If you're a shredder who's into Yngwie Malmsteen, you probably think Eric Clapton is the slow player. If you love Clapton's lightning-fast performance of "Crossroads" from Wheels of Fire, you might believe Robert Johnson's original version (properly titled "Cross Road Blues") crawls along a little faster than a hyper turtle. And if you can't wrap your mind around Johnson's dexterity with the slide, perhaps Brij Bhushan Kabra's meditative Indian slide playing on Call of the Valley is more your … speed. And, at the risk of waxing philosophical, consider that an open 5th-string A vibrates at 110 Hz a second. Well, that's still pretty fast by almost any standard! In this lesson we'll keep in mind (with all due respect to Einstein) this relativity, and approach "slower" from a variety of angles.

Sustain

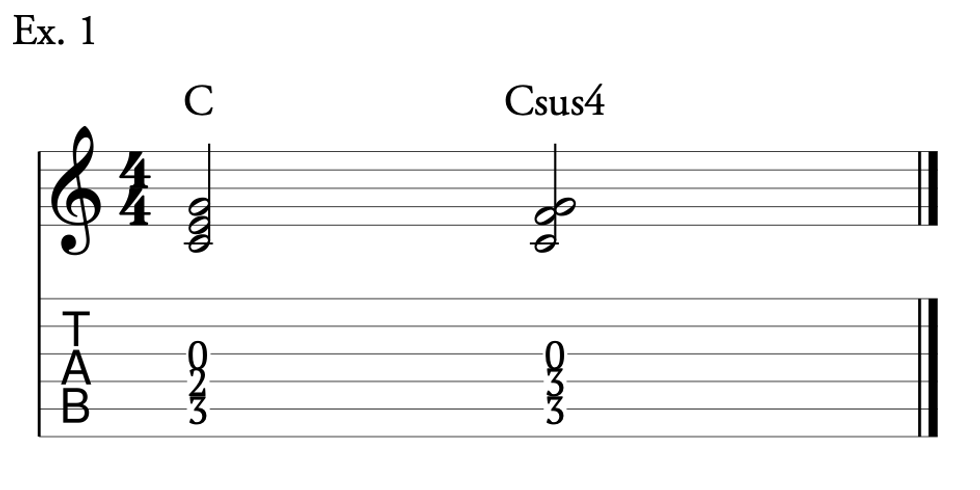

Besides resting (which we'll get to soon enough), the slowest and most engaging way to play a note is to sustain it. There are few more skilled at this than Carlos Santana. On his live version of "Europa" from Viva Santana, Carlos manages to sustain a note for just under one minute (check out the video below starting at 3:36). And though it's true that the band is playing an upbeat Latin groove over a two-chord vamp, it's Carlos' painstakingly sustained note that creates the tension and sense of excitement. Ex. 1 is a Santana-esque groove featuring several sustained notes, including one long-held bend.

Ex. 1

Europa - Viva Santana version!

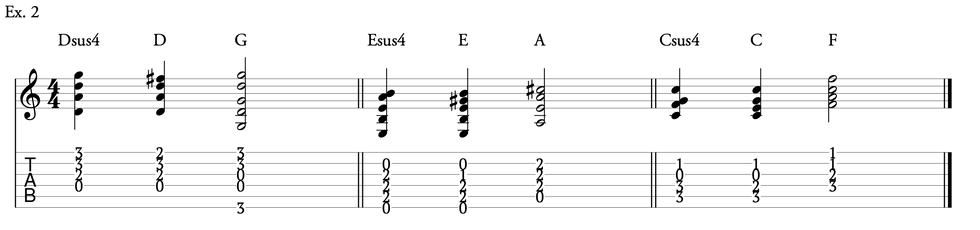

While Santana proves that you can do a lot with just one note, there are plenty of multiple-note variations you can create from a sustained, vibrating string. When it comes to this approach, one immediately thinks of Jimi Hendrix and his live performances of "Machine Gun," "Wild Thing," and "The Star-Spangled Banner." My favorite Hendrix sustained note can be heard on his version of "Auld Lang Syne" from Live at the Fillmore East, which he recorded on New Year's Eve of 1969. In this stellar performance, Jimi sustains a note for more than 10 seconds then proceeds to perform the melody without ever picking the strings, using only his whammy bar and a series of slides. Ex. 2 is an imitation of Jimi's performance using hammer-ons and pull-offs instead of whammy bar technique.

Ex. 2

In the aforementioned songs, both Santana and Hendrix would have been playing through amplifiers with the volumes completely cranked. While this approach is fun, today you have several options when it comes to performing such long, sustained notes. Countless compressors, actual "sustain" pedals, and digital modeling amps will allow you to play with minimal volume and still achieve infinite sustain. Experiment with different setups to decide what is best for you in any given situation.

Space

A second approach to playing slower, and one that can be achieved with or without amplifiers, is the simple act of resting between phrases, or more dramatically, between the notes that make up your phrases. Now I say "simple," but if you were to listen to any number of guitar recordings you might wonder, "If it's so simple, how come so few do it?" It is true, guitar players do seem to have an aversion to resting and creating space in their playing. Still, whether this is out of habit, imitation, or thoughtlessness, the solution is simple.

To get comfortable with this approach, listen and imitate vocalists who, unlike guitarists, have to breathe between phrases. A good place to start with vocal mimicry is the study of any number of versions of W.C. Handy's "St. Louis Blues," a standard 12-bar form that features a more lyrical and less lick-based melody. Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Etta James all have recorded versions of this blues standard and, notably, Etta's version begins with a bold a cappella introduction that all musicians could stand to learn from.

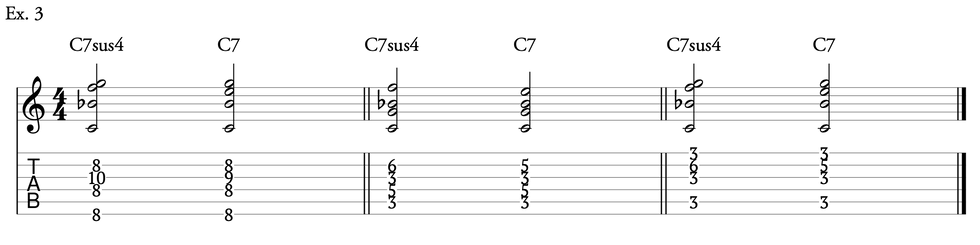

Ex. 3 features acoustic and electric versions of two choruses of "St. Louis Blues." The first time through the melody is performed almost identically to the original 1914 sheet music. While this version does have a fair amount of space, the phrasing is rather dull rhythmically. The second chorus adds even more space (resist the temptation to fill the six beats rests at the end of each phrase), is more syncopated, and breaks up each individual lyrical sentence with rests in between words, rather than stringing the lyrics together in one long phrase.

Ex. 3

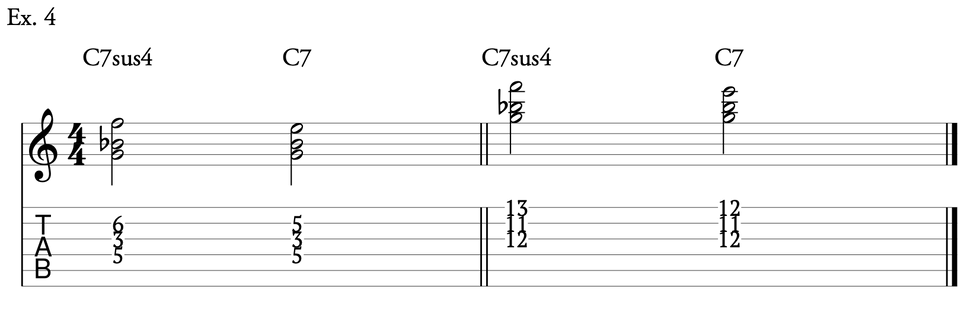

There, are of course, myriad other paradigms of vocal phrasing that highlight the use of space and that also translate well to the guitar. Ex. 4 borrows heavily from Patsy Cline, who was particularly adept in her use of space and timing, often pausing unexpectedly and then twisting her notes into a surprising series of syncopations that few other musicians would have considered. It starts with a very straight, Fake Book-style delivery, then reveals how Patsy might vary a repeated phrase with her use of space, articulation, and rhythmic variation, similar to the verses of "Crazy."

Ex. 4

Refinement

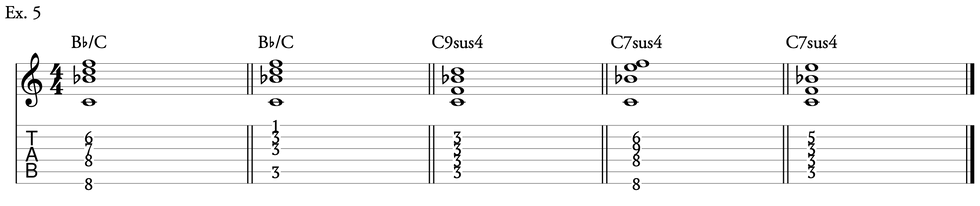

One of the numerous benefits of playing slower is that it can underscore the subtler aspects of one's guitar technique. By performing an attack or articulation gingerly, the art can be heard in both the procedure and the musical result. Jeff Beck is a master of this type of slow playing, and his 1976 recording of Charles Mingus' "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" is the archetype performance. Ex. 5 takes many of the slow articulations Beck uses in "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat"—measured bends, circumspect slides, deliberate rakes, even the elusive click of switching pickups—and applies them to "Amazing Grace," which Beck has also recorded, though with a different approach and, ironically a, slightly faster tempo than presented here.

Ex. 5

Solo

Legions of fingerstyle guitarists are under the impression that, because they're playing solo, they must play all the usual parts at once and it must be rhythmically relentless. As a result, far too much fingerstyle music is one-dimensional. Not so for Leo Kottke's music. Though Kottke is notorious for playing more notes in one song than most guitarists perform in 10, he also has pieces that he delivers with a leisurely approach: "Three Walls and Bars," "Parade," and "Easter" are all prime examples. Ex. 6 is an homage to Kottke's more relaxed compositions. It features an amalgamation of the aforementioned songs, plus a little Robbie Basho thrown in too.

Ex. 6

Listen

Superficially, this final approach to slowness might seem radically different from all the previous examples, but in fact, incorporating this exercise into your regular practice routine can make everything you play, slow or fast, take on new levels of meaning and purpose.

Now many of you might think this technique is little more than new-age hokum, and I can appreciate that. Still, there is no agenda here other than to help you become a more thoughtful and musical player, so I entreat you to give this next exercise a few tries to see if it enhances your playing. If not, you have the six previous examples to work with. But if it does, it could change your playing forever. (Note: I have only reluctantly included an audio version of this exercise because I feel it does not translate well to any recorded audio medium. The true test is the sound you yourself create. If you do use my audio as a guide, please listen with headphones.)

Rather than attempting to explain—acoustically, mentally, and physics-wise—what is going on when you perform this exercise, I urge you to simply follow the instructions below. After experiencing the sounds, you can decide if you've begun listening and hearing differently. (Note: This exercise is best done with an acoustic guitar or with an electric through a relatively clean, low-volume amplifier, otherwise you might be sustaining and resting for much, much longer than you want to.)

1) Find a relatively quiet room in which to do this exercise.

2) With your eyes closed, pick one note.

3) Let it sustain as long as it will naturally, with no vibrato.

4) When the note has decayed fully, take your hand off the guitar and rest for approximately the same amount of time that the note sustained.

5) Repeat this exercise, at least three more times, with any notes you choose.

6) Evaluate the process.

What did you hear? If you're like many players I've done this exercise (Ex. 7) with, you may have noticed more than you would have imagined. For instance, you can actually hear the overtones. Overtones are another topic beyond this scope of this lesson, but the briefest of explanations is to say that there are no "pure" notes in music. Every note is made up of several discrete frequencies, the fundamental (the name we give the note) and many overtones (additional frequencies greater than the fundamental), which usually go undetected if one doesn't play slowly. By playing at this glacial pace, one can hear notes within notes.

Your instrument sustains for much longer than you thought possible.

Different attacks create tones. Did the exercise encourage you to modify your attack? Perhaps you tried using your bare fingers instead of the pick? Did you find yourself picking harder or lighter? Did you pick in different areas relative to the acoustic's soundhole or the electric's bridge?

Resting between notes makes each subsequent note sound fuller.

The lower the note, the longer the sustain.

Does noticing these small details make you a better player? That is not for me to say unequivocally, but certainly this exercise in active listening allows one to recognize the strongest aspects of one's playing and to rectify the weaker aspects. It also can give musicians a greater appreciation of numerous facets of sound, from sound waves and frequency vibrations to one's own auditory perception. If this exercise and these topics are of interest to you, I suggest following up with an investigation of the works of John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and La Monte Young, as they have all worked seriously within the realms of silence, long sustained notes, and what Oliveros calls "Deep Listening."

Less is More, When There’s More

As so often is the case, balance is crucial. Musical choices don't have to be autocratic, dogmatic, or absolute. Slow playing is highly effective when it's offset by its counterpoint—speed. While practicing, if you forgo automatic pilot and remember to equalize a barrage of notes with rests, or long, sustained notes, or pithy, quarter-note phrases (as opposed to 32nd-note run-on sentences), when it comes time to perform, your playing will be invigorated by complementary and dynamic ideas. And, paradoxically, playing slower will make your fast playing seem even faster.