Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

• Learn to phrase like a vocalist.

• Understand the basics of bottleneck slide guitar.

• Develop flowing, singing blues licks.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

One of the most ominous words in the guitar lexicon is “feel.” It’s a word that’s thrown around liberally, yet it’s really impossible to prove or disprove someone’s “feel” because the term is so subjective.

Over the years, it seems to have split the guitar-playing nation into two camps, the shredders and the slow-feel players. Now, we could talk for hours and hours on what this mystical word means and we’d be no closer to an answer, but I do find it insulting to say that a player like Yngwie Malmsteen has no feel when the man plays with fiery passion and excitement—just listen to that vibrato! I’m certain Yngwie deeply feels every note he plays.

When it comes down to what music touches us as humans, we have to ponder a few questions: Does it make you want to sit and cry? Does it make you want to jump up and run around the room like a lunatic? When you pick up your guitar do you want your phrasing to sound robotic, almost sci-fi? Or greasy and gritty? Majestic? Nasty? Peaceful? Manic?

No matter what the intention is, the only real limitation is your ability to put that feeling across with those strings. And the notes aren’t enough—it’s about the attack, the dynamics, the vibrato, and the phrasing.

In my opinion, the guitar’s limitation is its frets. I know they help tremendously with chords, but when you compare the guitar to an instrument like the voice, you realize that we’re severely restricted when it comes to melodic expression. The human voice is capable of the sweetest vibrato. It can bend notes sharp, slide in and out of them, and, of course, create sounds between them. For the longest time I’ve wanted to imitate the human voice on the guitar, and the way to do this, I ultimately discovered, was slide guitar.

Okay, I didn’t grow up in the Mississippi Delta. I’m from a very small town in England and I was born in the late ’80s, so I wasn’t exposed to the music of Robert Johnson or Elmore James. I wasn’t raised on the Allman Brothers or even George Harrison. I do remember one of my first experiences with slide guitar was listening to the incredible Brett Garsed’s Big Sky, and when the track “Drowning” came on, I knew that somehow it just felt good. When I found out he was using a slide I became obsessed and had to look back at all the greats, from Muddy Waters and Duane Allman, to newer players like Derek Trucks and Allen Hinds. Before long, I had guitars dedicated to slide. I even thought I’d try my hand at fretless to see if I could do something similar there.

Below are links to videos of several incredible slide players for you to check out. Have a listen and try to describe what you hear. Focus on the idea that these players try to play something they might sing. This list could go on for pages, so I encourage you to go and do your own research.

Brett Garsed – "Drowning"

Derek Trucks – "Midnight in Harlem" (solo)

Sonny Landreth – "Next to Kindred Spirit"

Anyway, onto actually playing slide.

Here’s the basic idea: A slide is a hard object that, when placed against a string, acts like a fret, only it’s one we can move. Slides can be made of anything from old medicine bottles, wine bottlenecks (this is why some people refer to slide as bottleneck guitar), glazed ceramic, brass, spoons, and microphone stands. Danny Gatton sometimes even used his half-filled beer bottle! Each slide will give you a slightly different tone. For example, a ceramic slide tents to sound a lot warmer than a brass slide. Personally, I opt for a thick Pyrex slide that’s quite loose on my finger. Head on down to your guitar store and try a few out before settling.

The next issue is to decide which finger wears the slide. Many traditional players put the slide on the little finger, while some prefer the ring finger. Some even wear it on their middle finger. I learned to play slide with it on my ring finger, as that felt natural to me, but then taught myself to play with it on my middle finger, like Garsed. This allowed me to fret notes after the slide with two other fingers and angle the slide when playing in standard tuning. Each finger has its own benefits and special techniques, but everything presented in this lesson will be standard stuff, so any finger will do.

But I will say this: Whatever fingers are behind the slide (between the slide and the nut) should lightly rest on the strings to stop any sympathetic vibrations and overtones.

I’m also playing fingerstyle here, which allows me to mute unwanted strings more effectively and get a warmer tone. As a rule, my picking-hand thumb will mute strings below the one I’m playing, and my middle, ring, and little fingers will mute the higher strings while I pluck with my index finger. Many traditional slide players play in an open tuning, so ringing strings usually don’t sound wrong. I’ve opted to do all of these licks in standard tuning like Garsed or Hinds, because I want to be able to play slide when I’m inspired, not when I’m in the right tuning. Muting is key to this approach!

It’s also worth mentioning the Derek Trucks raking technique that I do to give notes a little more bite. The idea is to rake the lower strings with the thumb before plucking the intended note. This gives you a percussive attack and adds to the overall experience.

I’m playing all the audio examples on Macy, my Brent Mason-inspired Suhr. To make slide a little easier, I’ve brought the action up a little more than you’d expect to find on a stock guitar, but it’s not so high that I can’t play standard guitar with minimal effort.

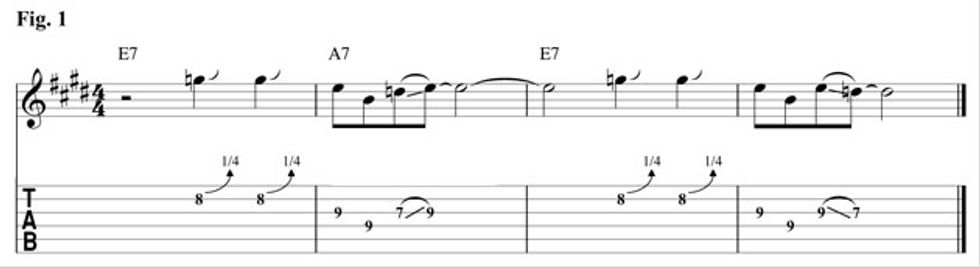

Our first example (Fig. 1) sits nicely around the fourth minor pentatonic box pattern in the key of E major. I’m raking up and sliding into the b3 but using the slide to gradually push that note sharp—it has a great bluesy effect.

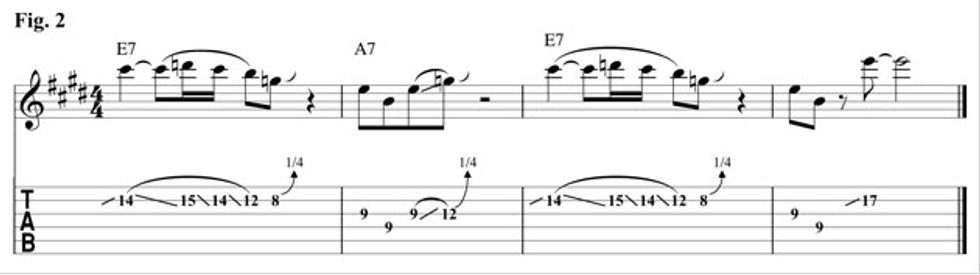

Fig. 2 highlights the more horizontal way of playing slide, as I’m jumping up to the 4th fret on the 2nd string, going up to D, down to B, and then shifting down to hit our bluesy b3 again. On the repeat I jump up to the root, again on the 2nd string. A simple phrase like this has covered a whopping 10 frets!

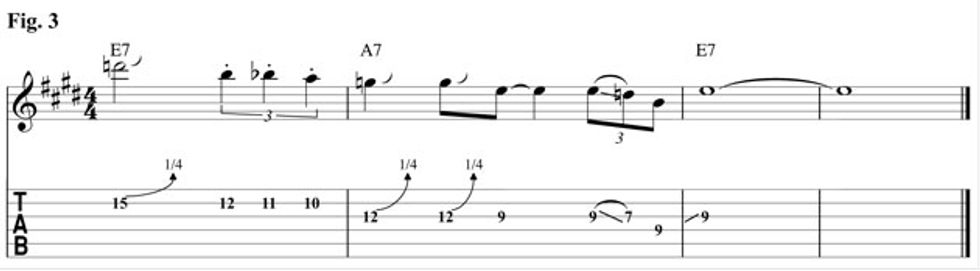

Fig. 3 is another bluesy number based on the E blues scale (E–G–A–Bb–B–D). Listen for the slide into the first note, which is actually below its intended pitch. It’s then slowly brought to pitch and pushed sharp before moving down the blues scale.

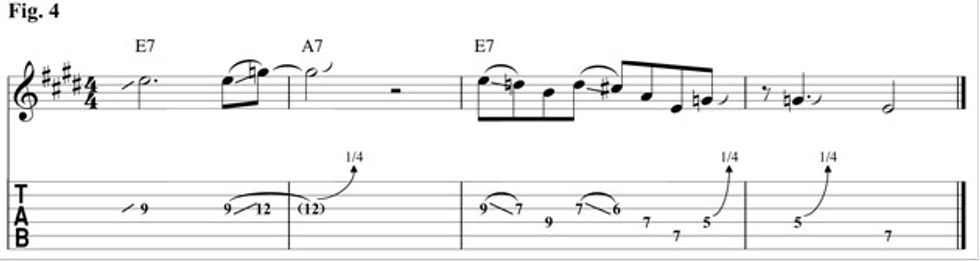

We have a slightly more fiddly idea in Fig. 4. Here, we move across the neck, instead of following a more horizontal path. In the third measure we’re highlighting the problem of standard tuning, as you need to slide from E to D on the 3rd string and then pick the B on the 4th string. In order to do this you need to mute the 3rd string before sliding up to the 9th fret and not allow these notes to bleed into each other. Something like this will work better in an open tuning, but as I said earlier, standard tuning doesn’t require you to relearn the entire neck.

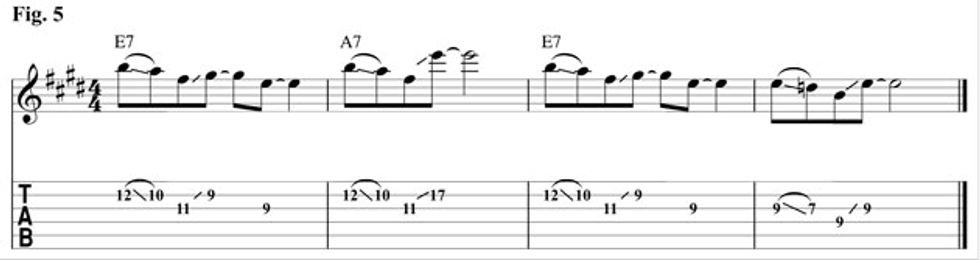

Our last lick (Fig. 5) is a little more demanding as it involves sliding down on one string and then following that with a slide up into a note on an adjacent string. This is where you can really see if your string muting is up to par. It can be a bit difficult at first, but I’m sure you’ll agree, the end result is worth the effort.

And finally, here’s the backing track for the lesson—a simple blues in E.

I hope you’ve got something out of these licks, but if you’re not interested in learning slide, remember, you don’t have to. Look at a player like Jeff Beck who is famous for imitating slide guitar with his whammy bar. You could replicate these ideas with careful bending, whammy-bar tricks, or even on a fretless guitar. The entire concept here is to use the guitar to generate vocal-like sounds. If you can come up with your own way of imitating these ideas, that’s probably even better for you in the long run. Anyone who’s seen Michael Lee Firkins’ instructional video will know exactly what I mean!