound isn’t as thick. It’s not

like thick magic marker—it’s more like

crayon. When you’re using a distorted amp,

the Crestwood offers more string-to-string

clarity on complex chords.

Guitarists can typically be pretty closed minded about hip-hop—they tend to lump it all together in a very narrow niche and stereotype it as dominated by crappysounding drum machines or repetitiveness and inane rhyming. What do you have to say to players who might not have an open mind to your style of music?

Captain Kirk playing

his Trussart SteelTop

at Mesa Amphitheatre,

Mesa, Arizona in 2008.

Photo by Sol Allen

Captain Kirk playing

his Trussart SteelTop

at Mesa Amphitheatre,

Mesa, Arizona in 2008.

Photo by Sol AllenWhen you’re looking at the roots of hip-hop, you’re looking back at James Brown—that’s like the original hip-hop. The dude was generally rapping a lot of the time. You could say the same for Dylan and a lot of his stuff. He’s storytelling— he’s rapping. Listen to, “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” Listen to “The Big Payback.” That’s like rap before rap existed. So if you’re dismissive about hiphop, then you’re being just as dismissive to forefathers like James Brown, Johnny Cash, and Bob Dylan.

There’s a lot to learn from hip-hop, too, and I’m really grateful that the Roots saw a relevance in what I was doing and found a place for me in the band. Before I joined, I had cassette tapes with Stevie Wonder, James Brown, Sly and the Family Stone, and the Roots all on one tape. I saw a continuum from what all those people were doing to what the Roots were doing. The fact that we’re doing what we’re doing now and seeing this steady progression of exposure and success makes me feel I was right in seeing that.

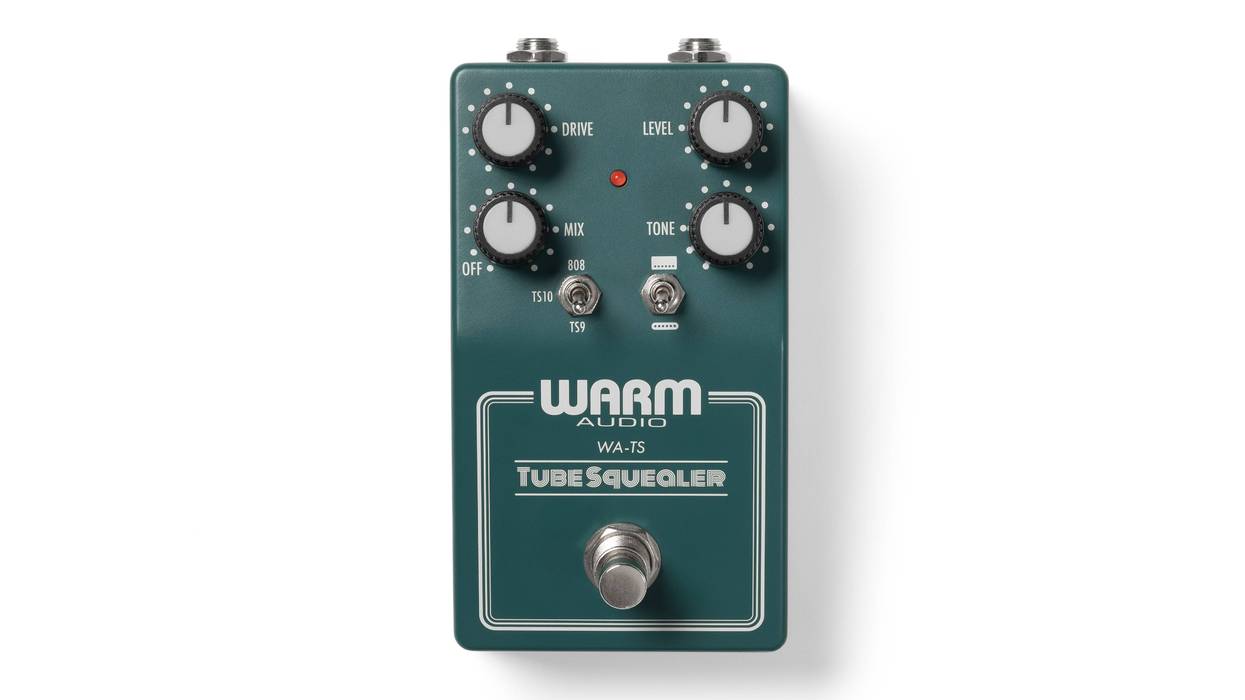

Captain Kirk's Gear

Guitars

’61 Epiphone Crestwood,

various custom Les Pauls

(including a Jimmy Page prototype),

Gibson CS-356, ’69

Gibson SG Custom, James

Trussart SteelTop

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Stiletto Ace

(on Late Night with Jimmy

Fallon), Mesa/Boogie Lonestar

Special (with John Legend),

Divided by 13 amps (for

Hundred Watt Heart)

Effects

Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer, Durham Electronics

Sex Drive, Maxon PT999 Phase Tone, Empress

Tremolo, Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, Dunlop

Jimi Hendrix wah, original MXR Phase 45, Boss

TU-2 Chromatic Tuner

Youtube It

Watch “Captain” Kirk Douglas unleash seriously soulful tones in these high-octane live performances.

This clip showcases Douglas’ screaming, Hendrix-style chops.

This particularly bluesy groove sees Douglas backing Robertson on

guitar (with some shine from Robert Randolph) and adding impressive

vocal harmony to a song from Robertson’s How to Become Clairvoyant.

Captain Kirk shows his edgy side to vocalist Estelle with a calland-

response breakdown, even wrapping his, er, guitar around her.

With a huge nod to George Benson, Douglas scats along to his own

versatile picking.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)